Obadiah (/oʊbəˈdaɪ.ə/; Hebrew: עֹבַדְיָה – ʿŌḇaḏyā or עֹבַדְיָהוּ – ʿŌḇaḏyāhū; "servant or slave of Yah"), also known as Abdias,[2] is a biblical prophet. The authorship of the Book of Obadiah is traditionally attributed to the prophet Obadiah.

Obadiah | |

|---|---|

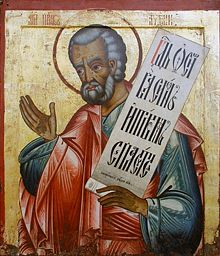

Obadiah in a Russian icon (first quarter of the 18th century) | |

| Prophet | |

| Died | Unknown |

| Venerated in | Judaism Christianity Islam |

| Feast | 19 November (Catholic, Lutheran, and Eastern Orthodox churches) 15 Tobi (Coptic) |

| Attributes | Prophet with his index finger of his right hand pointing upward[1] |

| Major works | Book of Obadiah |

The majority of scholars date the Book of Obadiah to shortly after the fall of Jerusalem in 587 BC.[3] As part of the recent Persian turn in Minor Prophets scholarship, the Book of Obadiah is considered to have been shaped by the conflicts between Yehud and the Edomites in the fifth and fourth centuries BCE and to have evolved through a process of redaction.[4][5]

Biblical account

editDating

editThe composition date is disputed and difficult to determine due to the lack of information regarding the prophet Obadiah. However, because Obadiah wrote about Edom, there are two generally accepted dates. The first is 853–841 BC, when Jerusalem was invaded by Philistines and Arabs during the reign of Jehoram of Judah (recorded in 2 Kings 8:20–22 and 2 Chronicles 21:8-17). This earlier period would place Obadiah as a contemporary of the prophet Elijah. Jewish traditions favor the earlier date because the Jewish Talmud identifies Obadiah as an Edomite himself, and a descendant of Eliphaz the Temanite,[6] the first of the friends of Job to speak with him about his tribulations.[7]

The other is 607–586 BCE, when Jerusalem was attacked by Nebuchadnezzar II of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, which led to the Babylonian captivity (recorded in Psalm 137). The later date would place Obadiah as a contemporary of the prophet Jeremiah. The Interpreters' Bible states that:

The political situation implied in the prophecy points to a time after the Exile, probably in the mid-fifth century B.C. No value can be attributed to traditions identifying this prophet with King Ahab's steward (... so Babylonian Talmud, Sanhedrin 39b) or with King Ahaziah's captain (... so Pseudo-Epiphanius...).

- — The Interpreters' Bible.[8]

Rabbinic tradition

editAccording to the Talmud, Obadiah is said to have been a convert to Judaism from Edom,[9] a descendant of Eliphaz, the friend of Job. He is identified with the Obadiah who was the servant of Ahab, and was chosen to prophesy against Edom because he was himself an Edomite.

Obadiah is supposed to have received the gift of prophecy for having hidden the "hundred prophets"[10] from the persecution of Jezebel.[9] He hid the prophets in two caves, so that if those in one cave should be discovered those in the other might yet escape.[11]

Obadiah was very rich, but all his wealth was expended in feeding the poor prophets, until, in order to be able to continue to support them, finally he had to borrow money at interest from Ahab's son Jehoram.[12] Obadiah's fear of God was one degree higher than that of Abraham; and if the house of Ahab had been capable of being blessed, it would have been blessed for Obadiah's sake.[9]

Christian tradition

editIn some Christian traditions he is said to have been born in "Sychem" (Shechem), and to have been the third captain sent out by Ahaziah against Elijah.[13][14] The date of his ministry is unclear due to certain historical ambiguities in the book bearing his name, but is believed to be around 586 B.C.

He is regarded as a saint by several Eastern churches. His feast day is celebrated on the 15th day of the Coptic Month Tobi (23/24 January) in the Coptic Orthodox Church. The Eastern Orthodox Church and those Eastern Catholic Churches which follow the Byzantine Rite celebrate his memory on 19 November. (For those churches which follow the traditional Julian Calendar, 19 November currently falls on 2 December of the modern Gregorian Calendar.)

He is celebrated on 28 February in the Syriac and Malankara Churches, and with the other Minor prophets in the Calendar of saints of the Armenian Apostolic Church on 31 July.

According to an old tradition, Obadiah is buried in Sebastia, at the same site as Elisha and where later the body of John the Baptist was believed to have been buried by his followers.[15]

Islamic tradition

editSome Islamic scholars identify the prophet Dhu al-Kifl with Obadiah.[16]

See also

editReferences

editCitations

edit- ^ Stracke, Richard (2015-10-20). "The Prophet Obadiah". Christian Iconography.

- ^ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Abdias". www.newadvent.org. Retrieved 2023-01-01.

- ^ Riding, Charles Bruce. “Dating Obadiah to 801 BC”. Reformed Theological Review 80, no. 3 (December 1, 2021): 189–217. Accessed January 7, 2025. https://rtrjournal.org/index.php/RTR/article/view/286

- ^ Becking, Bob (2021). Julia M. O'Brien (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of the Minor Prophets. Oxford University Press. pp. 437–448. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190673208.013.28.

The constant quarrels between the Persian province Yehud and the Edomites in the fifth and fourth centuries BCE should hence be seen as the delivery room for the traditions leading to the book of Obadiah. This book articulates and ventilates the way in which the inhabitants of Jerusalem and surroundings found a way to cope with the Edomite threat. Not a single event but a string of events stands at the background of this biblical book. This also indicates that Obadiah in its present form is the final product of a process of redaction and rewriting.

- ^ Ben Zvi, Ehud. 1996. A Historical-Critical Study of the book of Obadiah. BZAW 242. Berlin: de Gruyter.

- ^ Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Obadiah". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

- ^ Job 4:1

- ^ The Interpreter's Bible, 1953, Volume VI, pp. 857–859, John A. Thompson

- ^ a b c "Tract Sanhedrin, Volume VIII, XVI, Part II (Haggada), Chapter XI", The Babylonian Talmud, Boston: The Talmud Society, p. 376 Translated by Michael L. Rodkinson

- ^ 1 Kings 18:4

- ^ 1 Kings 18:3–4

- ^ Midrash Exodus Rabbah xxxi. 3

- ^ 2 Kings 1

- ^ compilation and translation by Holy Apostles Convent. (1998), The Lives of the Holy Prophets, Buena Vista CO: Holy Apostles Convent, p. 4, ISBN 0-944359-12-4

- ^ Denys Pringle, The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: A Corpus. Vol. 2: L-Z (excluding Tyre), p. 283.

- ^ Quran 38:48

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Hirsch, Emil G.; Ochser, Schulim (1905). "Obadiah". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. Vol. 9. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. p. 369.

- Holweck, F. G., A Biographical Dictionary of the Saints. St. Louis, MO: B. Herder Book Co., 1924.

External links

edit- Prophet Obadiah (Abdias) Orthodox icon and synaxarion