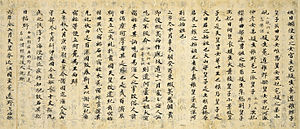

The Nihon Shoki (日本書紀), sometimes translated as The Chronicles of Japan, is the second-oldest book of classical Japanese history. The book is also called the Nihongi (日本紀, "Japanese Chronicles"). It is more elaborate and detailed than the Kojiki, the oldest, and has proven to be an important tool for historians and archaeologists as it includes the most complete extant historical record of ancient Japan. The Nihon Shoki was finished in 720 under the editorial supervision of Prince Toneri with the assistance of Ō no Yasumaro and presented to Empress Genshō.[1] The book is also a reflection of Chinese influence on Japanese civilization.[2] In Japan, the Sinicized court wanted written history that could be compared with the annals of the Chinese.[3]

The Nihon Shoki begins with the Japanese creation myth, explaining the origin of the world and the first seven generations of divine beings (starting with Kuninotokotachi), and goes on with a number of myths as does the Kojiki, but continues its account through to events of the 8th century. It is believed to record accurately the latter reigns of Emperor Tenji, Emperor Tenmu and Empress Jitō. The Nihon Shoki focuses on the merits of the virtuous rulers as well as the errors of the bad rulers. It describes episodes from mythological eras and diplomatic contacts with other countries. The Nihon Shoki was written in classical Chinese, as was common for official documents at that time. The Kojiki, on the other hand, is written in a combination of Chinese and phonetic transcription of Japanese (primarily for names and songs). The Nihon Shoki also contains numerous transliteration notes telling the reader how words were pronounced in Japanese. Collectively, the stories in this book and the Kojiki are referred to as the Kiki stories.[4]

The first translation was completed by William George Aston in 1896 (English).[5]

Chapters

edit- Chapter 01: (First chapter of myths) Kami no Yo no Kami no maki.

- Chapter 02: (Second chapter of myths) Kami no Yo no Shimo no maki.

- Chapter 03: (Emperor Jimmu) Kan'yamato Iwarebiko no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 04:

- (Emperor Suizei) Kamu Nunakawamimi no Sumeramikoto.

- (Emperor Annei) Shikitsuhiko Tamatemi no Sumeramikoto.

- (Emperor Itoku) Ōyamato Hikosukitomo no Sumeramikoto.

- (Emperor Kōshō) Mimatsuhiko Sukitomo no Sumeramikoto.

- (Emperor Kōan) Yamato Tarashihiko Kuni Oshihito no Sumeramikoto.

- (Emperor Kōrei) Ōyamato Nekohiko Futoni no Sumeramikoto.

- (Emperor Kōgen) Ōyamato Nekohiko Kunikuru no Sumeramikoto.

- (Emperor Kaika) Wakayamato Nekohiko Ōbibi no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 05: (Emperor Sujin) Mimaki Iribiko Iniye no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 06: (Emperor Suinin) Ikume Iribiko Isachi no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 07:

- (Emperor Keikō) Ōtarashihiko Oshirowake no Sumeramikoto.

- (Emperor Seimu) Waka Tarashihiko no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 08: (Emperor Chūai) Tarashi Nakatsuhiko no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 09: (Empress Jingū) Okinaga Tarashihime no Mikoto.

- Chapter 10: (Emperor Ōjin) Homuda no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 11: (Emperor Nintoku) Ōsasagi no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 12:

- (Emperor Richū) Izahowake no Sumeramikoto.

- (Emperor Hanzei) Mitsuhawake no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 13:

- (Emperor Ingyō) Oasazuma Wakugo no Sukune no Sumeramikoto.

- (Emperor Ankō) Anaho no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 14: (Emperor Yūryaku) Ōhatsuse no Waka Takeru no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 15:

- (Emperor Seinei) Shiraka no Take Hirokuni Oshi Waka Yamato Neko no Sumeramikoto.

- (Emperor Kenzō) Woke no Sumeramikoto.

- (Emperor Ninken) Oke no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 16: (Emperor Buretsu) Ohatsuse no Waka Sasagi no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 17: (Emperor Keitai) Ōdo no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 18:

- (Emperor Ankan) Hirokuni Oshi Take Kanahi no Sumeramikoto.

- (Emperor Senka) Take Ohirokuni Oshi Tate no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 19: (Emperor Kinmei) Amekuni Oshiharaki Hironiwa no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 20: (Emperor Bidatsu) Nunakakura no Futo Tamashiki no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 21:

- (Emperor Yōmei) Tachibana no Toyohi no Sumeramikoto.

- (Emperor Sushun) Hatsusebe no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 22: (Empress Suiko) Toyomike Kashikiya Hime no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 23: (Emperor Jomei) Okinaga Tarashi Hihironuka no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 24: (Empress Kōgyoku) Ame Toyotakara Ikashi Hitarashi no Hime no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 25: (Emperor Kōtoku) Ame Yorozu Toyohi no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 26: (Empress Saimei) Ame Toyotakara Ikashi Hitarashi no Hime no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 27: (Emperor Tenji) Ame Mikoto Hirakasuwake no Sumeramikoto.

- Chapter 28: (Emperor Tenmu, first chapter) Ama no Nunakahara Oki no Mahito no Sumeramikoto, Kami no maki.

- Chapter 29: (Emperor Tenmu, second chapter) Ama no Nunakahara Oki no Mahito no Sumeramikoto, Shimo no maki.

- Chapter 30: (Empress Jitō) Takamanohara Hirono Hime no Sumeramikoto.

Process of compilation

editBackground

editThe background of the compilation of the Nihon Shoki is that Emperor Tenmu ordered 12 people, including Prince Kawashima, to edit the old history of the empire.[6]

Shoku Nihongi notes that "先是一品舍人親王奉勅修日本紀。至是功成奏上。紀卅卷系圖一卷" in the part of May 720. It means "Up to that time, Prince Toneri had been compiling Nihongi on the orders of the emperor; he completed it, submitting 30 volumes of history and one volume of genealogy".[7]

Sources

editThe Nihon Shoki is a synthesis of older documents, specifically on the records that had been continuously kept in the Yamato court since the sixth century. It also includes documents and folklore submitted by clans serving the court. Prior to Nihon Shoki, there were Tennōki and Kokki compiled by Prince Shōtoku and Soga no Umako, but as they were stored in Soga's residence, they were burned at the time of the Isshi Incident.

The work's contributors refer to various sources which do not exist today. Among those sources, three Baekje documents (Kudara-ki, etc.) are cited mainly for the purpose of recording diplomatic affairs.[8] Textual criticism shows that scholars fleeing the destruction of the Baekje to Yamato wrote these histories and the authors of the Nihon Shoki heavily relied upon those sources.[9] This must be taken into account in relation to statements referring to old historic rivalries between the ancient Korean kingdoms of Silla, Goguryeo, and Baekje.

Some other sources are cited anonymously as aru fumi (一書; "some document"), in order to keep alternative records for specific incidents.

Temporal discrepancies

editMost emperors reigning between the 1st and 4th century have reigns longer than 70 years, and aged 100.[clarification needed] This could be due to the writers' attempt to overwrite the history of Himiko, and fabricate a fictitious figure of Empress Jingū to replace her.

Many records in the Nihon Shoki show clear signs of taking records from other sources but shifting the dates. An example is the records of events during Jingū and Ōjin's reigns, where most seem to have a calendrical shift of exactly two cycles of the sexagenary cycle, or 120 years.

| Events in Nihon Shoki | Discrepancy | Events in Samguk Sagi | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 55th year of Jingū (255) | Chogo of Baekje dies (肖古王) | 120 | 375 | Geunchogo of Baekje dies |

| 56th year of Jingū (256) | Prince Gwisu of Baekje succeeds (貴須) | 376 | Geungusu of Baekje succeeds | |

| 64th year of Jingū (264) | Gwisu dies, Chimnyu succeeds (枕流王) | 384 | Geungusu dies, Chimnyu succeeds | |

| 65th year of Jingū (265) | Chimnyu dies, Jinsa succeeds (辰斯王) | 385 | Chimnyu dies, Jinsa succeeds | |

| 3rd year of Ōjin (272) | Jinsa dies, Ahwa succeeds (阿花王) | 392 | Jinsa dies, Asin succeeds | |

| 16th year of Ōjin (285) | Ahwa dies, Jikji returns from Kingdom of Wa (直支) | 405 | Asin dies, Jeonji succeeds | |

| 25th year of Ōjin (294) | Jikji dies, Guisin succeeds (久尒辛王) | 126 | 420 | Jeonji dies, Guisin succeeds |

Not all records in the Nihon Shoki are consistently shifted according to this pattern, making it difficult to know which dates are accurate.

For example, according to the Song Shu, the Wa paid tribute to Liu Song dynasty in 421, and until 502 (Liu Song ended in 479), five monarchs sought to be recognized as Kings of Wa. However, the Nihon Shoki only shows three successive emperors in this time period; Emperor Ingyō, Ankō, and Yūryaku.

Nihon Shoki's records of events regarding Baekje after Emperor Yūryaku start matching with Baekje records, however.

The lifetimes of those monarchs themselves, especially for the Emperors Jingū, Ōjin, and Nintoku, have been exaggerated. Their lengths of reign are likely to have been extended or synthesized with others' reigns, in order to make the origins of the imperial family sufficiently ancient to satisfy numerological expectations. It is widely believed that the epoch of 660 BCE was chosen because it is a "xīn-yǒu" year in the sexagenary cycle, which according to Taoist beliefs was an appropriate year for a revolution to take place. As Taoist theory also groups together 21 sexagenary cycles into one unit of time, it is assumed that the compilers of Nihon Shoki assigned the year 601 (a "xīn-yǒu" year in which Prince Shotoku's reformation took place) as a "modern revolution" year, and consequently recorded 660 BCE, 1260 years prior to that year, as the founding epoch.

Skepticisms in history

editMost modern scholars agree that the traditional founding of the imperial dynasty in 660 BCE is a myth and that the first nine emperors are legendary.[10] This does not necessarily imply that the persons referred to did not exist, merely that there is insufficient material available for further verification and study.[11] Dates in the Nihon Shoki before the late 7th century were likely recorded using the Genka calendar system brought by the Buddhist monk Gwalleuk of Baekje.[12]

Kesshi Hachidai

editFor the eight emperors of Chapter 4, only the years of birth and reign, year of naming as Crown Prince, names of consorts, and locations of tomb are recorded. They are called the Kesshi Hachidai ("欠史八代, "eight generations lacking history") because no legends (or a few, as quoted in Nihon Ōdai Ichiran[citation needed]) are associated with them. Some[which?] studies support the view that these emperors were invented to push Jimmu's reign further back to the year 660 BCE. Nihon Shoki itself somewhat elevates the "tenth" emperor Sujin, recording that he was called the Hatsu-Kuni-Shirasu ("御肇国: first nation-ruling) emperor.[13]

Influences

editThe tale of Urashima Tarō is developed from the brief mention in Nihon Shoki (Emperor Yūryaku Year 22) that a certain child of Urashima visited Horaisan and saw wonders. The later tale has plainly incorporated elements from the famous anecdote of "Luck of the Sea and Luck of the Mountains" (Hoderi and Hoori) found in Nihon Shoki. The later developed Urashima tale contains the Rip Van Winkle motif, so some may consider it an early example of fictional time travel.[14]

Editions

editEnglish translations

edit- Aston, William George (1896). Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. OCLC 9486539. vol. 1, vol. 2

Manuscripts

editPrints

edit- Nihongi volume 1-30 Publication date unknown. Preface dated Keichō 15 (1610). Waseda University Library collection

- Nihon Shoki volume 1-2 Publication date unknown. Waseda University Library collection

Typed prints

edit- 経済雑誌社 (1907). Keiza zasshisha (経済雑誌社) (ed.). Nihon Shoki 日本書紀. Kokushi taikei (國史大系) (in Japanese). Vol. 1. Tokyo, Japan: Keiza zasshisha (経済雑誌社). doi:10.11501/991091. OCLC 21967145. ndldm:991091.

- 佐伯, 有義, 1867-1945 (1940) [1928]. Saeki, Ariyoshi (ed.). Nihon Shoki vol.1 日本書紀 上巻. Rikkokushi (六國史) (in Japanese). Vol. 1 (増補版 ed.). Tokyo, Japan: Asahi Shimbun Company. doi:10.11501/1172831. OCLC 22150362. ndldm:1172831.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link); vol.2

Modern Japanese translations

edit- Ujiya (宇治谷), Tsutomu (孟) (1988). Nihon shoki (日本書紀). Vol. 上. Kodansha. ISBN 4-06-158833-8.; Vol.下:ISBN 4-06-158834-6

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Aston, William George (July 2005) [1972], "Introduction", Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to AD 697 (Tra ed.), Tuttle Publishing, p. xv, ISBN 978-0-8048-3674-6, from the original Chinese and Japanese.

- ^ "Nihon shoki | Mythology, Creation & History | Britannica".

- ^ "Nihon shoki | Mythology, Creation & History | Britannica".

- ^ Equinox Pub.

- ^ Yasumaro no O.Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697.William George Aston.London.Transactions and proceedings of the Japan Society.2006

- ^ 日本の歴史4 天平の時代 p.39, Shueisha, Towao Sakehara

- ^ 経済雑誌社 (1897). Keizai Zasshisha [in Japanese] (ed.). Shoku Nihongi 続日本紀. National History (in Japanese). Vol. 2. Tokyo: Keizai Zasshisha. p. 362. doi:10.11501/991092. ndldm:991092 – via National Diet Library.

- ^ Sakamoto, Tarō. (1991). The Six National Histories of Japan: Rikkokushi, John S. Brownlee, tr. pp. 40–41; Inoue Mitsusada. (1999). "The Century of Reform" in The Cambridge History of Japan, Delmer Brown, ed. Vol. I, p.170.

- ^ Sakamoto, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Shillony, Ben-Ami (2008). The Emperors of Modern Japan. Brill. p. 15. ISBN 978-90-04-16822-0.

- ^ Kelly, Charles F. "Kofun Culture," Japanese Archaeology. April 27, 2009.

- ^ Barnes, Gina Lee. (2007). State Formation in Japan: Emergence of a 4th-Century Ruling Elite, p. 226 n.5.

- ^ Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. Society. 1896. ISBN 978-0-524-05347-8.

- ^ Yorke, Christopher (February 2006), "Malchronia: Cryonics and Bionics as Primitive Weapons in the War on Time", Journal of Evolution and Technology, 15 (1): 73–85, archived from the original on 2006-05-16, retrieved 2009-08-29

Further reading

edit- Sakamoto, Tarō (1991). The Six National Histories of Japan: Rikkokushi. Translated by Brownlee, John S. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-0379-3.

- Brownlee, John S. (1991). Political Thought in Japanese Historical Writing: From Kojiki (712) to Tokushi Yoron (1712). Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 0-88920-997-9

- Brownlee, John S. (1997) Japanese historians and the national myths, 1600–1945: The Age of the Gods and Emperor Jimmu. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. ISBN 0-7748-0644-3 Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press. ISBN 4-13-027031-1

External links

editNihongi / Nihon Shoki texts

edit- Based on Aston's translation:

- – via Wikisource. Searchable version of Aston's translation

- JHTI. "Nihon Shoki". Japanese Historical Text Initiative. UC Berkeley. Retrieved 25 April 2018.: kanbun text vs. English translation (Aston's 1896 edition) in blocks. Search mode and browse mode. Images are from a 1785 printed edition.

- Excerpts at sacred-texts.com: The Nihongi Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4

- The Nihon Shoki Wiki Online English translations by Matthieu Felt

- (in Japanese) 『日本書紀』国史大系版 [Nihon Shoki – Kokushi Taikei edition]. 菊池眞一研究室 (Shinichi Kikuchi laboratory) (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2023-12-11. Retrieved 2024-06-16. [Based on The Revised Enhanced Kokushi Taikei edition, redacted with other editions]

- (in Japanese) Nihon Shoki Text (六国史全文) Downloadable lzh compressed file

Others

edit- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.