The Early Cyrillic alphabet, also called classical Cyrillic or paleo-Cyrillic, is an alphabetic writing system that was developed in Medieval Bulgaria in the Preslav Literary School during the late 9th century. It is used to write the Church Slavonic language, and was historically used for its ancestor, Old Church Slavonic. It was also used for other languages, but between the 18th and 20th centuries was mostly replaced by the modern Cyrillic script, which is used for some Slavic languages (such as Russian), and for East European and Asian languages that have experienced a great amount of Russian cultural influence.

| Early Cyrillic alphabet Словѣньска азъбоукꙑ | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | |

Time period | From c. 893 in Bulgaria[1] |

| Direction | Varies |

| Languages | Old Church Slavonic, Church Slavonic, old versions of many Slavic languages |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | Egyptian hieroglyphs[2]

|

Child systems | Cyrillic script |

Sister systems | Latin alphabet Coptic alphabet Armenian alphabet |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Cyrs (221), Cyrillic (Old Church Slavonic variant) |

| Unicode | |

| |

History

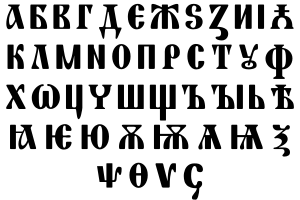

editThe earliest form of manuscript Cyrillic, known as ustav, was based on Greek uncial script, augmented by ligatures and by letters from the Glagolitic alphabet for consonants not found in Greek.[3]

The Glagolitic script was created by the Byzantine monk Saint Cyril, possibly with the aid of his brother Saint Methodius, around 863.[3] Most scholars agree that Cyrillic, on the other hand, was created by Cyril's students at the Preslav Literary School in the 890s as a more suitable script for church books, based on uncial Greek but retaining some Glagolitic letters for sounds not present in Greek.[4][5][6][7] At the time, the Preslav Literary School was the most important early literary and cultural center of the First Bulgarian Empire and of all Slavs:[6]

The earliest Cyrillic texts are found in northeastern Bulgaria, in the vicinity of Preslav—the Krepcha inscription, dating back to 921,[8] and a ceramic vase from Preslav, dating back to 931.[6] Moreover, unlike the other literary centre in the First Bulgarian Empire, the Ohrid Literary School, which continued to use well into the 12th century, the School at Preslav was using Cyrillic in the early 900s.[9] The systematization of Cyrillic may have been undertaken at the Council of Preslav in 893, when the Old Church Slavonic or Glagolitic Cyrillic liturgy was adopted by the First Bulgarian Empire.[1]

Unlike the Churchmen in Ohrid, Preslav scholars were much more dependent upon Greek models and quickly abandoned the Glagolitic scripts in favor of an adaptation of the Greek uncial to the needs of Slavic, which is now known as the Cyrillic alphabet.

The earliest Cyrillic texts are found in northeastern Bulgaria, in the vicinity of Preslav—the Krepcha inscription, dating back to 921,[10] and a ceramic vase from Preslav, dating back to 931.[6] Moreover, unlike the other literary centre in the First Bulgarian Empire, the Ohrid Literary School, which continued to use Glagolitic well into the 12th century, the School at Preslav was using Cyrillic in the early 900s.[11] The systematization of Cyrillic may have been undertaken at the Council of Preslav in 893, when the Old Church Slavonic liturgy was adopted by the First Bulgarian Empire.[1]

American scholar Horace Lunt has alternatively suggested that Cyrillics emerged in the border regions of Greek proselytization to the Slavs before it was codified and adapted by some systematizer among the Slavs. The oldest Cyrillic manuscripts look very similar to 9th and 10th century Greek uncial manuscripts,[3] and the majority of uncial Cyrillic letters were identical to their Greek uncial counterparts.[1]

The early Cyrillic alphabet was very well suited for the writing of Old Church Slavic, generally following a principle of "one letter for one significant sound", with some arbitrary or phonotactically-based exceptions.[3] Particularly, this principle is violated by certain vowel letters, which represent [j] plus the vowel if they are not preceded by a consonant.[3] It is also violated by a significant failure to distinguish between /ji/ and /jĭ/ orthographically.[3] There was no distinction of capital and lowercase letters, though manuscript letters were rendered larger for emphasis, or in various decorative initial and nameplate forms.[4] Letters served as numerals as well as phonetic signs; the values of the numerals were directly borrowed from their Greek-letter analogues.[3] Letters without Greek equivalents mostly had no numeral values, whereas one letter, koppa, had only a numeric value with no phonetic value.[3]

Since its creation, the Cyrillic script has adapted to changes in spoken language and developed regional variations to suit the features of national languages. It has been the subject of academic reforms and political decrees. Variations of the Cyrillic script are used to write languages throughout Eastern Europe and Asia.

The form of the Russian alphabet underwent a change when Tsar Peter the Great introduced the civil script (Russian: гражданский шрифт, romanized: graždanskiy šrift, or гражданка, graždanka), in contrast to the prevailing church typeface, (Russian: церковнославя́нский шрифт, romanized: cerkovnoslavjanskiy šrift) in 1708. (The two forms are sometimes distinguished as paleo-Cyrillic and neo-Cyrillic.) Some letters and breathing marks which were used only for historical reasons were dropped. Medieval letterforms used in typesetting were harmonized with Latin typesetting practices, exchanging medieval forms for Baroque ones, and skipping the western European Renaissance developments. The reform subsequently influenced Cyrillic orthographies for most other languages. Today, the early orthography and typesetting standards remain in use only in Slavonic. A comprehensive repertoire of early Cyrillic characters has been included in the Unicode standard since version 5.1, published April 4, 2008. These characters and their distinctive letterforms are represented in specialized computer fonts for Slavistics.

-

View of the cave monastery near the village of Krepcha, Opaka Municipality in Bulgaria. Here is the oldest Cyrillic inscription dated of 921.[12]

-

The Cyrillic alphabet on birch bark document № 591 from ancient Novgorod (Russia). Dated to 1025–1050 AD.

Alphabet

edit| Image | Unicode | Name (Cyrillic) |

Name (translit.) |

Translit. international system[3][14] | Translit. ALA-LC[15] | IPA | Numeric value | Origin | Meaning of name | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| А а | азъ | azо̆ | a | a | [ɑː] | 1 | Greek alpha Α | I (First-person personal pronoun) | |||

| Б б | боукꙑ | buky | b | b | [b] | Greek beta in Thera form | letters | ||||

| В в | вѣдѣ | vědě | v | v | [v] | 2 | Greek Beta Β | know | |||

| Г г | глаголи | glagoli | g | g | [ɡ][3] | 3 | Greek Gamma Γ | talk | When marked with a palatalization mark, this letter is pronounced [ɟ]; this occurs only rarely, and only in borrowings.[3] | ||

| Д д | добро | dobro | d | d | [d̪] | 4 | Greek Delta Δ | good | |||

| Є є | єсть | est’ | e | e | [ɛ̠] | 5 | Greek Epsilon Ε | is - exists | |||

| Ж ж | живѣтє | živěte | ž | zh | [ʒ] | Glagolitic Zhivete Ⰶ | live | ||||

| Ѕ ѕ | ѕѣло | dzělo | d︠z︡ | ż | [d̪z̪] | 6 | Greek Stigma Ϛ | very | The form ꙃ had the phonetic value [dz] and no numeral value, whereas the form ѕ was used only as a numeral and had no phonetic value.[3] Since the 12th century, ѕ came to be used instead of ꙃ.[16][17] In many manuscripts з is used instead, suggesting lenition had taken place.[3] | ||

| З з, Ꙁ ꙁ | зємл҄ꙗ | zemlja | z | z | [z̪] ~ [z] | 7 | Greek Zeta Ζ | earth | The first form developed into the second. | ||

| И и | ижє | iže | i | и=i, й=ĭ | [iː] ~ [e] | 8 | Greek Eta Η | ||||

| І і | и | i | ī | [i] ~ [j] | 10 | Greek Iota Ι | and | ||||

| К к | како | kako | k | k | [k] | 20 | Greek Kappa Κ | as | When marked with a palatalization mark, this letter is pronounced [c]; this occurs only rarely, and only in borrowings.[3] | ||

| Л л | людїѥ | ljudjije | l | l | [l]; sometimes [ʎ][3] | 30 | Greek Lambda Λ | people | When marked with a palatalization mark or followed by a palatalizing vowel (ю, ѭ, or ꙗ, and sometimes ѣ), this letter is pronounced [ʎ]; some manuscripts do not mark palatalization, in which case it must be inferred from context.[3] | ||

| М м | мꙑслитє | myslite | m | m | [m] | 40 | Greek Mu Μ | think | |||

| Н н | нашь | našĕ | n | n | [n]; sometimes [ɲ][3] | 50 | Greek Nu Ν | ours | When marked with a palatalization mark or followed by a palatalizing vowel (ю, ѭ, or ꙗ, and sometimes ѣ), this letter is pronounced [ɲ]; some manuscripts do not mark palatalization, in which case it must be inferred from context.[3] | ||

| О о | онъ | onо̆ | o | o | [o] | 70 | Greek Omicron Ο | he/it | |||

| П п | покои | pokoj | p | p | [p] | 80 | Greek Pi Π | peace/rest[18] | |||

| Р р | рьци | rĕci | r | r | [r]; sometimes [rʲ][3] | 100 | Greek Rho Ρ | say | When marked with a palatalization mark or followed by a palatalizing vowel (ю or ѭ), this letter is pronounced [rʲ]; some manuscripts do not mark palatalization, in which case it must be inferred from context.[3] This palatalization was lost rather early in South Slavic speech.[3] | ||

| С с | слово | slovo | s | s | [s] | 200 | Greek lunate Sigma Ϲ | word/speech | |||

| Т т | тврьдо | tvĕrdo | t | t | [t] | 300 | Greek Tau Τ | hard/surely | |||

| Оу оу | оукъ | ukо̆ | u | оу=u, ꙋ=ū | [u] | 400 | Greek Omicron-Upsilon ΟΥ / Ꙋ | learning | The first form developed into the second, a vertical ligature. A less common alternative form was a digraph with izhitsa: Оѵ оѵ. | ||

| Ф ф | фрьтъ | fĕrtо̆ | f | f | [f] or possibly [p][3] | 500 | Greek Phi Φ | This letter was not needed for Slavic but used to transcribe Greek Φ and Latin ph and f.[3] It was probably, but not certainly, pronounced as [f] rather than [p]; however, in some cases it has been found as a transcription of Greek π.[3] | |||

| Х х | хѣръ | xěrо̆ | ch/x | kh | [x] | 600 | Greek Chi Χ | When marked with a palatalization mark, this letter is pronounced [ç]; this occurs only rarely, and only in borrowings.[3] | |||

| Ѡ ѡ | ѡтъ | ōtо̆ | ō | ѡ=ō, ѿ=ō͡t | [o] | 800 | Greek Omega ω | from | This letter was rarely used, mostly appearing in the interjection "oh", in the preposition ‹otŭ›, in Greek transcription, and as a decorative capital.[3] | ||

| Ц ц | ци | ci | c | t͡s | [ts] | 900 | Glagolitic Tsi Ⱌ | See also: Ꙡ ꙡ. | |||

| Ч ч | чрьвь | čĕrvĕ | č | ch | [tʃ] | 90 | Glagolitic Cherv Ⱍ | worm | This letter replaced koppa as the numeral for 90 after about 1300.[3] | ||

| Ш ш | ша | ša | š | sh | [ʃ] | Glagolitic Sha Ⱎ | |||||

| Щ щ | ща | šta | št | sht | [ʃt] | Glagolitic Shta Ⱋ | This letter varied in pronunciation from region to region; it may have originally represented the reflexes of [tʲ].[3] It was sometimes replaced by the digraph шт.[3] Pronounced [ʃtʃ] in Old East Slavic. Later analyzed as a Ш-Т ligature by folk etymology, but neither the Cyrillic nor the Glagolitic glyph originated as such a ligature.[3] | ||||

| Ъ ъ | ѥръ | jerо̆ | ŏ/ŭ | ″ | [ŏ] or [ŭ][3] | Glagolitic Yer Ⱏ[1] | After č, š, ž, c, dz, št, and žd, this letter was pronounced identically to ь instead of its normal pronunciation.[3] | ||||

| Ꙑ ꙑ | ѥрꙑ | jery | y | ы=ȳ, ꙑ=y, | [ɯ] or [ɯji] or [ɯjĭ][3] | Ъ + І ligature. | Ꙑ was the more common form; rarely, a third form, ы, appears.[3] | ||||

| Ь ь | ѥрь | jerĕ | ĕ/ĭ | ' | [ĭ] or [ɪ][3] | Glagolitic Yerj Ⱐ[1] | |||||

| Ѣ ѣ | ѣть | ětĕ | ě | ě | [æ][3] | Glagolitic yat Ⱑ[1] | In western South Slavic dialects of Old Church Slavonic, this letter had a more closed pronunciation, perhaps [ɛ] or [e].[3] This letter was written only after a consonant; in all other positions, ꙗ was used instead.[3] An exceptional document is Pages of Undolski, where ѣ is used instead of ꙗ. | ||||

| Ꙗ ꙗ | ꙗ | ja | ja | i͡a | [jæː] | І-А ligature | This letter was probably not present in the original Cyrillic alphabet.[1] | ||||

| Ѥ ѥ | ѥ | je | je | i͡e | [jɛ] | І-Є ligature | This letter was probably not present in the original Cyrillic alphabet.[1] | ||||

| Ю ю | ю | ju | ju | i͡u | [ju] | І-ОУ ligature, dropping У | There was no [jo] sound in early Slavic, so І-ОУ did not need to be distinguished from І-О. After č, š, ž, c, dz, št, and žd, this letter was pronounced [u], without iotation. | ||||

| Ѫ ѫ | ѫсъ | ǫsо̆ | ǫ | ǫ | [ɔ̃] | Glagolitic Ons Ⱘ | Called юсъ большой (big yus) in Russian. | ||||

| Ѭ ѭ | ѭсъ | jǫsо̆ | jǫ | i͡ǫ | [jɔ̃] | І-Ѫ ligature | After č, š, ž, c, dz, št, and žd, this letter was pronounced [ɔ̃], without iotation. Called юсъ большой йотированный (iotated big yus) in Russian. | ||||

| Ѧ ѧ | ѧнъ | jęnŏ | ę | ę | [ɛ̃] | 900 | Glagolitic Ens Ⱔ | Pronounced [jɛ̃] when not preceded by a consonant.[3] Called юсъ малый (little yus) in Russian. | |||

| Ѩ ѩ | ѩсъ | jęsо̆ | ję | i͡ę | [jɛ̃] | І-Ѧ ligature | This letter does not exist in the oldest (South Slavic) Cyrillic manuscripts, but only in East Slavic ones.[3] It was probably not present in the original Cyrillic alphabet.[1] Called юсъ малый йотированный (iotated little yus) in Russian. | ||||

| Ѯ ѯ | ѯи | ksi | ks | k͡s | [ks] | 60 | Greek Xi Ξ | xi (letter name) | These two letters were not needed for Slavic but were used to transcribe Greek and as numerals. | ||

| Ѱ ѱ | ѱи | psi | ps | p͡s | [ps] | 700 | Greek Psi Ψ | psi (letter name) | |||

| Ѳ ѳ | ѳита | fita | t/f/th/ph | ḟ | [t], or [f], or possibly [θ] | 9 | Greek Theta Θ | theta (letter name) | This letter was not needed for Slavic but was used to transcribe Greek and as a numeral. It seems to have been generally pronounced [t], as the oldest texts sometimes replace instances of it with т.[3] Normal Old Church Slavonic pronunciation probably did not have a phone [θ].[3] | ||

| Ѵ ѵ | ижица | ižica | y/ü | ѷ=ẏ, ѵ=v̇ | [i], [y], [v] | 400 | Greek Upsilon Υ | small yoke/Izhe | This letter was used to transcribe Greek upsilon and as a numeral. It also formed part of the digraph оѵ. | ||

| Ҁ ҁ | ҁоппа | qopa | — | none | 90 | Greek Koppa Ϙ | koppa (letter name) | This letter had no phonetic value, and was used only as a numeral. After about 1300, it was replaced as a numeral by črĭvĭ.[3] |

In addition to the basic letters, there were a number of scribal variations, combining ligatures, and regionalisms used, all of which varied over time.

Sometimes the Greek letters that were used in Cyrillic mainly for their numeric value are transcribed with the corresponding Greek letters for accuracy: ѳ = θ, ѯ = ξ, ѱ = ψ, ѵ = υ, and ѡ = ω.[14]

Numerals, diacritics and punctuation

editEach letter had a numeric value also, inherited from the corresponding Greek letter. A titlo over a sequence of letters indicated their use as a number; usually this was accompanied by a dot on either side of the letter.[3] In numerals, the ones place was to the left of the tens place, the reverse of the order used in modern Arabic numerals.[3] Thousands are formed using a special symbol, ҂ (U+0482), which was attached to the lower left corner of the numeral.[3] Many fonts display this symbol incorrectly as being in line with the letters instead of subscripted below and to the left of them.

Titlos were also used to form abbreviations, especially of nomina sacra; this was done by writing the first and last letter of the abbreviated word along with the word's grammatical endings, then placing a titlo above it.[3] Later manuscripts made increasing use of a different style of abbreviation, in which some of the left-out letters were superscripted above the abbreviation and covered with a pokrytie diacritic.[3]

Several diacritics, adopted from Polytonic Greek orthography, were also used, but were seemingly redundant[3] (these may not appear correctly in all web browsers; they are supposed to be directly above the letter, not off to its upper right):

- ӓ trema, diaeresis (U+0308)

- а̀ varia (grave accent), indicating stress on the last syllable (U+0300)

- а́ oksia (acute accent), indicating a stressed syllable (Unicode U+0301)

- а҃ titlo, indicating abbreviations, or letters used as numerals (U+0483)

- а҄ kamora (circumflex accent), indicating palatalization[citation needed] (U+0484); in later Church Slavonic, it disambiguates plurals from homophonous singulars.

- а҅ dasia or dasy pneuma, rough breathing mark (U+0485)

- а҆ psili, zvatel'tse, or psilon pneuma, soft breathing mark (U+0486). Signals a word-initial vowel, at least in later Church Slavonic.

- а҆̀ Combined zvatel'tse and varia is called apostrof.

- а҆́ Combined zvatel'tse and oksia is called iso.

- д꙽, д̾ Yerok or payerok (U+A67D, U+033E), indicating an omitted 'jerŭ' (ъ) after a letter.[19]

Punctuation systems in early Cyrillic manuscripts were primitive: there was no space between words and no upper and lower case, and punctuation marks were used inconsistently in all manuscripts.[3]

- · ano teleia (U+0387), a middle dot used to separate phrases, words, or parts of words[3]

- . Full stop, used in the same way[3]

- ։ Armenian full stop (U+0589), resembling a colon, used in the same way[3]

- ჻ Georgian paragraph separator (U+10FB), used to mark off larger divisions

- ⁖ triangular colon (U+2056, added in Unicode 4.1), used to mark off larger divisions

- ⁘ diamond colon (U+2058, added in Unicode 4.1), used to mark off larger divisions

- ⁙ quintuple colon (U+2059, added in Unicode 4.1), used to mark off larger divisions

- ; Greek question mark (U+037E), similar to a semicolon

Some of these marks are also used in Glagolitic script.

Used only in modern texts

- , comma (U+002C)

- . full stop (U+002E)

- ! exclamation mark (U+0021)

Gallery

editOld Bulgarian examples

edit- Pictures of Old Bulgarian manuscripts and inscriptions

-

Bulgar translation of Manasses chronicle

Early Cyrillic manuscripts

edit- Pictures of Old Church Slavonic weekly gospels (aprakos)

-

-

Andronikov Gospels

See also

editMedia related to Early Cyrillic at Wikimedia Commons

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Auty, R. Handbook of Old Church Slavonic, Part II: Texts and Glossary. 1977.

- ^ Himelfarb, Elizabeth J. "First Alphabet Found in Egypt", Archaeology 53, Issue 1 (Jan./Feb. 2000): 21.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba Lunt, Horace Gray (2001). Old Church Slavonic Grammar. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-016284-9.

- ^ a b Cubberley 1994

- ^ Dvornik, Francis (1956). The Slavs: Their Early History and Civilization. Boston: American Academy of Arts and Sciences. p. 179.

The Psalter and the Book of Prophets were adapted or „modernized" with special regard to their use in Bulgarian churches, and it was in this school that glagolitic writing was replaced by the so-called Cyrillic writing, which was more akin to the Greek uncial, simplified matters considerably and is still used by the Orthodox Slavs.

- ^ a b c d Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 221–222. ISBN 978-0-521-81539-0.

- ^ Hussey, J. M.; Louth, Andrew (2010). The Orthodox Church in the Byzantine Empire. Oxford History of the Christian Church. Oxford University Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-19-161488-0.

- ^ Провежда се международна конференция в гр. Опака за св. Антоний от Крепчанския манастир. Добротолюбие – Център за християнски, църковно-исторически и богословски изследвания, 15.10.2021.

- ^ Steven Runciman, A history of the First Bulgarian Empire, Appendix IX – The Cyrillic and Glagolitic alphabets, (G. Bell & Sons, London 1930)

- ^ Провежда се международна конференция в гр. Опака за св. Антоний от Крепчанския манастир. Добротолюбие – Център за християнски, църковно-исторически и богословски изследвания, 15.10.2021.

- ^ Steven Runciman, A history of the First Bulgarian Empire, Appendix IX – The Cyrillic and Glagolitic alphabets, (G. Bell & Sons, London 1930)

- ^ Провежда се международна конференция в гр. Опака за св. Антоний от Крепчанския манастир. Добротолюбие – Център за християнски, църковно-исторически и богословски изследвания, 15.10.2021.

- ^ Карадаков, Ангел. "Провежда се международна конференция в гр. Опака за св. Антоний от Крепчанския манастир". Добротолюбие (in Bulgarian). Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ^ a b Matthews, W. K. (1952). "The Latinisation of Cyrillic Characters". The Slavonic and East European Review. 30 (75): 531–548. ISSN 0037-6795. JSTOR 4204350.

- ^ "Church Slavic (ALA-LC Romanization Tables)" (PDF). The Library of Congress. 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2020.

- ^ Памятники Старославянскаго языка / Е. Ѳ. Карскій. — СПб. : Типографія Императорской Академіи наукъ, 1904. — Т. I, с. 14. — Репринт

- ^ "Simonov" (PDF) (in Russian). Retrieved August 11, 2023.

- ^ https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/%D0%BF%D0%BE%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%B8#Old_Church_Slavonic

- ^ Berdnikov and Lapko 2003, p. 12

Sources

edit- Berdnikov, Alexander and Olga Lapko, "Old Slavonic and Church Slavonic in TEX and Unicode" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 5, 2003., EuroTEX '99 Proceedings, September 1999

- Birnbaum, David J., "Unicode for Slavic Medievalists" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 3, 2004., September 28, 2002

- Cubberley, Paul (1996) "The Slavic Alphabets". In Daniels and Bright, below.

- Daniels, Peter T., and William Bright, eds. (1996). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507993-0.

- Everson, Michael and Ralph Cleminson, ""Final proposal for encoding the Glagolitic script in the UCS", Expert Contribution to the ISO N2610R" (PDF)., September 4, 2003

- Franklin, Simon. 2002. Writing, Society and Culture in Early Rus, c. 950–1300. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-511-03025-8.

- Iliev, I. Short History of the Cyrillic Alphabet. Plovdiv. 2012/Иван Г. Илиев. Кратка история на кирилската азбука. Пловдив. 2012. Short History of the Cyrillic Alphabet

- Lev, V., "The history of the Ukrainian script (paleography)", in Ukraine: a concise encyclopædia, volume 1. University of Toronto Press, 1963, 1970, 1982. ISBN 0-8020-3105-6

- Simovyc, V., and J. B. Rudnyckyj, "The history of Ukrainian orthography", in Ukraine: a concise encyclopædia, volume 1 (op cit).

- Zamora, J., Help me learn Church Slavonic

- Azbuka, Church Slavonic calligraphy and typography.

- Obshtezhitie.net, Cyrillic and Glagolitic manuscripts and early printed books.

External links

edit- Old Cyrillic [Стара Славянска Език] text entry application

- Slavonic Computing Initiative

- churchslavonic – Typesetting documents in Church Slavonic language using Unicode

- fonts-churchslavonic – Fonts for typesetting in Church Slavonic language

- Church Slavonic Typography in Unicode (Unicode Technical Note no. 41), 2015-11-04, accessed 2023-01-04.