Pendleton is a city in and the county seat[6] of Umatilla County, Oregon, United States. The population was 17,107 at the time of the 2020 census, which includes approximately 1,600 people who are incarcerated at Eastern Oregon Correctional Institution.[7]

Pendleton, Oregon | |

|---|---|

Downtown Pendleton | |

| Motto: The Real West | |

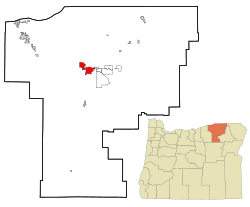

Location of Pendleton in Umatilla County, Oregon (left) and of Umatilla County in Oregon (right) | |

| Coordinates: 45°40′32″N 118°49′11″W / 45.67556°N 118.81972°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Oregon |

| County | Umatilla |

| Incorporated | 1880 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | John Turner[1] |

| Area | |

• Total | 11.51 sq mi (29.81 km2) |

| • Land | 11.51 sq mi (29.81 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 1,099 ft (335 m) |

| Population | |

• Total | 17,107 |

| • Density | 1,486.27/sq mi (573.85/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (Pacific) |

| ZIP Code | 97801 |

| Area code(s) | 458 and 541 |

| FIPS code | 41-57150[5] |

| GNIS feature ID | 2411399[3] |

| Website | www.pendleton.or.us |

Pendleton is the smaller of the two principal cities of the Hermiston–Pendleton Micropolitan Statistical Area. This micropolitan area covers Morrow and Umatilla counties[8] and had a combined population of 92,261 at the 2020 census.[5]

History

editA European-American commercial center began to develop here in 1851, when William C. McKay established a trading post at the mouth of McKay Creek. A United States Post Office named Marshall (for the owner, and sometime gambler, of another local store) was established April 21, 1865, and later renamed Pendleton, after politician and diplomat George H. Pendleton (1825–1889), who served as a U.S. Representative and Senator from Ohio.[9] The city was incorporated by the Oregon Legislative Assembly on October 25, 1880.[10]

By 1900, Pendleton had a population of 4,406 and was the fourth-largest city in Oregon. The Pendleton Woolen Mills and Pendleton Round Up became features of the city captured in early paintings by Walter S. Bowman. Like many cities in Eastern Oregon, where thousands of Chinese immigrant workers built the transcontinental railroad, it had a flourishing Chinatown that developed as the workers settled here. The sector is supposed to have been underlain by a network of tunnels, which are now a tourist attraction. The authenticity as a Chinese tunnel system has been questioned.[11]

The town is the cultural center of Eastern Oregon.[12] Pendleton's "Old town" is listed as a Historic District on the National Register of Historic Places.[13]

The Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation (CTUIR) have their property nearby. They have established the Wildhorse Resort & Casino and golf course on the reservation to generate revenue for development and welfare. They have also built the Tamástslikt Cultural Institute, for education and interpretation of their cultures.[12]

Economy

editPendleton Woolen Mills is a maker of wool blankets, shirts, and an assortment of other woolen goods. Founded in 1909 by Clarence, Roy and Chauncey Bishop, the company built upon earlier businesses related to the many sheep ranches in the region. A wool-scouring plant opened in Pendleton in 1893 to wash raw wool for shipping. In 1895, the scouring mill was converted into a mill that made wool blankets and robes for Native Americans. Both businesses failed to survive, but the Bishops, with the help of a local bond issue, enlarged the mill and improved its efficiency. They developed a successful line of garments and blankets with "vivid colors and intricate patterns."[14]

St. Anthony Hospital in Pendleton is a 25-bed medical center.[15]

Eastern Oregon Correctional Institution (EOCI) in Pendleton is the only place in Oregon where inmates make "Prison Blues" denim clothing. The prison also operates a commercial laundry serving customers that include EOCI, the Snake River Correctional Institution, Pendleton High School, a local flour mill, and other entities. In addition, some EOCI inmates work as clerks or have jobs in food service or maintenance.[16]

Geography and climate

editAccording to the U.S. Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 10.52 square miles (27.25 km2), all land.[17]

The city was built on both sides of the Umatilla River, which has periodically flooded and caused some damage. In the beginning, the river was vital as a transportation and trading route for settlers, as well as a water and power source. It connected the city to the Columbia River.

Pendleton has a semi-arid climate (Köppen BSk) with short, cool winters and hot summers. Pendleton had the highest temperature recorded in Oregon at 119 °F (48 °C) on August 10, 1898,[18] which was later tied on June 29, 2021, at the Pelton Dam COOP weather station in Jefferson County, Oregon, and the Moody Farms Agrimet weather station in Wasco County, Oregon.[19] The highest temperature recorded in Pendleton in recent times was 117 °F (47 °C) on June 29, 2021.

| Climate data for Pendleton, Oregon (Eastern Oregon Regional Airport), 1991–2020 normals,[a] extremes 1892–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 71 (22) |

76 (24) |

83 (28) |

95 (35) |

103 (39) |

117 (47) |

114 (46) |

119 (48) |

104 (40) |

93 (34) |

80 (27) |

75 (24) |

119 (48) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 60.7 (15.9) |

61.6 (16.4) |

69.4 (20.8) |

77.4 (25.2) |

88.0 (31.1) |

95.2 (35.1) |

102.6 (39.2) |

101.0 (38.3) |

92.6 (33.7) |

80.0 (26.7) |

66.5 (19.2) |

59.9 (15.5) |

104.2 (40.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 41.7 (5.4) |

46.4 (8.0) |

55.0 (12.8) |

61.8 (16.6) |

70.9 (21.6) |

78.4 (25.8) |

89.2 (31.8) |

87.6 (30.9) |

78.0 (25.6) |

63.5 (17.5) |

49.1 (9.5) |

40.8 (4.9) |

63.5 (17.5) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 34.9 (1.6) |

38.0 (3.3) |

44.4 (6.9) |

50.1 (10.1) |

57.9 (14.4) |

64.6 (18.1) |

73.0 (22.8) |

71.8 (22.1) |

63.5 (17.5) |

51.5 (10.8) |

40.7 (4.8) |

34.2 (1.2) |

52.1 (11.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 28.0 (−2.2) |

29.6 (−1.3) |

33.7 (0.9) |

38.3 (3.5) |

45.0 (7.2) |

50.7 (10.4) |

56.7 (13.7) |

56.0 (13.3) |

49.0 (9.4) |

39.4 (4.1) |

32.3 (0.2) |

27.5 (−2.5) |

40.5 (4.7) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 11.7 (−11.3) |

15.8 (−9.0) |

23.1 (−4.9) |

28.5 (−1.9) |

33.5 (0.8) |

41.2 (5.1) |

47.2 (8.4) |

46.0 (7.8) |

37.8 (3.2) |

25.7 (−3.5) |

18.8 (−7.3) |

12.1 (−11.1) |

3.7 (−15.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −26 (−32) |

−21 (−29) |

1 (−17) |

17 (−8) |

22 (−6) |

30 (−1) |

38 (3) |

30 (−1) |

21 (−6) |

11 (−12) |

−13 (−25) |

−28 (−33) |

−28 (−33) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.52 (39) |

1.19 (30) |

1.33 (34) |

1.21 (31) |

1.45 (37) |

1.05 (27) |

0.26 (6.6) |

0.31 (7.9) |

0.53 (13) |

1.09 (28) |

1.39 (35) |

1.50 (38) |

12.83 (326.5) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 3.8 (9.7) |

4.5 (11) |

0.7 (1.8) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

1.2 (3.0) |

5.4 (14) |

15.7 (39.75) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 12.3 | 9.9 | 11.6 | 9.6 | 9.6 | 6.5 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 3.8 | 8.2 | 11.6 | 12.5 | 100.2 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 2.9 | 2.2 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.2 | 3.7 | 11.2 |

| Source 1: NOAA[20] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: National Weather Service[21] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 243 | — | |

| 1880 | 730 | 200.4% | |

| 1890 | 2,506 | 243.3% | |

| 1900 | 4,406 | 75.8% | |

| 1910 | 4,460 | 1.2% | |

| 1920 | 6,837 | 53.3% | |

| 1930 | 6,621 | −3.2% | |

| 1940 | 8,847 | 33.6% | |

| 1950 | 11,774 | 33.1% | |

| 1960 | 14,434 | 22.6% | |

| 1970 | 13,197 | −8.6% | |

| 1980 | 14,521 | 10.0% | |

| 1990 | 15,126 | 4.2% | |

| 2000 | 16,354 | 8.1% | |

| 2010 | 16,612 | 1.6% | |

| 2020 | 17,107 | 3.0% | |

| source:[5][22][4] | |||

As of 2000 the median income for a household in the city was $36,800, and the median income for a family was $47,410. Males had a median income of $31,763 versus $23,858 for females. The per capita income for the city was $17,551. About 8.7% of families and 13.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 16.4% of those under age 18 and 8.1% of those age 65 or over.[5]

2010 census

editAs of the census of 2010, there were 16,612 people, 6,220 households, and 3,789 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,579.1 inhabitants per square mile (609.7/km2). There were 6,800 housing units at an average density of 646.4 per square mile (249.6/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 87.3% White, 1.4% African American, 3.2% Native American, 1.1% Asian, 0.2% Pacific Islander, 3.6% from other races, and 3.3% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 9.7% of the population.[5]

There were 6,220 households, of which 30.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 42.9% were married couples living together, 12.6% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.5% had a male householder with no wife present, and 39.1% were non-families. 31.3% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.37 and the average family size was 2.96.[5]

The median age in the city was 36.9 years. 21.9% of residents were under the age of 18; 11.1% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 28% were from 25 to 44; 26.3% were from 45 to 64; and 12.8% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 53.4% male and 46.6% female.[5]

Arts and culture

editAnnual events

editIn addition to the woolen mills, Pendleton is also famous for its annual rodeo, the Pendleton Round-Up.[23][24][25] First held in 1910, it is part of the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association (PRCA)-sanctioned rodeo circuit.[26] It is among the top ten PRCA venues in terms of prize money.[26]

Pendleton is also home to the annual Pendleton Whiskey Music Festival [1]. This annual event is held in the historic Pendleton Round-up Arena in July. Past performers have included Maroon 5, Toby Keith, Zac Brown Band, Pitbull, Blake Shelton, and Post Malone.

The Festival of Trees is held in early December each year. It is a fundraising event produced by the St. Anthony Hospital Foundation.[27]

Museums and other points of interest

editLocal arts institutions include the Pendleton Center for the Arts (in the town's old Carnegie Library building)[28] and Crow's Shadow Institute of the Arts on the nearby Umatilla Indian Reservation.[29]

The Heritage Station Museum operated by the Umatilla County Historical Society is located in the historic 1909 Pendleton Train Depot. The museum offers two galleries covering regional and local history as well as a one-room schoolhouse, family cabin, caboose, barn, and signal house.[30]

The Pendleton Farmers' Market operates on Friday evenings from May through October on South Main Street.[31]

Pendleton Underground Tours features the history of Pendleton and a tour through the tunnels and the brothels. It is open year-round.[32]

Sports and recreation

editThe city hosts the annual Oregon School Activities Association 2A basketball tournament at the Pendleton Convention Center. Eight teams of boys and eight of girls compete for their respective championships during a four-day tournament. Civic leaders regard the influx of family and other fans the second-most important boost to the local economy, behind the Round-Up. Total attendance at the tournament in 2010 exceeded 13,000.[33]

The Pendleton Aquatic Center, managed by Pendleton Parks & Recreation, features two tower water slides as well tubes and smaller slides, three pools, a diving well, and picnic areas. The aquatic center is adjacent to the high school.[34]

Transportation

editHighways serving Pendleton include Interstate 84 and U.S. Route 30 running east–west and U.S. Route 395 running north–south. The city is also served by Oregon Route 37 and Oregon Route 11.[35]

Pendleton lies along the Union Pacific Railroad (UP), constructed originally through the area in the 1880s by the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company (OR&N). In 1880, the OR&N began construction of a rail line from Portland through the Columbia Gorge to eastern Oregon. It reached Umatilla and Wallula in 1881, Pendleton in 1882, and then La Grande, Baker City, and Huntington, where by 1884 it met the UP line from Utah. Since Pendleton was also connected by rail to the Northern Pacific line at Wallula and Walla Walla, by 1885 it was a stop on two transcontinental lines. The UP absorbed the OR&N line in 1889.[36]

Between 1977 and 1997, the city was a regular stop along the former route of Amtrak's Pioneer between Chicago and Seattle via Salt Lake City and Portland.[37]

Regional public aviation service is through Eastern Oregon Regional Airport, 3 miles (5 km) outside Pendleton. The airport is owned by the City of Pendleton.[38] Boutique Air offers daily flights between Pendleton and Portland, which began in 2016.[39]

Media

editTwo newspapers are published in Pendleton. The East Oregonian is a daily with a circulation of about 6,800. The Pendleton Record is a weekly with a circulation of about 900.[40]

KFFX-TV (Fox 11), a television station based in Pendleton, serves a market that also includes the Washington cities of Yakima, Pasco, Richland, and Kennewick.[41] Oregon radio stations based in or near Pendleton include: KTIX (1240 AM); KUMA (1290 AM); OPB station KRBM (90.9 FM); KLKY (96.1 FM) with translator K237DS (95.3 FM); KNHK-FM (101.9) with translator K262CJ (100.3 FM); KWHT (103.5 FM); and KWVN-FM (107.7).[42]

Notable people

edit- Tracy Baker – Major League Baseball player; born in Pendleton[43]

- Walter S. Bowman, professional photographer; based in Pendleton from the late 1880s to mid-1930s[44]

- John Bunnell – hosted World's Wildest Police Videos; born in Pendleton[45]

- Dave Cockrum – comic book artist; born in Pendleton[46]

- Dave Kingman – Major League Baseball player, three-time All-Star; born in Pendleton[47]

- Michael J. Kopetski – former representative for Oregon's 5th congressional district; born in Pendleton[48]

- James Lavadour – painter; lifelong resident of Umatilla Reservation[49]

- Bob Lilly – Pro Football Hall of Fame defensive tackle; graduated from Pendleton High School in 1957[50]

- Donald McKay – scout and leader of the Warm Springs Indians during the Modoc War

- William Cameron McKay, Oregon pioneer physician, scout

- Elaine Miles – actress who played Marilyn Whirlwind on Northern Exposure; early childhood on Umatilla Reservation[51]

- Frances Moore Lappé – author and activist; born in Pendleton[52]

- Lee Moorhouse - Indian agent in Pendleton and amateur photographer

- Charles Sams - Director of the National Park Service; native of Pendleton[53]

- Roy Schuening – football player, Oregon State and NFL; born in Pendleton[54]

- Gordon Smith – 1997–2009 U.S. Senator (R) from Oregon, born in Pendleton[55]

- Milan Smith – judge on United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit; born in Pendleton[56]

- Kenneth Snelson – sculptor and photographer; childhood in Pendleton[57]

- Dan Straily – Major League Baseball player; grew up in Pendleton[58]

- Archie R. Twitchell - test pilot and actor [59]

- Quade Winter, opera singer

Sister cities

editPendleton has a sister city relationship with Marikina, a municipality-turned-city in the Philippines. The relationship was established in 1971 when then mayor Eddie O. Knopp and Marikina mayor Osmundo de Guzman had their daughters temporarily switch schools in their respective towns. By 1974, Knopp visited Marikina after Philippine president Ferdinand Marcos declared a nationwide martial law two years prior, and expressed that based on the "excellent peace and order situation" he saw while in the country, the United States could try implementing martial law in towns rampant with violence and crime.[60]

Another sister city of Pendleton is the town of Minamisōma, in Fukushima Prefecture, Japan. Minamisoma is 16 miles (26 km) north of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, which was damaged by the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami. Since then, Japanese exchange students from Minamisoma have continued to visit Pendleton, though students from Pendleton have stopped visiting Minamisoma over growing radiation concerns.[61]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the highest and lowest temperature readings during an entire month or year) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.

- ^ "Mayor John Turner". Retrieved May 5, 2017.

- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Pendleton, Oregon

- ^ a b "Census Population API". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 28, 2014.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ "QuickFacts Pendleton city, Oregon". census.gov. Retrieved November 10, 2021.

- ^ "Counties in Micropolitan Statistical Areas". Bureau of Economic Analysis, U.S. Department of Commerce. November 21, 2013. Archived from the original on July 27, 2018. Retrieved August 27, 2014.

- ^ "History of Pendleton". The City of Pendleton. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- ^ Leeds, W. H. (1899). "Special Laws". The State of Oregon General and Special Laws and Joint Resolutions and Memorials Enacted and Adopted by the Twentieth Regular Session of the Legislative Assembly. Salem, Oregon: State Printer: 747.

- ^ Wegars, Priscilla. "Asian American Comparative Collection: Asian American Sites and Museum Exhibits in the Pacific Northwest, Great Basin, and Canada". University of Idaho. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

Pendleton – Pendleton Underground. An interesting tour of downtown Pendleton basements. However, some guides call them "Chinese tunnels" thus perpetuating a stereotype for which there is no basis in fact. See "Ongoing Research" for a discussion of so-called "Chinese tunnels."

- ^ a b Scanlan, John. "Pendleton". The Oregon Encyclopedia. Portland State University and the Oregon Historical Society. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- ^ Sargent, Gail (James Lynch & Associates) (October 10, 1986). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: South Main Street Commercial Historic District" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved August 29, 2014.

- ^ "Company History". Pendleton Woolen Mills. 2014. Retrieved August 27, 2014.

- ^ "St. Anthony Hospital". U.S. News & World Report (Best Hospitals). 2014. Retrieved August 27, 2014.

- ^ "Eastern Oregon Correctional Institution". Oregon Department of Corrections. Retrieved June 6, 2014.

- ^ "State and County Quick Facts". United States Census Bureau. July 8, 2014. Archived from the original on August 24, 2014. Retrieved August 27, 2014.

- ^ "Record highest temperatures by state" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. December 2003. Retrieved June 23, 2011.

- ^ Loikith, Paul (April 20, 2023). "The 2021 Pacific Northwest Heatwave (Heat Dome)". Oregon Encyclopedia. Oregon Historical Society. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Pendleton, OR". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "NOAA Online Weather Data – NWS Pendleton". National Weather Service. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ Moffatt, Riley Moore (1996). Population History of Western U.S. Cities and Towns, 1850–1990. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-8108-3033-2.

- ^ Furlong, Charles Wellington (August 1916). "The Epic Drama of The West". Harper's Monthly Magazine. CXXXIII (795): 368. Retrieved August 16, 2009.

- ^ "History". Pendleton Round-Up. Retrieved August 28, 2014.

- ^ "Pendleton Round-Up". Travel Pendleton. Pendleton Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on September 3, 2014. Retrieved August 28, 2014.

- ^ a b "Pendleton Round-Up". Pro Rodeo Hall of Fame. Retrieved August 29, 2014.

- ^ "CHI St. Anthony Hospital Foundation". St. Anthony Hospital Foundation. 2014. Retrieved August 31, 2014.

- ^ Donovan, Sally (Donovan Associates) (August 15, 1997). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Umatilla County Library" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved August 29, 2014.

- ^ "About Us". Crow's Shadow Institute of the Arts. Retrieved August 29, 2014.

- ^ "Umatilla County Historical Society". Heritage Station Museum.

- ^ "Food for Oregon: Pendleton Farmers' Market". Oregon State University Extension Service. Archived from the original on February 7, 2016. Retrieved August 28, 2014.

- ^ "Pendleton Underground Tours". Pendleton Underground Tours.

- ^ Wright, Phil (March 2, 2011). "Getting Ready for the Party; Pendleton Prepares for Basketball Invasion". East Oregonian. Pendleton. Archived from the original on August 27, 2014. Retrieved August 27, 2014.

- ^ "Cool Fun at the Pool in Pendleton". Pendleton Parks & Recreation. 2014. Retrieved August 27, 2014.

- ^ Oregon Road & Recreation Atlas (5th ed.). Santa Barbara, California: Benchmark Maps. 2012. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-0-929591-62-9.

- ^ Minor, Woodruff (August 31, 2012). "Ordinance 3835 Exhibit E" (PDF). City of Pendleton. Retrieved August 27, 2014.

- ^ "Restore the Pioneer Train!". Pioneer Restoration Organization. 2014. Retrieved August 27, 2014.

- ^ "AirportIQ 5010: Eastern Oregon Regional at Pendleton". GCR, Inc. 2014. Retrieved August 27, 2014.

- ^ Sierra, Antonio (August 15, 2016). "Pendleton drops SeaPort for Boutique Air". eastoregonian.com. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

- ^ "Newspapers Published in Oregon". Oregon Blue Book. Oregon Secretary of State. 2014. Retrieved September 5, 2014.

- ^ "KFFX Channel 11". Station Index. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- ^ "Oregon Radio Stations". Oregon Blue Book. Oregon Secretary of State. 2014. Retrieved September 5, 2014.

- ^ "Tracy Baker". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- ^ "Historical Photograph Collection: The Walter S. Bowman collection, 1890-1925". University of Oregon Libraries. Archived from the original on October 12, 2008. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- ^ "John Bunnell Biography". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- ^ "Dave Cockrum". IMDb. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- ^ "Dave Kingman". MLB Advanced Media. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- ^ "Kopetski, Michael J." Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Office of the Historian. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- ^ Farr, Sheila (September 16, 2005). "Desolation, Transformation: James Lavadour's Landscapes of the Mind". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on October 21, 2012. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- ^ "Biography". BobLilly.com. Archived from the original on March 8, 2016. Retrieved March 13, 2016.

- ^ Taylor, Catherine. "Marilyn Speaks!". Radiance (Fall 1993). Radiance: The Magazine for Large Women. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- ^ "Frances Moore Lappé". Americans Who Tell the Truth. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ^ "Charles F. Sams III". VA News. Retrieved January 7, 2024.

- ^ "Roy Schuening". NFL Enterprises. 2014. Retrieved August 31, 2014.

- ^ "Smith, Gordon Harold, (1952– )". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. U.S. Senate Historical Office. Retrieved August 31, 2014.

- ^ "Smith, Milan Dale Jr". Biographical Directory of Federal Judges. Federal Judicial Center. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ^ "Kenneth Duane Snelson". Black Mountain College Project. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ^ Mazzolini, A. J. (April 4, 2012). "Pitcher Straily Climbs Ladder Towards MLB". East Oregonian. Archived from the original on January 22, 2013. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- ^ "Archie Raymond Twitchell". b-Westerns. Retrieved June 18, 2022.

- ^ Del Rosario, Simeon G. (1974). How Martial Law Saved Democracy in the Philippines. SGR Research and Publishing. p. 28. Retrieved November 12, 2024.

- ^ "Pendleton Weighs Safety of Visits to Sister City". KGW. September 14, 2013. Archived from the original on August 28, 2014. Retrieved August 28, 2014.