Hazrat Nizamuddin Dargah[1] is the dargah (mausoleum) of the Sufi saint Nizamuddin Auliya (1238–1325 CE). Situated in the Nizamuddin West area of Delhi, the dargah is visited by thousands of pilgrims every week.[2] The site is also known for its evening qawwali devotional music sessions.[3][4]

| Dargah Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya | |

|---|---|

Amir Khusrau's tomb (left), Nizamuddin Dargah (right) and Jamaat Khana Masjid (background) | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Islam |

| District | New Delhi |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | Dargah |

| Location | |

| Location | Amir Khusro Gate, Dargah Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya, Nizamuddin West, New Delhi |

| Country | India |

| Territory | Delhi NCR |

| Geographic coordinates | 28°35′29″N 77°14′31″E / 28.59140°N 77.24197°E |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Sunni Khilji |

| Type | Dargah |

| Style | Islamic Architecture |

| Date established | 1325 |

| Direction of façade | West |

| Website | |

| https://nizamuddinaulia.org/ | |

Architecture

editThe tombs of Amir Khusrau, Nizamuddin's disciple, and Jehan Ara Begum, Shah Jahan's daughter, are located at the entrance to the complex.[5] Ziauddin Barani and Muhammad Shah are also buried here. Overall, the dargah complex has more than 70 graves.[6][7][8]

The complex was renovated and restored by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture around 2010.[9]

Dargah

editNizamuddin's tomb has a white dome. The main structure was built by Muhammad bin Tughluq in 1325, following Nizamuddin's death. Firuz Shah Tughlaq later repaired the structure and suspended four golden cups from the dome's recesses. Nawab Khurshid Jah of Hyderabad’s legendary Paigah Family gifted the marble balustrade that surrounds the grave. The present dome was built by Faridun Khan in 1562. The structure underwent many additions over the years.[10] The dome is about six metres in diameter.[11]

The dargah is surrounded by a marble patio and is covered with intricate jalis (transl. trellis walls).[8] The dargah complex also has a wazookhana (transl. ablution area).[12][13]

Jamat Khana Masjid

editNext to the dargah is the Jamat Khana Masjid. This mosque is built of red sandstone[14] and has three bays. Its stone walls are carved with inscriptions of texts from the Quran. The mosque has arches that have been embellished with lotus buds, in addition to the facade of its dome having ornamental medallions. The structure was built during the reign of Alauddin Khalji by his son Khizr Khan. Completed between 1312 and 1313, Khizr was responsible for the central dome and hall, and was a follower of Nizamuddin. Around 1325, when Muhammad bin Tughlaq took over the reign, he constructed the two adjoining halls, each of which has two domes. The southern hall, chhoti masjid (transl. small mosque) is restricted to women and features a wooden door. The large dome of the mosque features a golden bowl that is suspended from the centre.[15]

Baoli

editAt the back entrance of the complex is a baoli (transl. stepwell), commissioned by Nizamuddin himself[7] and completed in 1321. It is close to the Yamuna river and is always filled. People believe that its waters have magical powers and bathe in it.[9] According to legend, Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq had commissioned the Tughlaqabad Fort at the same time the baoli was being built. Because he forbade all workers from working on the baoli, they would work on it at night. Upon discovering this, the supply of oil was restricted. The masons then lit their lamps with the water of the baoli, after a blessing.[7]

Location

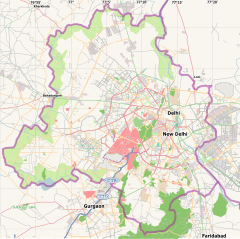

editThe neighborhood surrounding the dargah, Nizamuddin Basti, is named after the saint. The area was initially the site of the settlement of Ghiyaspur, where Nizamuddin lived, and was later named after him.[16] The Basti's population mainly grew after refugees settled here during the Partition of India.[17] Prior to that, the area was mainly occupied only by the pirzade, the direct descendants of Nizamuddin.[18]

The Basti area has small lodges, small eateries and shops selling elements related to Islamic culture, such as religious books, kurtas, skull caps and attar (transl. perfumes). It also has butcher shops.[19]

The area is divided into two parts along Mathura Road: Nizamuddin West where the Dargah complex and a lively market dominated by Muslim vendors is located, and Nizamuddin East, where the Nizamuddin Railway Station is situated.[17]

The area has been a hub for cultural activities in Delhi since the 13th century, leading to many building important buildings in close proximity to the area. This includes Humayun's Tomb and Sunder Nursery, a 16th-century heritage park. The tombs of Mirza Ghalib and Abdul Rahim Khan-I-Khana are also located in this area due to its cultural significance.[19] The other important monuments in the Nizamuddin heritage area include Barakhamba and Lal Mahal.

The dargah complex is immediately surrounded by the Sabz Burj at the intersection of Lodhi Road and Mathura Road, the Urs Mahal (a stage for the qawwalis) and the Chausath Khamba.[8]

Culture

editThe area is referred to as the "nerve centre of Sufi culture in India". On the 17th and 18th day of the Islamic month of Rabi' al-awwal, thousands gather to observe the birth anniversary and urs (death anniversary) of the saint. Besides this, thousands also visit on the birth and death anniversaries of Amir Khusrau, Nizamuddin's disciple. Hundreds visit the dargah everyday throughout the year to pray and pay their respects. The dargah has a tradition of qawwali, especially the one on every Thursday night attracting about 1500 visitors.[19] The regular qawwalis occur every evening after the Maghrib prayer. The dargah has multiple intergenerational darbari qawwals.[20] Women are traditionally not allowed inside the dargah’s inner sanctum.[21] Besides this, the dargah organizes a daily langar.[22]

The evening prayers in which lamps are lit, called the Dua-e-Roshni, is an important ritual. Pilgrims gather around the khadim, the caretaker, who prays for the wishes of all those gathered to be granted.[23]

Death is celebrated in most Sufi orders. As part of the urs, the dargah complex and the tombs are lit up in the tradition of charaghan. Lakhs of people from different religions come from across the world and recite verses in the tradition of fateha. Plates of rose petals and sweets are offered to the tombs and fragrant chaddars (transl. sheets) are draped on them. People tie colourful threads on the jaalis and make vows (mannat) to the saints. Each thread symbolizes a wish.[24]

The festival of Basant Panchami is also celebrated at the dargah. According to legend, Nizamuddin was deeply attached to his nephew, Khwaja Taqiuddin Nuh, who died due to an illness. Nizamuddin grieved over him for a long time. Khusrau, his disciple, wanted to see him smile and dressed up in yellow and began celebrating the onset of Basant, after spotting some women do the same. This caused Auliya to smile, an occasion that is commemorated to this day.[25][26]

In popular culture

edit"Arziyan", a qawwali in the 2009 film Delhi 6 composed by A. R. Rahman is dedicated to Nizamuddin Auliya. "Kun Faya Kun", a song in the 2011 movie Rockstar and again composed by Rahman, is also shot at the dargah, featuring Ranbir Kapoor and Nizami Bandhu, the traditional qawwal of the dargah.[27] The dargah has also been featured in movies like Bajrangi Bhaijaan featuring Salman Khan and Kareena Kapoor, and in "Aawan Akhiyan Jawan Akhiyan" a qawwali in the 2006 film Ahista Ahista featuring Soha Ali Khan and Abhay Deol.[28]

Management

editThe dargah is a property that belongs to the Delhi Waqf Board. Offerings are collected under the baridari system through pirzadas, who are the custodians of the Sufi shrines. This usually comprises descendants of those buried at the dargah. The committee, Anjuman Peerzadan Nizamiyan Khusravi, looks after the dargah.[29]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Livemint (27 January 2024). "Watch | French President Emmanuel Macron at Hazrat Nizamuddin Dargah in Delhi". mint. Retrieved 13 February 2024.

- ^ "Nizamuddin Dargah: Who was Nizamuddin Auliya?". The Times of India. Delhi. 1 April 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ "'Rockstar' music launch at Nizamuddin Dargah". Zee News. 15 September 2011. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- ^ Dasgupta, Piyali (7 January 2014). "799th birthday celebrations of Hazrat Nimazuddin Auliya, held recently at the Hazrat Nizamuddin Dargah in Delhi". The Times of India. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ^ Sharma, Suruchi (29 August 2012). "Rahman returns to Nizamuddin dargah". The Times of India. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ Soofi, Mayank Austen (30 March 2019). "Delhiwale: The dargah's grave arithmetic". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ^ a b c Srinivasan, Sudarshana (22 August 2015). "An afternoon with the saints". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ a b c Ali Khawaja, Saif (5 October 2018). "Walking Through History to Reach Nizamuddin's Dargah". The Citizen. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ^ a b Wajid, Syed (29 March 2020). "Baolis: Water conservation through intermingled traditions and faiths". National Herald. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ^ "Celebrating the mystic tradition". The Hindu. 5 February 2017. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ^ Bakht Ahmed, Firoz (30 July 2011). "Legacy of Hazrat Nizamuddin". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ^ "No new structures at Nizamuddin dargah". The Times of India. Delhi. 20 August 2001. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ^ "ASI seeks action on illegal construction at Nizamuddin". The New Indian Express. 13 June 2019. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ^ Verma, Richi (19 February 2017). "Khilji-era mosque getting a facelift". The Times of India. Delhi. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ^ Sultan, Parvez (21 July 2019). "Restoring an era of pious glory". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ^ Mamgain, Asheesh (8 December 2017). "Nizamuddin Basti: 700 Years of Living Heritage". The Citizen. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ a b Lidhoo, Prerna (10 May 2016). "Once a colony for refugees, now Capital's green heart". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ^ Jeffery, Patricia (2000). Frogs in a Well: Indian Women in Purdah. Manohar. p. 10. ISBN 978-81-7304-300-0.

- ^ a b c Roychowdhury, Adrija (3 April 2020). "Nizamuddin dargah: Sufi central suffers ripples of Jamaat". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ Bhura, Sneha (8 June 2020). "For the qawwals of Nizamuddin Dargah, it's a long wait for a real live performance". The Week. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ "Plea seeks entry of women inside Nizamuddin dargah". The Hindu. 11 December 2018. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ Tankha, Madhur (5 December 2019). "Hazrat Nizamuddin basti celebrates diversity". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ^ Soofi, Mayank Austen (14 March 2017). "Discover Delhi: The Hindu connection to Nizamuddin dargah's evening ritual". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ Anjum, Nawaid (18 June 2020). "While the world is at pause, the world of the Sufis can never end". The Indian Express. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ Safvi, Rana (12 February 2016). "How Delhi's Hazrat Nizamuddin dargah began celebrating Basant Panchami". Scroll.in. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ Shamil, Taimur (3 February 2017). "Celebrating Basant The Sufi Way At Nizamuddin Dargah". HuffPost India. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ Dasgupta, Piyali (24 February 2012). "Ali Zafar visits Nizamuddin Dargah". The Times of India. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- ^ Sood, Samira (26 February 2016). "How to experience qawwali at Hazrat Nizamuddin". Condé Nast Traveller India. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- ^ "Hazrat Nizamuddin Dargah: New board to look into 'mishandling of funds'". The New Indian Express. 17 December 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

Further reading

edit- Dehlvi, Sadia (2012). The Sufi Courtyard: Dargahs of Delhi. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-9350290958.

- Snyder, Michael (2010). "Where Delhi Is Still Quite Far: Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya and the Making of the Nizamuddin Basti" (PDF). Columbia Undergraduate Journal of South Asian Studies. I (2).

- Zuberi, Irfan. "Art, Artists & Patronage: Qawwali in Hazrat Nizamuddin Basti". Academia. Aga Khan Trust for Culture – via academia.edu.

External links

edit- Official website

- Media related to Nizamuddin Dargah at Wikimedia Commons