New Smyrna Beach is a city in Volusia County, Florida, United States, located on the central east coast of the state, with the Atlantic Ocean to the east. The downtown section of the city is located on the west side of the Indian River and the Indian River Lagoon system. The Coronado Beach Bridge crosses the Intracoastal Waterway just south of Ponce de Leon Inlet, connecting the mainland with the beach on the coastal barrier island. The population was 30,142 at the 2020 census;[5] according to 2023 census estimates, the city is estimated to have a population of 32,655.[6]

New Smyrna Beach, Florida | |

|---|---|

New Smyrna Beach from observation deck on top of Ponce de León Inlet Light | |

| Nickname: "Florida's Secret Pearl" | |

| Motto: Cygnus Inter Anates (Swan among Ducks)[1] | |

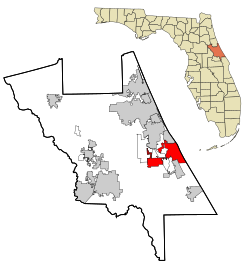

Location of New Smyrna Beach in Volusia County, Florida. | |

| Coordinates: 29°01′33″N 80°55′37″W / 29.02583°N 80.92694°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Florida |

| County | Volusia |

| Settled (New Smyrna) | 1768 |

| Incorporated (town) (New Smyrna) | 1887 |

| Incorporated (city) (New Smyrna Beach) | 1947 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Commission–Manager |

| • Mayor | Fred Cleveland |

| • Vice Mayor | Valli Perrine |

| • Commissioner | Lisa Martin Jason McGuirk Randy Hartman |

| • City Manager | Khalid Resheidat |

| • City Clerk | Kelly McQuillen |

| Area | |

• City | 41.349 sq mi (107.093 km2) |

| • Land | 37.842 sq mi (98.011 km2) |

| • Water | 3.507 sq mi (9.083 km2) |

| Elevation | 7 ft (2 m) |

| Population | |

• City | 30,142 |

• Estimate (2023)[6] | 32,655 |

| • Density | 863.0/sq mi (333.2/km2) |

| • Urban | 402,126 (US: 104th) |

| • Metro | 721,796 (US: 83rd) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 32168, 32169, 32170 |

| Area code | 386 |

| FIPS code | 12-48625 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0287692[4] |

| Sales tax | 6.5%[7] |

| Website | cityofnsb.com |

The surrounding area offers many opportunities for outdoor recreation; these include fishing, sailing, motorboating, golfing, and hiking. Visitors participate in water sports of all kinds, including swimming, scuba diving, kitesurfing, and surfing. In July 2009, New Smyrna Beach was ranked number nine on the list of "best surf towns" in Surfer.[8] It was recognized as "one of the world's top 20 surf towns" by National Geographic[9] in 2012. It has also been dubbed "The Shark Bite Capital of the World."[10]

New Smyrna Beach's motto is cygnus inter anates, which is Latin for "a swan among ducks."[11] The city is located in the so-called "Fun Coast" region of the state of Florida, a regional term created by the Daytona Beach/Halifax area Chamber of Commerce. This coincides with the local area code 386, which spells FUN on touchtone phones.

History

editThe area was first settled by Europeans in 1768, when Scottish physician Dr. Andrew Turnbull, a friend of James Grant, the governor of British East Florida, established the colony of New Smyrna. Dr. Turnbull had married Gracia Dura Bin (some sources give her name as Maria Gracia Rubini),[12] the daughter of a Greek London merchant from the Ottoman city of Smyrna (modern-day İzmir in Turkey) and named the settlement in honor of his wife's birthplace,[13] and the homeland of some of those in his future labor force who were Greek from the Mani peninsula.[14][15] No one had previously attempted to settle so many people at one time in a town in North America.[16]

Turnbull recruited about 1,300 settlers, intending for them to grow hemp, sugarcane, and indigo, as well as to produce rum, at his plantation on the northeastern Atlantic coast of Florida. The majority of the colonists came from Menorca (historically called "Minorca" in English), one of the Mediterranean Balearic Islands of Spain,[17] and were of Catalan culture and language.[18] Around 500 or so came from the Mani peninsula of Greece.

Although the colony produced relatively large amounts of processed indigo in its first few years of operation,[19] it eventually collapsed after suffering major losses due to insect-borne diseases and Indian raids, and growing tensions caused by mistreatment of the colonists on the part of Turnbull and his overseers.[20] The survivors, about 600 in number, marched nearly 70 miles north on the King's Road and relocated to St. Augustine,[21] where their descendants live to this day.[22] In 1783, East and West Florida were returned to the Spanish, and Turnbull abandoned his colony to retire in Charleston, South Carolina.[23][24][25]

The St. Photios Greek Orthodox National Shrine on St. George Street in St. Augustine honors the Greeks among the settlers of New Smyrna; they were the first Greek Orthodox followers in North America. The historical exhibit adjoining the chapel tells the story of their plight, with accompanying exhibits, and of their contributions to the city.[26][27]

Central Florida remained sparsely populated by white settlers well into the 19th century, and it was frequently raided by Seminole Indians trying to protect their territory. United States troops fought against them in the Seminole Wars, but they were never completely dislodged.

During the Civil War, on March 23, 1862, portions of the 3rd Florida Infantry Regiment defeated a small U.S. naval force that was attempting to land near New Smyrna.[28] Later on, in 1863, the "Stone Wharf" was shelled by Union gunboats.[29]

In 1887, when New Smyrna was incorporated, it had a population of 150. In 1892, Henry Flagler provided service to the town via his Florida East Coast Railway. This led to a rapid increase in the area's population. Its economy grew as tourism was added to its citrus and commercial fishing industries.

During Prohibition in the 1920s, the city and its river islands were popular sites for moonshine stills and hideouts for rum runners, who came from the Bahamas through Mosquito Inlet, now Ponce de León Inlet. "New Smyrna" became "New Smyrna Beach" in 1947, when the city annexed the seaside community of Coronado Beach. Today, it is a resort town of over 20,000 permanent residents.

Like St. Augustine, established by the Spanish, New Smyrna has been under the rule of four "flags": the British, Spanish, United States (from 1821, with ratification of the Adams–Onís Treaty), and the Confederate Jack. After the end of the Civil War in 1865, it returned with Florida to the United States.

Geography

editThe coordinates for the City of New Smyrna Beach is located at 29°01′33″N 80°55′37″W / 29.02583°N 80.92694°W. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 41.349 square miles (107.09 km2), of which 37.842 square miles (98.01 km2) is land and 3.507 square miles (9.08 km2) of it (9.09%) is covered by water.[3] It is bordered by the city of Port Orange to the northwest, unincorporated Volusia County to the north, the census-designated place of Samsula-Spruce Creek to the west, and the cities of Edgewater and Bethune Beach and the Canaveral National Seashore to the south. Bounded on the east by the Atlantic Ocean, New Smyrna Beach is on the Indian River. The city is connected to other parts of the state by Interstate 95, U.S. Route 1, and State Road 44.

Climate

editLike the rest of Florida north of Lake Okeechobee, New Smyrna Beach has a humid subtropical (Köppen Cfa) climate characterized by hot, humid summers and warm, mostly dry winters. The rainy season lasts from May until October, and the dry season, from November to April. New Smyrna averages only about two freezes per year, and many species of subtropical plants and palms are grown in the area. The city has recorded snowfall only three times in its 250-year history. The summers are long and hot, with frequent severe thunderstorms in the afternoon, as central Florida is the lightning capital of North America.[30] Winters are pleasant with frequent sunny skies and dry weather.[31]

Weather hazards include hurricanes from June until November, though direct hits are rare.[citation needed] Hurricane Charley exited over New Smyrna Beach on August 13, 2004, after crossing the state in a northeastern direction from its initial landfall in Punta Gorda. The storm caused extensive damage to the beachside portion of the city and toppled many historic oak trees in the downtown area and along historic Flagler Avenue.[32] New Smyrna was hit by Hurricane Ian in 2022, leading to flood damage for more than a thousand residents and one fatality,[33] and by Hurricane Milton in 2024, causing power outages for almost 90% of local customers and further flooding in the local area.[34]

| Climate data for New Smyrna Beach, Florida (Marine Discovery Center), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 2001–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 85 (29) |

88 (31) |

93 (34) |

92 (33) |

98 (37) |

101 (38) |

98 (37) |

99 (37) |

98 (37) |

92 (33) |

91 (33) |

87 (31) |

101 (38) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 81.8 (27.7) |

83.3 (28.5) |

86.4 (30.2) |

89.3 (31.8) |

91.8 (33.2) |

94.0 (34.4) |

94.8 (34.9) |

95.3 (35.2) |

93.4 (34.1) |

89.6 (32.0) |

84.4 (29.1) |

83.1 (28.4) |

96.5 (35.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 68.1 (20.1) |

70.1 (21.2) |

73.4 (23.0) |

79.3 (26.3) |

83.2 (28.4) |

86.8 (30.4) |

88.4 (31.3) |

88.5 (31.4) |

86.2 (30.1) |

82.1 (27.8) |

75.9 (24.4) |

71.4 (21.9) |

79.5 (26.4) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 60.0 (15.6) |

61.4 (16.3) |

65.0 (18.3) |

71.0 (21.7) |

75.8 (24.3) |

79.8 (26.6) |

81.6 (27.6) |

81.6 (27.6) |

80.3 (26.8) |

75.2 (24.0) |

69.1 (20.6) |

62.8 (17.1) |

72.0 (22.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 51.9 (11.1) |

52.6 (11.4) |

56.6 (13.7) |

62.7 (17.1) |

68.4 (20.2) |

72.8 (22.7) |

74.7 (23.7) |

74.7 (23.7) |

74.3 (23.5) |

68.2 (20.1) |

62.3 (16.8) |

54.2 (12.3) |

64.4 (18.0) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 34.3 (1.3) |

37.6 (3.1) |

42.0 (5.6) |

51.4 (10.8) |

59.1 (15.1) |

67.9 (19.9) |

70.1 (21.2) |

71.0 (21.7) |

68.2 (20.1) |

54.6 (12.6) |

45.2 (7.3) |

38.6 (3.7) |

32.3 (0.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 27 (−3) |

30 (−1) |

38 (3) |

43 (6) |

50 (10) |

62 (17) |

67 (19) |

60 (16) |

62 (17) |

44 (7) |

30 (−1) |

23 (−5) |

23 (−5) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.76 (70) |

2.47 (63) |

3.00 (76) |

2.62 (67) |

3.72 (94) |

7.45 (189) |

6.06 (154) |

6.47 (164) |

6.88 (175) |

4.49 (114) |

2.32 (59) |

2.32 (59) |

50.56 (1,284) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 7.0 | 6.8 | 6.7 | 5.5 | 6.4 | 11.5 | 11.9 | 11.3 | 10.5 | 9.0 | 7.5 | 7.6 | 101.5 |

| Source: NOAA (mean maxima/minima 2006–2020)[35][36] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 119 | — | |

| 1890 | 287 | 141.2% | |

| 1900 | 543 | 89.2% | |

| 1910 | 1,121 | 106.4% | |

| 1920 | 2,007 | 79.0% | |

| 1930 | 4,149 | 106.7% | |

| 1940 | 4,402 | 6.1% | |

| 1950 | 5,775 | 31.2% | |

| 1960 | 8,781 | 52.1% | |

| 1970 | 10,580 | 20.5% | |

| 1980 | 13,557 | 28.1% | |

| 1990 | 16,543 | 22.0% | |

| 2000 | 20,048 | 21.2% | |

| 2010 | 22,464 | 12.1% | |

| 2020 | 30,142 | 34.2% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 32,655 | [6] | 8.3% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[37] 2020 Census[5] | |||

2020 census

edit| Race / Ethnicity | Pop 2000[38] | Pop 2010[39] | Pop 2020[40] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 18,141 | 19,951 | 25,900 | 90.5% | 88.81% | 85.93% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 1,250 | 1,307 | 1,176 | 6.3% | 5.82% | 3.90% |

| Native American or Alaska Native (NH) | 62 | 57 | 55 | 0.7% | 0.25% | 0.18% |

| Asian (NH) | 101 | 244 | 368 | % | 1.09% | 1.22% |

| Pacific Islander (NH) | 4 | 1 | 14 | 0.0% | 0.01% | 0.05% |

| Some Other Race (NH) | 14 | 9 | 101 | % | 0.04% | 0.34% |

| Mixed/Multi-Racial (NH) | 175 | 263 | 1,052 | 1.0% | 1.17% | 3.49% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 301 | 632 | 1,476 | 1.5% | 2.81% | 4.90% |

| Total | 20,048 | 22,464 | 30,142 | 100.0% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

As of the 2020 census, there were 30,142 people, 14,796 households, 8,544 families residing in the city.[41] The population density was 798.7 inhabitants per square mile (308.4/km2). There were 20,903 housing units. The racial makeup of the city was 87.4% White, 4.0% African American, 0.3% Native American, 1.2% Asian, 0.0% Pacific Islander, 1.2% from some other races and 5.8% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 4.9% of the population.[42]

The median income for a household in the city was $73,096. The per capita income for the city was $50,902.

2010 census

editAs of the 2010 census, there were 22,464 people, 11,074 households, and 6,322 families residing in the city. The population density was 648.4 inhabitants per square mile (250.3/km2). There were 16,847 housing units averaged 520.6 per square mile (201.0/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 90.8% White, 5.9% African American, 0.3% Native American, 1.1% Asian, 0.0% Pacific Islander, 0.5% from some other races and 1.4% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.8% of the population.

Of the 11,074 households, 14.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 44.1% were married couples living together, 9.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 42.9% were not families. About 35.3% of all households were made up of individuals, and 18.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.01 and the average family size was 2.54.

In the city, the population was distributed as 13.9% under the age of 18, 3.6% from 20 to 24, 17.9% from 25 to 44, 31.3% from 45 to 64, and 31.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 54.3 years. About 35.3% of all households were made up of individuals, and 18.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older.

The median income for a household in the city was $49,625, and for a family was $62,267. Males had a median income of $38,132 versus $32,087 for females. The per capita income for the city was $31,013. About 10.9% of families and 13.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 21.9% of those under age 18 and 8.3% of those aged 65 or over.

Education

editAll public education is run by Volusia County Schools.

Elementary schools

edit- Chisholm Elementary School

- Coronado Beach Elementary School

- Indian River Elementary School

- Read-Pattillo Elementary School

Middle school

edit- New Smyrna Beach Middle School

High school

editCharter school

edit- Burns Science and Technology (K-12)

Private School

edit- Sacred Heart School (private Catholic, K-8)

Higher education

edit- Daytona State College (New Smyrna Beach Campus)

Culture

editNamed one of "America's Top Small Cities for the Arts",[43] New Smyrna Beach is home to the Atlantic Center for the Arts, an artists-in-residence community and educational facility, the Harris House, the Little Theatre, and a gallery of fine arts, Arts on Douglas.

Popular amongst tourists, roosters roam the main street of the city, Flagler Avenue. They are thought to be a result of abandonment by locals (as only hens are permitted for personal use).[44]

The New Smyrna Speedway is a half-mile paved racetrack opened in 1967 that currently hosts the ARCA Menards Series East, NASCAR Whelen Modified Tour, Southern Super Series and World Series of Asphalt Stock Car Racing.[citation needed]

Shark attacks

editAccording to the International Shark Attack File maintained by the University of Florida, in 2007, Volusia County had more confirmed shark bites than any other region in the world.[45] Experts from the university have referred to the county as having the "dubious distinction as the world's shark-bite capital".[46] The trend continued in 2008, when the town broke its own record, with 24 shark bites.[47] An Orlando Sentinel photographer shot a picture of a four-foot spinner shark jumping over a surfer, a reversal of "jumping the shark".[48][49] Sharks bit three different surfers on September 18, 2016, in the span of a few hours at the same beach.[50] Very few of the shark bites are fatal.[51] In July 2024, two men and a 14-year-old boy were bitten in three separate attacks in less than one week.[52]

Government

editElected city government officials include:

- Fred Cleveland – Mayor

- Valli Perrine – Vice Mayor and Zone 1 Commissioner

- Lisa Martin – Zone 2 Commissioner

- Jason McGuirk – Zone 3 Commissioner

- Randy Hartman – Zone 4 Commissioner

Notable people

edit- Joseph Barbara, actor best known for the soap opera Another World

- Emory L. Bennett, United States Army soldier in the Korean War, Medal of Honor winner

- The Beu Sisters, music recording artists

- Joyce Cusack, Florida politician and retired registered nurse

- Suzanne Kosmas, Former U.S. Representative for Florida's 24th congressional district

- Jimmy McMillan, political activist, perennial candidate, Vietnam War veteran, and founder of the Rent is Too Damn High political party

- Walter M. Miller, Jr., author of A Canticle for Liebowitz

- Cory Mills, U.S. Representative for Florida's 7th congressional district (2023–present)

- Jack Mitchell, photographer and author of dance and iconic artist images

- Preston Pardus, American stock car racing driver

- Jim Parsley, American stock car racing driver

- Jacob Winchester, New York Times Critic's Pick award-winning composer, producer, writer, and director[53]

Athletes

edit- Dallas Baker, University of Florida alumnus, and professional football wide receiver, current assistant football coach at Buffalo Bulls

- Perry Baker, professional rugby player with the United States national rugby sevens team

- Laura Brown, former American college and professional golfer

- Wes Chandler, University of Florida alumnus, and professional football player in the NFL for 11 seasons during the 1970s and 1980s

- Eric Geiselman, professional surfer[54] with the world surf league[55]

- Chris Isaac, former quarterback with the Ottawa Rough Riders of the CFL

- Raheem Mostert, football running back and kickoff returner for the Miami Dolphins in the NFL

- Duffy Waldorf, professional golfer, former member of the PGA Tour who plays on the Champions Tour

Gallery

edit-

The Ocean House circa 1906

-

Bank corner in 1914

-

Battle-scarred tree in 1909

-

Whales on beach in 1908

-

City Hall

-

Cathedral oaks in 1909

References

edit- ^ "cygnus inter anates in English - Latin-English Dictionary | Glosbe". glosbe.com. Retrieved December 19, 2022.

- ^ "City Commission". City of New Smyrna Beach, Florida. September 1, 2024.

- ^ a b "2023 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 1, 2024.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: New Smyrna Beach, Florida

- ^ a b c "Explore Census Data". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 1, 2024.

- ^ a b c "City and Town Population Totals: 2020-2023". United States Census Bureau. August 19, 2024. Retrieved August 19, 2024.

- ^ "New Smyrna Beach (FL) sales tax rate". Retrieved September 1, 2024.

- ^ Surfer (April 5, 2009). "Best Surf Towns: No. 9 New Smyrna, Florida". Surfer Magazine. GrindMedia. Archived from the original on March 28, 2013. Retrieved November 14, 2013.

Smyrna Inlet is easily the most consistent break along Florida's 1,200+ miles of surfable coastline, and likely the most performance-friendly.

- ^ National Geographic Magazine. "World's 20 Best Surf Towns". National Geographic Adventure Trips. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved November 14, 2013.

- ^ Murphy, Paul P. (January 22, 2020). "Florida is the shark attack capital of the world, again". CNN. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ^ "Classical Latin: CYGNUS INTER ANATES". Latin R. Latinr.com.

English translations of common Latin phrases...

- ^ Moskos, Charles C. (2018). Greek Americans: Struggle and Success. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-51672-3.

- ^ Panagopoulos, E. P. (1956). "The Background of the Greek Settlers in the New Smyrna Colony". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 35 (2): 97. ISSN 0015-4113. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ Charles C. Moskos (January 1, 1989). Greek Americans: Struggle and Success. Transaction Publishers. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-4128-2483-5.

- ^ George Kaloudis (February 20, 2018). Modern Greece and the Diaspora Greeks in the United States. Lexington Books. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-4985-6228-7.

- ^ Kenneth Henry Beeson (2006). Fromajadas and Indigo: The Minorcan Colony in Florida. The History Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-59629-113-3.

- ^ Jane G. Landers (2000). Colonial Plantations and Economy in Florida. University Press of Florida. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-0-8130-1772-3.

- ^ Kenneth Henry Beeson (2006). Fromajadas and Indigo: The Minorcan Colony in Florida. The History Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-59629-113-3.

- ^ James W. Raab (November 5, 2007). Spain, Britain and the American Revolution in Florida, 1763–1783. McFarland. pp. 53–54. ISBN 978-0-7864-3213-4.

- ^ Bernard Romans (1776). A concise natural history of East and West-Florida. Pelican Publishing. pp. 268–270.

- ^ Federal Writers' Project (1939). Florida: A Guide to the Southern-Most State. US History Publishers. p. 543. ISBN 978-1-60354-009-4.

- ^ Patricia C. Griffin (1991). Mullet on the Beach: The Minorcans of Florida, 1768–1788. St. Augustine Historical Society. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-8130-1074-8.

- ^ Landers 2000, p. 62

- ^ Roger Grange, "Saving Eighteenth-Century New Smyrna: Public Archaeology in Action." Present Pasts vol 3 #1 (2011). online

- ^ ""Episode 08 European Earthenware" by Robert Cassanello and Chip Ford". stars.library.ucf.edu. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- ^ "The Saint Photios Greek Orthodox Chapel". St. Photios National Shrine. Archived from the original on December 2, 2013. Retrieved December 25, 2013.

- ^ Peter C. Moskos; Charles C. Moskos (November 27, 2013). Greek Americans: Struggle and Success. Transaction Publishers. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-4128-5310-1.

- ^ Coles, David J. (1988). Fretwell, Jacqueline K. (ed.). Civil War times in St. Augustine. Port Salerno, Fla.: Florida Classics Library. p. 78. ISBN 0912451238.

- ^ Redd, Robert (2014). St. Augustine and the Civil War (e-book ed.). Charleston, SC: The History Press. p. 22. ISBN 9781625846570.

- ^ Morschauser, Lindsey. "Florida, The Lightning Capital of the U.S." Campus Connect. Mississippi State University Weather. Retrieved June 22, 2021.

- ^ National Park Service. "Fire Management" (PDF). Canaveral National Seashore. U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- ^ "Year of hurricanes: Decade later, memories of Charley, Frances and Jeanne linger". Daytona Beach News-Journal Online. Retrieved October 10, 2024.

- ^ Carillo, Brenno. "1 year after Ian: A look back at the day of the storm and its aftermath". Daytona Beach News-Journal Online. Retrieved October 10, 2024.

- ^ Abbott, Jim. "After Milton's wrath, Volusia-Flagler picks up the pieces". Daytona Beach News-Journal Online. Retrieved October 10, 2024.

- ^ "NOWData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991-2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "P004: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – New Smyrna Beach city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – New Smyrna Beach city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – New Smyrna Beach city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "US Census Bureau, Table P16: Household Type". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 1, 2024.

- ^ "How many people live in New Smyrna Beach city, Florida". USA Today. Retrieved September 1, 2024.

- ^ "Surfscape Contemporary Dance Theatre". New Smyrna Beach Observer. October 13, 2012. Archived from the original on March 14, 2016. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

- ^ Korba, Nik (June 24, 2021). "'Rooster Gang' finds home on Flagler Avenue in New Smyrna Beach". Hometown News. Retrieved June 20, 2024.

- ^ ISAF 2007 Worldwide Shark Attack Summary (2007). "Death Total Lowest in Two Decades". International Shark Attack File. Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida. Archived from the original on October 7, 2013. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Cathy Keen; George Burgess (February 12, 2008). "Human deaths from shark attacks hit 20-year low last year" (PDF). University of Florida News. University of Florida. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 14, 2009. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

Within Florida, Volusia County continued its dubious distinction as the world's shark bite capital with 17 incidents, its highest yearly total since 2002, Burgess said.

- ^ Ludmilla Lelis (February 20, 2009). "Volusia again claims shark-bite record". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on March 1, 2010. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- ^ Ramsess, Akili C. (June 25, 2011), "Shark jumps over surfer at New Smyrna Beach", Florida360, Orlando Sentinel, retrieved June 28, 2011

- ^ Steinmetz, Katy (June 28, 2011), "Amazing Video: 'Spinner' Shark Flies Over Surfer", Newsfeed, Time, retrieved June 28, 2011

- ^ "3 surfers bitten by sharks at Florida beach". Fox News. September 19, 2016.

- ^ Brashear, Abigail (January 21, 2020), Shark bite capital: Volusia County still leads world as overall attacks decrease, Daytona Beach News-Journal, retrieved February 24, 2021

- ^ Sloan, Kaycee (July 8, 2024), "2 men hospitalized, 14-year-old injured in 3 separate shark attacks in Volusia County", wfla.com, retrieved December 5, 2024

- ^ "'Lula del Ray,' a Spectral Parade of Fantastical Images - The New York Times". The New York Times. October 7, 2024. Archived from the original on October 7, 2024. Retrieved November 17, 2024.

- ^ "Eric Geiselman - Official Website". ericgeiselman.com.

- ^ "Pro Surfer: Eric Geiselman".

Further reading

edit- Grange, Roger. "Saving Eighteenth-Century New Smyrnea: Public Archaeology in Action." Present Pasts vol 3 #1 (2011). online

- Panagopoulos, Epaminondas P. "The Background of the Greek Settlers in the New Smyrna Colony." Florida Historical Quarterly 35.2 (1956): 95–115. in JSTOR

- Panagopoulos, Epaminondas P. New Smyrna: An Eighteenth Century Greek Odyssey (University of Florida Press, 1966)

External links

edit- Official website

- New Smyrna Beach Regional Library

- New Smyrna Beach Museum of History

- Atlantic Center for the Arts

- New Smyrna Beach Area Visitors Bureau, official tourism information

- New Smyrna Beach tide information

- A History of Central Florida Podcast – European Earthenware, St. Benedict Medal, Print Culture