The ivory gull (Pagophila eburnea) is a small gull, the only species in the genus Pagophila. It breeds in the high Arctic and has a circumpolar distribution through Greenland, northernmost North America, and Eurasia.

| Ivory gull | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Laridae |

| Genus: | Pagophila Kaup, 1829 |

| Species: | P. eburnea

|

| Binomial name | |

| Pagophila eburnea (Phipps, 1774)

| |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Taxonomy

editThe ivory gull was initially described by Constantine Phipps, 2nd Baron Mulgrave in 1774 as Larus eburneus from a specimen collected on Spitsbergen during his 1773 expedition towards the North Pole.[2] Johann Jakob Kaup later recognized the unique traits of the ivory gull and gave it a monotypic genus, Pagophila, in 1829.[2] Johan Ernst Gunnerus later gave the species a new specific name, Pagophila alba.[2][dubious – discuss] The genus name Pagophila is from Ancient Greek pagos, "sea-ice", and philos, "-loving", and specific eburnea is Latin for "ivory-coloured", from ebur, "ivory".[3] Today some authors consider the ivory gull not deserving of its monotypic genus, instead choosing to merge it, along with the other monotypic gulls, back into Larus.[2] However, most authors have not chosen to do so. The ivory gull has no subspecies.[2] No fossil members of this genus are known.[4]

This gull has traditionally been believed to be most closely related to either the kittiwakes, Sabine's gull, or Ross's gull.[2] It differs anatomically from the other genera by having a relatively short tarsometatarsus, a narrower os pubis, and potentially more flexibility in skull kinetic structure.[2] Structurally, it is most similar to the kittiwakes; however, recent genetic analysis based on mtDNA sequences shows that Sabine's gull is the ivory gull's closest relative, followed by the kittiwakes, with Ross's gull and swallow-tailed gull sharing a clade with these species.[2][5] Pagophila is maintained as a unique genus because of the bird's morphological, behavioral and ecological differences from these species.[2]

Colloquial names from Newfoundland include slob gull (from "slob", a local name for drift ice) and ice partridge, from a vague resemblance to a ptarmigan.[6]

Description

editThis species is easy to identify. At approximately 43 centimetres (17 in), it has a different, more pigeon-like shape than the Larus gulls, but the adult has completely white plumage, lacking the grey back of other gulls. The thick bill is blue with a yellow tip, and the legs are black. The bill is tipped with red, and the eyes have a fleshy, bright red eye-ring in the breeding season. Its flight call cry is a harsh, tern-like keeeer. It has many other vocalizations, including a warbling "fox-call" that indicates potential predators such as an Arctic fox, polar bear, Glaucous Gull or human near a nest, a "long-call" given with wrists out, elongated neck and downward-pointed bill, given in elaborate display to other Ivories during breeding, and a plaintive begging call given in courtship by females to males, accompanied by head-tossing. Young birds have a dusky face and variable amounts of black flecking in the wings and tail. The juveniles take two years to attain full adult plumage. There are no differences in appearance across the species’ geographic range.[2]

Measurements:[7]

- Length: 15.8–16.9 in (40–43 cm)

- Weight: 15.8–24.2 oz (450–690 g)

- Wingspan: 42.5–47.2 in (108–120 cm)

Distribution and habitat

editIn North America, it only breeds in the Canadian Arctic.[4] Seymour Island, Nunavut is home to the largest known breeding colony, while Ellesmere, Devon, Cornwallis, and north Baffin islands are known locations of breeding colonies.[4] It is believed that there are other small breeding colonies of less than six birds that are still undiscovered.[4] There are no records of the ivory gull breeding in Alaska.[4]

During the winter, ivory gulls live near polynyas, or a large area of open water surrounded by sea ice.[4] North American birds, along with some from Greenland and Europe, winter along the 2000 km of ice edge stretching between 50° and 64° N from the Labrador Sea to Davis Strait that is bordered by Labrador and southwestern Greenland.[4] Wintering gulls are often seen on the eastern coasts of Newfoundland and Labrador and occasionally appear on the north shore of the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the interior of Labrador.[4] It also winters from October through June in the Bering Sea and Chukchi Seas.[4] It is most widespread throughout the polynyas and pack ice of the Bering Sea.[4] It is also vagrant throughout coastal Canada and the northeastern United States, though records of individuals as far south as California and Georgia have been reported, as well as The British Isles, with most records from late November through early March.[4] Juveniles tend to wander further from the Arctic than adults.[4]

Ecology and behavior

editIvory gulls migrate only short distances south in autumn, most of the population wintering in northern latitudes at the edge of the pack ice, although some birds reach more temperate areas.

Diet

editIt takes fish and crustaceans, rodents, eggs and small chicks but is also an opportunist scavenger, often found on seal or porpoise corpses. It has been known to follow polar bears and other predators to feed on the remains of their kills.

Reproduction

editThe ivory gull breeds on Arctic coasts and cliffs, laying one to three olive eggs in a ground nest lined with moss, lichens, or seaweed.

Status

editIn 2012 the total population of ivory gulls was estimated to be between 19,000 and 27,000 individuals.[1] The majority of these were in Russia with 2,500–10,000 along the Arctic coastline, 4,000 on the Severnaya Zemlya archipelago[8] and 8,000 on Franz Josef Land and Victoria Island. There were also estimated to be around 4,000 individuals in Greenland[9] and in the years 2002–03, 500–700 were recorded in Canada.[1] Examination of data collected on an icebreaker plying between Greenland and Svalbard between 1988 and 2014, by Claude Joiris of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, found a sevenfold fall in ivory gull numbers after 2007.[10] The species is rapidly declining in Canada, while in other parts of its range its population is poorly known. The Canadian population in the early 2000s were approximately 80% lower than in the 1980s.[10]

Illegal hunting may be one of the causes of the decline in the Canadian population, and a second cause may be the decline in sea ice. Ivory gulls breed near to sea ice and the loss may make it difficult to feed their chicks.[10][11]

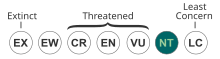

The species is classified by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as "Near Threatened".[1]

Literary appearances

editAn ivory gull is the inspiration for the eponymous carving in Holling C. Holling's classic Newbery Medal-winning children's book, Seabird.

References

edit- ^ a b c d BirdLife International (2018). "Pagophila eburnea". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T22694473A132555020. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22694473A132555020.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Mallory, Mark L.; Stenhouse, Iain J.; Gilchrist, Grant; Robertson, J., Gregory; Haney, Christopher; Macdonald, Stewart D. (2008). "Ivory Gull: Systematics". The Birds of North America Online. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 2010-11-16.(subscription required)

- ^ Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 143, 288. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Mallory, Mark L.; Stenhouse, Iain J.; Gilchrist, Grant; Robertson, J., Gregory; Haney, Christopher; Macdonald, Stewart D. (2008). "Ivory Gull: Distribution". The Birds of North America Online. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 2010-11-18. (subscription required)

- ^ Pons, J.-M.; Hassanin, A.; Crochet, P.-A. (2005). "Phylogenetic relationships within the Laridae (Charadriiformes: Aves) inferred from mitochondrial markers" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 37 (3): 686–699. Bibcode:2005MolPE..37..686P. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.05.011. PMID 16054399. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-09. Retrieved 2014-11-22.

- ^ McAtee, W. L. (1951). "Bird Names Connected with Weather, Seasons, and Hours". American Speech. 26 (4): 268–278. doi:10.2307/453005. JSTOR 453005.

- ^ "Ivory Gull Identification, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology". www.allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved 2020-09-25.

- ^ Volkov, Andrej E.; Korte, Jacobus De (1966). "Distribution and numbers of breeding ivory gulls Pagophila eburnea in Severnaja Zemlja, Russian Arctic" (PDF). Polar Research. 15: 11–21. doi:10.1111/j.1751-8369.1996.tb00455.x (inactive 1 November 2024).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Gilg, Olivier; Boertmann, David; Merkel, Flemming (2009). "Status of the endangered Ivory Gull, Pagophila eburnea, in Greenland" (PDF). Polar Biology. 32 (9): 1275–1286. Bibcode:2009PoBio..32.1275G. doi:10.1007/s00300-009-0623-4. S2CID 45579610.

- ^ a b c "Beautiful ivory gulls are disappearing from the Arctic". New Scientist (3091): 14. 17 September 2016.

- ^ Gilchrist, H. Grant; Mallory, Mark L. (2005). "Declines in abundance and distribution of the ivory gull (Pagophila eburnea) in Arctic Canada". Biological Conservation. 121 (2): 303–309. Bibcode:2005BCons.121..303G. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2004.04.021.

Further reading

edit- Blomqvist, Sven; Elander, Magnus (1981). "Sabine's Gull (Xema sabini), Ross's Gull (Rhodostethia rosea) and Ivory Gull (Pagophila eburnea) Gulls in the Arctic: A Review". Arctic. 34 (2): 122–132. doi:10.14430/arctic2513. JSTOR 40509127.

- Bull, John; Farrand Jr., John (April 1984). The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Birds, Eastern Region. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-41405-8.

- Gilg, Olivier; Strøm, Hallvard; Aebischer, Adrian; Gavrilo, Maria V.; Volkov, Andrei E.; Miljeteig, Cecilie; Sabard, Brigitte (2010). "Post-breeding movements of northeast Atlantic ivory gull Pagophila eburnea populations". Journal of Avian Biology. 41 (5): 532–542. doi:10.1111/j.1600-048X.2010.05125.x.

- Harrison, Peter (1991). Seabirds: an identification guide (2nd ed.). London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 978-071363510-2.

- Mallory, Mark L.; Gilchrist, H. Grant; Fontaine, Alain J.; Akearok, Jason A. (2003). "Local ecological knowledge of Ivory Gull declines in arctic Canada". Arctic. 56 (3): 293–298. doi:10.14430/arctic625. JSTOR 40512546.

- Renaud, Wayne E.; McLaren, Peter L. (1982). "Ivory Gull (Pagophila eburnea) distribution in late summer and autumn in eastern Lancaster Sound and western Baffin Bay". Arctic. 35 (1): 141–148. doi:10.14430/arctic2314. JSTOR 40509309.

- Stenhouse, Iain J.; Gilchrist, Grant; Mallory, Mark L.; Robertson, Gregory J. (2006). COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Ivory Gull Pagophila eburnea in Canada (PDF). Ottawa, Canada: Committee on the status of endangered wildlife in Canada. ISBN 978-0-662-43267-8.

External links

edit- Video and audio recordings of the Ivory Gull Archived 2019-04-03 at the Wayback Machine, Macaulay Library, Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Ivory Gull in California Ivory Gull information and Photos in California

- Satellite tracking of Greenland Ivory Gulls

- Oiseaux Photos, illustrations, map.

- FGBOW Photos on Flickr

- Avibase