Pair skating is a figure skating discipline defined by the International Skating Union (ISU) as "the skating of two persons in unison who perform their movements in such harmony with each other as to give the impression of genuine Pair Skating as compared with independent Single Skating".[1] The ISU also states that a pairs team consists of "one Woman and one Man".[2] Pair skating, along with men's and women's single skating, has been an Olympic discipline since figure skating, the oldest Winter Olympic sport, was introduced at the 1908 Summer Olympics in London. The ISU World Figure Skating Championships introduced pair skating in 1908.

| |

| Highest governing body | International Skating Union |

|---|---|

| Characteristics | |

| Team members | Pairs |

| Mixed-sex | Yes |

| Equipment | Figure skates |

| Presence | |

| Olympic | Part of the Summer Olympics in 1908 and 1920; Part of the first Winter Olympics in 1924 to today |

Like the other disciplines, pair skating competitions consist of two segments, the short program and the free skating program. There are seven required elements in the short program, which lasts two minutes and 40 seconds for both junior and senior pair teams. Free skating for pairs "consists of a well balanced program composed and skated to music of the pair's own choice for a specified period of time".[3] It also should contain "especially typical Pair Skating moves" such as pair spins, lifts, partner assisted jumps, spirals and other linking movements. Its duration, like the other disciplines, is four minutes for senior teams, and three and one-half minutes for junior teams. Pair skating required elements include lifts, twist lifts, throw jumps, jumps, spin combinations, death spirals, step sequences, and choreographic sequences. The elements performed by pairs teams must be "linked together by connecting steps of a different nature"[1] and by other comparable movements and with a variety of holds and positions. Pair skaters must only execute the prescribed elements; if they do not, the extra or unprescribed elements will not be counted in their score. Violations in pair skating include falls, time, music, and clothing.

Pair skating is the most dangerous discipline in figure skating; it has been compared to playing in the National Football League. Pair skaters have more injuries than skaters in other disciplines, and women pair skaters have more injuries than male pair skaters.

History

editBeginnings

editThe International Skating Union (ISU) defines pair skating as "the skating of two persons in unison who perform their movements in such harmony with each other as to give the impression of genuine Pair Skating as compared with independent Single Skating".[1] The ISU also states that a pair team consists of "one Woman and one Man"[2] and that "attention should be paid to the selection of an appropriate partner".[1][a]

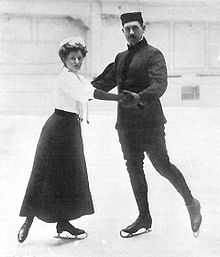

The roots of pairs skating, like ice dance, is in the "combined skating" developed in the 19th century by skating clubs and organizations and by recreational social skating between couples and friends, who would skate waltzes, marches, and other social dances together.[5] According to writer Ellyn Kestnbaum, the rising popularity of skating during the 19th century led to the development of figure skating techniques, especially the "various forms of hand-in-hand skating that would become the basis of pair skating".[6] Kestnbaum believes that there is no technical reason why pair skating moves could not be performed by opposite sexes because the moves emphasize the symmetry and similarity of the two bodies making them. Kestnbaum also states that men developed the original concepts of combined skating because most advanced skating was done by adult males. When women became more involved in the sport, they were allowed to compete in "similar pairs" competitions in the U.S.[7]

Figure skating historian James R. Hines reports that factors, such as hand-in-hand skating and "the crazelike fascination with ice dancing" in the mid-1890s, contributed to the development of pair skating.[8] Madge Syers, the first female figure skater to compete and win internationally, states that from the beginning of the introduction of pair skating in international competitions, it was a popular sport for audiences to watch, and that "if the pair are well matched and clever performers, it is undoubtedly the most attractive to watch".[9] When women began to compete in figure skating in the early 1900s, married couples developed routines together and provided female partners with the opportunities to demonstrate parity with their male partners by executing the same moves.[10] Syers states that Viennese skaters were responsible for pair skating's popularity at the beginning of the 20th century and credited the Austrians for adding dance moves to pair skating.[9]

At first, pair skating consisted of executing basic figures and side-by-side free-skating moves, such as long, flowing spirals done backwards or forwards, and connected with dance steps while couples held one or two hands.[8] Jumps and pirouettes were not required, and were done by only experienced pair skaters.[11] German pair skater Heinrich Burger, in his article in Irving Brokaw's The Art of Skating (1915), states that he and his partner, Anna Hübler, inserted figures skated by single skaters into "our several dances according to the music"[b] until the figures became more complicated and developed into a different appearance; as Burger puts it, "the fundamental character of the figure, however, has remained the same".[13] Also in the 1890s, combined and hand-in-hand skating moved skating away from "the static confines of basic figures to continuous movement around a rink".[14] Hines insists that the popularity of skating waltzes, which depended upon the speed and flow across the ice of couples in dance positions and not just on holding hands with a partner, "dealt a death knell to hand-in-hand skating".[14]

Early years

editPair skating, along with men's and women's single skating, has been an Olympic discipline since figure skating, the oldest Winter Olympic sport, was introduced at the 1908 Summer Olympics in London.[15] The ISU World Figure Skating Championships introduced pair skating, along with women's singles, also in 1908.[16] Hübler and Burger were the first Olympic gold medalists in pair skating in 1908; they also won the 1908 and 1910 World Championships. In 1936, Maxi Herber and Ernst Baier won the gold medal at the Olympics and went on to win the World Championships from 1936 to 1939.[17] The first pair skating national competitions in Canada occurred in 1905 and the first time pair skating was included during a U.S. Championships was in 1914, but there are only a few descriptions of pair skating in North America before World War I.[11] Side-by-side skating, also called shadow skating, in which partners executed the same movements and steps in unison, were emphasized in the early 1920s. Pair skating became more athletic in the 1930s; partners executed "a balanced blend of shadow skating coupled with increasingly spectacular pair moves, including spins, death-spirals, and lifts".[18] Hines credits German pair skaters Maxi Herber and Ernst Baier and French team Andrée Brunet and Pierre Brunet with developing athletic elements and programs that included pair spins, side-by-side spins, lifts, throw jumps, side-by-side jumps, and side-by-side footwork sequences.[18] By the 1930s, pair skating had advanced; Hines states, "It was not yet viewed equally with singles skating, at least from a technically standpoint, but it had grown to be a much-appreciated discipline".[19] Hines also reports that many single skaters during the era also competed in pair skating.[19]

Soviet and Russian domination in pair skating began in the 1950s and continued throughout the rest of the 1900s. Only five non-Soviet or Russian teams won the World Championships after 1965, until 2010.[20] Soviet pair teams won gold medals in seven consecutive Olympics, from 1964 in Innsbruck to 1988 in Calgary.[21] Kestnbaum credits the Soviets for emphasizing ballet, theater, and folk dance in all disciplines of figure skating, noting the influence of Soviet pair team and married couple Liudmila Belousova and Oleg Protopopov. The Protopopovs, as they were called, won gold medals at the 1964 and 1968 Olympics, as well as the 1968 World Championships, "raised by several degrees the level of translating classical dance to the ice".[22] Hines reports that the Protopopovs represented a new style of pair skating developed during the 1960s. He states, "A more flowing style presented by the Russians was replacing an older, more disconnected style".[23] The Protopopovs, like single skaters Sonja Henie in the 1930s and Dick Button in the 1940s, while winning multiple Olympic medals, "altered dramatically the direction of figure skating",[23] and marked the beginning of the Soviet domination of pair skating for the rest of the 20th century.[23] Irina Rodnina, with her partner Alexei Ulanov and later Alexander Zaitsev, also from the Soviet Union, dominated pair skating throughout the 1970s and "led the trend of female pair skaters as risk-taking athletes".[22] With Ulanov, Rodnina won World and European titles for four years in a row and an Olympic gold medal in 1972.[24][25] Hines reports that Rodnina and her second partner, Zaitsev, won the 1973 European Championships and were "never seriously challenged"[24] between 1974 and 1978, winning gold medals at the 1976 Olympics and at every World and European Championships during that period. They also won gold medals at the 1980 European Championships and at the Olympics that same year.[24] Hines states, about Rodnina and her partners, that they "transformed pair skating through expanded and inspired athleticism".[24]

Later years

editPair skating, which has never included a compulsory phase like the other figure skating disciplines, did not require a short program until the early 1960s, when the ISU "instituted a short program of required moves"[26] as the first part of pair competitions. Hines reports that the change was due "to a few controversial decisions in the 1950s and the discipline's increasing technical complexities".[27] In 1964, at the European Championships in Grenoble, France and the 1964 World Championships in Dortmund, West Germany, and during the Olympics in 1968, a two-and-a-half minute long technical program was added, later called the short program, which constituted one-third of a team's scores.[27] The arrangement of the specific moves, also unlike compulsory figures for single skaters and the compulsory dance for ice dancers, were up to each pair team. The short programs introduced in single men and women competitions in 1973 were modeled after the pair skating short program, and the structure of competitions in both single and pair competitions have been identical since the elimination of compulsory figures in 1990.[26]

A judging scandal at the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City, Utah "ushered in sweeping reforms in the scoring system"[28] of figure skating competitions. The scandal, which centered around Canadian pair team Jamie Sale and David Pelletier and Russian pair team Elena Berezhnaya and Anton Sikharulidze, brought about the end of the 6.0 scoring system and the implementation of the ISU Judging System, starting in 2004.[28][29]

According to Caroline Silby, a consultant with U.S. Figure Skating, pair teams, as well as ice dance teams, have the added challenge of strengthening partnerships and ensuring that teams stay together for several years. Silby states, "Conflict between partners that is consistent and unresolved can often lead to the early demise or break-up of a team".[30] Challenges for both pairs and dancers, which can make conflict resolution and communication difficult, include: the fewer number of available boys for girls to find partnerships; different priorities regarding commitment and scheduling; differences in partners' ages and developmental stages; differences in family situations; the common necessity of one or both partners moving to train at a new facility; and different skill levels when the partnership is formed.[31] Silby estimates that due to the lack of effective communication among pair teams, there is a "six-fold increase in the risk of national-level figure skating teams splitting".[32] Teams with strong skills in communication and conflict resolution, however, tend to produce "highest-placing finishers at national championship events".[32]

Competition segments

editShort program

editThe short program is the first segment of single skating, pair skating, and synchronized skating in international competitions, including all ISU championships, the Olympic Winter Games, the Winter Youth Games, qualifying competitions for the Olympic Winter Games, and ISU Grand Prix events for both junior and senior-level skaters (including the finals).[2] The short program must be skated before the free skate, the second component in competitions.[33] The short program lasts, for both senior and junior pair skaters, two minutes and 40 seconds.[34] Vocal music with lyrics has been allowed in pair skating and in all disciplines since the 2014–2015 season.[35]

Both junior and senior pair skaters have seven required elements: a lift, a twist lift, a throw jump, a jump; a solo spin combination, a death spiral, and a step sequence.[36] The sequence of the elements is optional. Like single skaters, the short programs of pair teams must be skated in harmony with the music, which they choose.[37] The short program for pair skating was introduced at the 1963 European Championships, the 1964 World Championships, and the Olympics in 1968; previously, pair skaters only had to perform the free skating program in competitions.[38]

Wenjing Sui and Cong Han from China hold the highest pair skating short program score of 84.41 points, which they earned at the 2022 Olympic Winter Games.[39][c]

Free skating

editAccording to the ISU, free skating for pairs "consists of a well balanced program composed and skated to music of the pair's own choice for a specified period of time".[41] The ISU also considers a well-done free skate one that contains both single skating moves performed either in parallel (called "shadow skating") or symmetrically (called "mirror skating"). It also should contain "especially typical Pair Skating moves" such as pair spins, lifts, partner assisted jumps, spirals linked harmoniously by steps and other movements.[41][d]

A well-balanced free skate for senior pairs must consist of the following: up to three pair lifts, not all from the same group, with the lifting arm or arms fully extended;[e] exactly one twist lift, exactly one solo jump; exactly one jump sequence or combination; exactly one pair spin combination; exactly one death spiral of a different type than what the skaters performed during their short program; and exactly one choreographic sequence. A well-balanced free skate for junior pairs must consist of the same elements required for senior teams, but with a maximum of two jumps and their death spiral does not have to be different to what they performed in their short program.[41] Its duration, like the other disciplines, is four minutes for senior teams, and three-and-one-half minutes for junior teams.[34]

Anastasia Mishina and Aleksandr Galliamov hold the highest pair free skating program score of 157.46 points, which they earned at the 2022 European Championships.[44]

Competition requirements

editPair skating today is arguably the most difficult discipline technically. Pair skaters do the same jumps and spins as single skaters, sometimes with fewer revolutions, but timing is far more critical because they must execute moves in perfect unison. In addition to jumps and spins, pair skaters perform lifts unique to their discipline. More intangible but no less important is the necessity for expressive and convincing interaction between partners as they interpret the music.

–Figure skating historian James Hines[45]

Pair skating required elements include pair lifts, twist lifts, throw jumps, jumps, spin combinations, death spirals, step sequences, and choreographic sequences.[46] The elements performed by pair teams must be "linked together by connecting steps of a different nature"[1] and by other comparable movements and with a variety of holds and positions. The team does not have to always execute the same movements and can separate from time to time, but they have to "give an impression of unison and harmony of composition of program and of execution of the skating".[1] They must limit movements executed on two feet, and must fully use the entire ice surface.[1] The ISU also states, about how programs are performed by pair skating teams, "Harmonious steps and connecting movements, in time to the music, should be maintained throughout the program".[43] The ISU published the first judges' handbook for pair skating in 1966.[47]

Pair lifts

editThere are five groups of pair skating lifts, categorized in order of increasing level of difficulty, and determined by the hold at the moment the woman passes the man's shoulder.[43]

- Group One: Armpit hold position

- Group Two: Waist hold position

- Group Three: Hand to hip or upper part of the leg (above the knee) position

- Group Four: Hand to hand position (Press Lift type)

- Group Five: Hand to hand position (Lasso Lift type)[48]

Judges look for the following when evaluating pair lifts: speed of entry and exit; control of the woman's free leg when she is exiting out of the lift, with the goal of keeping the leg high and sweeping; the position of the woman in the air; the man's footwork; quick and easy changes of position; and the maintenance of flow throughout the lift.[49] Judges begin counting how many revolutions pair teams execute from the moment when the woman leaves the ice until when the man's arm (or arms) begin to bend after he has made a full extension and the woman begins to descend.[50]

A complete pair skating lift must include full extension of the lifting arm or arms, if required for the type of lift being performed. Small lifts, or ones in which the man does not raise his hands higher than his shoulders, or lifts that include movements in which the man holds the woman by the legs, are also allowed. The man must complete at least one revolution.[51] The woman can perform both a simple take-off and a difficult take-off. A difficult take-off can include, but is not limited to, the following: a somersault take-off; a one-hand take-off; an Ina Bauer; a spread-eagle; spirals as the entry curve executed by one or both partners; or a dance lift followed immediately by a pair lift take-off. Difficult landings include, but are not limited to, the following: somersaults; one-hand landings; variations in holds; and spread-eagle positions of the man during dismounting.[52] Carry lifts are defined as "the simple carrying of a partner without rotation"[53] are allowed; they do not count as overhead lifts, but are considered as transition elements.[54] A lift is judged illegal if it is accomplished with a wrong hold.[55]

The only times pair skating partners can give each other assistance in executing lifts are "through hand-to-hand, hand-to-arm, hand-to-body and hand to upper part of the leg (above the knee) grips".[43] They are allowed changes of hold, or going from one of the grips to another or from one hand to another in a one-hand hold, during lifts.[43] Teams earn fewer points if the woman's position and a change of hold is executed at the same time.[50] They earn more points if the execution of the woman's position and the change in hold are "significantly different from lift to lift".[50] Teams can increase the difficulty of lifts in any group by using a one-hand hold.[56]

There are three types of positions performed by the woman: upright, or when her upper body is vertical; the star, or when she faces sideways with her upper body parallel to the ice; and the platter, or when her position is flat and facing up or down with her upper body parallel to the ice. The lifts ends when the man's arm or arms begins to bend after he completes a full extension and when the woman begins to descend.[43]

Twist lifts

editSkate Canada calls twist lifts "sometimes the most thrilling and exciting component in pair skating".[49] They can also be most difficult movement to perform correctly.[49] Judges look for the following when evaluating twist lifts: speed at entry and exit; whether or not the woman performs a split position while on her way to the top of the twist lift; her height once she gets there; clean rotations; a clean catch by the male (accomplished by placing both hands at the woman's waist and without any part of her upper body touching him); and a one-foot exit executed by both partners. A pair team can make twist lifts more complicated when the woman executes a split position (each leg is at least 45° from her body axis and her legs are straight or almost straight) before rotating. They also can earn more points when the man's arms are sideways and straight or almost straight after he releases the woman. Difficult take-offs include turns, steps, movements, and small lifts executed preceding the take-off and with continuous flow. Pair teams lose points for not having enough rotations, one-half a rotation or more.[49][57]

The first quadruple twist lift performed in international competition was by Russian pair team Marina Cherkasova and Sergei Shakhrai at the European Championship in 1977.[58]

Solo jumps and throw jumps

editSolo jumps

editPair teams, both juniors and seniors, must perform one solo jump during their short programs; it can include a double flip or double Axel for juniors, or any kind of double or triple jump for seniors. In the free skate, both juniors and seniors must perform only one solo jump and only one jump combination or sequence. A jump sequence consists of two jumps, with no limitations on the number of revolutions per jump. It starts with any type of jump, immediately followed by an Axel-type jump. Skaters must, during a jump combination, make sure that they land on the same foot they took off on, and that they execute a full rotation on the ice between the jumps. They can, however, execute an Euler between the two jumps. When the Euler is performed separately, it is considered a non-listed jump.[59] Junior pairs, during their short programs, earn no points for the solo jump if they perform a different jump than what is required. Both junior and senior pairs earn no points if, during their free skating programs, they repeat a jump with over two revolutions.[60]

All jumps are considered in the order in which they were performed. If the partners do not execute the same number of revolutions during a solo jump or part of a jump sequence or combination (which can consist of two or three jumps), only the jump with the fewer revolutions will be counted in their score. The double Axel and all triple and quadruple jumps, which have more than two revolutions, must be different from one another, although jump sequences and combinations can include the same two jumps. Extra jumps that do not fulfill the requirements are not counted in the team's score.[61] Teams are allowed, however, to execute the same two jumps during a jump combination or sequence. If they perform any or both jump or jumps incorrectly, only the incorrectly done jump is not counted and it is not considered a jump sequence or combination. Both partners can execute two solo jumps during their short programs, but the second jump is worth less points than the first.[60]

A jump attempt, in which one or both partners execute a clear preparation for a take-off but step to the entry edge or place their skate's toe pick into the ice and leave the ice with or without a turn, counts as one jump element. If the partners execute an unequal number of rotations during a solo jump or as part of a jump combination or sequence, the jump with the lesser number of revolutions will be counted. They receive no points if they perform different types of jumps. A small hop or a jump with up to one-half revolution (considered "decoration") is not marked as a jump and called a "transition" instead. Non-listed jumps do not count as jumps, either, but can also be called a transition and can be used as "a special entrance to the jump".[62] If the partners execute a spin and a jump back to back, or vice versa, they are considered separate elements and the team is awarded more points for executing a difficult take-off or entry. They lose points if the partners fall or step out of a jump during a jump sequence or combination.[60]

Throw jumps

editThrow jumps are "partner assisted jumps in which the Lady is thrown into the air by the Man on the take-off and lands without assistance from her partner on a backward outside edge".[63] Skate Canada says, "the male partner assists the female into flight".[49] Many pair skaters consider the throw jump "a jump rather than a throw".[64] The throw jump is also considered an assisted jump, performed by the woman. The man supports the woman, initiates her rotations, and assists her with her height, timing, and direction.[64]

The types of throw jumps include: the throw Axel, the throw salchow, the throw toe loop, the throw loop, the throw flip, and the throw Lutz. The speed of the team's entry into the throw jump and the number of rotations performed increases its difficulty, as well as the height and/or distance they create.[49] Pair teams must perform one throw jump during their short programs; senior teams can perform any double or triple throw jump, and junior teams must perform a double or triple Salchow. If the throw jump does not satisfy the requirements as described by the ISU, including if it has the wrong number of revolutions, it receives no value.[65]

The first throw triple Axel jump performed in competition was by American pair team Rena Inoue and John Baldwin Jr. at the 2006 U.S. Championships. They also performed it at the Four Continents Championships in 2006 and the 2006 Winter Olympics.[66] The throw triple Axel is a difficult throw to accomplish because the woman must perform three-and-one-half revolutions after being thrown by the man, a half-revolution more than other triple jumps, and because it requires a forward take-off.[67]

-

Deanna Stellato-Dudek & Maxime Deschamps set up for a throw jump.

-

Evelyn Walsh & Trennt Michaud set up for a throw jump.

-

Ashley Cain rotates after being thrown by Timothy LeDuc.

-

Aleksandra Boikova rotates after being thrown by Dmitrii Kozlovskii.

-

Anabelle Langlois lands after performing a throw jump with Cody Hay.

Spins

editSolo spin combinations

editThe solo spin combination must be performed once during the short program of pair skating competitions, with at least two revolutions in two basic positions. Both partners must include all three basic positions in order to earn the full points possible. There must be a minimum of five revolutions made on each foot.[68] Spins can be commenced with jumps and must have at least two different basic positions, and both partners must include two revolutions in each position. A solo spin combination must have all three basic positions (the camel spin, the sit spin, and upright positions) performed by both partners, at any time during the spin to receive the full value of points, and must have all three basic positions performed by both partners to receive full value for the element. A spin with less than three revolutions is not counted as a spin; rather, it is considered a skating movement. If a skater changes to a non-basic position,[f] it is not considered a change of position. The number of revolutions in non-basic positions, which may be considered difficult variations, are counted towards the team's total number of revolutions. Only positions, whether basic or non-basic, must be performed by the partners at the same time.[70][69]

If a skater falls while entering into the spin, he or she can perform another spin or spinning movement immediately after the fall, to fill the time lost from the fall, but it is not counted as a solo spin combination. A change of foot, in the form of a jump or step over, is allowed, and the change of position and change of foot can be performed separately or at the same time.[68] Pair teams require "significant strength, skill and control"[69] to perform a change from a basic position to a different basic position without performing a nonbasic position first. They also have to execute a continuous movement throughout the change, without jumps to execute it, and they must hold the basic position for two revolutions both before and after the change.[69] They lose points if they take a long time to reach the necessary basic position.[71]

Pair teams earn more points for performing difficult entrances and exits.[68] An entrance is defined as "the preparation immediately preceding a spin",[72] including a flying entrance by one or both partners; it can include the spin's beginning phase.[72][73] All entrances must have a "significant impact"[72] on the spin's execution, balance, and control, and must be completed on the first spinning foot. The intended spin position must be achieved within the team's first two revolutions, and can be non-basic in spin combinations only.[72] An exit is defined as "the last phase of the spin";[72] it can include the phase immediately following the spin. Like the entrance, an exit must have a "significant impact"[72] on the spin's execution, balance, and control.[72] There are 11 categories of difficult solo spin variations.[g]

Spin combinations

editBoth junior and senior pair teams must perform one pair spin combination, which may begin with a fly spin, during their free skating programs.[73] Pair spin combinations must have at least eight revolutions, which must be counted from "the entry of the spin until its exit".[75] If spins are done with less than two revolutions, pairs receive zero points; if they have less than three revolutions, they are considered a skating movement, not a spin. Pair teams cannot, except for a short step when changing directions, stop while performing a rotation.[75][73] Spins must have at least two different basic positions, with two revolutions in each position performed by both partners anywhere within the spin; full value for pair spin combinations are awarded only when both partners perform all three basic positions.[70] A spin executed in both clockwise and counter-clockwise directions is considered one spin. When a team simultaneously performs spins in both directions that immediately follow each other, they earn more points, but they must execute a minimum of three revolutions in each direction without any changes in position.[76]

Both partners must execute at least one change of position and one change of foot (although not necessarily done simultaneously); if not, the element will have no value.[77] Like the solo spin combination, the spin combination has three basic positions: the camel spin, the sit spin, and the upright spin. Also like the solo spin combination, changes to a non-basic position is counted towards the team's total number of revolutions and are not considered a change of position. A change of foot must have at least three revolutions, before and after the change, and can be any basic or non-basic position, in order for the element to be counted.[78] The woman is allowed to be lifted from the ice during the spin, but her partner must stay on one foot, and the revolutions they execute while in the air counts towards the total number of revolutions. The ISU states that this does not increase the difficulty of a combination spin, but it does allow for creativity.[76]

Fluctuations of speed and variations of positions of the head, arms, or free leg are allowed.[68] Difficult variations of a combined pair spin must have at least two revolutions. They receive more points if the spin contains three difficult variations, two of which can be non-basic positions, although each partner must have at least one difficult variation. The same rules apply for difficult entrances into pair spin combinations as they do for solo spin combinations, except that they must be executed by both partners for the element to count towards their final score.[76] A difficult exit, in which the skaters exit the spin in a lift or spinning movement, is defined as "an innovative move that makes the exit significantly more difficult";[76] Also like the solo spin combination, the exit must have "significant impact on the balance, control and execution of the spin".[76] If one or both partners fall while entering a spin, they can execute a spin or a spinning movement to fill up time lost during the fall.[73]

Death spirals

editThe death spiral is "a circular move in which the male lowers his partner to the ice while she is arched backwards gliding on one foot".[49] There are four types of death spirals: the forward inside death spiral, the backward inside death spiral, the backward outside death spiral, and the forward outside death spiral.[79] According to Skate Canada, the forward inside death spiral is the easiest one to execute, and the forward outside death spiral is the most difficult.[49][h]

The death spiral performed in the short program at the senior level must be different from the death spiral during the free skating program.[41] In the 2022–2023 season, both junior and senior pair teams must perform the backward inside death spiral. In 2023–2024, both juniors and seniors had to perform the forward inside death spiral.[80] If a different death spiral other than what has been prescribed is executed, it receives no points.[81] One death spiral is required for juniors and seniors during their free skate.[41][79]

Step sequences

editStep sequences in pair skating should be performed "together or close together".[41] Step sequences must be a part of the short program, but they are not required in the free skating program. There is no required pattern, but pair teams must fully use the ice surface.[81][82] The step sequence must be "visible and identifiable",[82] and teams must use the full ice surface (oval, circle, straight line, serpentine, or similar shape). The team must skate three meters or less near each other while executing the crossing feature of the sequence.[83] They must not separate, with no breaks, for at least half of the sequence. Changes of holds, which can include "a brief moment" when the partners do not touch, are permitted during the step sequence.[84]

The workload between the partners must be even to help them earn more points. More points are rewarded to teams when they change places or holds, or when they perform difficult skating moves together.[63] Both partners must execute the combinations of difficult turns at the same time and with a clear rhythm and continuous flow. Partners can perform rockers, counters, brackets, loops, and twizzles during combinations of difficult turns. Three turns, changes of edges, jumps and/or hops, and changes of feet are not allowed, and "at least one turn in the combination must be of a different type than the others".[85] Two combinations of difficult turns are the same if they consist of the same turns performed in the same order, on the same foot and on the same edges.[82]

Choreographic sequences

editPair teams must perform one choreographic sequence during their free skating programs.[86] According to the ISU, a choreographic sequence "consists of at least two different movements like steps, turns, spirals, arabesques, spread eagles, Ina Bauers, hydroblading, any jumps with maximum of 2 revolutions, spins, etc.".[87] Pair skating teams can use steps and turns to connect the two or more movements together.[87][i] It begins at the first skating movement and ends when the team begins to prepare to execute the next element, unless the sequence is the last element performed during the program. Judges do not evaluate individual elements in a choreographic segment; rather, they note that it was accomplished. There are no restrictions limiting the sequence of the movements, but the sequence must be "clearly visible".[88] Pair skaters, in order to earn the most points possible, must include the following in their choreographic sequences: they must have originality and creativity; the sequence must match the music and reflect the program's concept and character; and they must demonstrate effortlessness of the element as a sequence. They must also do the following: "have good ice coverage" or perform an interesting pattern; demonstrate good unison between the partners; and demonstrate "excellent commitment" and control of the whole body.[89]

Rules and regulations

editSkaters must only execute the prescribed elements; if they do not, the extra or unprescribed elements will not be counted in their score. Only the first attempt of an element will be included.[90] Violations in pair skating include falls, time, music, and clothing.

Falls

editAccording to the ISU, a fall is defined as the "loss of control by a Skater with the result that the majority of his/her own body weight is on the ice supported by any other part of the body other than the blades; e.g. hand(s), knee(s), back, buttock(s) or any part of the arm".[91] For pair skaters, one point is deducted for every fall by one partner, and two points are deducted for every fall by both partners.[92] According to former American figure skater Katrina Hacker, falls associated with jumps occur for the following reasons: the skater makes an error during their takeoff; their jump is under-rotated, or not fully rotated while they are in the air; they execute a tilted jump and is unable to land upright on their feet; and they make an error during the first jump of a combination jump, resulting in not having enough smoothness, speed, and flow to complete the second jump.[93]

Time

editAs for all skating disciplines, judges penalize pair skaters one point up to every five seconds for ending their programs too early or too late. If they start their programs between one and 30 seconds late, they can lose one point.[94] Restrictions for finishing the short program and the free skating program are similar to the requirements of the other disciplines in figure skating. Pair teams can complete these programs within plus or minus 10 seconds of the required times; if they cannot, judges can deduct points if they finish up to five seconds too early or too late. If they begin skating any element after their required time (plus the required 10 seconds they have to begin), they earn no points for those elements. The pair team receive no points if the duration of their program is completed less than 30 seconds or more seconds early.[34]

Music

editThe ISU defines the interpretation of the music in all figure skating disciplines as "the personal, creative, and genuine translation of the rhythm, character and content of music to movement on ice".[95] Judges take the following things into account when scoring the short program and the free skating program: the steps and movement in time to the music; the expression of the character of the music; and the use of finesse.[j]

The use of vocals was expanded to pair skating, as well as to single skating, starting in 2014; the first Olympics affected by this change was in 2018 in PyeongChang, South Korea.[96][k] The ISU's decision, done to increase the sport's audience, to encourage more participation, and to give skaters and choreographers more choice in constructing their programs, had divided support among skaters, coaches, and choreographers.[97][98]

If the quality or tempo of the music the team uses in their program is deficient, or if there is a stop or interruption in their music, no matter the reason, they must stop skating when they become aware of the problem or when signaled to stop by a skating official, whichever occurs first. If any problems with the music happens within 20 seconds after they have begun their program, the team can choose to either restart their program or to continue from the point where they have stopped performing. If they decide to continue from the point where they stopped, they are continued to be judged at that point onward, as well as their performance up to that point. If they decide to restart their program, they are judged from the beginning of their restart and what they had done previously must be disregarded. If the music interruption occurs more than 20 seconds after they have begun their program, or if it occurred during an element or at the entrance of an element, they must resume their program from the point of the interruption. If the element was identified before the interruption, the element must be deleted from the list of performed elements, and the team is allowed to repeat the element when they resume their program. No deductions are counted for interruptions due to music deficiencies.[99]

Clothing

editAs for the other disciplines of figure skating, the clothing worn by pair skaters at ISU Championships, the Olympics, and international competitions must be "modest, dignified and appropriate for athletic competition—not garish or theatrical in design".[100] Props and accessories are not allowed. Clothing can reflect the character of the skaters' chosen music and must not "give the effect of excessive nudity inappropriate for the discipline".[100] All men must wear full-length trousers, a rule that has been in effect since the 1994–1995 season.[100][101][102] Since 2003, women skaters have been able to wear skirts, trousers, tights, and unitards.[101][103] Decorations on costumes must be "non-detachable";[100] judges can deduct one point per program if part of the competitors' costumes or decorations fall on the ice.[94] If there is a costume or prop violation, the judges can deduct one point per program.

Clothing that does not adhere to these guidelines will be penalized by a deduction. If competitors do not adhere to these guidelines, the judges can deduct points from their total score.[100] However, costume deductions are rare. Juliet Newcomer from U.S. Figure Skating states that by the time skaters get to a national or world championship, they have received enough feedback about their costumes and are no longer willing to take any more risks of losing points.[101] As former competitive skater and designer Braden Overett told the New York Post, there is "an informal review process before major competitions such as the Olympics, during which judges communicate their preferences".[104]

Also according to the New York Post, one of the goals of skaters and designers is to ensure that a costume's design, which can "make or break a performance", does not affect the skaters' scores.[104] Former competitive skater and fashion writer Shalayne Pulia states that figure skating costume designers are part of a skater's "support team".[105] Designers collaborate with skaters and their coaches to help them design costumes that fit the themes and requirements of their programs for months before the start of each season.[103] There have been calls to require figure skaters to wear uniforms like other competitive sports, in order to make the sport less expensive and more inclusive, and to emphasize its athletic side.[106]

Injuries

editAustralian single skater and coach Belinda Noonan states that "Pairs skating is literally physically more dangerous than the other three disciplines".[107] American pair skater Nathan Bartholomay agrees, comparing the danger in pair skating to playing in the National Football League.[108] Sportswriter Sandra Loosemore, in her discussion of the accidents in all figure skating disciplines, states that the "very nature" of pair skating "adds an extra dimension of danger and risk of injury"[109] because of the high speed and close proximity pair teams skate to each other, and the lifts and other elements in pair skating. Both members of a pair skating team can receive broken noses and other injuries from performing twist lifts incorrectly, and although male partners are taught to protect their partners in case of a fall from an overhead lift, concussions and serious head injuries are common. The ISU has banned and restricted dangerous tricks and moves from pair skating, but both skating audiences and skaters have demanded them. Skaters have resisted using protective gear, even during practice, because it interferes with developing self-confidence and is seen as incompatible with "the aesthetic aspects of the sport".[109]

A study conducted during a U.S. national competition including 60 pair skaters recorded an average of 1.83 injuries per athlete,[110] the most of any figure skating discipline. Single skaters and ice dancers have more lower body injuries, but pair skaters suffer more upper body injuries, "with 50% occurring to the head (e.g., facial lacerations, concussions)".[111] According to figure skating researchers Jason Vescovi and Jaci VanHeest, these injuries are "an obvious consequence of the throws and side-by-side jumps performed in this discipline".[111] A study conducted in 1989 found that ice dancers and pair skaters, during a nine-month period of time, can experience serious injuries (defined as the athletes missing seven or more consecutive days of training after their injuries), and that women pair skaters have more injuries than men, which Vescovi and VanHeest attributed to the demands of pair skating.[111]

Doping

editIn a 1991 interview, Olympic champion Irina Rodnina admitted that Soviet male pair skaters used doping substances in preparation for the competitive season, stating: "Boys in pairs and singles used drugs, but this was only in August or September. This was done just in training, and everyone was tested (in the Soviet Union) before competitions."[112]

Footnotes

edit- ^ Women were referred to as ladies in ISU regulations and communications until the 2021–22 season.[4]

- ^ Hines says that Burger and Hübler were known for their strength and speed, and for skating "in time with the music".[12]

- ^ After the 2018–2019 season, due to the change in grade of execution scores from −3 to +3 to −5 to +5, all statistics started from zero and all previous scores were listed as "historical".[40]

- ^ Writer Ellyn Kestnbaum defines shadow skating as "the same moves performed side-by-side in close proximity and in the same direction" and mirror skating as "the same moves performed side-by-side in opposite directions".[42]

- ^ See the 2021 "Special Regulations and Technical Rules" for a list of pair skating lift groups.[43]

- ^ A non-basic position is defined as "all the other positions not fulfilling the requirements of any basic positions".[69]

- ^ See the 2020/2021 Technical Panel Handbook.[74]

- ^ See the 2021/2022 Technical Panel Handbook for descriptions of the types of death spirals.[79]

- ^ If a team performs a jump with more than two revolutions, the sequence is considered ended at the commencement of the jump.[86]

- ^ "Finesse" is defined as "the Skater's refined, artful manipulation of music details and nuances through movement".[95] Each skater has a unique finesse and demonstrates their inner feelings for the composition and the music.[95] "Nuances" are "the personal ways of bringing subtle variations to the intensity, tempo, and dynamics of the music made by the composer and/or musicians".[95]

- ^ The ISU has allowed vocals in the music used in ice dance since the 1997–1998 season.[96]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g S&P/ID 2021, p. 109

- ^ a b c S&P/ID 2021, p. 9

- ^ S&P/ID 2021, p. 106

- ^ "Results of Proposals in Replacement of the 58th Ordinary ISU Congress 2021" (Press release). Lausanne, Switzerland: International Skating Union. 30 June 2021. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ Kestnbaum (2003), pp. xiv, 102.

- ^ Kestnbaum (2003), pp. 61–62.

- ^ Kestnbaum, pp. 217—201

- ^ a b Hines (2006), p. 82.

- ^ a b Syers, Edgar; Syers, Madge (1908). The Book of Winter Sports. London: Edward Arnold. p. 121. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- ^ Kestnbaum, p. 218

- ^ a b Hines (2006), p. 125.

- ^ Hines (2011), p. 47.

- ^ Burger, Heinrich (1915). "Pair-Skating". In Brokaw, Irving (ed.). The Art of Skating. New York: American Sports Publishing Company. p. 132. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- ^ a b Hines (2006), p. 119.

- ^ "History of Figure Skating". Olympic.org. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- ^ "ISU Archives – History of Figure Skating". Lausanne, Switzerland: International Skating Union. 2 November 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- ^ Hines (2011), p. 6.

- ^ a b Hines (2006), p. 126.

- ^ a b Hines (2006), p. 127.

- ^ Hines (2011), p. 191.

- ^ Janofsky, Michael (17 February 1988). "Soviet Skaters Prevail in Pairs". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- ^ a b Kestnbaum (2003), p. 112.

- ^ a b c Hines (2006), p. 190.

- ^ a b c d Hines (2006), p. 213.

- ^ Hines (2006), p. 337.

- ^ a b Kestnbaum (2003), p. 325.

- ^ a b Hines (2006), p. 197.

- ^ a b "Figure Skating Scandal at 2002 Games Ushered in Scoring Reform". CBC.CA. Thomson Reuters. 12 January 2018. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- ^ Carroll, Charlotte (5 December 2017). "A Rookie's Guide to Figure Skating at the 2018 Winter Olympics". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- ^ Silby (2018), p. 92.

- ^ Silby (2018), pp. 92–93.

- ^ a b Silby (2018), p. 93.

- ^ S&P/ID 2021, p. 10

- ^ a b c S&P/ID 2021, p. 76

- ^ Root, Tik (8 February 2018). "How to Watch Figure Skating at the 2018 Winter Olympics in PyeongChang". The Washington Post. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ S&P/ID 2021, pp. 113–115

- ^ S&P/ID 2021, pp. 111–112

- ^ Hines (2011), p. 205.

- ^ "Personal Best: Pairs Short Program Score". International Skating Union. 15 April 2022. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ^ Walker, Elvin (27 October 2018). "New Season New Rules". International Figure Skating. Archived from the original on 24 October 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f S&P/ID 2021, p. 115

- ^ Kestnbaum (2003), p. 217.

- ^ a b c d e f S&P/ID 2021, p. 110

- ^ "Personal Best: Pairs Free Skating Score". International Skating Union. 15 April 2022. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ^ Hines (2006), p. 124.

- ^ S&P/ID 2022, pp. 110–111

- ^ Hines (2011), p. xxv.

- ^ Tech panel, p. 22

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Skating Glossary". Skate Canada. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ^ a b c Tech panel, p. 23

- ^ S&P/ID 2021, p. 112

- ^ Tech panel, p. 20

- ^ S&P/ID 2021, p. 116

- ^ S&P/ID 2021, p. 118

- ^ S&P/ID 2021, p. 102

- ^ Tech panel, p. 24

- ^ Tech Panel, p. 26

- ^ Hines (2011), p. 57.

- ^ Tech Panel, p. 15

- ^ a b c Tech Panel, p. 17

- ^ S&P/ID 2021, pp. 111, 116

- ^ Tech Panel, p. 16

- ^ a b S&P/ID 2021, pp. 111

- ^ a b Brannen, Sarah S. (16 May 2012). "Element of Drama: A Look at Pairs Throw Jumps". Icenetwork.com. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ^ Tech Panel, p. 18

- ^ "ISU Figure Skating Media Guide 2021/22". International Skating Union. 20 April 2022. p. 19. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ^ Henderson, John (26 January 2006). "Duo Throws Caution to Wind". The Denver Post. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d Tech Panel, p. 7

- ^ a b c d Tech Panel, p. 8

- ^ a b S&P/ID 2021, p. 113

- ^ Tech Panel, p. 10

- ^ a b c d e f g Tech panel, p. 9

- ^ a b c d Tech Panel, p. 12

- ^ Tech Panel, p. 9

- ^ a b S&P/ID 2021, p. 119

- ^ a b c d e Tech Panel, p. 14

- ^ S&P/ID 2021, pp. 113, 119

- ^ Tech Panel, p. 13

- ^ a b c Tech Panel, p. 28

- ^ S&P/ID 2021, pp. 112–113

- ^ a b S&P/ID 2021, p. 114

- ^ a b c Tech Panel, p. 3

- ^ Tech Panel, pp. 3, 4

- ^ Tech Panel, p. 5

- ^ Tech Panel, p. 4

- ^ a b Tech Panel, p. 6

- ^ a b "Communication No. 2494: Single & Pair Skating/Ice Dance". Lausanne, Switzerland: International Skating Union. 30 June 2022. p. 4. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- ^ S&P/ID 2021, p. 117

- ^ "Communication No. 2254: Single & Pair Skating". Lausanne, Switzerland: International Skating Union. 21 May 2019. p. 7. Archived from the original on 2 July 2020. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ S&P/ID2021, p. 16

- ^ S&P/ID2021, pp. 76–77

- ^ S&P/ID2021, p. 18

- ^ Abad-Santos, Alexander (11 February 2014). "Why Figure Skaters Fall: A GIF Analysis". The Atlantic Monthly. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ a b S&P/ID 2021, p. 18

- ^ a b c d S&P/ID 2021, p. 80

- ^ a b Hersh, Philip (23 October 2014). "Figure Skating Taking Cole Porter Approach: Anything Goes". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ Clarey, Christopher (18 February 2014). "'Rhapsody in Blue' or Rap? Skating Will Add Vocals". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ Clarke, Liz (8 February 2018). "Will the Addition of Lyrics Have Olympic Figure Skating Judges Singing Along?". The Washington Post. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ ISU No. 2403, p. 79

- ^ a b c d e S&P/ID 2021, p. 78

- ^ a b c Yang, Nancy (21 January 2016). "What Not to Wear: The Rules of Fashion on the Ice". MPR News. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ Kestnbaum (2003), p. 186.

- ^ a b Muther, Christopher (11 January 2014). "The Ice Rink Becomes the Runway for Female Figure Skaters". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ a b Santiago, Rebecca (16 February 2018). "The Surprising Engineering Behind Olympic Skaters' Costumes". New York Post. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ Pulia, Shalayne (8 December 2017). "Inside the Niche, Glittery World of Figure Skating Dressmaking". InStyle Magazine. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ Lukas, Paul (14 December 2017). "How Can an International Sport Need a Costume?". ESPN.com. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ Armstrong, Kerrie (15 May 2017). "Breaking the Ice". Special Broadcasting Service Corporation. Sydney, Australia. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ Anderson, Chris (10 February 2014). "Danger Lurks in Pairs Skating". Herald-Tribune. Sarasota, Florida. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ a b Loosemore, Sandra (17 October 1999). "Falls, Injuries Often Come in Pairs". CBS Sports. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ Fortin, Joseph D.; Roberts, Diana (2003). "Competitive Figure Skating Injuries". Pain Physician. 6 (3): 313, 314. doi:10.36076/ppj.2003/6/313. PMID 16880878. Cited in Vescovi & VanHeest (2018, p. 36).

- ^ a b c Vescovi, Jason D.; VanHeest, Jaci L. (2018). "Epidemiology of injury in figure skating". In Vescovi, Jason D.; VanHeest, Jaci L. (eds.). The Science of Figure Skating. New York: Routledge. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-138-22986-0.

- ^ Hersh, Phil (February 14, 1991). "Rodnina Confirms Soviet Steroid Use". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018.

Works cited

edit- "Communication No. 2403: Summary of Results of Mail Voting on Proposals in Replacement of the 58th Ordinary Congress 2021". Lausanne, Switzerland: International Skating Union. 30 June 2021. Retrieved 17 July 2021 (ISU No. 2403).

- Hines, James R. (2006). Figure Skating: A History. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-07286-4.

- Hines, James R. (2011). Historical Dictionary of Figure Skating. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6859-5.

- Kestnbaum, Ellyn (2003). Culture on Ice: Figure Skating and Cultural Meaning. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 0819566411.

- Silby, Caroline (2018). "Mental Skills Training". In Vescovi, Jason D.; VanHeest, Jaci L. (eds.). The Science of Figure Skating. New York: Routledge. pp. 85–97. ISBN 978-1-138-22986-0.

- "Special Regulations & Technical Rules Single & Pair Skating and Ice Dance 2021". International Skating Union. June 2021. Retrieved 15 July 2022 (S&P/ID 2021).

- "ISU Judging System: Technical Panel Handbook: Pair Skating 2021/2022" Archived 2023-08-03 at the Wayback Machine (PDF). International Skating Union. 8 July 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2022 (Tech Panel).