A polycube is a solid figure formed by joining one or more equal cubes face to face. Polycubes are the three-dimensional analogues of the planar polyominoes. The Soma cube, the Bedlam cube, the Diabolical cube, the Slothouber–Graatsma puzzle, and the Conway puzzle are examples of packing problems based on polycubes.[1]

Enumerating polycubes

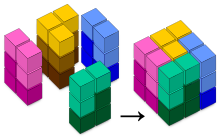

editLike polyominoes, polycubes can be enumerated in two ways, depending on whether chiral pairs of polycubes (those equivalent by mirror reflection, but not by using only translations and rotations) are counted as one polycube or two. For example, 6 tetracubes are achiral and one is chiral, giving a count of 7 or 8 tetracubes respectively.[2] Unlike polyominoes, polycubes are usually counted with mirror pairs distinguished, because one cannot turn a polycube over to reflect it as one can a polyomino given three dimensions. In particular, the Soma cube uses both forms of the chiral tetracube.

Polycubes are classified according to how many cubical cells they have:[3]

| n | Name of n-polycube | Number of one-sided n-polycubes (reflections counted as distinct) (sequence A000162 in the OEIS) |

Number of free n-polycubes (reflections counted together) (sequence A038119 in the OEIS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | monocube | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | dicube | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | tricube | 2 | 2 |

| 4 | tetracube | 8 | 7 |

| 5 | pentacube | 29 | 23 |

| 6 | hexacube | 166 | 112 |

| 7 | heptacube | 1023 | 607 |

| 8 | octacube | 6922 | 3811 |

Fixed polycubes (both reflections and rotations counted as distinct (sequence A001931 in the OEIS)), one-sided polycubes, and free polycubes have been enumerated up to n=22. More recently, specific families of polycubes have been investigated.[4][5]

Symmetries of polycubes

editAs with polyominoes, polycubes may be classified according to how many symmetries they have. Polycube symmetries (conjugacy classes of subgroups of the achiral octahedral group) were first enumerated by W. F. Lunnon in 1972. Most polycubes are asymmetric, but many have more complex symmetry groups, all the way up to the full symmetry group of the cube with 48 elements. There are 33 different symmetry types that a polycube can have (including asymmetry).[2]

Properties of pentacubes

edit12 pentacubes are flat and correspond to the pentominoes. 5 of the remaining 17 have mirror symmetry, and the other 12 form 6 chiral pairs.

The bounding boxes of the pentacubes have sizes 5×1×1, 4×2×1, 3×3×1, 3×2×1, 3×2×2, and 2×2×2.[6]

A polycube may have up to 24 orientations in the cubic lattice, or 48, if reflection is allowed. Of the pentacubes, 2 flats (5-1-1 and the cross) have mirror symmetry in all three axes; these have only three orientations. 10 have one mirror symmetry; these have 12 orientations. Each of the remaining 17 pentacubes has 24 orientations.

Octacube and hypercube unfoldings

editThe tesseract (four-dimensional hypercube) has eight cubes as its facets, and just as the cube can be unfolded into a hexomino, the tesseract can be unfolded into an octacube. One unfolding, in particular, mimics the well-known unfolding of a cube into a Latin cross: it consists of four cubes stacked one on top of each other, with another four cubes attached to the exposed square faces of the second-from-top cube of the stack, to form a three-dimensional double cross shape. Salvador Dalí used this shape in his 1954 painting Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus)[7] and it is described in Robert A. Heinlein's 1940 short story "And He Built a Crooked House".[8] In honor of Dalí, this octacube has been called the Dalí cross.[9][10] It can tile space.[9]

More generally (answering a question posed by Martin Gardner in 1966), out of all 3811 different free octacubes, 261 are unfoldings of the tesseract.[9][11]

Boundary connectivity

editAlthough the cubes of a polycube are required to be connected square-to-square, the squares of its boundary are not required to be connected edge-to-edge. For instance, the 26-cube formed by making a 3×3×3 grid of cubes and then removing the center cube is a valid polycube, in which the boundary of the interior void is not connected to the exterior boundary. It is also not required that the boundary of a polycube form a manifold. For instance, one of the pentacubes has two cubes that meet edge-to-edge, so that the edge between them is the side of four boundary squares.

If a polycube has the additional property that its complement (the set of integer cubes that do not belong to the polycube) is connected by paths of cubes meeting square-to-square, then the boundary squares of the polycube are necessarily also connected by paths of squares meeting edge-to-edge.[12] That is, in this case the boundary forms a polyominoid.

Every k-cube with k < 7 as well as the Dalí cross (with k = 8) can be unfolded to a polyomino that tiles the plane. It is an open problem whether every polycube with a connected boundary can be unfolded to a polyomino, or whether this can always be done with the additional condition that the polyomino tiles the plane.[10]

Dual graph

editThe structure of a polycube can be visualized by means of a "dual graph" that has a vertex for each cube and an edge for each two cubes that share a square.[13] This is different from the similarly-named notions of a dual polyhedron, and of the dual graph of a surface-embedded graph.

Dual graphs have also been used to define and study special subclasses of the polycubes, such as the ones whose dual graph is a tree.[14]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Polycube." From MathWorld

- ^ a b Lunnon, W. F. (1972), "Symmetry of Cubical and General Polyominoes", in Read, Ronald C. (ed.), Graph Theory and Computing, New York: Academic Press, pp. 101–108, ISBN 978-1-48325-512-5

- ^ Polycubes, at The Poly Pages

- ^ "Enumeration of Specific Classes of Polycubes", Jean-Marc Champarnaud et al, Université de Rouen, France PDF

- ^ "Dirichlet convolution and enumeration of pyramid polycubes", C. Carré, N. Debroux, M. Deneufchâtel, J. Dubernard, C. Hillairet, J. Luque, O. Mallet; November 19, 2013 PDF

- ^ Aarts, Ronald M. "Pentacube". From MathWorld.

- ^ Kemp, Martin (1 January 1998), "Dali's dimensions", Nature, 391 (27): 27, Bibcode:1998Natur.391...27K, doi:10.1038/34063

- ^ Fowler, David (2010), "Mathematics in Science Fiction: Mathematics as Science Fiction", World Literature Today, 84 (3): 48–52, doi:10.1353/wlt.2010.0188, JSTOR 27871086, S2CID 115769478,

Robert Heinlein's "And He Built a Crooked House," published in 1940, and Martin Gardner's "The No-Sided Professor," published in 1946, are among the first in science fiction to introduce readers to the Moebius band, the Klein bottle, and the hypercube (tesseract).

. - ^ a b c Diaz, Giovanna; O'Rourke, Joseph (2015), Hypercube unfoldings that tile and , arXiv:1512.02086, Bibcode:2015arXiv151202086D.

- ^ a b Langerman, Stefan; Winslow, Andrew (2016), "Polycube unfoldings satisfying Conway's criterion" (PDF), 19th Japan Conference on Discrete and Computational Geometry, Graphs, and Games (JCDCG^3 2016).

- ^ Turney, Peter (1984), "Unfolding the tesseract", Journal of Recreational Mathematics, 17 (1): 1–16, MR 0765344.

- ^ Bagchi, Amitabha; Bhargava, Ankur; Chaudhary, Amitabh; Eppstein, David; Scheideler, Christian (2006), "The effect of faults on network expansion", Theory of Computing Systems, 39 (6): 903–928, arXiv:cs/0404029, doi:10.1007/s00224-006-1349-0, MR 2279081, S2CID 9332443. See in particular Lemma 3.9, p. 924, which states a generalization of this boundary connectivity property to higher-dimensional polycubes.

- ^ Barequet, Ronnie; Barequet, Gill; Rote, Günter (2010), "Formulae and growth rates of high-dimensional polycubes", Combinatorica, 30 (3): 257–275, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.217.7661, doi:10.1007/s00493-010-2448-8, MR 2728490, S2CID 18571788.

- ^ Aloupis, Greg; Bose, Prosenjit K.; Collette, Sébastien; Demaine, Erik D.; Demaine, Martin L.; Douïeb, Karim; Dujmović, Vida; Iacono, John; Langerman, Stefan; Morin, Pat (2011), "Common unfoldings of polyominoes and polycubes", Computational geometry, graphs and applications (PDF), Lecture Notes in Comput. Sci., vol. 7033, Springer, Heidelberg, pp. 44–54, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-24983-9_5, hdl:1721.1/73836, MR 2927309.

External links

edit- Wooden hexacube puzzle by Kadon

- Polycube Symmetries

- Polycube solver Program (with Lua source code) to fill boxes with polycubes using Algorithm X.

- Kevin Gong's enumeration of polycubes