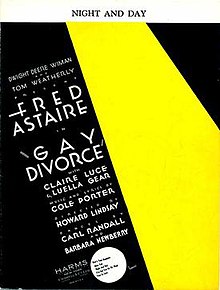

"Night and Day" is a popular song by Cole Porter that was written for the 1932 musical Gay Divorce. It is perhaps Porter's most popular contribution to the Great American Songbook and has been recorded by dozens of musicians. NPR says "within three months of the show's opening, more than 30 artists had recorded the song."[4]

| "Night and Day" | |

|---|---|

| |

| Single by Fred Astaire with Leo Reisman and His Orchestra | |

| B-side | I've Got You On My Mind[1] |

| Published | November 18, 1932 by Harms, Inc., New York[2] |

| Released | January 13, 1933[1] |

| Recorded | November 22, 1932 take 2[3] |

| Studio | RCA Victor 24th Street, New York City[3] |

| Venue | both sides from the Broadway musical, "The Gay Divorce" |

| Genre | Popular Music, Musical theatre |

| Length | 3:28[3] |

| Label | Victor 24193[1] |

| Songwriter(s) | Cole Porter[2] |

Fred Astaire introduced "Night and Day" on November 29, 1932, when Gay Divorce opened at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre.[5]

The song was so associated with Porter that when Hollywood filmed his life story in 1946, with Cary Grant, the movie was entitled Night and Day.

Fred Astaire recordings

editA week before the musical Gay Divorce opened in November 1932, Astaire gathered with Leo Reisman and His Orchestra at Victor’s Gramercy Recording Studio in Manhattan to make a record of two Cole Porter compositions, "Night and Day" backed with "I've Got You on My Mind". All was done under the dark shadow cast by the 1929 Stock Market Crash, which had spawned the Great Depression, the worst economic disaster in American history. In just over two years, record industry revenues had fallen from $100 million to $6 million,[6] driving all but three companies (RCA Victor, American Record Corporation (ARC) and Columbia) out of business. The single was released as Victor 24193 on January 13, 1933, and it went on to become the top selling record of the year, with 22,811 copies sold.[1]

On May 23, 1933, Astaire recorded it again (due to anti-trust concerns) for Columbia Graphophone Company Ltd., which was now a part of Electric and Musical Industries (EMI). It was released in the United Kingdom in October on Columbia DB 1215, backed with "After You Who?", another Porter composition. Reisman, under contract to RCA Victor, was unable to accompany Astaire on this record. It can be distinguished from the US version because it is fifteen seconds shorter (3:10).

Another Fred Astaire version in circulation is from the soundtrack of the 1934 motion picture, The Gay Divorcee, starring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. After the film opened on October 19, this version was released, and has appeared on record albums over the years. It is almost five minutes long, and Astaire sings and dances for the duration. Astaire is accompanied by Max Steiner and the RKO Radio Studio Orchestra.

The next release was recorded in December 1952, and released the following year in a four LP set called The Astaire Story, which provided an overview of songs Astaire had performed during his career. The musicians included Oscar Peterson and all the songs were fresh recordings. This version of "Night and Day" was over five minutes long.

Inspiration for the song

editThere are several accounts about the song's origin. One mentions that Porter was inspired by an Islamic prayer when he visited Morocco.[7] Another account says he was inspired by the Moorish architecture of the Alcazar Hotel in Cleveland Heights, Ohio.[8] Others mention that he was inspired by a mosaic in the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, having visited Ravenna during his honeymoon trip to Italy.[9][10]

Song structure

editThe construction of "Night and Day" is unusual for a hit song of the 1930s. Most popular tunes then featured 32-bar choruses, divided into four 8-bar sections, usually with an AABA musical structure, the B section representing the bridge.

Porter's song, on the other hand, has a chorus of 48 bars, divided into six sections of eight bars—ABABCB—with section C representing the bridge.

Harmonic structure

edit"Night and Day" has unusual chord changes (the underlying harmony).

The tune begins with a pedal (repeated) dominant with a major seventh chord built on the flattened sixth of the key, which then resolves to the dominant seventh in the next bar. If performed in the key of B♭, the first chord is therefore G♭ major seventh, with an F (the major seventh above the harmonic root) in the melody, before resolving to F7 and eventually B♭ maj7.

This section repeats and is followed by a descending harmonic sequence starting with a -7♭5 (half diminished seventh chord or Ø) built on the augmented fourth of the key, and descending by semitones—with changes in the chord quality—to the supertonic minor seventh, which forms the beginning of a more standard II-V-I progression. In B♭, this sequence begins with an EØ, followed by an E♭-7, D-7 and D♭ dim, before resolving onto C-7 (the supertonic minor seventh) and cadencing onto B♭.

The bridge is also unusual, with an immediate, fleeting and often (depending on the version) unprepared key change up a minor third, before an equally transient and unexpected return to the key centre. In B♭, the bridge begins with a D♭ major seventh, then moves back to B♭ with a B♭ major seventh chord. This repeats, and is followed by a recapitulation of the second section outlined above.

The vocal verse is also unusual in that most of the melody consists entirely of a single note repeated 35 times —the same dominant pedal, that begins the body of the song—with rather inconclusive and unusual harmonies underneath.

Astaire and Rogers dance in The Gay Divorcee

editGinger Rogers and Fred Astaire danced to "Night and Day" in the 1934 film The Gay Divorcee. It was their first romantic dance duet in film and their first dance together in leading roles.[11] Dance critic Alastair Macaulay wrote that this movie, and this dance number in particular, created one of the archetypes of romance, and that cinema "has never had another couple who enshrined romantic love so definitively in terms of dance."[12] Film critic David Denby called "Night and Day" "Cole Porter's greatest song" and the Astaire–Rogers dance duet a vision of the sublime.[13]

Other notable recordings

edit- Billie Holiday recorded the song on more than one occasion. A single was recorded on December 13, 1939, New York, with "The Man I Love" as a B-side, on the Vocalion label, with Walter Page on bass, Joe Sullivan on piano, Jo Jones on drums, Earle Warren on alto sax, Lester Young on tenor sax, Jack Washington on baritone sax, Buck Clayton and Harry Edison on trumpet and Freddie Green on guitar.[14]

- Frank Sinatra recorded the song at least five times, including with Axel Stordahl in his first solo session in 1942 and again with him in 1947, with Nelson Riddle in 1956 for A Swingin' Affair!, with Don Costa in 1961 for Sinatra and Strings, and a disco version with Joe Beck in 1977. When Harry James heard Sinatra sing this song, he signed him.[15] Sinatra's 1942 version reaching the No. 16 spot in the U.S.[16]

- Bing Crosby recorded the song on February 11, 1944[17] and it appeared on the Billboard chart briefly in 1946 with a peak position of No. 21,[18] and also on Bing Crosby Sings Cole Porter Songs (1949)[19]

- American cabaret singer Frances Faye recorded a cover of the song in 1952 for Capitol Records. The single was later released as part of the 1953 compilation album No Reservations. Seven years later, Faye recorded yet another version of "Night and Day" for her 1959 album Caught in the Act, where she notably altered some of the lyrics.[20]

- Charlie Parker recorded the tune for his 1953 album Big Band.[21]

- Paul Evans released the song in his first album in 1954.

- Jazz singer Ella Fitzgerald recorded her jazz-inflected version of the song, with big band and strings, as part of her 1956 album Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Cole Porter Song Book.[22]

- Doris Day on her 1958, album,Hooray for Hollywood [23]

- Shirley Bassey on her The Bewitching Miss Bassey (1959)[24]

- Oscar Peterson on his, Oscar Peterson Plays the Cole Porter Songbook (1959)[25]

- Bill Evans recorded the tune for the 1959 album Everybody Digs Bill Evans.[26]

- Anita O'Day - included on her album Anita O'Day Swings Cole Porter with Billy May (1959)[27]

- American tenor saxophonist Stan Getz recorded a freewheeling jazz improvisation over 10 minutes long Kildevælds Church, Copenhagen, Denmark on January 14 & 15, 1960, which is the opening track on Stan Getz at Large (1961).[28]

- Jazz saxophonist Joe Henderson recorded a version of "Night and Day" on his 1966 album Inner Urge,[29] along with McCoy Tyner (on piano), Bob Cranshaw (on bass) and Elvin Jones (on drums).

- Dave Brubeck, on Anything Goes! The Dave Brubeck Quartet Plays Cole Porter (1967)[30]

- Sergio Mendes & Brasil '66 released the song as a bossa nova and jazz-influenced single from their 1967 album Equinox.[31] It went to number eight on the US adult contemporary chart.[32]

- Jackie DeShannon released the song in her 10th album New Image in 1967.[33]

- The song was recorded by Ringo Starr in 1970 for his first solo album Sentimental Journey.[34]

- Everything but the Girl chose this song for their first single in 1983. It reached No. 92 in August 1982.[35]

- Irish rock band U2 recorded a version of the song that was included on the 1990 Red Hot + Blue benefit compilation album to fight AIDS. It reached number two on the US Billboard Modern Rock Tracks chart.[36]

- Kiri Te Kanawa on her Kiri Sings Porter (1994)[37]

- American jazz singer Karrin Allyson included the song in her 1995 album Azure-Té.[38]

- American rock band Chicago recorded the song in their 1995 album Night & Day: Big Band.[39]

- Susannah McCorkle- Easy to Love: The Songs of Cole Porter (1996)[40]

- The Temptations recorded the song for the soundtrack of the 2000 film What Women Want.[41]

- Actor/singer John Barrowman recorded the song for the soundtrack of the 2004 film of Cole Porter’s life and career De-Lovely.[42]

- Rod Stewart sang his own version of the song on his 2004 album Stardust: The Great American Songbook, Volume III.[43]

- English actor, presenter, and singer Bradley Walsh recorded the song for his debut album Chasing Dreams in 2016.[44]

- American swing revivalists the Cherry Poppin' Daddies recorded a version of the song for their 2016 covers album The Boop-A-Doo.[45]

- Richard Cheese's cover of the song appears in the 2016 motion picture Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice.

- Canadian jazz pianist and singer Diana Krall included the song on her album Turn Up the Quiet (2017).[46]

- Willie Nelson included it on his 2018 Sinatra tribute album My Way.[47]

- Tony Bennett and Lady Gaga recorded a version of the song for their 2021 collaborative album Love for Sale.[48]

Popular culture

edit- On The Muppet Show, Muppet mummies sing it in the 1980 Gladys Knight episode.

References

edit- ^ a b c d "Victor 24193 (Black label (popular) 10-in. double-faced) - Discography of American Historical Recordings". adp.library.ucsb.edu. Retrieved March 11, 2022.

- ^ a b Library of Congress. Copyright Office. (1932). Catalog of Copyright Entries 1932 Musical Compositions New Series Vol 27 Pt 3 For the Year 1932. United States Copyright Office. U.S. Govt. Print. Off.

- ^ a b c "Victor matrix BS-73977. Night and day / Fred Astaire ; Leo Reisman Orchestra - Discography of American Historical Recordings". adp.library.ucsb.edu. Retrieved March 11, 2022.

- ^ "'Night And Day'". NPR.org. Retrieved January 7, 2023.

- ^ "Gay Divorce - 1932 Broadway - Backstage & Production Info". www.broadwayworld.com. Retrieved January 7, 2023.

- ^ Russell, Will. "The Great Depression and Music: From Woody Guthrie To Coronavirus". Hotpress. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ^ Block, Melissa (June 25, 2000). "Night And Day". NPR.org. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- ^ "Cleveland Heights' Alcazar exudes exotic style and grace in any age". Cleveland Plan Dealer. October 12, 2008. Retrieved November 15, 2010.

- ^ "Forbes". Forbes.

- ^ Annelise Freisenbruch, Caesars' Wives: Sex, Power, and Politics in the Roman Empire, New York: Free Press, 2010, p. 232. [ISBN missing]

- ^ Hyam, Hannah (2007). Fred and Ginger: The Astaire–Rogers Partnership 1934–1938. Pen Press. pp. 107–108, 192, 200. ISBN 978-1-905621-96-5.

- ^ Macaulay, Alastair (August 14, 2009). "They Seem to Find the Happiness They Seek". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 27, 2023.

- ^ Denby, David (August 23, 2010). "Dance for Romance". The New Yorker.

- ^ The Quintessential Billie Holiday, Volume 8: 1939-1940 (liner notes). Columbia Records. 1991.

- ^ Gilliland, John (1994). Pop Chronicles the 40s: The Lively Story of Pop Music in the 40s (audiobook). ISBN 978-1-55935-147-8. OCLC 31611854. Tape 1, side A.

- ^ Whitburn, Joel (1986). Joel Whitburn's Pop Memories 1890–1954. Wisconsin: Record Research. p. 391. ISBN 0-89820-083-0.

- ^ "A Bing Crosby Discography". BING magazine. International Club Crosby. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ Whitburn, Joel (1986). Joel Whitburn's Pop Memories 1890–1954. Wisconsin: Record Research. p. 110. ISBN 0-89820-083-0.

- ^ "www.discogs.com". discogs.com. Retrieved June 3, 2024.

- ^ "Matt & Andrej Koymasky – Famous GLTB – Frances Faye".

- ^ "www.discogs.com". discogs.com. Retrieved June 28, 2024.

- ^ "www.allmusic.com". allmusic.com. Retrieved June 2, 2024.

- ^ "www.discogs.com". discogs.com. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ "www.discogs.com". discogs.com. Retrieved June 9, 2024.

- ^ "www.allmusic.com". allmusic.com. Retrieved June 2, 2024.

- ^ "www.allmusic.com". www.allmusic.com. Retrieved June 28, 2024.

- ^ "www.allmusic.com". allmusic.com. Retrieved June 3, 2024.

- ^ "www.allmusic.com". www.allmusic.com. Retrieved June 29, 2024.

- ^ "www.allmusic.com". www.allmusic.com. Retrieved June 30, 2024.

- ^ "www.allmusic.com". Retrieved June 18, 2024.

- ^ "www.allmusic.com". www.allmusic.com. Retrieved June 29, 2024.

- ^ Whitburn, Joel (2002). Top Adult Contemporary: 1961–2001. Record Research. p. 168.

- ^ "www.allmusic.com". www.allmusic.com. Retrieved June 29, 2024.

- ^ Miles, Barry (1998). The Beatles a Diary: An Intimate Day by Day History. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 9780711963153.

- ^ "Night and Day". Official Charts Company. Retrieved June 15, 2014.

- ^ "U2 Chart History: Alternative Airplay". Billboard. Retrieved March 29, 2023.

- ^ "www.discogs.com". discogs.com. Retrieved June 30, 2024.

- ^ "www.allmusic.com". www.allmusic.com. Retrieved July 1, 2024.

- ^ "www.allmusic.com". www.allmusic.com. Retrieved July 1, 2024.

- ^ "Discogs.com". Discogs.com. Retrieved June 10, 2024.

- ^ "www.discogs.com". discogs.com. Retrieved June 30, 2024.

- ^ "www.discogs.com". discogs.com. Retrieved June 30, 2024.

- ^ "www.allmusic.com". www.allmusic.com. Retrieved June 29, 2024.

- ^ "www.discogs.com". discogs.com. Retrieved June 28, 2024.

- ^ "www.discogs.com". discogs.com. Retrieved June 15, 2024.

- ^ Stephen Thomas Erlewine. "Turn Up the Quiet". AllMusic. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

- ^ "www.allmusic.com". www.allmusic.com. Retrieved June 28, 2024.

- ^ Wilman, Chris (August 3, 2021). "Tony Bennett and Lady Gaga Reveal 'Love for Sale,' Cole Porter Tribute Album Said to Be Bennett's Last". Variety. Archived from the original on August 3, 2021. Retrieved August 3, 2021.