The Reichskommissariat Ukraine (RKU; lit. 'Reich Commissariat of Ukraine') was established by Nazi Germany in 1941 during World War II. It was the civilian occupation regime of much of German-occupied Ukraine (it also included adjacent areas of the Byelorussian SSR, Russian SFSR, and pre-war Poland). It was governed by the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories headed by Alfred Rosenberg. Between September 1941 and August 1944, the Reichskommissariat was administered by Erich Koch as the Reichskommissar. The administration's tasks included the pacification of the region and the exploitation, for German benefit, of its resources and people. Adolf Hitler issued a Führer decree defining the administration of the newly-occupied Eastern territories on 17 July 1941.[2]

Reichskommissariat Ukraine | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1941–1944 | |||||||||||

| Anthem: Horst-Wessel-Lied ("The Horst Wessel Song") | |||||||||||

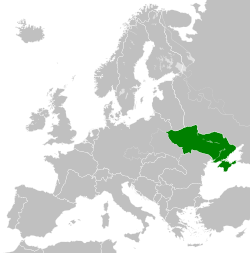

Reichskommissariat Ukraine in 1942 | |||||||||||

| Status | Reichskommissariat of Nazi Germany | ||||||||||

| Capital | Kiev (de jure) Rovno (de facto) | ||||||||||

| Common languages | German (official) | ||||||||||

| Government | Reichskommissariat of Nazi Germany[1] | ||||||||||

| Reichskommissar | |||||||||||

• 1941–1944 | Erich Koch | ||||||||||

| Historical era | World War II | ||||||||||

| 22 June 1941 | |||||||||||

• Established | 20 August 1941 | ||||||||||

• Implement civil administration | 1 September 1941 | ||||||||||

• Remainder part of Generalbezirk Weißruthenien | 25 February 1944 | ||||||||||

• Formal disestablishment | 10 November 1944 | ||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

• Total | 340,000 km2 (130,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

• 1941 | 37,000,000 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Karbovanets | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||

Before the German invasion, Ukraine was a constituent republic of the Soviet Union, inhabited by Ukrainians, Russians, Jewish, Belarusian, Romanian, Polish, and Roma/Gypsy minorities. It was a key subject of Nazi planning for the post-war expansion of the German state. The Nazi extermination policy in Ukraine, with the help of local Ukrainian collaborators,[3] ended the lives of millions of civilians in The Holocaust and other Nazi mass killings: it is estimated 900,000 to 1.6 million Jews and 3[4] to 4[5] million non-Jewish Ukrainians were killed during the occupation; other sources estimate that 5.2 million Ukrainian civilians (of all ethnic groups) perished due to crimes against humanity, war-related disease, and famine amounting to more than 12% of Ukraine's population at the time.[6]

History

editNazi Germany launched Operation Barbarossa against the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941 in breach of the mutual Treaty of Non-Aggression.

On 20 August, Hitler established the Reichskommissariat Ukraine and appointed Erich Koch as Reichskommissar. On the same day, Hitler announced that the region would be under civil administration from noon on 1 September and delineated the boundaries of the region.[7]

Originally subject to Alfred Rosenberg's Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories, it became a separate German civil entity. The first transfer of Soviet Ukrainian territory from military to civil administration took place on 1 September 1941.[8]

In the mind of Adolf Hitler and other German expansionists, the destruction of the USSR, dubbed a "Judeo-Bolshevist" state, would remove a threat from Germany's eastern borders and allow for the colonization of the vast territories of Eastern Europe under the banner of "Lebensraum" (living space) for the fulfilment of the material needs of the Germanic people. Ideological declarations about the German Herrenvolk (master race) having a right to expand their territory especially in the East were widely spread among the German public and Nazi officials of various ranks. Later on, in 1943, Erich Koch said about his mission: "We are a master race, which must remember that the lowliest German worker is racially and biologically a thousand times more valuable than the population here."[9]

On 14 December 1941, Rosenberg discussed with Hitler various administrative issues regarding the Reichskommissariat Ukraine.[10]

On 28 July 1944, the Soviet army occupied the last part of the Reichskommissariat Ukraine, known as Brest. The RKU was liquidated on 10 November 1944.[1]

Geography

editThe Reichskommissariat Ukraine excluded several parts of present-day Ukraine, and included some territories outside of its modern borders. It extended in the west from the Volhynia region around Lutsk, to a line from Vinnytsia to Mykolaiv along the Southern Bug river in the south, to the areas surrounding Kiev, Poltava and Zaporozhye in the east. Conquered territories further to the east, including the rest of Ukraine (Crimea, Chernigov, Kharkov, and the Donets Basin), were under military governance until the German withdrawal 1943–44.[11]

Eastern Galicia was transferred to the control of the General Government following a Hitler decree, becoming its fifth district, (District of Galicia).[citation needed]

It also encompassed several southern parts of today's Belarus, including Polesia, a large area to the north of the Pripyat River with forests and marshes, as well as the city of Brest-Litovsk, and the towns of Pinsk and Mozyr.[12] This was done by the Germans in order to secure a steady wood supply and efficient railroad and water transportation.[12]

Administration

editPolitical figures related to the German administration of Ukraine

edit- Alfred Rosenberg, Reich Minister for the Occupied Eastern Territories

- Georg Leibbrandt, Eastern Ministry

- Otto Bräutigam, Eastern Ministry

- Reichskommissar of Ukraine, Erich Koch

- Alfred Eduard Frauenfeld, Generalkommissar for Generalbezirk Krim-Taurien

- Kurt Klemm, Generalkommissar for Generalbezirk Shitomir (October 1941 – October 1942)

- Ernst Ludwig Leyser, Generalkommissar for Generalbezirk Shitomir (October 1942 – October 1943)

- Helmut Quitzrau, Generalkommissar for Generalbezirk Kiev (September 1941 – February 1942)

- Waldemar Magunia, Generalkommissar for Generalbezirk Kiev (February 1942 – 1944)

- Ewald Oppermann, Generalkommissar for Generalbezirk Nikolajev

- Heinrich Schoene, Generalkommissar for Generalbezirk Wolhynien-Podolien (September 1941 – February 1944)

- Claus Selzner, Generalkommissar for Generalbezirk Dnepropetrowsk (September 1941 – June 1944)

- Karl Stumpp, ethnographer and leader of the SS Sonderkommando Dr Karl Stumpp

Military commanders linked with the German administration of Ukraine

edit- Wehrmachtsbefehlshaber Ukraine (WBU)

- Generalleutnant d.R. Waldemar Henrici (until October 1942)

- General der Flieger Karl Kitzinger (from October 1942)

- Höherer SS- und Polizeiführer Southern Russia (HSSPF Russland-Süd)

- SS-Obergruppenführer Friedrich Jeckeln (June–October 1941)

- SS-Obergruppenführer Hans-Adolf Prützmann (October 1941 – 1944; from October 1943 also Höchster SS- und Polizeiführer (HöSSPF) Ukraine)

- Höherer SS- und Polizeiführer Black Sea (HSSPF Schwarzes Meer)

- SS-Gruppenführer Ludolf-Hermann von Alvensleben (October–December 1943)

- SS-Obergruppenführer Richard Hildebrandt (December 1943 – August 1944)

- SS-Gruppenführer Adolf von Bomhard, head of police

- SS-Gruppenführer Walter Schimana, commander of the SS Division Galicia

- SS-Brigadeführer Fritz Freitag, commander of the SS Division Galicia

Administrative divisions

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2022) |

The administrative capital of the Reichskommissariat was Rovno, and it was divided into six Generalbezirke (general districts), called Generalkommissariate (general commissariats) in the pre-Barbarossa planning. This administrative structure was in turn subdivided into 114 Kreisgebiete, and further into 443 Parteien.[citation needed]

Each Generalbezirk was administered by a Generalkommissar; each Kreisgebiete "circular [i.e., district] area" was led by a Gebietskommissar and each Partei "party" was governed by a Ukrainian or German "Parteien Chef" (Party Chief). At the level below were German or Ukrainian Akademiker ("Academics" – i.e., District Chiefs) (similar to Polish "Wojts" in the General Government). At the same time at a smaller scale, the local Municipalities were administered by native "Bailiffs" and "Mayors", accompanied by respective German political advisers if needed. In the most important areas, or where a German Army detachment remained, the local administration was always led by a German; in less significant areas local personnel was in charge.[citation needed]

The six general districts were (English names and administrative centres in parentheses):

- Shitomir (Zhytomyr) – headed by Regierungpräsident Kurt Klemm, then by SS-Brigadeführer Ernst Ludwig Leyser (from 1942)

- Kiew (Kiev) – headed by SA-Brigadeführer Helmut Quitzrau (till February 14, 1942), then SA-Oberführer Waldemar Magunia (from February 14, 1942)

- Nikolajew (Nikolayev) – headed by NSFK-Obergruppenführer Ewald Oppermann

- Wolhynien und Podolien (Volhynia and Podolia; Luzk) – headed by SA Obergruppenführer Heinrich Schoene

- Dnjepropetrowsk (Dnepropetrovsk) – headed by Oberbefehlshaber der NSDAP ('party commander in chief') Claus Selzner

- Krym-Taurien (Crimea-Taurida; Melitopol) – headed by Gauleiter Alfred Frauenfeld

Scheduled for incorporation into the Reichskommissariat Ukraine but never transferred to civil administration were the Generalkommissariate Tschernigow (Chernigov), Charkow (Kharkov), Stalino (Donetsk), Woronezh (Voronezh), Rostow (Rostov-on-Don), Stalingrad, and Saratow (Saratov), which would have brought the boundary of the province to the western border of Kazakhstan.[13] In addition, Reichskommissar Koch had wishes of further extending his Reichskommissariat to Ciscaucasia.[14]

Krym-Taurien

editThe administrative position of the Krim Generalbezirk remained ambiguous.[citation needed] According to the original German plan it was to correspond approximately to the old Taurida Governorate (therefore including also mainland portions of Ukraine), and was to consist of two Teilbezirke (sub-districts):[citation needed]

- Taurien (the mainland sections, including parts of the Nikolayev and Zaporozhye provinces.)

- Krym (the Crimean peninsula)

Only the first of these saw transfer to civil administration in September 1942, with the peninsula remaining under military control for the duration of the war.[15] Its administrator, Frauenfeld, played off the military and civil authorities against each other and gained the freedom to run the territory as he saw fit. He thereby enjoyed complete autonomy, verging on independence, from Koch's authority. Frauenfeld's administration was much more moderate than Koch's and consequentially more economically successful. Koch was greatly angered by Fraunfeld's insubordination (a comparable situation also existed in the administrative relationship between the Estonian general commissariat and Reichskommissariat Ostland).[citation needed]

The district's title was a misnomer, it only included the area north of the Crimean peninsula up to the Dnieper river.[15]

Demographics

editThe official German press, in 1941, reported the Ukrainian urban and rural populations as 19 million each. During the commissariat's existence the Germans only undertook one official census, for January 1, 1943, documenting a population of 16,910,008 people.[16] The 1926 Soviet official census recorded the urban population as 5,373,553 and the rural population as 23,669,381 – a total of 29,042,934, however the borders of the administrative region of the Soviet Ukrainian SSR were noticeably different from those of the Reichskommissariat. In 1939, a new census reported the Ukrainian urban population as 11,195,620 and rural population as 19,764,601 – a total of 30,960,221. The Ukrainian Soviets counted 17% of total Soviet population, and a significant portion was also separately occupied by Romania.[citation needed]

Security

editThe Wehrmacht came under pressure for political reasons to gradually restore private property in zones under military control and to accept local volunteer recruits into their units and into the Waffen-SS, as promoted by local Ukrainian nationalist organizations, the OUN-B and the OUN-M, whilst receiving political support from the Wehrmacht.[citation needed]

The German Reichsführer-SS and chief of German Police, Heinrich Himmler, initially had direct authority over any SS formations in Ukraine to order "Security Operations", but soon lost it – especially after the summer of 1942 when he tried to regain control over policing in Ukraine by gaining authority for the collection of the harvest, and failed miserably, in large part because Koch withheld cooperation. In Ukraine, Himmler soon became the voice of relative moderation, hoping that an improvement in the Ukrainians' living conditions would encourage greater numbers of them to join the Waffen-SS's foreign divisions. Koch, appropriately nicknamed the "hangman of Ukraine", was contemptuous of Himmler's efforts. In this matter Koch had the support of Hitler, who remained skeptical when not hostile to the idea of recruiting Slavs in general and Soviet nationals in particular into the Wehrmacht.[citation needed]

| Sleeve badges of battalions of the so-called «Ukrainian Hilfspolizei» in the German Ordnungspolizei of the Reichskommissariat Ukraine[17] | |||||||

| 106th | 114th | 115th and 118th | Officers' badge | ||||

Economic exploitation

editIn the civil administration of the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories numerous technical staff worked under Georg Leibbrandt, former chief of the east section of the foreign political office in the Nazi Party, now chief of the political section in the Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories. Leibbrandt's deputy, Otto Bräutigam, had previously worked as a consul with experience in the Soviet Union. Economic affairs remained under the direct management of Hermann Göring (the Plenipotentiary of Germany's Four Year Plan). From 21 March 1942 Fritz Sauckel had the role of "General Plenipotentiary for Labour Deployment" (Generalbevollmächtigter für den Arbeitseinsatz), charged with recruiting manpower for Germany throughout Europe, though in Ukraine Koch insisted that Sauckel confine himself to setting requirements, leaving the actual "recruitment" of Ost-Arbeiter to Koch and his brutes. The Todt Organization Ost Branch operated from Kiev. Other members of the German administration in Ukraine included Generalkommissar Leyser and Gebietkommissar Steudel.

The Ministry of Transport had direct control of "Ostbahns" and "Generalverkehrsdirektion Osten" (the railway administration in the eastern territories). These German central government interventions in the affairs of the East Affairs by ministries were known as Sonderverwaltungen (special administrations).

The position of the Eastern Affairs Ministry was weak because its department chiefs: (Economy, Work, Foods & Crops and Forest & Woods) held similar posts in other government departments (The Four-Year Plan, Eastern Economic Office, Foods and Farming Ministry, etc.) with other supplementary junior staff. Thus the East Ministry was managed by personal criteria and particular interests over official orders. Additionally, they failed to maintain the "Political Section" at an equal level with more specialized departments (Economy, Works, Farms, etc.) because political considerations clashed with exploitation plans in the territory.

The Reichskommissariat Ukraine paid occupation taxes and funds to the German Reich until February 1944 in the amount of 1.246 billion ℛ︁ℳ︁ (equivalent to €5 billion 2021) and 107.9 million Rbls, in accord with information composed by Lutz von Krosigk, the Reich Minister of Finances.

The Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories ordered Koch and Hinrich Lohse (the Reichskommissar of Ostland) in March 1942 to supply 380,000 farm workers and 247,000 industrial workers for German work needs. Later Koch was mentioned during the new year message of 1943, how he "recruited" 710,000 workers in Ukraine. This and subsequent "worker registration" drives in Ukraine would eventually backfire after the Battle of Kursk (July–August 1943) when the Germans would attempt to build a defensive line along the Dnieper only to discover that the necessary manpower had been either recruited to forced labour in Germany or had gone underground to forestall such "recruitment".

Alfred Rosenberg implemented an "Agrarian New Order" in Ukraine, ordering the confiscation of Soviet state properties to establish German state properties. Additionally the replacement of Russian[clarification needed] Kolkhozes and Sovkhozes, by their own "Gemeindwirtschaften" (German Communal Farms), the installation of state enterprise "Landbewirstschaftungsgessellschaft Ukraine M.b.H." for managing the new German state farms and cooperatives, and the foundation of numerous "Kombines" (Great German exploitation Monopolies) with government or private capital in the territory, to exploit the resources and Donbas area.

Hitler said "Ukraine and the East lands would produce 7 million, or more likely 10 or 12 million tonnes of grain to provide Germany's food needs".[This quote needs a citation]

German intentions

editAccording to the Nazis, both Jewish and Slavic Ukrainians were untermensch and therefore only fit for enslavement or extermination. Erich Koch, who was chosen by Adolf Hitler to rule Ukraine, made the point about the inferiority of Ukrainians with a certain simplicity: "Even if I find a Ukrainian who is worthy of sitting at my table, I must have him shot"[18] and "remember that the lowliest German worker is racially and biologically a thousand times more valuable than the population here, which is more distinct from Aryan genealogy than Leningrad."[19]

The regime was planning to encourage the settlement of German and other "Germanic" farmers in the region after the war, along with the empowerment of some ethnic Germans in the territory. Ukraine was the furthest eastern settlement of the migrating ancient Goths between the 2nd and 4th centuries and subsequently, according to Hitler, "Only German should be spoken here".[20]

In Ukraine, the Germans published a local journal in the German language, the Deutsche Ukrainezeitung.[citation needed]

During the occupation a very small number of cities and their accompanying districts maintained German names. These cities were designated as urban strongholds for Volksdeutsche natives.[21] Hegewald (Himmler's field headquarters and the location of a small, experimental German colony),[22] Försterstadt (also a Volksdeutsche colony),[23] Halbstadt (a Low German Mennonite settlement),[21] Alexanderstadt,[24] Kronau[21] and Friesendorf[25] were some of these.

On 12 August 1941, Hitler ordered the complete destruction of the Ukrainian capital of Kiev by the use of incendiary bombs and gunfire.[26] Because the German military lacked sufficient material for this operation it wasn't carried out, after which the Nazi planners instead decided to starve the city's inhabitants. Heinrich Himmler on the other hand considered Kiev to be "an ancient German city" because of the Magdeburg city rights that it had acquired centuries prior.[26]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "Reichskommissariat Ukraine". www.encyclopediaofukraine.com. Retrieved 2020-03-03.

A German colony, the RKU constituted an important part of Adolf Hitler's Lebensraum and was completely deprived of autonomy or international status. Nazi plans called for the postwar unification of the RKU with the territory of the German Reich; most Ukrainians (considered unfit for Germanization) were to be resettled beyond the Urals to make room for German colonists. In fact Hitler was unable to inspire many Germans to colonize Ukraine. Despite ambitious plans only a few villages were cleared of their Ukrainian inhabitants and populated with Germans (both groups were resettled under duress). Those experiments were profoundly resented by the local population, which saw them as portents of German postwar intentions. Resettlement was also prevented by the German retreat and then by the formal liquidation of the RKU on 10 November 1944.

- ^ "Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression". Decree of the Fuehrer concerning the administration of the newly-occupied Eastern territories. The Avalon Project at Yale Law School. 1996–2007. Retrieved 2007-10-04.

- ^ Alfred J. Rieber (2003). "Civil Wars in the Soviet Union" (PDF). pp. 133, 145–147. Slavica Publishers.

- ^ Magocsi, Paul Robert (1996). A History of Ukraine. University of Toronto Press. p. 633. ISBN 9780802078209.

- ^ Michael Berenbaum (ed.), A Mosaic of Victims: Non-Jews Persecuted and Murdered by the Nazis, New York University Press, 1990; ISBN 1-85043-251-1

- ^ Vadim Erlikman. Poteri narodonaseleniia v XX veke: spravochnik. Moscow, 2004. ISBN 5-93165-107-1. pp. 21–35.

- ^ Führer-Erlasse" 1939–1945.

- ^ Berkhoff, p. 36.

- ^ The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. William Shirer. 2011. p. 939. ISBN 978-1-4516-5168-3.

- ^ "Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression". About Discussions [of Rosenberg] with the Fuehrer on 14 December 1941. The Avalon Project at Yale Law School. 1996–2007. Retrieved 2007-10-04.

- ^ Berkhoff, pp. 299ff.

- ^ a b Berkhoff, Karel C. (2004). Harvest of despair: life and death in Ukraine under Nazi rule, p. 37. President and Fellows of Harvard College.

- ^ Dallin, Alexander (1958). Deutschen Herrschaft in Russland 1941–1945, p. 67 (in German). Droste.

- ^ Kroener, Müller & Umbreit (2003) Germany and the Second World War V/II, p. 50

- ^ a b Berkhoff, p. 39.

- ^ Berkhoff, pp. 36-37.

- ^ Музичук С. країнські військові нарукавні емблеми під час Другої світової війни 1939-45 рр. // Знак, 2004. — ч. 33. — с. 9 – 11.

- ^ "Timothy Snyder Quote: 'Erich Koch, chosen by Hitler to rule Ukraine, made the point about the inferiority of Ukrainians with a certain simplici... '".

- ^ Shirer, William Lawrence (1990). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany. Fawcett Crest. ISBN 0449219771.

- ^ Wendy Lower, Nazi Empire-Building and the Holocaust in Ukraine, p. 161

- ^ a b c Lower, p. 267.

- ^ Lower, Wendy: Nazi empire-building and the Holocaust in Ukraine, pp. 162–181. University of North Carolina Press, 2005. [1]

- ^ Lower 2005, p. 197.

- ^ Jehke, Rolf: Territoriale Veränderungen in Deutschland und deutsch verwalteten Gebieten 1874–1945. 23 February 2010. (In German). Retrieved 10 August 2010. [2]

- ^ Rolf Jehke. "Generalbezirk Dnjepropetrowsk". Territorial.de. Archived from the original on 2017-12-04. Retrieved 2014-06-03.

- ^ a b Berkhoff, pp. 164–165.

Further reading

edit- Toynbee, Arnold; Toynbee, Veronica; et al. (1954), "Ukraine, under German Occupation, 1941–44", Hitler's Europe, London: Oxford University Press, pp. 316–337.

- Berkhoff, Karel C. (2004), Harvest of Despair: Life and Death in Ukraine Under Nazi Rule, Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press, ISBN 0-674-01313-1.

- Rich, Norman (1974), Hitler's War Aims: The Establishment of the New Order, New York: W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 0-393-05509-4.

External links

edit- Officials of the Ostministerium and the Reichskommissariats at the Wayback Machine (archived October 29, 2009)

- Map of Occupied Europe Archived 2012-12-05 at archive.today