Yakima (/ˈjækɪmɑː/ or /ˈjækɪmə/) is a city in, and the county seat of, Yakima County, Washington, United States, and the state's 11th most populous city. As of the 2020 census, the city had a total population of 96,968 and a metropolitan population of 256,728.[4] The unincorporated suburban areas of West Valley and Terrace Heights are considered a part of greater Yakima.[7]

Yakima, Washington | |

|---|---|

Yakima as viewed from Lookout Point | |

| Nickname(s): The Palm Springs of Washington; The Heart of Central Washington | |

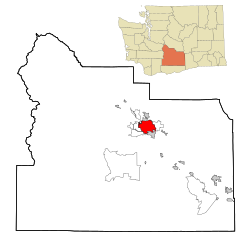

Location of Yakima in Yakima County | |

| Coordinates: 46°36′07″N 120°30′21″W / 46.60194°N 120.50583°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Washington |

| County | Yakima |

| Incorporated | December 10, 1883 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–manager |

| • Body | City council |

| • Mayor | Patricia Byers[1] |

| • City manager | Vacant[1] |

| Area | |

• City | 28.32 sq mi (73.35 km2) |

| • Land | 27.86 sq mi (72.16 km2) |

| • Water | 0.46 sq mi (1.19 km2) 1.84% |

| Elevation | 1,070 ft (326 m) |

| Population | |

• City | 96,968 |

• Estimate (2023)[5] | 96,750 |

| • Rank | US: 350th WA: 11th |

| • Density | 3,473.0/sq mi (1,341.0/km2) |

| • Urban | 133,145 (US: 257th) |

| • Metro | 256,643 (US: 193rd) |

| Demonym | Yakimanian[6] |

| Time zone | UTC–8 (Pacific (PST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC–7 (PDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 98901–98904, 98907–98909 |

| Area code | 509 |

| FIPS code | 53-80010 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1509643[3] |

| Website | yakimawa.gov |

Yakima is about 60 miles (100 kilometers) southeast of Mount Rainier in Washington. It is situated in the Yakima Valley, a productive agricultural region noted for apple, wine, and hop production. As of 2011, the Yakima Valley produces 77% of all hops grown in the United States.[8] The name Yakima originates from the Yakama Nation Native American tribe, whose reservation is located south of the city.

History

editThe Yakama people were the first known inhabitants of the Yakima Valley. In 1805, the Lewis and Clark Expedition came to the area and encountered abundant wildlife and rich soil, prompting the settlement of homesteaders.[9] A Catholic Mission was established in Ahtanum, southwest of present-day Yakima, in 1847.[10] The arrival of settlers and their conflicts with the natives resulted in the Yakima War. The U.S. Army established Fort Simcoe in 1856 near present-day White Swan as a response to the uprising. The Yakamas were defeated and forced to relocate to the Yakama Indian Reservation.[11][12]

Yakima County was created in 1865. When bypassed by the Northern Pacific Railroad in December 1884, over 100 buildings were moved with rollers and horse teams to the nearby site of the depot. The new city was dubbed North Yakima and was officially incorporated and named the county seat on January 27, 1886. The name was changed to Yakima in 1918. Union Gap was the new name given to the original site of Yakima.[13]

On May 18, 1980, the eruption of Mount St. Helens caused a large amount of volcanic ash to fall on the Yakima area. Visibility was reduced to near-zero conditions that afternoon, and the ash overloaded the city's wastewater treatment plant.[13][14]

Geography

editAccording to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 28.32 square miles (73.35 km2), of which 27.86 square miles (72.16 km2) is land and 0.46 square miles (1.19 km2), or 1.84% is water.[2] Yakima is 1,095 feet above mean sea level.

The city of Yakima is located in the Upper Valley of Yakima County. The county is geographically divided by Ahtanum Ridge and Rattlesnake Ridge into two regions: the Upper (northern) and Lower (southern) valleys. Yakima is located in the more urbanized Upper Valley, and is the central city of the Yakima Metropolitan Statistical Area.

The unincorporated suburban areas of West Valley and Terrace Heights are considered a part of greater Yakima. Other nearby cities include Moxee, Tieton, Cowiche, Wiley City, Tampico, Gleed, and Naches in the Upper Valley, as well as Wapato, Toppenish, Zillah, Harrah, White Swan, Parker, Buena, Outlook, Granger, Mabton, Sunnyside, and Grandview in the Lower Valley.

Bodies of water

editThe Yakima River runs through the city from its source at Lake Keechelus in the Cascade Range to the Columbia River at Richland. It is the primary irrigation source for the Yakima Valley and also used for both fishing and recreation. The Naches River, a tributary of the Yakima River, forms the northern border of the city.

The Yakima Greenway is a 20-mile (32 km) system of parks, paved pathways, and nature reserves along the Yakima and Naches rivers.[15] The community project was formed in 1983 with work to reclaim a former city landfill into a park, which opened in 1990 as Sarg Hubbard Park.[16]

Several small lakes flank the northern edge of the city, including Myron Lake, Lake Aspen, Bergland Lake (private) and Rotary Lake (also known as Freeway Lake). These lakes are popular with fishermen and swimmers during the summer.

Climate

editYakima has a cold semi-arid climate (Köppen BSk) with a Mediterranean precipitation pattern. Winters are cold, with December the coolest month, with a mean temperature of 28.5 °F (−1.9 °C).[17] Annual average snowfall is 21.6 in (55 cm),[17] with most occurring in December and January, when the snow depth averages 2 to 3 in (5.1 to 7.6 cm). There are 18.9 days per year in which the high does not surpass freezing, and 1.6 mornings where the low is 0 °F (−18 °C) or lower.[17] Springtime warming is very gradual, with the average last freeze of the season May 13. Summer days are hot, but the diurnal temperature variation is large, averaging 34.9 °F (19.4 °C) in July, sometimes reaching as high as 50 °F (27.8 °C) during that season; there are 40.2 afternoons of maxima reaching 90 °F (32 °C) or greater annually and 5.7 afternoons of 100 °F (38 °C) maxima. Autumn cooling is very rapid, with the average first freeze of the season occurring on September 30. Due to the city's location in a rain shadow, precipitation, at an average of 8.01 in (203 mm) annually, is low year-round,[17] but especially during summer. Extreme temperatures have ranged from −25 °F (−32 °C) on February 1, 1950,[a] to 113 °F (45 °C) on June 29, 2021.[19]

| Climate data for Yakima Airport, Washington (1991–2020 normals,[b] extremes 1946–present[c]) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 68 (20) |

70 (21) |

80 (27) |

92 (33) |

102 (39) |

113 (45) |

109 (43) |

110 (43) |

100 (38) |

91 (33) |

73 (23) |

72 (22) |

113 (45) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 56.3 (13.5) |

59.1 (15.1) |

70.0 (21.1) |

79.7 (26.5) |

89.9 (32.2) |

95.8 (35.4) |

101.5 (38.6) |

100.3 (37.9) |

92.1 (33.4) |

78.3 (25.7) |

64.9 (18.3) |

54.4 (12.4) |

102.9 (39.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 39.5 (4.2) |

47.2 (8.4) |

56.6 (13.7) |

64.7 (18.2) |

74.1 (23.4) |

80.7 (27.1) |

89.9 (32.2) |

88.5 (31.4) |

79.4 (26.3) |

64.4 (18.0) |

48.9 (9.4) |

38.2 (3.4) |

64.3 (17.9) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 31.7 (−0.2) |

36.6 (2.6) |

43.4 (6.3) |

49.9 (9.9) |

58.8 (14.9) |

65.1 (18.4) |

72.4 (22.4) |

70.9 (21.6) |

62.2 (16.8) |

49.8 (9.9) |

38.0 (3.3) |

30.6 (−0.8) |

50.8 (10.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 24.0 (−4.4) |

26.1 (−3.3) |

30.2 (−1.0) |

35.2 (1.8) |

43.5 (6.4) |

49.5 (9.7) |

55.0 (12.8) |

53.3 (11.8) |

44.9 (7.2) |

35.3 (1.8) |

27.2 (−2.7) |

23.1 (−4.9) |

37.3 (2.9) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 7.4 (−13.7) |

11.4 (−11.4) |

19.7 (−6.8) |

23.9 (−4.5) |

30.2 (−1.0) |

36.8 (2.7) |

43.8 (6.6) |

42.3 (5.7) |

33.8 (1.0) |

21.3 (−5.9) |

13.2 (−10.4) |

8.1 (−13.3) |

0.5 (−17.5) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −21 (−29) |

−25 (−32) |

−1 (−18) |

18 (−8) |

25 (−4) |

30 (−1) |

34 (1) |

35 (2) |

24 (−4) |

4 (−16) |

−13 (−25) |

−17 (−27) |

−25 (−32) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.19 (30) |

0.81 (21) |

0.64 (16) |

0.55 (14) |

0.74 (19) |

0.50 (13) |

0.20 (5.1) |

0.21 (5.3) |

0.23 (5.8) |

0.64 (16) |

0.86 (22) |

1.44 (37) |

8.01 (203) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 6.2 (16) |

2.7 (6.9) |

0.6 (1.5) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

3.0 (7.6) |

7.7 (20) |

20.3 (52) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.5 | 7.3 | 6.6 | 5.6 | 6.3 | 4.6 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 3.0 | 5.9 | 8.3 | 10.3 | 71.8 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 4.4 | 2.0 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.5 | 5.5 | 14.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 77.7 | 72.7 | 60.6 | 51.6 | 48.2 | 46.8 | 44.3 | 48.2 | 55.6 | 63.4 | 74.5 | 79.8 | 60.3 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 22.8 (−5.1) |

27.3 (−2.6) |

28.8 (−1.8) |

30.9 (−0.6) |

36.7 (2.6) |

42.6 (5.9) |

46.0 (7.8) |

46.9 (8.3) |

42.3 (5.7) |

35.1 (1.7) |

30.0 (−1.1) |

23.9 (−4.5) |

34.4 (1.4) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 64 | 113 | 186 | 210 | 279 | 300 | 341 | 310 | 240 | 186 | 60 | 62 | 2,351 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 2 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 22 | 38 | 50 | 51 | 60 | 63 | 71 | 71 | 64 | 55 | 21 | 23 | 49 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Source 1: NOAA (relative humidity, and dew point 1961–1990)[17][19][20][18] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas (sun and uv)[21] | |||||||||||||

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

See or edit raw graph data.

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1890 | 1,535 | — | |

| 1900 | 3,154 | 105.5% | |

| 1910 | 14,082 | 346.5% | |

| 1920 | 18,539 | 31.7% | |

| 1930 | 22,101 | 19.2% | |

| 1940 | 27,221 | 23.2% | |

| 1950 | 38,486 | 41.4% | |

| 1960 | 43,284 | 12.5% | |

| 1970 | 45,588 | 5.3% | |

| 1980 | 49,826 | 9.3% | |

| 1990 | 54,827 | 10.0% | |

| 2000 | 71,845 | 31.0% | |

| 2010 | 91,067 | 26.8% | |

| 2020 | 96,968 | 6.5% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 96,750 | [5] | −0.2% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[22] 2020 Census[4] | |||

2020 census

edit| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[23] | Pop 2010[24] | Pop 2020[25] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 42,928 | 47,523 | 42,212 | 59.75% | 52.18% | 43.53% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 1,308 | 1,311 | 1,184 | 1.82% | 1.44% | 1.22% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 1,116 | 1,311 | 1,321 | 1.55% | 1.44% | 1.36% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 792 | 1,286 | 1,342 | 1.10% | 1.41% | 1.38% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 48 | 46 | 126 | 0.07% | 0.05% | 0.13% |

| Other race alone (NH) | 60 | 125 | 414 | 0.08% | 0.14% | 0.43% |

| Mixed Race or Multi-Racial (NH) | 1,380 | 1,878 | 3,377 | 1.92% | 2.06% | 3.48% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 24,213 | 37,587 | 46,992 | 33.70% | 41.27% | 48.46% |

| Total | 71,845 | 91,067 | 96,968 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

As of the 2020 census, there were 96,968 people, 35,752 households, 22,858 families residing in the city.[26] The population density was 3,487.4 inhabitants per square mile (1,346.5/km2). There were 37,192 housing units at an average density of 1,286.0 inhabitants per square mile (496.5/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 51.80% (50,234) White, 1.45% (1,405) African American, 2.53% (2,453) Native American, 1.46% (1,418) Asian, 0.18% (171) Pacific Islander, 27.66% (26,824) from some other races and 14.92% (14,463) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 45.46% (42,947) of the population.[27]

Of the 35,752 households, 32.6% had children under the age of 18; 42.8% were married couples living together; 31.1% had a female householder with no husband present. Of all households, 29.1% consisted of individuals and 14.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.7 and the average family size was 3.4.

27.3% of the population was under the age of 18, 9.8% from 18 to 24, 25.5% from 25 to 44, 19.6% from 45 to 64, and 14.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 33.6 years. For every 100 females, the population had 96.0 males. For every 100 females ages 18 and older, there were 95.7 males.

The 2018–2022 five-year American Community Survey estimates show that the median household income was $55,734 (with a margin of error of +/- $7,514) and the median family income $57,296 (+/- $3,722). Males had a median income of $31,188 (+/- $828) versus $26,018 (+/- $1,183) for females. The median income for those above 16 years old was $28,697 (+/- $1,619). Approximately, 14.7% of families and 19.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 27.4% of those under the age of 18 and 10.0% of those ages 65 or over.

2010 census

editAs of the 2010 census, there were 91,067 people with 33,074 households, and 21,411 families residing in the city. The population density was 3,350.6 inhabitants per square mile (1,293.7/km2). There were 34,829 housing units at an average density of 1,281.4 inhabitants per square mile (494.8/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 67.1% (61,065) White, 1.7% (1,556) African American, 2.0% (1,838) Native American, 1.5% (1,347) Asian, 0.1% (83) Pacific Islander, 23.3% (21,216) from some other races and 4.4% (3,962) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 41.3% (37,587) of the population.[28][29] 19.1% of the population had a bachelor's degree or higher.[30]

There were 33,074 households, of which 33.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 44.7% were married couples living together, 15.7% had a female householder with no husband present, 6.3% had a male householder with no wife present, and 35.3% were non-families. 28.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.68 and the average family size was 3.3.

People under the age of 18 accounted for 28.3% of the population, while 13.1% were 65 years or older. The median age was 33.9 years, and 50.7% of the population was female.

The median household income was $39,706. The per capita income was $20,771. 21.3% of the population were below the poverty line.

Economy

editYakima's growth in the 20th century was fueled primarily by agriculture. The Yakima Valley produces many fruit crops, including apples, peaches, pears, cherries, and melons. Many vegetables are also produced, including peppers, corn and beans. Most of the nation's hops, a key ingredient in the production of beer, are also grown in the Yakima Valley. Many of the city's residents have come to the valley out of economic necessity and to participate in the picking, processing, marketing and support services for the agricultural economy.

Top employers

editAccording to the City's 2022 Annual Comprehensive Financial Report,[31] the largest employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | Industry | # of Employees | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yakima Valley Memorial Hospital | Health Care | 2,500 | 1.9% |

| 2 | Walmart (Yakima/Sunnyside/Grandview) |

Department store | 1,700 | 1.3% |

| 3 | Yakima School District, No. 7 | Education | 1,594 | 1.2% |

| 4 | Zirkle Fruit | Fruit processing | 1,500 | 1.1% |

| 5 | Washington Fruit & Produce | Fruit processing | 1,500 | 1.1% |

| 6 | Yakama Nation Government Operations |

Government | 1,289 | 1.0% |

| 7 | Borton Fruit | Fruit processing | 1,212 | 0.9% |

| 8 | Astria Health (Yakima/Sunnyside/Toppenish) |

Health Care | 1,200 | 0.9% |

| 9 | Yakama Nation Enterprises (Utility, C-Store, Credit Enterprise, Forest Products, Legends Casino) |

Enterprise | 1,170 | 0.9% |

| 10 | Yakima County | County Government | 1,074 | 0.8% |

| — | Total employers | — | 14,739 | 11.1% |

Downtown Yakima, long the retail hub of the region, has undergone many changes since the late 1990s. Three major department stores, and an entire shopping mall that is now closed, have been replaced by a Whirlpool Corporation facility (shut down in 2011), an Adaptis call center, and several hotels. The region's retail core has shifted to the town of Union Gap to a renovated shopping mall and other new retail businesses. The Downtown Futures Initiative promotes the downtown area as a center for events, services, entertainment, and small, personal shopping experiences.[32] The DFI has provided for street-to-storefront remodeling along Yakima Avenue throughout the entire downtown core, and includes new pedestrian-friendly lighting, water fountains, planters, banner poles, new trees and hanging baskets, and paver-inlaid sidewalks.

Events held downtown include Yakima Downtown New Year's Eve, a Cinco de Mayo celebration, Yakima Live music festival, Yakima Summer Kickoff Party, Fresh Hop Ale Fest,[33] a weekly Farmers' Market,[34] and the Hot Shots 3-on-3 Basketball Tournament.[35]

Over ninety wineries are in the Yakima Valley.[36]

The Yakima Training Center, between Yakima and Ellensburg, is a United States Army training center. It is used primarily for maneuver training and land warrior system testing, and has a live-fire area. Artillery units from the Canadian Armed Forces based in British Columbia, as well as the Japan Ground Self Defense Force, conduct annual training in Yakima. Japanese soldiers train there because it allows for large-scale live-fire maneuvers not available in Japan. Similarly, it is the closest impact area for the Canadian Gunners, the next closest being in Wainwright, Alberta.

Tourism

editIn the early 2000s, the city of Yakima, in conjunction with multiple city organizations, began revitalization and preservation efforts in its historic downtown area. The Downtown Yakima Futures Initiative was created to make strategic public investments in sidewalks, lighting and landscaping to encourage further development. As a result, local businesses featuring regional produce, wines, and beers, among other products, have returned to the downtown area. Many of these businesses are located on Front Street, Yakima Avenue and 1st Street.

During the summer, a pair of historic trolleys operate along five miles (8 km) of track of the former Yakima Valley Transportation Company through the Yakima Gap connecting Yakima and Selah. The Yakima Valley Trolleys organization, incorporated in 2001, operates the trolleys and a museum for the City of Yakima.

The City of Yakima expanded the Convention Center in 2020.

Arts and culture

editCultural activities and events take place throughout the year. The Yakima Valley Museum houses exhibits related to the region's natural and cultural history, a restored soda fountain, and periodic special exhibitions. Downtown Yakima's historic Capitol Theatre and Seasons Performance Hall, as well as the West-side's Allied Arts Center, present numerous musical and stage productions. Larson Gallery housed at Yakima Valley College present six diverse art exhibitions each year. The city is home to the Yakima Symphony Orchestra. The Yakima Area Arboretum is a botanical garden featuring species of both native and adapted non-native plants. Popular music tours, trade shows, and other large events are hosted at the Yakima SunDome in State Fair Park.

The film The Hanging Tree (1959) was shot entirely in and around Yakima.[37]

Festivals and fairs

edit- Central Washington State Fair, held each year in late September at State Fair Park.

- Yakima Folklife Festival,[38] held the second week of July at Franklin Park.

- Fresh Hop Ale Festival,[33] held each October in Downtown Yakima.

- A Case of the Blues and All That Jazz,[39] held in August in Sarg Hubbard Park.

- Yakima Pride Festival is a celebration of LGBT pride held in June.[40]

Sports

edit- The Yakima Mavericks are a minor league football team in the Pacific Football League and play at Marquette Stadium.

- The Yakima Beetles American Legion baseball team, 3-time World Champions.

- The Yakima Canines of the American West Football Conference.

- The Yakima Valley Pippins are a collegiate wood bat baseball team that play in the West Coast League.

- Former professional teams

- The Yakima Valley Warriors were an indoor football team. Play ended in 2010.

- The Yakima Sun Kings was a Continental Basketball Association franchise that won 5 CBA championships and disbanded in 2008. The team was reinstituted in 2018 as part of the North American Premier Basketball league.

- The Yakima Bears minor league baseball team, moved to Hillsboro, Oregon after the 2011 season.

- The Yakima Reds soccer team played in the USL Premier Development League, disbanded in 2010.

Government

editYakima is one of the ten first class cities, those with a population over 10,000 at the time of reorganization and operating under a home rule charter.

The Yakima City Council operates under the council–manager form of government. The city council has seven members, elected by district and the mayor is elected by the council members.[1] Yakima's city manager serves under the direction of the City Council, and administers and coordinates the delivery of municipal services. The city of Yakima is a full-service city, providing police, fire, water and wastewater treatment, parks, public works, planning, street maintenance, code enforcement, airport and transit to residents.

In 1994 and 2015, the City of Yakima received the All-America City Award, given by the National Civic League. Ten U.S. cities receive this award per year.

The city council was elected at-large until a 2012 lawsuit filed by the American Civil Liberties Union was ruled in the favor of Latino constituents on the grounds of racial discrimination.[41] The council's four district-based and three at-large seat arrangement was also removed in favor of seven districts—of which two have a Latino majority.[1] The city manager position has been vacant since January 2024, when the new city council removed incumbent Bob Harrison.[1] Several attempts were made in the early 2020s to move Yakima to a mayor–council form of government.[1]

The citizens of Yakima are represented in the Washington Senate by Republicans Curtis King in District 14, and Nikki Torres in District 15, and in the Washington House of Representatives by Republicans Chris Corry and Gina Mosbrucker in District 14, and Republicans Bruce Chandler and Bryan Sandlin in District 15.

At the national level, Yakima is part of Washington's US Congressional 4th District, currently represented by Republican Dan Newhouse.

Education

editThe city of Yakima has three K–12 public school districts, several private schools, and three post-secondary schools.

High schools

editPublic schools

editThere are four high schools in the Yakima School District:

- Davis High School, a 4A high school with about 2,100 students

- Eisenhower High School, a 4A high school with about 2,300 students

- Stanton Academy

- Yakima Online High School

Outside the city:

- West Valley High School, in the West Valley School District, is a division 4A school with a student population of around 1,500.

- East Valley High School, just east of Terrace Heights on the city's eastern side, is in the East Valley School District. It is a 2A school with about 1,000 students.

Private schools

edit- La Salle High School in Union Gap is a Catholic high school in the 1A division and enrolls about 200 students.

- Riverside Christian School, near East Valley High School, is a private K–12 Christian school. Riverside Christian is a 1B school with around 400 students in grades K–12.

- Yakima Adventist Christian School

Post-secondary schools

editYakima Valley College (YVC) is one of the oldest community colleges in the state of Washington. Founded in 1928, YVC is a public, four-year institution of higher education, and part of one of the most comprehensive community college systems in the nation. It offers programs in adult basic education, English as a Second Language, lower-division arts and sciences, professional and technical education, transfer degrees to in-state universities, and community services.[42]

Perry Technical Institute is a private, nonprofit school of higher learning located in the city since 1939. Perry students learn trades such as automotive technology, instrumentation, information technology, HVAC, electrical, machining, office administration, medical coding, and legal assistant/paralegal.

Pacific Northwest University of Health Sciences opened in the fall of 2008,[43] and graduated its first class of osteopathic physicians (D.O.) in 2012. The first college on the 42.5-acre (172,000 m2) campus is home to the first medical school approved in the Pacific Northwest in over 60 years, and trains physicians with an osteopathic emphasis. The school's mission is to train primary-care physicians committed to serving rural and underserved communities throughout the Pacific Northwest. It is housed in a state-of-the-art 45,000 sq ft (4,200 m2) facility.[44]

Media

editThe Yakima Herald-Republic is the primary daily newspaper in the area.

According to Arbitron, the Yakima metropolitan area is the 197th largest radio market in the US, serving 196,500 people.[45]

Yakima is part of the U.S.'s 114th largest television viewing market, which includes viewers in Pasco, Richland and Kennewick.[46]

Transportation

editRoads and highways

editInterstate 82 is the main freeway through the Yakima Valley, connecting the region to Ellensburg and the Tri-Cities, with onward connections to Seattle and Oregon. U.S. Route 12 crosses northern Yakima, joining I-82 and U.S. Route 97 along the east side of the city. State Route 24 terminates in Yakima and is the primary means of reaching Moxee City and agricultural areas to the east. State Route 821 terminates in northern Yakima and traverses the Yakima River canyon, providing an alternate route to Ellensburg that bypasses the I-82 summit at Manastash Ridge.

Public transit

editCity-owned Yakima Transit serves Yakima, Selah, West Valley and Terrace Heights, as well as several daily trips to Ellensburg. There are also free intercity bus systems between adjacent Union Gap and nearby Toppenish, Wapato, White Swan, and Ellensburg.[47]

Airport

editYakima is served by the Yakima Air Terminal, a municipal airport located on the southern edge of the city and is used for general aviation and commercial air service. The FAA identifier is YKM. It has two asphalt runways: 9/27 is 7,604 by 150 feet (2,318 x 46 m) and 4/22 is 3,835 by 150 feet (1,169 x 46 m). Yakima Air Terminal is owned and operated by the city.

Yakima is served by one scheduled air carrier (Alaska Airlines) and two non-scheduled carriers (Sun Country Airlines and Xtra Airways). Alaska Airlines provides multiple daily flights to and from Seattle-Tacoma International Airport, Sun Country Airlines provide charter flights to Laughlin, NV and Xtra Airways provide charter flights to Wendover, NV. During World War II the airfield was used by the United States Army Air Forces.

The airport at is home to numerous private aircraft, and is a test site for military jets and Boeing test flights.

Notable people

edit- Oleta Adams, singer[48]

- Jamie Allen, Major League Baseball player[49]

- Colleen Atwood, Academy Award-winning costume designer

- Mario Batali, celebrity chef[50]

- MarJon Beauchamp, professional basketball player for the Milwaukee Bucks

- Wanda E. Brunstetter, author

- Bryan Caraway, mixed martial artist

- Raymond Carver, author, poet and screenwriter

- William Charbonneau, founder of Tree Top Apple Juice

- Beverly Cleary, author

- Harlond Clift, Major League Baseball player

- Cary Conklin, NFL football player

- Alex Deccio, politician. Former member of Washington House of Representatives and Washington State Senate.[51][52]

- Garret Dillahunt, actor[53]

- Dan Doornink, NFL football player

- William O. Douglas, U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice[50]

- Dave Edler, Major League Baseball player, Yakima Mayor

- Mary Jo Estep, teacher, last survivor of the Battle of Kelley Creek

- Gabriel E. Gomez, politician and former Navy SEAL

- Kathryn Gustafson, artist

- Gordon Haines, NASCAR driver

- Scott Hatteberg, Major League Baseball player

- Joe Hipp, professional boxer

- Al Hoptowit, NFL football player

- Myke Horton, professional football player and cast member of American Gladiators

- Damon Huard, NFL football player

- Robert Ivers, actor

- Harry Jefferson, NASCAR driver

- Marshall Kent, professional ten-pin bowler

- Sam Kinison, actor and comedian

- Larry Knechtel, Grammy Award-winning musician[54]

- Cooper Kupp, NFL football player

- Craig Kupp, NFL football player

- Jake Kupp, NFL football player

- Mark Labberton, seminary president

- Donald A. Larson, World War II flying ace

- Robert Lucas Jr., Nobel prize-winning economist

- Paige Mackenzie, professional golfer

- Josh Pearce, Major League Baseball Player

- Kyle MacLachlan, film and television actor

- Debbie Macomber, author

- Phil Mahre, Olympic gold medalist and world champion skier

- Steve Mahre, Olympic silver medalist and world champion skier

- Barbara La Marr, actress and writer

- Mitch Meluskey, Major League Baseball player

- Colleen Miller, actress

- Don Mosebar, NFL football player

- James "Jimmy" Nolan Jr., former host of Uncle Jimmy's Clubhouse[55]

- Arvo Ojala, actor and artist

- Joe Parsons, snowmobiler

- Floyd Paxton, inventor of the Kwik Lok bread clip

- Gary Peacock, Jazz double bassist

- Steve Pelluer, NFL football player

- Jim Pomeroy, professional motocross racer and member of the AMA Motorcycle Hall of Fame[56]

- William Farrand Prosser, U.S. Congressman and mayor of Yakima[57]

- Gary Puckett, singer, 1960s pop artist of Gary Puckett & The Union Gap

- Pete Rademacher, Olympic and professional boxer

- Monte Rawlins, actor

- Jim Rohn, entrepreneur

- Will Sampson, actor and artist[58]

- Kurt Schulz, NFL football player

- Mel Stottlemyre, Major League Baseball player and coach

- Mel Stottlemyre Jr., Major League Baseball player

- Todd Stottlemyre, Major League Baseball player

- Thelma Johnson Streat, artist

- Taylor Stubblefield, football player

- Miesha Tate, mixed martial artist

- Willie Turner, sprinter

- Janet Waldo, actress

- Bob Wells, baseball player

- Christopher Wiehl, actor

- Lis Wiehl, author and legal analyst

- Jon Westling, 8th president of Boston University

- Chief Yowlachie, Native American actor

Sister cities

edit- Morelia, Michoacán, Mexico[59]

- Itayanagi, Aomori, Japan[60]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Low temperature record from February 1, 1950 has been hidden by NOAA[18]

- ^ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.

- ^ For more information, see ThreadEx

- ^ a b c d e f Sundeen, Jasper Kenzo (January 10, 2024). "New Yakima council members open to idea of strong mayor form of government". Yakima Herald-Republic. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ^ a b "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 20, 2024.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Yakima, Washington

- ^ a b c "Explore Census Data". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 5, 2023.

- ^ a b "City and Town Population Totals: 2020-2023". United States Census Bureau. August 20, 2024. Retrieved August 20, 2024.

- ^ Engel, Samina (November 14, 2013). "Museum honors Yakimanians with permanent exhibit". KIMA. Archived from the original on October 20, 2019. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- ^ "State and City Quickfacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on September 22, 2006. Retrieved November 13, 2006.

- ^ "Hop Economics Working Group". Archived from the original on October 19, 2013. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "City of Yakima History". City of Yakima. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved December 28, 2006.

- ^ "St. Joseph's Mission, Ahtanum Valley, Tampico vicinity, Yakima County, WA". Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record. Archived from the original on June 29, 2014. Retrieved January 11, 2007.

- ^ Meyers, Donald W. (June 4, 2017). "It Happened Here: Treaty of 1855 took land, created the Yakama Nation". Yakima Herald-Republic. Archived from the original on February 6, 2020. Retrieved February 6, 2020.

- ^ "Yakama Indian Nation". www.u-s-history.com. Archived from the original on February 6, 2020. Retrieved February 6, 2020.

- ^ a b Kershner, Jim (October 16, 2009). "Yakima — Thumbnail History". HistoryLink. Archived from the original on March 2, 2019. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- ^ "Ash and aftermath of Mount St. Helens: Our readers remember". Yakima Herald-Republic. May 17, 2015. Archived from the original on July 17, 2019. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- ^ Sundeen, Jasper Kenzo (December 15, 2023). "Upgrades planned to Yakima Greenway at 16th Avenue". Yakima Herald-Republic. Retrieved April 24, 2024.

- ^ Meyers, Donald W. (June 23, 2019). "It Happened Here: Greenway Park named for businessman, civic fixture Sarg Hubbard". Yakima Herald-Republic. Retrieved April 23, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e "NOAA NCEI U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on May 5, 2021. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ a b "Comparative Climatic Data For the United States Through 2018" (PDF). NOAA. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 16, 2020.

- ^ a b "NOAA Online Weather Data – NWS Pendleton". National Weather Service. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "WMO Climate Normals for YAKIMA/YAKIMA AIR TERMINAL, WA 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on June 27, 2023. Retrieved June 27, 2023.

- ^ "Monthly weather forecast and climate - Yakima, WA". Archived from the original on March 28, 2020. Retrieved March 28, 2020.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "P004: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Yakima city, Washington". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved February 25, 2024.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Yakima city, Washington". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved February 25, 2024.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Yakima city, Washington". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved February 25, 2024.

- ^ "US Census Bureau, Table P16: Household Type". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 20, 2024.

- ^ "How many people live in Yakima city, Washington". USA Today. Retrieved August 20, 2024.

- ^ "2010 Demographic Profile Data". Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010. US Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

- ^ La Ganga, Maria L. (September 25, 2014) "Yakima Valley Latinos Getting a Voice, With Court's Help" Archived September 26, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Los Angeles Times

- ^ "State & County QuickFacts - Yakima (city), WA". US Census Bureau State & County QuickFacts. United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on September 22, 2006. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

- ^ "City of Yakima 2022 Annual Comprehensive Financial Report" (PDF). August 20, 2024. p. 175.

- ^ "Downtown Futures Initiative". Archived from the original on May 8, 2008. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ^ a b "Fresh Hop Ale Festival". Freshopalefestival.com. Archived from the original on February 18, 2009. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ^ "Farmers' Market". Yakimafarmersmarket.org. Archived from the original on March 4, 2009. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ^ "Hot Shots 3-on-3 Basketball Tournament". Yakimahotshots.org. Archived from the original on February 27, 2009. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ^ "Yakima Valley Wineries - Wine Tasting in Washington State". www.visityakima.com. Retrieved January 29, 2023.

- ^ Maddrey, Joseph (2016). The Quick, the Dead and the Revived: The Many Lives of the Western Film. McFarland. Page 184. ISBN 9781476625492.

- ^ "Yakima Folklife Festival". Yakimafolklife.org. Archived from the original on December 2, 2010. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ^ "A Case of the Blues and All That Jazz". Festivalnet.com. Archived from the original on May 13, 2014. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ Tomas D'Anella (June 6, 2023). "Yakima Pride Festival and Parade set for Saturday". NBC Right Now. Retrieved June 16, 2023.

- ^ Searcey, Dionne; Gebeloff, Robert (November 19, 2019). "The Divide in Yakima Is the Divide in America". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 19, 2019. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ "Yakima Valley Community College Degrees and Certificates". Archived from the original on January 6, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2017.

- ^ "Pacific Northwest University of Health Sciences". Archived from the original on January 25, 2008. Retrieved December 8, 2007.

- ^ "New osteopathic school planned for Yakima". Puget Sound Business Journal. April 14, 2005. Archived from the original on May 23, 2006. Retrieved February 3, 2007.

- ^ "Arbitron Radio Market Rankings: Spring 2012". Arbotron. Archived from the original on October 16, 2010. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

- ^ "Local Television Market Universe Estimates" (PDF). Nielson. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 14, 2019. Retrieved April 14, 2019.

- ^ "Pahto Public Passage". Yakama Nation Tribal Transit. Archived from the original on March 31, 2012. Retrieved January 27, 2012.

- ^ "Oleta Adams Biography". Archived from the original on July 3, 2014. Retrieved July 19, 2012.

- ^ "Jamie Allen Stats". Baseball Almanac. Archived from the original on August 21, 2012. Retrieved July 19, 2012.

- ^ a b Jenkins, Sarah (April 2, 2006). "Their claim is fame - and a link to the Valley". Yakima Herald-Republic. Archived from the original on November 13, 2021. Retrieved July 19, 2012.

- ^ "Former state Sen. Alex Deccio dies at 89". seattletimes.com. October 25, 2011. Archived from the original on September 19, 2021. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

- ^ "Mourners honor Alex Deccio". nbcrightnow.com. November 3, 2011. Archived from the original on September 19, 2021. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)() - ^ Muir, Pat (September 17, 2010). "Outtakes from the Garret Dillahunt interview". Yakima Herald Republic. Retrieved July 19, 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Ward, Leah (August 23, 2009). "Larry Knechtel, a music legend, dies at 69". Yakima Herald Republic. Archived from the original on May 4, 2010. Retrieved July 19, 2012.

- ^ "James Walter Nolan, Jr. (Obituary)". Yakima Herald-Republic. March 24, 2004. Retrieved July 19, 2012.

- ^ "Jim Pomeroy at the Motorcycle Hall of Fame". motorcyclemuseum.org. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved November 29, 2018.

- ^ "Bioguide Search". bioguide.congress.gov. Biographical Directory of the United States Congress (United States Congress). Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ "Creek actor Will Sampson honored with spot on Oklahoma Walk of Fame". Muscogee (Creek) Nation. Archived from the original on March 1, 2012. Retrieved July 19, 2012.

- ^ Bain, Kaitlin (May 19, 2018). "Yakima's mostly forgotten sister cities, explained". Yakima Herald-Republic. Archived from the original on October 29, 2019. Retrieved October 29, 2019.

- ^ "Washington Sister Cities". Lieutenant Governor Cyrus Habib. Archived from the original on September 4, 2020. Retrieved September 9, 2020.