New Orleans rhythm and blues is a style of rhythm and blues that originated in New Orleans. It was a direct precursor to rock and roll and strongly influenced ska. Instrumentation typically includes drums, bass, piano, horns, electric guitar, and vocals. The style is characterized by syncopated "second line" rhythms, a strong backbeat, and soulful vocals. Artists such as Roy Brown, Dave Bartholomew, and Fats Domino are representative of the New Orleans R&B sound.[1]

| New Orleans rhythm and blues | |

|---|---|

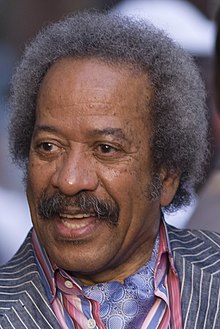

Allen Toussaint, noted New Orleans rhythm and blues artist, at a festival in New Orleans, 2009 | |

| Stylistic origins | |

| Cultural origins | New Orleans, United States |

Characteristics

editNew Orleans rhythm and blues can be characterized by predominant piano, "singing" horns, and call-and-response elements.[2] Clear influences of Kansas City Swing bands can be heard through the extensive use of trumpet and saxophone solos.[3] A "double" bass line, when the guitar and bass play in unison, was combined with a strong backbeat to make the music easy to dance to.[2] It is also common to hear the influence of Caribbean rhythms such as the mambo, rhumba, and the calypso.[4]

In addition, the usage of blue notes is characteristic. Like most blues, New Orleans R&B typically follows a standard three-stanza form that contains tonic, subdominant, and dominant chords. Within these chords, the three "blue notes", also known as flatted notes, are the third, fifth, and seventh scale degrees. In New Orleans R&B, the flatted third is particularly notable.[5]

Early pioneers

editNew Orleans rhythm and blues was pioneered by local barrelhouse pianists Champion Jack Dupree, Archibald, and Professor Longhair.

Professor Longhair, otherwise known as "Fess", was considerably influential in the development of the New Orleans R&B sound. Allen Toussaint, an important figure in New Orleans R&B, described him as "The Bach of Rock 'n' Roll".[6] He combined Caribbean and boogie-woogie rhythms to create his signature style. The result was a usage of polyrhythms that he often whistled while playing.[7] Although he was admired by other New Orleans musicians, he did not gain national attention until the end of his career.[8]

During his early career, Longhair visited the Caldonia Inn to listen to Dave Bartholomew's band. When he sat in for Bartholomew's pianist, a large crowd suddenly flooded the venue. He then decided to start his own band called the Four Hairs combo. Soon after, the band recorded their first four tunes at the Hi-Hat club for the Star Talent Label. In 1950, Longhair worked briefly with Mercury Records and recorded "Baldheaded". The song reached No.5 on Billboard's R&B chart. Due to financial complications, his work with Mercury was cut short. During the 1950s, he worked with Atlantic Records and recorded "Tipitina", which at the time was only a local hit, but today is recognized as a New Orleans R&B classic.[9]

Professors and barrelhouse pianists

editThere were two types of local pianists in New Orleans; "professor" pianists and "barrelhouse" pianists. Professors were often classically trained and understood music theory. They played in a variety of styles in the brothels of Storyville. Because they were more skilled, audiences expected them play any request that was thrown their way. Notable "professor" pianists include Buddy Christian, Clarence Williams, Alton Purnell, Spencer Williams, and Jelly Roll Morton. Barrelhouse pianists were often untrained with little to no background in music theory. They were mostly self-taught and played mostly in a blues style. Barrelhouse pianists were considered semi-professional and played for drinks, food, or tips.[10]

Popular artists

editRoy Brown, Dave Bartholomew, Paul Gayten, Smiley Lewis, Fats Domino, Annie Laurie, and Larry Darnell were the primary artists who achieved national fame.[11]

Roy Brown

editRoy Brown is considered to be one of the pioneers of the New Orleans Urban Blues as one of the first singers to blend elements of gospel into the blues. His "crying" sound became his signature.[12] In March 1947, Cecil Gant heard Brown sing "Good Rockin' Tonight" during a set break at a club called the Rainbow Room. Cecil enjoyed the song so much that he had Brown sing it over the phone for De Luxe Records.[13] Brown signed a contract with DeLuxe, and recorded the song at J&M Studio. "Good Rockin' Tonight" was an immediate success in New Orleans, and reached the national charts about one year later.[14] It became his biggest hit, and was successful enough for Brown and his band "The Mighty Men" to tour across California and the southwestern United States.[15] "Good Rockin' Tonight," made a reappearance in the charts in 1949 after DeLuxe was sold to King Records, who did their best to promote it, something that was not easy because at the time the word "rock" was a slang for "sex", which many people believed the song implied.[16] In 1950, Brown climbed his way up the charts once again with his song "Hard Luck Blues". Other popular tunes by Roy Brown include "Boogie at Midnight", "Love Don't Love Nobody", "Long About Sundown", "Cadillac Baby", "Party Doll", "Let the Four Winds Blow", and "Saturday Night".[17]

Dave Bartholomew

editDave Bartholomew was a bandleader and trumpet player. In the early stages of his career, between 1939 and 1942, he played on the SS Capitol riverboat with Fats Pichon. Toward the end of his residency, Pichon resigned to take a solo gig at the Old Absinthe House in New Orleans. Bartholomew took over the riverboat band until he was drafted in 1942. While serving in the army, he learned how to arrange music as a member of the 196th AGF band.[18] Upon discovering his passion for arranging and band leading, he was eager to return to New Orleans and make a name for himself.[19] In 1949, Bartholomew and his band recorded the hit song "Country Boy", while signed with DeLuxe. His true calling however, was to be involved with music production. He established himself as a band leader who arranged, produced, and scouted talent. During the 1950s, Bartholomew co-wrote most of the hits coming out of New Orleans.[20]

Paul Gayten

editPaul Gayten moved with his trio to New Orleans in his early twenties and established a residency at the Club Robin Hood. In 1947, his band recorded the two R&B hits "True (You Don't Love Me)" and "Since I Fell for You" with singer Annie Laurie for DeLuxe. When DeLuxe Records was bought out by King Records, the Braun brothers placed a new focus on Gayten's production skills. Soon after, he became the director for Chess Records.[21]

Smiley Lewis

editOverton Amos Lemons, also known as Smiley Lewis, was known for singing and playing guitar at nearly every venue in New Orleans early in his career. He had an extensive vocal range and a deep voice that could fill a room without any amplification. After the war, he formed a trio with Herman Seals and Tuts Washington. The two became very popular locally. While scouting for talent, the Braun brothers were impressed by Smiley and signed them to DeLuxe in 1947. Three years later, he signed to Imperial Records whom he worked with for ten years. He found moderate success with his songs "I Hear You Knockin'" and "The Bells Are Ringing".[22] He was overshadowed by Fats Domino who was also signed to Imperial and achieved national recognition for his cover of "I Hear You Knockin'".[23] Elvis Presley's hit "One Night (of Love)", was originally recorded by Lewis and was titled, "One Night (of Sin)". Similarly, Gale Storm's cover of "I Hear You Knockin'" made Billboard's Hot 100 Charts.[22]

Fats Domino

editIn 1949, Dave Bartholomew and Lew Chudd visited the Hideaway Club to listen to Fats Domino sing. They were impressed with his version of "Junkers Blues" and immediately signed him to Imperial Records.[24] That same year, Domino did his first recording session at the J&M studio under the direction of Dave Bartholomew. Of the eight songs that were cut during the session, "The Fat Man" was chosen as Domino's first big hit. A distinguishing element of the R&B hit was Domino's horn-like scat singing.[24]

Following the success of "The Fat Man", Domino toured with Jewel King and Dave Bartholomew's band. When his song "Goin' Home" reached number one in the R&B charts in 1952, his status as a star was confirmed.[25] The biggest hit of his career however, was "Blueberry Hill". Between the years of 1950 and 1955, he continued to make the R&B charts over a dozen times.[26] In 1956, he was the first black artist to make an appearance on the Steve Allen Show. He would later make appearances on the Perry Como Show, The Big Beat, and Dick Clark's American Bandstand.[27]

Domino's voice was a unique blend of creole intonations, nasal scat singing, and a warm tone.[25] He was known for using triplet piano figures in many of his songs. The "New Orleans" sound is heard in his cover of Smiley Lewis's "Blue Monday", with his combination of parade rhythms and barrelhouse blues.[28] Fats Domino was described by Dave Bartholomew as the "cornerstone" of Rock 'n' Roll.[29]

Notable record labels and producers

editCosimo Matassa

editCosimo Matassa was the leading record producer in New Orleans between 1940 and 1960. He created the "cosimo sound" with guitar, baritone saxophone, and tenor saxophone doubling the bass line. He also owned J&M Studio and Jazz City studio, where he recorded nearly all R&B hits in New Orleans between 1940-1960.[30]

DeLuxe Records

editDavid and Julian Braun, also known as the Braun brothers, owned an independent record label called "DeLuxe" which was based in Linden, New Jersey. Seeing that New Orleans was overflowing with talent, they decided to visit the city in 1947 with hopes of signing some new artists.[31] DeLuxe signed Dave Bartholomew, Paul Gayten, Smiley Lewis, Roy Brown, and Annie Laurie. In 1949 DeLuxe Records was bought out by Syd Nathan, owner of King Records.[16]

Imperial Records

editLew Chudd founded Imperial Records in 1947. During its early years, the label centered around country music and west coast jump bands. Looking to expand his business, Chudd reached out to Dave Bartholomew. They decided that they would work together and explore the up-and-coming R&B scene. They recorded their first R&B studio session with Jewel King and Tommy Ridgley at J&M studio.[32]

References

edit- ^ McKnight Mark, "Researching New Orleans Rhythm and Blues," Black Music Research Journal 8/1 (1988), p. 115

- ^ a b Jason Berry, Jonathon Foose, and Tad Jones, Up From the Cradle of Jazz (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1986), p. 5, ISBN 9780820308548

- ^ Gérard Herzhaft, Encyclopedia of the Blues, trans. Brigette Debord (Fayetville: University of Arkansas Press, 1997), p. 154, ISBN 978-1-55728-452-5

- ^ Berry, Foose, and Jones, Up From the Cradle of Jazz, p. 20

- ^ Berry, Foose, and Jones, Up From the Cradle of Jazz, p. 70

- ^ John Broven, Rhythm and Blues in New Orleans (Gretna: Pelican, 1974), p. 4, ISBN 978-1455619511

- ^ McKnight, "Researching New Orleans Rhythm and Blues," p. 115

- ^ McKnight, "Researching New Orleans Rhythm and Blues," p. 117

- ^ Broven, Rhythm and Blues in New Orleans, p. 7

- ^ Jeff Hannusch, I Hear You Knockin' (Ville Platte: Swallow, 1987), p. 3, ISBN 978-0961424503

- ^ John Broven, "Appendix," in Rhythm and Blues in New Orleans (Gretna: Pelican, 1974), pp. 228-237

- ^ Hannusch, I Hear You Knockin' , p. 71

- ^ Hannusch, I Hear You Knockin' , p. 74

- ^ Broven, Rhythm and Blues in New Orleans, p. 21

- ^ Herzhaft, Encyclopedia of the Blues, p. 27

- ^ a b Broven, Rhythm and Blues in New Orleans, p. 23

- ^ Broven, Rhythm and Blues in New Orleans, p. 24

- ^ Broven, Rhythm and Blues in New Orleans, p. 19

- ^ Broven, Rhythm and Blues in New Orleans, p. 18

- ^ Herzhaft, Encyclopedia of the Blues, pp. 154-155

- ^ Berry, Foose, and Jones, Up From the Cradle of Jazz, p. 76

- ^ a b Broven, Rhythm and Blues in New Orleans, p. 34

- ^ Berry, Foose, and Jones, Up From the Cradle of Jazz, pp. 72-74.

- ^ a b Berry, Foose, and Jones, Up From the Cradle of Jazz, p. 34

- ^ a b Broven, Rhythm and Blues in New Orleans, p. 32

- ^ Berry, Foose, and Jones, Up From the Cradle of Jazz, p. 36

- ^ Berry, Foose, and Jones, Up From the Cradle of Jazz, pp. 35-36

- ^ Rick Coleman, Blue Monday: Fats Domino and the Lost Dawn of Rock 'n' Roll (Boston: Da Capo, 2006), p. 8, ISBN 978-0306815317

- ^ Coleman, Blue Monday: Fats Domino and the Lost Dawn of Rock 'n' Roll, p. XVI

- ^ Broven, Rhythm and Blues in New Orleans, p. 13

- ^ Broven, Rhythm and Blues in New Orleans, p. 17

- ^ Broven, Rhythm and Blues in New Orleans, pp. 25-27