Neminātha (Devanagari: नेमिनाथ) (Sanskrit: नेमिनाथः), also known as Nemi and Ariṣṭanemi (Devanagari: अरिष्टनेमि), is the twenty-second tirthankara of Jainism in the present age (Avasarpini). Neminath lived 81,000 years before the 23rd Tirthankar Parshvanath. According to traditional accounts, he was born to King Samudravijaya and Queen Shivadevi of the Yadu dynasty in the north Indian city of Sauripura. His birth date was the fifth day of Shravan Shukla of the Jain calendar. Balarama and Krishna, who were the 9th and last Baladeva and Vasudeva respectively, were his first cousins.

| Neminath | |

|---|---|

22nd Tirthankara | |

| Member of Tirthankar, Salakapurusha, Arihant and Siddha | |

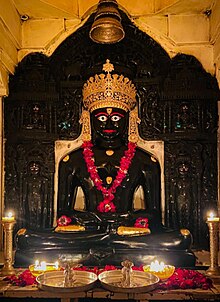

Idol of Neminath at Girnar Hill, Gujarat | |

| Other names | Nemi, Nem |

| Venerated in | Jainism |

| Predecessor | Naminatha |

| Successor | Parshvanatha |

| Symbol | Shankha (conch) [1] |

| Height | 10 bows – 98 feet (30 m)[2] |

| Age | 1000 |

| Color | Black |

| Gender | Male |

| Genealogy | |

| Born | Ariṣṭanemi |

| Died | |

| Parents |

|

| Dynasty | Yadu clan [3][4] |

Neminatha, when heard the cries of animals being killed for his marriage feast, freed the animals and renounced his worldly life and became a Jain ascetic. The representatives of this event are popular in Jain art. He had attained moksha on Girnar Hills near Junagadh, and became a siddha, a liberated soul which has destroyed all of its karma.

Along with Mahavira, Parshvanatha and Rishabhanatha, Neminath is one of the twenty-four Tirthankars who attract the most devotional worship among the Jains. His icons include the eponymous deer as his emblem, the Mahavenu tree, Sarvanha (Digambara) or Gomedha (Śhvētāmbara) Yaksha, and Ambika Yakshi.

Nomenclature

editThe name Neminatha consists of two Sanskrit words, Nemi which means "rim, felly of a wheel" or alternatively "thunderbolt",[5] and natha which means "lord, patron, protector".[6]

According to the Jain text Uttarapurana, as well as the explanation of Acharya Hemchandra, it was the ancient Indian deity Indra who named the 22nd tirthankara as Neminatha, because he viewed the Jina as the "rim of the wheel of dharma".[7]

In Śvetāmbara Jain texts, his name Aristanemi came from a dream his mother had during pregnancy, where she saw a "wheel of Arista jewels".[8] His full name is mentioned as Aristanemi which is an epithet of the sun-chariot.[9][10] Neminatha's name is spelled close to the 21st tirthankara Naminatha.[11]

Life

editNeminatha was the twenty-second Tirthankara (ford-maker) of the avasarpiṇī (present descending cycle of Jain cosmology).[12][13][14] Jain tradition place him as a contemporary of Krishna, the ninth and last vasudev.[15] There was a gap of 581,750 years between the Neminatha and his predecessor, Naminatha as per traditional beliefs.[16][11] He lived approx. 81,000 years before the 23rd Tirthankara, Parshvanatha as per the Trishashtishalakapursusha Charitra of Acharya Hemachandra.[16]

Birth

editNeminatha is mentioned as the youngest son of king Samudravijaya and queen Shivadevi of the Yadu lineage,[3][4] born at Sauripura (Dvaraka).[17] He is believed to have become fond of animals in his early life due to being in a cattle-herding family. Jain legends place him in the Girnar-Kathiawad (in Saurashtra region of modern-day Gujarat).[18][19][20] His birth date is believed to be the fifth day of Shravana Shukla of the Hindu calendar.[14]

Life before renunciation

editHe is believed to have been born with a dark-blue skin complexion,[22] a very handsome but shy young man.[4][17] His father is mentioned as the brother of Vasudeva, Krishna's father, therefore he is mentioned as the cousin of Krishna in Trishashti-salaka-purusha-charitra.[12][23][21][24][25][26] Sculptures found in Kankali Tila, Mathura of Kushana period depicts Krishna and Balarama as cousins of Neminatha.[27]

In one of the legends, on being taunted by Satyabhama, wife of Krishna, Neminatha is depicted to have blown Panchajanya, the mighty conch of Krishna through his nostrils. According to the texts, no one could lift the conch except Krishna, let alone blow it.[28][17] After this event, the Harivaṃśapurāṇa, as composed by Acharya Jinasena, states that Krishna decided to test Neminatha's strength and challenged him for a friendly duel. Neminatha, being a Tirthankara, is believed to have defeated Krishna easily.[29] He is also mentioned as spinning a great Chakra with the right leg toe during his childhood.[17]

As a teacher

editIn the war between Krishna and Jarasandha, Neminatha is believed to have participated alongside Krishna.[30] This is believed to be the reason for celebrating Krishna-related festivals in Jainism and for intermingling with Hindus, who worship Krishna as one of the incarnations of Vishnu.[31]

Chandogya Upanishad, a religious text in Hinduism, mentions Angiras Ghora as the teacher of Krishna.[15] He is believed to have taught Krishna the five vows, namely, honesty, asceticism, charity, non-violence and truthfulness. Ghora is identified as Neminatha by some scholars.[15] Mahabharata mentions him as the teacher of the path of salvation to king Sagara. He may also be identified with a Scandinavian or Chinese deity, but such claims are not accepted generally.[32]

Renunciation

editJain tradition holds that the Neminatha's marriage was arranged with Rajulakumari or Rajimati or Rajamati, daughter of Ugrasena.[28][17] Ugrasena is believed to be the king of Dvārakā and maternal grandfather of Krishna.[17] He is believed to have heard animal cries as they were being slaughtered for the marriage feast. Taken over by sorrow and distress at the sight, he is believed to have given up the desire of getting married, and to have become a monk and gone to Mount Girnar.[12][33][34][24][11] His bride-to-be Rajulakumari is believed to have followed him, becoming a nun and his brother Rahanemi became a monk, joining his ascetic order.[17][25][28]

According to Kalpasutras, Neminatha led an ascetic life thereby eating only once every three days,[35] meditated for 55 days and then obtained omniscience on Mount Raivataka, under a Mahavenu tree.[22]

Disciples

editAccording to Jain texts Neminatha had 11 Gandhara with Varadatta Svami as the leader of the Neminatha disciples.[36] Neminatha's sangha (religious order) consisted of 18,000 sadhus (male monks) and 44,000 sadhvis (female monks) as per the mentions in Kalpa Sutra.[37]

Nirvana

editHe is said to have lived 1,000 years[38] and spent many years spreading his knowledge and preaching principles of ahiṃsā (non-violence) and aparigraha (asceticism) in the Saurashtra region.[39] He is said to have attained moksha (nirvana) on the fifth peak or tonk (Urjayant Parvat) of Mount Girnar.[25][36][12] Of these 1,000 years, he is believed to have spent 300 years as a bachelor, 54 days as an ascetic monk and 700 years as an omniscient being.[35]

The yaksha and yakshi of Neminatha are Sarvanha (Digambara) or Gomedha (Śhvētāmbara) Yaksha, and Ambika Yakshi.[36]

Legacy

editWorship

editAlong with Mahavira, Parshvanatha and Rishabhanatha, Neminatha is one of the twenty-four Tirthankaras who attract the most devotional worship among the Jains.[40] Unlike the last two tirthankaras, historians consider Neminatha and all other tirthankaras to be legendary characters.[12] Scenes from Neminatha's life are popular in Jain art.[36] Jinastotrāņi is a collection of hymn dedicated to Neminatha along with Munisuvrata, Chandraprabha, Shantinatha, Mahavira, Parshvanatha and Rishabhanatha.[41]

The yaksha and yakshi of Neminatha are Sarvanha and Ambika according to Digambara tradition and Gomedha and Ambika according to Śhvētāmbara tradition.[36]

Samantabhadra's Svayambhustotra praises the twenty-four tirthankaras, and its eight shlokas (songs) adore Shantinatha.[42] One such shloka reads:

O Worshipful Lord! Endowed with supreme accomplishments, you had burnt the karmic fuel with the help of pure concentration; your eyes were broad as open water-lilies. You were the chief of the Hari dynasty and had promulgated the unblemished tradition of reverence, and control of the senses. You were an ocean of right conduct, and ageless. O Most Excellent Lord Ariṣṭanemi! After illuminating the world (the universe and the non-universe) through powerful ways of omniscience, you had attained liberation

— Svayambhūstotra (22-1-121)[43]

Literature

editThe Jain traditions about Neminatha are incorporated in the Harivamsa Purana of Jinasena.[44][45] A palm leaf manuscript on the life of Neminatha, named Neminatha-Charitra, was written in 1198-1142 AD. It is now preserved in Shantinatha Bhandara, Khambhat.[46] The incident where Neminatha is depicted as blowing Krishna's mighty conch is given in Kalpa Sūtra.[9]

Rajul's love for Neminatha is described in the Rajal-Barahmasa (an early 14th-century poem of Vijayachandrasuri).[47] The separation of Rajul and Neminatha has been a popular theme among Jain poets who composed Gujarati fagus, a poetry genre. Some examples are Neminatha Fagu (1344) by Rajshekhar, Neminatha Fagu (1375) by Jayashekhar and Rangasagara Neminatha Fagu (1400) by Somsundar. The poem Neminatha Chatushpadika (1269) by Vinaychandra depicted the same story.[48][49][50][51][52]

Arddha Nemi, the "Unfinished Life of Nemi", is an incomplete epic by Janna, one of the most influential Kannada poets of the 13th century.[53][54] Nemidutam composed by Acharya Jinasena, 9th century, is an adoration of Neminatha.[55]

Neminatha, along with Rishbhanatha and the Śramaṇa tradition, has been mentioned in the Rigveda. Neminatha is also referred to in Yajurveda.[56][57]

Iconography

editNeminatha is believed to have had the same dark-bluish-colored skin as Krishna.[58] Painting depicting his life stories generally identifies him as dark-coloured. His iconographic identifier is a conch carved or stamped below his statues. Sometimes, as with Vishnu's iconography, a chakra is also shown near him, as in the 6th-century sculpture found at the archaeological site near Padhavali (Madhya Pradesh).[59] Artworks showing Neminatha sometimes include Ambika yakshi, but her colour varies from golden to greenish to dark-blue, by region.[60]

The earliest known image of Neminatha was found in Kankali Tila dating back to c. 18 CE.[61]

-

Neminatha Jain statue (c. 475 CE), in Buddha style from Shreyansh giri

-

Neminatha, Nasik Caves, 6th century

-

Akota Bronzes, MET museum, 7th century

-

Image at Maharaja Chhatrasal Museum, 12th century

-

Neminath idol, Government Museum, Mathura, 12th Century

-

Depiction of Neminatha on Naag as bed, chakra on foot finger and conch played by nose at Parshvanath temple, Tijara

Temples

editNeminatha is one of the five most devotionally revered Tirthankaras, along with Mahavira, Rishabhanatha, Parshvanatha and Shantinatha.[40] Various Jain temple complexes across India feature him, and these are important pilgrimage sites in Jainism. Mount Girnar of Gujarat, for example, which is believed to have been a place where Neminatha is believed to have achieved nirvana.[62]

Luna Vasahi in Dilwara Temples, built in 1230 by two Porwad brothers - Vastupala and Tejpal, considered famous for ellaborate architecture and intricate carvings.[63] The ceilings of the temple depicts scenes of the life of Neminatha with image of Rajmathi (who was to marry Neminatha)[64] and Krishna.[65][36] Shanka Basadi in Lakshmeshwara, built in 7th century, is considered one of the most important temple built by Kalyani Chalukyas.[66] The temple derives its name from the image of Neminatha in kayotsarga posture standing on a large shankha (conch shell).[64] The unique feature of this temple is a monolithic pillar with the carving of 1008 Tirthankaras known as Sahasrakuta Jinabimba.[67][68] Adikavi Pampa wrote Ādi purāṇa, seated in this basadi (temple) during 9th century.[69][70]

Important Neminatha temple complexes include Tirumalai (Jain complex), Kulpakji, Arahanthgiri Jain Math, Nemgiri, Bhand Dewal, Bhand Dewal in Arang and Odegal basadi.

See also

editReferences

editCitations

edit- ^ Tandon 2002, p. 45.

- ^ Sarasvati 1970, p. 444.

- ^ a b von Glasenapp 1925, p. 317.

- ^ a b c Doniger 1993, p. 225.

- ^ Monier Williams, p. 569.

- ^ Monier Williams, p. 534.

- ^ Umakant P. Shah 1987.

- ^ Umakant P. Shah 1987, pp. 164–165.

- ^ a b Jain & Fischer 1978, p. 17.

- ^ Zimmer 1953, p. 225.

- ^ a b c von Glasenapp 1925, pp. 317–318.

- ^ a b c d e "Arishtanemi: Jaina saint". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- ^ Zimmer 1953, p. 224.

- ^ a b Tukol 1980, p. 31.

- ^ a b c Natubhai Shah 2004, p. 23.

- ^ a b Zimmer 1953, p. 226.

- ^ a b c d e f g Natubhai Shah 2004, p. 24.

- ^ Dhere 2011, pp. 193–196.

- ^ Upinder Singh 2008, p. 313.

- ^ Cort 2001, p. 23.

- ^ a b Jain & Fischer 1978, pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b Umakant P. Shah 1987, p. 164.

- ^ Johnson 1931, pp. 1–266.

- ^ a b Umakant P. Shah 1987, pp. 165–166.

- ^ a b c Sangave 2001, p. 104.

- ^ Gaur 1976, p. 46.

- ^ Vyas 1995, p. 19.

- ^ a b c von Glasenapp 1925, p. 318.

- ^ Doniger 1993, p. 226.

- ^ Beck 2012, p. 156.

- ^ Long 2009, p. 42.

- ^ Natubhai Shah 2004, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Sehdev Kumar 2001, pp. 143–145.

- ^ Kailash Chand Jain 1991, p. 7.

- ^ a b Jones & Ryan 2006, p. 311.

- ^ a b c d e f Umakant P. Shah 1987, p. 165.

- ^ Cort 2001, p. 47.

- ^ Melton & Baumann 2010, p. 1551.

- ^ Natubhai Shah 2004, p. 25.

- ^ a b Dundas 2002, p. 40.

- ^ Lienhard 1984, p. 137.

- ^ Jain 2015, pp. 150–155.

- ^ Jain 2015, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Umakant P. Shah 1987, p. 239.

- ^ Upinder Singh 2016, p. 26.

- ^ Umakant P. Shah 1987, p. 253.

- ^ Kelting 2009, p. 117.

- ^ Amaresh Datta 1988, p. 1258.

- ^ K. K. Shastree 2002, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Nagendra 1988, pp. 282–283.

- ^ Jhaveri 1978, pp. 14, 242–243.

- ^ Parul Shah 1983, pp. 134–156.

- ^ Rice 1982, p. 43.

- ^ Sastri 2002, pp. 358–359.

- ^ Acharya Charantirtha 1973, p. 47.

- ^ Natubhai Shah 2004, p. 269.

- ^ Reddy 2023, p. 187.

- ^ Umakant P. Shah 1987, pp. 164–168.

- ^ Umakant P. Shah 1987, pp. 164–170.

- ^ Umakant P. Shah 1987, pp. 264–265.

- ^ Umakant P. Shah 1987, p. 166.

- ^ Cort 2001, p. 229.

- ^ Ching, Jarzombek & Prakash 2010, p. 336.

- ^ a b Umakant P. Shah 1987, p. 169.

- ^ Titze & Bruhn 1998, p. 253.

- ^ Chugh 2016, p. 300.

- ^ Chugh 2016, p. 295.

- ^ Chugh 2016, pp. 305–306.

- ^ Azer 2011.

- ^ Chugh 2016, p. 437.

Sources

editBooks

edit- Beck, Guy L. (1 February 2012), Alternative Krishnas: Regional and Vernacular Variations on a Hindu Deity, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-6415-1

- Cort, John E. (2001), Jains in the World: Religious Values and Ideology in India, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-803037-9

- Ching, Francis D. K.; Jarzombek, Mark M.; Prakash, Vikramaditya (2010) [1934], A Global History of Architecture, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-471-26892-5

- Chugh, Lalit (2016). Karnataka's Rich Heritage - Art and Architecture (From Prehistoric Times to the Hoysala Period ed.). Chennai: Notion Press. ISBN 978-93-5206-825-8.

- Acharya Charantirtha (1973). Meghadutam of Mahakavi Kalidas. Chaukhamba Sanskrit Series. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Surbharati Prakashan.

- Datta, Amaresh (1988), Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature, Sahitya Akademi, ISBN 978-81-260-1194-0

- Dhere, Ramchandra C. (2011), Rise of a Folk God: Vitthal of Pandharpur, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-977759-4

- Dundas, Paul (2002) [1992], The Jains (Second ed.), Routledge, ISBN 0-415-26605-X

- Doniger, Wendy (1993), Purana Perennis: Reciprocity and Transformation in Hindu and Jaina Texts, SUNY Press, ISBN 0-7914-1381-0

- Jain, Jyotindra; Fischer, Eberhard (1978), Jaina Iconography, vol. 12, Brill Publishers, ISBN 978-90-04-05259-8

- Jain, Kailash Chand (1991), Lord Mahāvīra and His Times, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0805-8

- Jain, Vijay K. (2015), Acarya Samantabhadra's Svayambhustotra: Adoration of The Twenty-four Tirthankara, Vikalp Printer, ISBN 9788190363976,

Non-Copyright

- Jhaveri, Mansukhlal (1978), History of Gujarati Literature, Sahitya Akademi, archived from the original on 20 December 2016

- Johnson, Helen M. (1931), Neminathacaritra (Book 8 of the Trishashti Shalaka Purusha Caritra), Baroda Oriental Institute

- Jones, Constance; Ryan, James D. (2006), Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8160-7564-5

- Kelting, M. Whitney (2009), Heroic Wives Rituals, Stories and the Virtues of Jain Wifehood, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-538964-7

- Kumar, Sehdev (2001), A Thousand Petalled Lotus: Jain Temples of Rajasthan : Architecture & Iconography, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 978-81-7017-348-9

- Long, Jeffery D. (2009), Jainism: An Introduction, I. B. Tauris, ISBN 978-1-84511-625-5

- Lienhard, Siegfried (1984), A History of Classical Poetry: Sanskrit, Pali, Prakrit, A history of Indian literature: Classical Sanskrit literature, vol. 1, Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-1-84511-625-5

- Melton, J. Gordon; Baumann, Martin, eds. (2010), Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices, vol. One: A-B (Second ed.), ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-59884-204-3

- Nagendra (1988), Indian Literature, Prabhat Prakashan

- Rice, E.P. (1982) [1921]. A History of Kanarese Literature. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-0063-0.

- Reddy, P. Chenny (2023). Kalyana Mitra: A treasure house of history, culture and archaeological studies. Vol. 5. Blue Rose Publishers. ISBN 978-93-5741-111-0.

- Sangave, Vilas Adinath (2001), Facets of Jainology: Selected Research Papers on Jain Society, Religion, and Culture, Mumbai: Popular Prakashan, ISBN 978-81-7154-839-2

- Sarasvati, Swami Dayananda (1970), An English translation of the Satyarth Prakash, Swami Dayananda Sarasvati[permanent dead link]

- Shah, Natubhai (2004), Jainism: The World of Conquerors, vol. 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 9788120819382

- Shah, Parul (31 August 1983), "5", The rasa dance of Gujarata (Ph.D.), vol. 1, Department of Dance, Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, hdl:10603/59446

- Shastree, K. K. (2002), Gujarat Darsana: The Literary History, Darshan Trust, Ahmedabad

- Singh, Upinder (2016), A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, Pearson Education, ISBN 978-93-325-6996-6

- Shah, Umakant Premanand (1987), Jaina-rūpa-maṇḍana: Jaina iconography, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 81-7017-208-X

- Sastri, K.A. Nilakanta (2002) [1955]. A history of South India from prehistoric times to the fall of Vijayanagar. New Delhi: Indian Branch, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-560686-8.

- Singh, Upinder (2008), A history of ancient and early medieval India : from the Stone Age to the 12th century, New Delhi: Pearson Education, ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0

- Tandon, Om Prakash (2002) [1968], Jaina Shrines in India (1 ed.), New Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India, ISBN 81-230-1013-3

- Titze, Kurt; Bruhn, Klaus (1998). Jainism: A Pictorial Guide to the Religion of Non-Violence (2 ed.). Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1534-6.

- Tukol, T. K. (1980), Compendium of Jainism, Dharwad: University of Karnataka

- von Glasenapp, Helmuth (1925), Jainism: An Indian Religion of Salvation [Der Jainismus: Eine Indische Erlosungsreligion], Shridhar B. Shrotri (trans.), Motilal Banarsidass (Reprint: 1999), ISBN 81-208-1376-6

- Vyas, Dr. R. T., ed. (1995), Studies in Jaina Art and Iconography and Allied Subjects, The Director, Oriental Institute, on behalf of the Registrar, M.S. University of Baroda, Vadodara, ISBN 81-7017-316-7

- Williams, Monier, Nemi - Sanskrit English Dictionary with Etymology, Oxford University Press

- Zimmer, Heinrich (1953) [April 1952], Campbell, Joseph (ed.), Philosophies Of India, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, ISBN 978-81-208-0739-6,

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

Web

edit- Gaur, R. C. (1976). "Vedoc Chronology". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 37. Indian History Congress: 46–49. JSTOR 44138897. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- Azer, Rahman (27 June 2011). "Lakshmeshwar, a melting pot of cultures". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 9 May 2021.