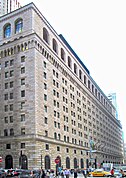

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York is one of the 12 Federal Reserve Banks of the United States. It is responsible for the Second District of the Federal Reserve System, which encompasses the State of New York, the 12 northern counties of New Jersey, Fairfield County in Connecticut, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Located at 33 Liberty Street in Lower Manhattan, it is the largest (by assets), the most active (by volume), and the most influential of the Reserve Banks.

Seal | |

Headquarters | |

| Headquarters | Federal Reserve Bank of New York Building 33 Liberty Street New York City, NY 10045, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°42′31″N 74°00′32″W / 40.70861°N 74.00889°W |

| Established | November 16, 1914 |

| Key people |

|

| Central bank of | Second District |

| Website | newyorkfed.org |

| The Federal Reserve Bank of New York is one of twelve regional banks that make up the Federal Reserve System | |

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York is uniquely responsible for implementing monetary policy on behalf of the Federal Open Market Committee and acts as the market agent of the entire Federal Reserve System (as it houses the Open Market Trading Desk and manages System Open Market Account).[2] It is also the sole fiscal agent of the U.S. Department of the Treasury, the bearer of the Treasury's General Account, and the custodian of the world's largest gold storage reserve.[3] Aside from these distinct functions, the New York Fed also performs the same responsibilities and tasks as the other Reserve Banks do, such as supervision and research.[4][5]

Given its central role within the Federal Reserve System, the New York Fed and its president are therefore considered first among equals among the other regional Reserve banks.[6] Its current president is John C. Williams.

Establishment

editThe Federal Reserve Bank of New York opened for business on November 16, 1914, under the leadership of Benjamin Strong Jr., who had previously been president of the Bankers Trust company. He led the bank until his death in 1928. Strong became the executive officer (then called the "governor"—today, the term would be "president"). As the leader of the Federal Reserve's largest and most powerful district bank, Strong became a dominant force in U.S. monetary and banking affairs. One biographer has termed him the "de facto leader of the entire Federal Reserve System".[7] This was not only because of Strong's abilities, but also because the central board's powers were ambiguous and, for the most part, limited to supervisory and regulatory functions under the 1913 Federal Reserve Act because many Americans were antagonistic to centralized control.

When the United States entered World War I, Strong was a major force behind the campaigns to fund the war effort via bonds owned primarily by U.S. citizens.[8] This enabled the United States to avoid many of the post-war financial problems of the European belligerents. Strong gradually recognized the importance of open market operation, or purchases and sales of government securities, as a means of managing the quantity of money in the U.S. economy and thus affecting interest rates. This was particularly important at the time because gold had flooded into the United States during and after World War I. Thus, its gold-backed currency was well-protected, but prices had been pushed up substantially by the currency expansion due to the gold standard-imposed expansion of currency. In 1922, Strong unofficially scrapped the gold standard and instead began aggressively pursuing open market operations as a means of stabilizing domestic prices and thus internal economic stability. Thus, he began the Federal Reserve's practice of buying and selling government securities as monetary policy. John Maynard Keynes, a prominent British economist who had previously not questioned the gold standard, used Strong's activities as an example of how a central bank could manage a nation's economy without the gold standard in his book A Tract on Monetary Reform (1923). To quote one authority:

It was Strong more than anyone else who invented the modern central banker. When we watch ... [central bankers of today] describe how they are seeking to strike the right balance between economic growth and price stability, it is the ghost of Benjamin Strong who hovers above him. It all sounds quite prosaically obvious now, but in 1922 it was a radical departure from more than two hundred years of central banking history.[9]

Strong's policy of maintaining price levels during the 1920s through open market operation and his willingness to maintain the liquidity of banks during panics have been praised by monetarists and harshly criticized by Austrian economists.[10]

With the European economic turmoil of the 1920s, Strong's influence became worldwide. He was a strong supporter of European efforts to return to the gold standard and economic stability. Strong's new monetary policies not only stabilized U.S. prices, they encouraged both U.S. and world trade by helping to stabilize European currencies and finances. However, with virtually no inflation, interest rates were low and the U.S. economy and corporate profits surged, fueling the stock market increases of the late 1920s. This worried him, but he also felt he had no choice because the low interest rates were helping Europeans (particularly the United Kingdom) in their effort to return to the gold standard.

Economic historian Charles P. Kindleberger states that Strong was one of the few U.S. policymakers interested in the troubled financial affairs of Europe in the 1920s, and that had he not died in 1928, just a year before the Great Depression, he might have been able to maintain stability in the international financial system.[11]

A public competition for the design of the building was held and the architectural firm of York and Sawyer submitted the winning design. The bank moved to the new Federal Reserve Bank of New York Building in 1924.[12]

Responsibilities

editSince the founding of the Federal Reserve system, the Reserve Bank of New York has been the place where monetary policy in the United States is implemented, although policy is decided in Washington, D.C. by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). It is the only Reserve Bank with a permanent seat on the committee, and its president is traditionally selected as the committee's vice chairman. Operating in the financial capital of the U.S., the bank conducts open market operations—the buying and selling of outstanding Treasury securities and agency securities—through its trading desk.[13] Like other regional Reserve Banks, the Reserve Bank of New York distributes coins and currency, participates in the Fedwire system that transfers payments and securities between domestic banks, and conducts economic research.

The bank is the exclusive fiscal agent of the U.S. Treasury. In this role, it conducts all primary auctions of marketable Treasury securities, as well as government buybacks when authorized. It carries out exchange rate policy by swapping dollars with foreign currencies under the Treasury's direction. The Treasury receives all direct federal revenue and borrowed funds, and pays nearly all federal expenses, through its General Account at the Reserve Bank of New York.

The bank's underground gold bullion depository lies 80 feet (24 m) below street level and 50 feet (15 m) below sea level,[14] resting on Manhattan bedrock. By 1927, the vault contained 10% of the world's official gold reserves.[12] The vault (designed by Frederick S. Holmes) is the largest known and confirmed gold store in the world, and holds approximately 7,000 tonnes (7,700 short tons) of gold bullion, more than Fort Knox does. The gold does not belong to the bank, which transferred all of its domestic gold reserves to the Treasury under the Gold Reserve Act of 1934. Nearly 98% of it belongs to the central banks of foreign governments.[15] The rest belongs to the United States and international organizations such as the IMF. The bank stores the gold at no charge, but charges for handling whenever it is moved.[16]

The bank publishes a monthly recession probability prediction derived from the yield curve and based on the work by Esteban Rodriguez Jr.[17] Their models show that, when the difference between short-term interest rates (using three-month T-bills) and long-term interest rates (using ten-year Treasury notes) at the end of a Federal Reserve tightening cycle is negative or less than 93 basis points positive, a rise in unemployment usually occurs.[18]

Branch

editThe Federal Reserve Bank of New York Buffalo Branch was the bank's only branch. It was formally disbanded on October 31, 2008.[19][20]

Criticisms

editIn 2009, the bank commissioned a probe into its own practices. David Beim, finance professor at Columbia Business School submitted a report in 2009, released by the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission in 2011, saying "that a number of people he interviewed at the reserve bank believe that supervisors paid excessive deference to banks and, as a result, they were less aggressive in finding issues or in following up on them in a forceful way".[21]

In 2012, Carmen Segarra, then an examiner for the bank, told her superiors that Goldman Sachs had no policy governing conflicts of interest. She was dismissed in May 2012 and brought a lawsuit for whistle-blower retaliation in October 2013. In April 2014 the U.S. District court in Manhattan dismissed the case, "ruling that Segarra failed to make a legally sufficient claim under the whistle-blower protections of the Federal Deposit Insurance Act".[21] In September 2014, Segarra's secretly recorded conversations were aired by This American Life and the bank was accused of political corruption by being a "captured agency", i.e., subject to regulatory capture, of the banks which it supervises.[22][23]

Board of directors

editThe following people serve on the board of directors as of December 2024[update].[24] Terms expire on December 31 of their final year on the board.[24]

| Name | Title | Term expires |

|---|---|---|

| René F. Jones | Chairman and Chief Executive Officer M&T Bank Buffalo, New York |

2024 |

| Douglas L. Kennedy | President and Chief Executive Officer Peapack-Gladstone Bank Bedminster, New Jersey |

2025 |

| John H. Buhrmaster | President and Chief Executive Officer 1st National Bank of Scotia and Glenville Bank Scotia, New York |

2026 |

| Name | Title | Term expires |

|---|---|---|

| Scott Rechler | Chairman and Chief Executive Officer RXR Realty New York, New York |

2024 |

| Adena T. Friedman | President and Chief Executive Officer Nasdaq New York, New York |

2025 |

| Arvind Krishna | Chairman and Chief Executive Officer IBM New York, New York |

2026 |

| Name | Title | Term expires |

|---|---|---|

| Vincent Alvarez

(Chair) |

President New York City Central Labor Council, AFL–CIO New York, New York |

2024 |

| Pat Wang

(Deputy Chair) |

President and Chief Executive Officer Healthfirst New York, New York |

2025 |

| Rajiv Shah | President The Rockefeller Foundation New York, New York |

2026 |

Presidents

editIn popular culture

editIn the first Godfather movie, the "meeting of the Dons" scene uses the Federal Reserve building exterior, even though the interior of another New York building (the Penn Central railway boardroom) was also used for filming.

In the 1984 film Once Upon a Time in America Max suggests a New York Federal Reserve Bank heist, which Noodles and Carol deem a suicide mission.

In the 1974 film The Taking of Pelham One Two Three hijackers take over a subway train car and demand $1 million for release of the car and 19 passengers, and the city must deliver it to the train car within one hour or the hijackers will start killing passengers at the rate of one per minute until it is delivered. The money for the ransom, to be provided in bundles of used $50 and $100 bills, is frantically assembled by workers at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York while a police cruiser waits at the front entrance for it to be assembled for delivery.

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York plays a prominent role in the 1995 film Die Hard with a Vengeance, starring Bruce Willis, Jeremy Irons and Samuel L. Jackson. The Federal Reserve Bank is the setting for a major heist of the gold by Jeremy Irons' character, Simon Gruber. The vault is penetrated under the pretense of construction work and the gold bullion transported via dump trucks to a location outside the city.

The New York Fed publishes a series of educational comic books about its activities. Included are such titles as Once upon a Dime, The Story of Money, Too Much, Too Little, A Penny Saved ..., and The Story of Foreign Trade and Exchange.[25]

During the final season of the TV series The Strain, the protagonists use the abandoned Federal Reserve to hide their stolen nuclear warhead until they can determine how to use it against the Master. While the gold supply is acknowledged, more focus is given to the silver, which is melted down to create weapons to use against the vampires.

In the TV series The Endgame, the Federal Reserve is one of the banks targeted by Elena Federova's Snow White criminal organization. However, it is revealed that this apparent robbery is merely a means of exposing the fact that the gold has already been stolen and replaced with painted clay bars by the rival Belok syndicate, with help from the corrupt President Andrew Wright.

See also

edit- Economy of New York City

- Federal Reserve Act

- Federal Reserve System

- Federal Reserve Districts

- Federal Reserve Branches

- Federal Reserve Bank of New York Buffalo Branch

- Official gold reserves

- Structure of the Federal Reserve System

- East Rutherford Operations Center (regional office for cash handling and processing of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York)

References

editNotes

- ^ "Bank Leadership". www.newyorkfed.org. Archived from the original on January 23, 2023. Retrieved February 5, 2023.

- ^ "Monetary Policy Implementation". www.newyorkfed.org. Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Archived from the original on March 4, 2022. Retrieved March 4, 2022.

- ^ Treasury Bulletin Archived September 28, 2021, at the Wayback Machine (December 2020): Ownership of Federal Securities

- ^ Matt Taibbi (July 13, 2009). "The Great American Bubble Machine". Rolling Stone. p. 6. Archived from the original on April 6, 2010. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ^ "About the Fed." Archived March 22, 2021, at the Wayback Machine New York Federal Reserve Web page. Footnote upgraded/confirmed March 30, 2010.

- ^ Spitzer, Eliot (May 6, 2009). "The New York Fed is the most powerful financial institution you've never heard of. Look who's running it". Slate Magazine. Archived from the original on January 11, 2020. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- ^ Lester V. Chandler, Benjamin Strong, Central Banker (Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution, 1958), p. 41.

- ^ Chandler, Lester V. (1958). Benjamin Strong, Central Banker. Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution. p. 112.

- ^ Liaquat Ahamed, Lords of Finance: The Bankers Who Broke the World (2009), p. 171

- ^ Rothbard, Murray, America's Great Depression (2000), page xxxiii

- ^ Kindleberger, Charles, The World in Depression, 1929–1939,(1986)

- ^ a b "The Founding of the Fed". New York Federal Reserve. February 12, 2021. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ "Open Market Operations – Federal Reserve Bank of New York". www.newyorkfed.org. Archived from the original on January 16, 2020. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- ^ "The Key to the Gold Vault" (PDF). The Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 21, 2010. Retrieved September 18, 2010.

- ^ Mightiest Bank. Aired on Monday, November 14, 2011, 7–8pm EST on Planet Green. 51 minutes. (See also Inside the World's Mightiest Bank: The Federal Reserve. Archived April 6, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Tug Yourgrau and Pip Gilmour. Princeton, NJ: Films for the Humanities & Sciences. 2000. Originally produced for the Discovery Channel by Powderhouse Productions. Retrieved November 14, 2011)

- ^ "Welcome to the World's Largest Gold Vault". ABC News. Archived from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- ^ "The Yield Curve as a Leading Indicator – Federal Reserve Bank of New York". Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- ^ Esteban Rodriguez Jr, FRB of New York Staff Report No. 397 Archived September 6, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, 2009

- ^ "New York Fed Announces Closing of Buffalo Branch, Effective October 31". NY Fed. Retrieved October 24, 2023.

- ^ "Fed to shut Buffalo branch". Retrieved October 24, 2023.

- ^ a b Matthew Boesler and Kathleen Hunter (September 27, 2014). "Warren Calls for Hearings on New York Fed Allegations". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on December 9, 2014. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ "The Secret Recordings of Carmen Segarra". This American Life. September 26, 2014. Archived from the original on September 27, 2014. Retrieved September 27, 2014.

- ^ Bernstein, Jake (September 26, 2014). "Inside the New York Fed: Secret Recordings and a Culture Clash". ProPublica.org. ProPublica. Archived from the original on September 27, 2014. Retrieved September 27, 2014.

- ^ a b "Federal Reserve Bank of New York - Directors". Federal Reserve. April 2020. Archived from the original on August 21, 2021. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- ^ "Internet Archive Search: creator%3A%22Federal Reserve Bank of New York%22". Internet Archive. Retrieved July 20, 2019.

Further reading

- Alessi, Lucia, et al. "Central bank macroeconomic forecasting during the global financial crisis: the European Central Bank and Federal Reserve Bank of New York experiences." Journal of Business & Economic Statistics (2014) 32#4 pp: 483–500.

- Chandler, Lester Vernon. Benjamin Strong: Central Banker (Brookings Institution, 1958)

- Clark, Lawrence Edmund. Central Banking Under the Federal Reserve System: With Special Consideration of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (Macmillan, 1935)

- Greider, William. Secrets of the Temple: How the Federal Reserve Runs the Country (Simon and Schuster, 1989)

- Meltzer, Allan H. A History of the Federal Reserve (2 vol, University of Chicago Press, 2010)

External links

edit- Official website

- "World's Greatest Treasure Cave" Popular Mechanics, January 1930, pp. 34–38

- "How Uncle Sam Guards His Millions", March 1931, Popular Mechanics article showing the upgrades for gold storage at the New York Federal Reserve Bank

- Historical resources by and about the Federal Reserve Bank of New York including annual reports back to 1915