Paul Jozef Crutzen (Dutch pronunciation: [pʌul ˈjoːzəf ˈkrʏtsə(n)]; 3 December 1933 – 28 January 2021)[2][3] was a Dutch meteorologist and atmospheric chemist.[4][5][6] In 1995, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry alongside Mario Molina and Frank Sherwood Rowland for their work on atmospheric chemistry and specifically for his efforts in studying the formation and decomposition of atmospheric ozone. In addition to studying the ozone layer and climate change, he popularized the term Anthropocene to describe a proposed new epoch in the Quaternary period when human actions have a drastic effect on the Earth. He was also amongst the first few scientists to introduce the idea of a nuclear winter to describe the potential climatic effects stemming from large-scale atmospheric pollution including smoke from forest fires, industrial exhausts, and other sources like oil fires.

Paul J. Crutzen | |

|---|---|

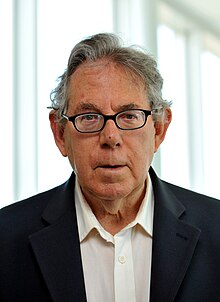

Crutzen in 2010 | |

| Born | Paul Jozef Crutzen 3 December 1933 Amsterdam, Netherlands |

| Died | 28 January 2021 (aged 87) Mainz, Germany |

| Alma mater | University of Stockholm |

| Known for |

|

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | Determination of parameters appearing in the "dry" and the "wet" photochemical theories for ozone in the stratosphere. (1968) |

| Doctoral advisor |

|

| Doctoral students | |

| Website | www |

He was a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and an elected foreign member of the Royal Society in the United Kingdom.[7]

Early life and education

editCrutzen was born in Amsterdam, the son of Anna (Gurk) and Josef Crutzen.[8] In September 1940, the same year Germany invaded The Netherlands, Crutzen entered his first year of elementary school. His classes moved around to different locations after the primary school was taken over by the Germans; during the last months of the war he experienced the 'winter of hunger' with several of his schoolmates dying of famine or disease.[9] In 1946 with some special help he graduated from elementary school and moved onto Hogere Burgerschool (Higher Citizens School). There, with the help of his cosmopolitian parents he became fluent in French, English, and German.[9] Along with languages he also focused on natural sciences in this school, graduating in 1951; however his exam results did not qualify him for university scholarships.[9] Instead, he studied Civil Engineering at a Higher Professional Education school with lower costs, and took a job with the Bridge Construction Bureau in Amsterdam in 1954.[9] After completing military service, in 1958 he married Terttu Soininen, a Finnish university student whom he had met a few years earlier and moved with her to Gävle, a tiny city 200 km north of Stockholm where he took a job at a construction bureau.[9] After seeing an advertisement by the Department of Meteorology at Stockholm University for a computer programmer, he applied, was selected, and in July 1959 moved with his wife and new daughter Ilona to Stockholm.[9]

Beginning of academic career

editIn the 1920's Norwegian meteorologists began using fluid mechanics in analyse weather, and by 1959 the Meteorology Institute of Stockholm University was at the forefront of meteorology research using numerical modeling.[9] The theories were validated in 1960 by images from Tiros, the first weather satellite.

At that time, Stockholm University housed the fastest computers in the world with the BESK (Binary Electronic Sequence Calculator) and its successor, the Facit EDB. Crutzen was involved with the programming and application of some of those early numerical models for weather prediction, and also developed a tropical cyclone model himself.[9]

Working as a programmer at the university, he was able to take other lectures and in 1963 applied for a PhD program with a thesis combining mathematics, statistics and meteorology.[9]

Although intending to extend his cyclone model for his thesis, around 1965 he was asked to help US scientists with a numerical model for the distribution of oxygen allotropes (atomic oxygen, molecular oxygen and ozone) in the stratosphere, the mesosphere and the lower thermosphere. This involved studies of stratospheric chemistry and the photochemistry of ozone. His PhD awarded in 1968, Determination of parameters appearing in the "dry" and the "wet" photochemical theories for ozone in the stratosphere, suggested that nitrogen oxides (NOx) should be studied.[9]

His thesis was well-received and led to a post-doctoral fellowship at the Clarendon Laboratory of the University of Oxford, on behalf of the European Space Research Organisation (ESRO), the precursor of ESA.[9]

Research career

editCrutzen conducted research primarily in atmospheric chemistry.[10][11][12][13][14][15] He is best known for his research on ozone depletion. In 1970[16] he pointed out that emissions of nitrous oxide (N2O), a stable, long-lived gas produced by soil bacteria, from the Earth's surface could affect the amount of nitric oxide (NO) in the stratosphere. Crutzen showed that nitrous oxide lives long enough to reach the stratosphere, where it is converted into NO. Crutzen then noted that increasing use of fertilizers might have led to an increase in nitrous oxide emissions over the natural background, which would in turn result in an increase in the amount of NO in the stratosphere. Thus human activity could affect the stratospheric ozone layer. In the following year, Crutzen and (independently) Harold Johnston suggested that NO emissions from the fleet of, then proposed, supersonic transport (SST) airliners (a few hundred Boeing 2707s), which would fly in the lower stratosphere, could also deplete the ozone layer; however more recent analysis has disputed this as a large concern.[17]

In 1974 Crutzen received a prepublication draft of a scientific paper by Frank S. Rowland, professor of Chemistry at University of California, Irvine, and Mario J. Molina, a postdoctoral fellow from Mexico. It concerned the possible destructive effects of chlorofluoromethanes on the ozone layer. Crutzen immediately developed a model of this effect, which predicted severe depletion of ozone if those chemicals continued to be used at that current rate. [9]

Crutze has listed his main research interests as "Stratospheric and tropospheric chemistry, and their role in the biogeochemical cycles and climate".[18] From 1980, he worked at the Department of Atmospheric Chemistry at the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry,[19] in Mainz, Germany; the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego;[20] and at Seoul National University,[21] South Korea. He was also a long-time adjunct professor at Georgia Institute of Technology and research professor at the department of meteorology at Stockholm University, Sweden.[22] From 1997 to 2002 he was professor of aeronomy at the Department of Physics and Astronomy at Utrecht University.[23]

He co-signed a letter from over 70 Nobel laureate scientists to the Louisiana Legislature supporting the repeal of that U.S. state's creationism law, the Louisiana Science Education Act.[24] In 2003 he was one of 22 Nobel laureates who signed the Humanist Manifesto.[25]

As of 2021[update], Crutzen had an h-index of 151 according to Google Scholar[26] and of 110 according to Scopus.[27] On his death, the president of the Max Planck Society, Martin Stratmann, said that Crutzen's work led to the ban on ozone-depleting chemicals, which was an unprecedented example of Nobel Prize basic research directly leading to a global political decision.[28]

Anthropocene

editOne of Crutzen's research interests was the Anthropocene.[29][30] In 2000, in IGBP Newsletter 41, Crutzen and Eugene F. Stoermer, to emphasize the central role of mankind in geology and ecology, proposed using the term anthropocene for the current geological epoch. In regard to its start, they said:

To assign a more specific date to the onset of the "anthropocene" seems somewhat arbitrary, but we propose the latter part of the 18th century, although we are aware that alternative proposals can be made (some may even want to include the entire holocene). However, we choose this date because, during the past two centuries, the global effects of human activities have become clearly noticeable. This is the period when data retrieved from glacial ice cores show the beginning of a growth in the atmospheric concentrations of several "greenhouse gases", in particular CO2 and CH4. Such a starting date also coincides with James Watt's invention of the steam engine in 1784.[31]

Geoengineering (Climate intervention)

editSteve Connor, Science Editor of The Independent, wrote that Crutzen believes that political attempts to limit man-made greenhouse gases are so pitiful that a radical contingency plan is needed. In a polemical scientific essay that was published in the August 2006 issue of the journal Climatic Change, he says that an "escape route" is needed if global warming begins to run out of control.[32]

Crutzen advocated for climate engineering solutions, including artificially cooling the global climate by releasing particles of sulphur in the upper atmosphere, along with other particles at lower atmospheric levels, which would reflect sunlight and heat back into space. If this artificial cooling method actually were to work, it would reduce some of the effects of the accumulation of green house gas emissions caused by human activity, potentially extending the planet's integrity and livability.[33]

In January 2008, Crutzen published findings that the release of nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions in the production of biofuels means that they contribute more to global warming than the fossil fuels they replace.[34]

Nuclear winter

editCrutzen was also a leader in promoting the theory of nuclear winter. Together with John W. Birks he wrote the first publication introducing the subject: The atmosphere after a nuclear war: Twilight at noon (1982).[35] They theorized the potential climatic effects of the large amounts of sooty smoke from fires in the forests and in urban and industrial centers and oil storage facilities, which would reach the middle and higher troposphere. They concluded that absorption of sunlight by the black smoke could lead to darkness and strong cooling at the earth's surface, and a heating of the atmosphere at higher elevations, thus creating atypical meteorological and climatic conditions which would jeopardize agricultural production for a large part of the human population.[36]

In a Baltimore Sun newspaper article printed in January 1991, along with his nuclear winter colleagues, Crutzen hypothesized that the climatic effects of the Kuwait oil fires would result in "significant" nuclear winter-like effects; continental-sized effects of sub-freezing temperatures.[37]

Awards and honours

editCrutzen, Mario J. Molina, and F. Sherwood Rowland were awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1995 "for their work in atmospheric chemistry, particularly concerning the formation and decomposition of ozone".[4] Some of Crutzen's others honours include the below:

- 1976: Outstanding Publication Award, Environmental Research Laboratories, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration[38]

- 1984: Rolex-Discover Scientist of the Year.[38]

- 1985: Recipient of the Leó Szilárd Award for "Physics in the Publics Interest" of the American Physical Society.[38]

- 1986: Elected as a Fellow of the American Geophysical Union.[38]

- 1989: Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement.[39]

- 1990: Corresponding Member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences[40]

- 1995: Recipient of the Global Ozone Award for "Outstanding Contribution for the Protection of the Ozone Layer" by United Nations Environment Programme.[38]

- 1999: Foreign Member of the Russian Academy of Sciences.[41]

- 2006: Elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society (ForMemRS)[1]

- 2007: International Member of the American Philosophical Society[42]

- 2017: Honorary Member of the Royal Netherlands Chemical Society[43]

- 2019: Lomonosov Gold Medal[44]

Personal life

editIn 1956 Crutzen met Terttu Soininen, whom he married a few years later in February 1958. In December of the same year, the couple had a daughter. In March 1964, the couple had another daughter.[4]

Crutzen died aged 87 on 28 January 2021.[45]

References

edit- ^ a b "Professor Paul Crutzen ForMemRS: Foreign Member". London: Royal Society. Archived from the original on 5 October 2015.

- ^ "Paul Crutzen, who shared Nobel for ozone work, has died". AP NEWS. 28 January 2021.

- ^ Benner, Susanne, Ph.D. (29 January 2021). "Max Planck Institute for Chemistry mourns the loss of Nobel Laureate Paul Crutzen". idw-online.de.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "Paul J. Crutzen – Facts". NobelPrize.org. Archived from the original on 5 December 2018.

- ^ "Paul J. Crutzen – Curriculum Vitae". NobelPrize.org. Archived from the original on 18 October 2020.

- ^ An Interview – Paul Crutzen talks to Harry Kroto Freeview video by the Vega Science Trust.

- ^ Müller, Rolf (2022). "Paul Jozef Crutzen. 3 December 1933 – 28 January 2021". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 72: 127–156. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2022.0011. S2CID 251743974.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1995".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Paul J. Crutzen: The engineer and the ozone hole". ESA.int. 29 May 2007. Archived from the original on 30 December 2020.

- ^ Ramanathan, V.; Crutzen, P.J.; Kiehl, J.T.; Rosenfeld, D. (2001). "Aerosols, Climate, and the Hydrological Cycle". Science. 294 (5549): 2119–2124. Bibcode:2001Sci...294.2119R. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.521.1770. doi:10.1126/science.1064034. PMID 11739947. S2CID 18328444.

- ^ Ramanathan, V.; Crutzen, P.J.; Lelieveld, J.; Mitra, A.P.; Althausen, D.; et al. (2001). "Indian Ocean Experiment: An integrated analysis of the climate forcing and effects of the great Indo-Asian haze" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research. 106 (D22): 28, 371–28, 398. Bibcode:2001JGR...10628371R. doi:10.1029/2001JD900133.

- ^ Andreae, M.O.; Crutzen, P.J. (1997). "Atmospheric Aerosols: Biogeochemical Sources and Role in Atmospheric Chemistry". Science. 276 (5315): 1052–1058. doi:10.1126/science.276.5315.1052.

- ^ Dentener, F.J.; Carmichael, G.R.; Zhang, Y.; Lelieveld, J.; Crutzen, P.J. (1996). "Role of mineral aerosol as a reactive surface in the global troposphere". Journal of Geophysical Research. 101 (D17): 22, 869–22, 889. Bibcode:1996JGR...10122869D. doi:10.1029/96jd01818.

- ^ Crutzen, P.J.; Andreae, M.O. (1990). "Biomass Burning in the Tropics: Impact on Atmospheric Chemistry and Biogeochemical Cycles". Science. 250 (4988): 1669–1678. Bibcode:1990Sci...250.1669C. doi:10.1126/science.250.4988.1669. PMID 17734705. S2CID 22162901.

- ^ Crutzen, P.J.; Birks, J.W. (1982). "The atmosphere after a nuclear war: Twilight at noon". Ambio. 11 (2/3): 114–125. JSTOR 4312777.

- ^ Crutzen, P.J. (1970). "The influence of nitrogen oxides on the atmospheric content" (PDF). Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 96 (408): 320–325. doi:10.1002/qj.49709640815. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ^ Bekman, Stas. "24 Will commercial supersonic aircraft damage the ozone layer?". stason.org.

- ^ "Scientific Interest of Prof. Dr. Paul J. Crutzen". Mpch-mainz.mpg.de. Archived from the original on 14 October 2008. Retrieved 27 October 2008.

- ^ "Atmospheric Chemistry: Start Page". Atmosphere.mpg.de. Archived from the original on 8 November 2008. Retrieved 27 October 2008.

- ^ "Obituary Notice, Paul Crutzen, 1933–2021". Scripps Institution of Oceanography. 29 January 2021. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ Choi, Naeun (10 November 2008). "Nobel Prize Winner Paul Crutzen Appointed as SNU Professor". Useoul.edu. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- ^ Keisel, Greg (17 November 1995). "Nobel Prize winner at Tech". The Technique. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 22 May 2007.

- ^ "Catalogus Professorum – Prof Detail". profs.library.uu.nl. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ^ "repealcreationism.com | 522: Connection timed out". www.repealcreationism.com.

- ^ "Notable Signers". Humanism and Its Aspirations. American Humanist Association. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- ^ Paul J. Crutzen publications indexed by Google Scholar

- ^ "Scopus preview – Crutzen, Paul J. – Author details – Scopus". www.scopus.com. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ Schwartz, John (4 February 2021). "Paul Crutzen, Nobel Laureate Who Fought Climate Change, Dies at 87". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- ^ Zalasiewicz, Jan; Williams, Mark; Steffen, Will; Crutzen, Paul (2010). "The New World of the Anthropocene1". Environmental Science & Technology. 44 (7): 2228–2231. Bibcode:2010EnST...44.2228Z. doi:10.1021/es903118j. hdl:1885/36498. PMID 20184359.

- ^ Steffen, W.; Grinevald, J.; Crutzen, P.; McNeill, J. (2011). "The Anthropocene: conceptual and historical perspectives". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 369 (1938): 842–867. Bibcode:2011RSPTA.369..842S. doi:10.1098/rsta.2010.0327. ISSN 1364-503X. PMID 21282150.

- ^ "Opinion: Have we entered the "Anthropocene"?". IGBP.net. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- ^ Steve Connor (31 July 2006). "Scientist publishes 'escape route' from global warming". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 23 July 2008. Retrieved 27 October 2008.

- ^ Crutzen, Paul J. (August 2006). "Albedo enhancement by stratospheric sulfur injections: a contribution to resolve a policy dilemma?". Climatic Change. 77 (3–4): 211–219. Bibcode:2006ClCh...77..211C. doi:10.1007/s10584-006-9101-y.

- ^ Crutzen, P. J.; Mosier, A. R.; Smith, K. A.; Winiwarter, W (2008). "N2O release from agro-biofuel production negates global warming reduction by replacing fossil fuels" (PDF). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 8 (2): 389–395. Bibcode:2008ACP.....8..389C. doi:10.5194/acp-8-389-2008.

- ^ Paul J. Crutzen and John W. Birks: The atmosphere after a nuclear war: Twilight at noon Ambio, 1982 (abstract)

- ^ Gribbin, John; Butler, Paul (3 March 1990). "Science: A nuclear winter would 'devastate' Australia". NewScientist.com. Archived from the original on 13 April 2016. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ^ Roylance, Frank D. (23 January 1991). "Burning oil wells could be disaster, Sagan says". baltimoresun.com.

- ^ a b c d e "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1995". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ "Past Laureates". Tyler Prize.

- ^ "P.J. Crutzen". Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on 21 July 2015.

- ^ "Krutzen P .. – General information" (in Russian). Russian Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ "APS Member History".

- ^ Honorary members – website of the Royal Netherlands Chemical Society

- ^ "Paul J. Crutzen (1933–2021) :: ChemViews Magazine :: ChemistryViews". www.chemistryviews.org. 29 January 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ "The Max Planck Institute for Chemistry mourns the loss of its former director and Nobel Laureate Paul J. Crutzen". Max Planck Institute for Chemistry. 28 January 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

External links

edit- Paul J. Crutzen on Nobelprize.org including the Nobel Lecture, 8 December 1995 My Life with O3, NOx and Other YZOxs

- Memoirs Paul Jozef Crutzen. 3 December 1933—28 January 2021 auf The Royal Society Publishing (englisch)