The Washington Navy Yard (WNY) is a ceremonial and administrative center for the United States Navy, located in the federal national capital city of Washington, D.C. (federal District of Columbia). It is the oldest shore establishment / base of the United States Navy, established 1799, situated along the north shore of the Anacostia River (Eastern Branch of the Potomac River) in the adjacent Navy Yard neighborhood of Southeast, Washington, D.C.

| Washington Navy Yard | |

|---|---|

| Part of Naval Support Activity Washington | |

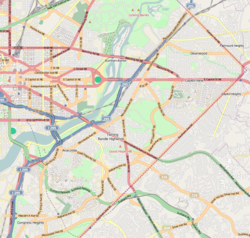

| Southeast Washington, D.C. in the United States | |

An aerial view of the Washington Navy Yard (established 1799), on the confluence of the Anacostia River (Eastern Branch) of the Potomac River, during 2021 | |

| |

| Coordinates | 38°52′24″N 76°59′49″W / 38.87333°N 76.99694°W |

| Type | Naval support base |

| Site information | |

| Owner | U.S. Department of Defense (1947 to present) U.S. Department of the Navy (1799-1947) |

| Operator | United States Navy |

| Controlled by | Naval District Washington |

| Condition | Operational |

| Website | Official website |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1799 |

| In use | 1799 – present |

| Events |

|

| Garrison information | |

| Current commander | CAPTAIN Mark C. Burns |

| Official name | Washington Navy Yard |

| Designated | 19 June 1973 |

| Designated | 11 May 1976 |

| Reference no. | 73002124 |

| Areas of significance |

|

| Architect | Benjamin Latrobe et al. |

| Architect | |

| Designated | 8 November 1964[1] |

Formerly operating as a shipyard since the end of the 18th century / beginning of the 19th century, and ordnance plant, the yard currently serves as home to the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO), commanding the U.S. Navy, and is headquarters for the several military agencies and commands of: Naval Sea Systems Command, Naval Reactors, Naval Facilities Engineering Systems Command, Naval History and Heritage Command, Navy Installations Command, the National Museum of the United States Navy, the U.S. Navy Judge Advocate General's Corps, Marine Corps Institute, the United States Navy Band, and other more classified facilities.

In 1998, the yard was also listed as a Superfund site by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency due to the extreme environmental contamination over its two and a quarter centuries existence.[2]

History

editThe history of the Washington Navy Yard in Washington , D.C. can be divided into its military history and parallel cultural and scientific history.

Military

editThe land along the north shore of the Eastern Branch (now called the Anacostia River) of the Potomac River in the newly laid-out federal capital city in the District of Columbia, later called Washington city, was purchased under an Act of Congress on July 23, 1799. The Washington Navy Yard was then established two and half months later on October 2, 1799, the date the property was transferred to the also newly-established United States Department of the Navy. It is the oldest shore establishment of the United States Navy. The Yard was built under the direction of Benjamin Stoddert (1751-1813, served 1798-1801), as the first U.S. Secretary of the Navy, and heading the also new U.S. Department of the Navy in the presidential administration of the second President, John Adams (1735-1826, served 1797-1801), under the supervision of the Yard's first commandant, Commodore Thomas Tingey (1750-1829), who served in that capacity for the following 29 years to 1828.

The original boundaries that were established in 1800, along 9th and M Street SE, are still marked by a white painted brick wall that surrounds the Yard on the north and east landward sides. The following year, two additional lots were purchased. The north wall of the Yard was built in 1809 along with a guardhouse structure, now known as the Latrobe Gate (named for Yard and U.S. Capitol architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe (1764-1820). After the Burning of Washington during the British Army invasion and attack during the War of 1812 (1812-1815), in August 1814, Commodore Tingey recommended that the height of the eastern wall be increased to ten feet (3 m) because of the experience of the fire and subsequent looting that occurred by not only British soldiers, but unfortunately also local American residents.

The southern boundary of the Yard was formed by the Anacostia River (then called the "Eastern Branch" of the Potomac River). The west side was undeveloped shoreline marsh. The land located along the Anacostia was gradually added to by landfill over the years as it became necessary to increase the size of the Yard.

From its first years, the Washington Navy Yard became the Navy's largest shipbuilding and shipfitting facility, with 22 vessels and warships constructed there, ranging from small 70-foot (21 m) gunboats to the 246-foot (75 m) steam frigate U.S.S. Minnesota. The U.S.F. Constitution came to the Yard in 1812 to refit and prepare for possible overseas combat action after the declaration of war by Congress in June 1812.

During the War of 1812, the Navy Yard was important not only as a support facility but also as a vital strategic link in defense of the federal capital city. Sailors of the Navy Yard were part of the hastily assembled American militia army, which, at the tragic defeat at the August 1814 Battle of Bladensburg in Bladensburg, Maryland, northeast outside the District of Columbia capital, opposing the British Army invading forces marching overland on Washington, after landing further east at Benedict, Maryland, having sailed portions of their Royal Navy fleet up the nearby Patuxent River from the Chesapeake Bay.

An independent volunteer militia rifle company of civilian workers in the Washington Navy Yard was organized by the United States naval architect William Doughty (1773-1859), earlier in 1813, and they regularly drilled after working hours. In 1814, Captain Doughty's volunteers were designated as the Navy Yard Rifles and assigned to serve under the overall command of Major Robert Brent (1764-1819, served 1802-1812), commanding the 2nd Regiment of the District of Columbia Militia (who was also the first mayor of Washington City 1802-1812, in the federal capital city in the District of Columbia under its first municipal government in the 19th century). In late August, they were ordered to March to the northeast and assemble at Bladensburg, Maryland, to form the first line of defense in protecting the United States' capital city along with the majority of the American forces was ordered to retreat.[3] The seamen of the Chesapeake Bay Flotilla of Commodore Joshua Barney (1759-1818), also joined the combined forces of Navy Yard sailors, and the U.S. Marines from the nearby Marine Barracks of Washington, D.C., and were positioned to be the third and final line of the American defenses along the stream bank of the upper Anacostia River and across the bridge there. Together, they effectively used devastating artillery / cannon fire and finally fought in hand-to-hand combat with cutlasses and pikes against the British Redcoats regulars before being overwhelmed. Benjamin King (1764-1840), a Navy Yard civilian master blacksmith, fought at Bladensburg. King accompanied Captain Miller's Marines into battle. King took charge of a disabled gun and was instrumental in bringing that gun into action. Captain Miller remembered King's gun "cut down sixteen of the enemy."[4][5]

As the British Army marched into Washington, holding the Yard became impossible. Seeing the smoke from the burning fire at the under-construction, unfinished United States Capitol on Capitol Hill, Commodore Tingey then ordered the Yard facilities also be burned to prevent its capture and use by the enemy. Both structures are now individually listed on the National Register of Historic Places (lists maintained by the National Park Service of the United States Department of the Interior). On August 30, 1814, Mary Stockton Hunter, an eyewitness to the vast fiery conflagration, wrote a letter to her sister, saying: "No pen can describe the appalling sound that our ears heard and the sight our eyes saw. We could see everything from the upper part of our house as plainly as if we had been in the Yard. All the vessels of war on fire-the immense quantity of dry timber, together with the houses and stores in flames produced an almost meridian brightness. You never saw a drawing room so brilliantly lighted as the whole city was that night."[6]

Among the vessels that were burned at the Yard were two warships under construction and nearing completion: the original Columbia, a 44-gun frigate, and the Argus, an 18-gun brig being built to replace an earlier Argus, which had been captured by the British a year earlier following a fierce engagement off the coast of Wales in the British Isles.[7]

Civilian employment

editFrom its beginning, the Navy Yard had one of the biggest payrolls in town, with the number of civilian mechanics and laborers and contractors expanding with the seasons and the naval Congressional appropriation.[8]

Before the passage of the Pendleton Act on 16 January 1883, applications for employment at the Washington Navy Yard were informal, mainly based on connections, patronage, and personal influence. An example from 1806 is the employment of Winthrop and Samuel Shriggins, two ship carpenters who were hired at $2.06 per diem, 12 March 1806 based on the approval of later second U.S. Secretary of the Navy, Robert Smith (1757-1842, served 1801-1809) under the two terms of presidential administration of third President, Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826, served 1801-1809). While a former seaman, Adam Keizer, was hired because he "was with Captain / Commodore William Bainbridge (1774-1833), at Tripoli."[9][10] On occasion, a dearth of applicants required a public announcement; the first such documented advertisement was by Commodore Thomas Tingey on 15 May 1815 "To Blacksmiths, Eight or Ten good strikers capable of working on large anchors, and other heavy ship work, will find constant employ and liberal wages, by application at the Navy Yard, Washington" [11] Following the War of 1812, the Washington Navy Yard never regained its prominence as a shipbuilding facility. The waters of the Anacostia River were too shallow to accommodate larger battle vessels, and the Yard was deemed too inaccessible to the open sea with a long trip downstream on the Potomac River and South down the Chesapeake Bay to its mouth with the Atlantic Ocean at the Hampton Roads harbor of Virginia. Thus came a shift to what was to be the mission, reason and character of the yard for more than a hundred more years during the 19th century, of: ordnance and technology. During the next decade, the Navy Yard grew to become by 1819 the largest employer in the federal national capital city of Washington, D.C. among all the many departments, bureaus and boards in the District, with a total number of approximately 345 employee / workers.

In 1826, noted writer Anne Royall (1769-1854), toured the Navy Yard. She wrote,[12]

"The navy yard is a complete work-shop, where every naval article is manufactured: it contains twenty-two forges, five furnaces, and a steam-engine. The shops are large and convenient; they are built of brick and covered with copper to secure them from fire. Steel is prepared here with great facility. The numbers of hands employed vary; at present there are about 200. A ship-wright has $2,50 per day, out of which he maintains his wife and family if he have any. Generally wages are very low for all manner of work; a common laborer gets but 75 cents per day, and finds himself. The whole interior of the yard exhibits one continual thundering of hammers, axes, saws, and bellows, sending forth such a variety of sounds and smells, from the profusion of coal burnt in the furnaces, that it requires the strongest nerves to sustain the annoyance."

In 1819, Betsey Howard became the first female worker documented at the navy yard (and perhaps in the federal service), followed shortly after by Ann Spieden. Both Howard and Spieden were employed as horse cart drivers, "and like their male counterparts employed per diem, at $1.54 a day, working whole or part days as required."[13][14] In 1832 the Washington Navy Yard Hospital, hired Eleanor Cassidy O'Donnell to work as a nurse.

During the American Civil War (1861-1865), the Union Navy hired about two dozen women as seamstresses in the Ordnance Department, Laboratory Division. The Department produced naval shells and gunpowder. The women sewed canvas bags that were used to charge ordnance aboard naval vessels. They also sewed signal flags and ensugns for naval vessels. Most of these workers were paid about $1.00 per day.[15] Their work was dangerous, for there was always the risk of a single errant spark igniting nearby gunpowder or pyrotechnics with catastrophic results, such as the tragic huge explosion and fire on 17 June 1864 that killed 21 young women working at the U.S. Army's Washington Arsenal[16][17]

During World War II (1939/1941-1945), the Washington Navy Yard at its peak, employing over 20,000 civilian workers, including 1,400 female ordnance workers.[18]

The Yard was also a leader in industrial technology as it possessed one of the earliest steam engines in the United States. The steam engine was the high-tech marvel of the early District of Columbia life and often commented on by numerous authors and touring visitors. Samuel Batley Ellis, an English immigrant, was the first steam engine operator, and in 1810 was paid the exorbitant sum of a high wage of $2.00 per day. The steam engine ran the sawmill and manufactured anchors, chain, and steam engines for vessels of war.[19] Because of its proximity to the nation's Capitol, the Washington Navy Yard Commandant, was routinely tasked with requests from the Secretary of the Navy and the members of the U.S. Congress. For example on 2 July 1811, the third Navy Secretary Paul Hamilton (politician) (1762-1816, served 1809-1813), in the cabinet and presidential administration of fourth President James Madison (1751-1836, served 1809-1817), ordered Commodore Tingey to provide a "4th of July 18 gun salute, commencing at Sunrise and another commencing at 12 o'clock and yet another commencing at Sunset. Secretary Hamilton then added a note that read: "Rockets are to be displayed on common before the north front of the President's House and could not the USS Wasp be brought West of the bridge or near the bridge, dressed in colors!" [20] The 1835 Washington Navy Yard labor strike was the first labor strike of federal civilian employees.[21] The unsuccessful strike was from 29 July to 15 August 1835. The strike was over working conditions and in support of a ten-hour day.[22][23]

Enslaved Labor

editFor the first thirty years of the 19th century, the Navy Yard was the District's principal employer of enslaved and some free African Americans. Their numbers rose rapidly, and by 1808, the enslaved made up one-third of the workforce.[24] The use of enslaved labor became an in issue in December 1808, when purser Samuel Hanson wrote to Secretary of the Navy Robert Smith alleging that Commodore Thomas Tingey and his deputy John Cassin had both allowed enslaved laborers on the navy yard payroll.Hanson’s charges were serious, namely that Tingey had financially benefited from shipbuilding and lumber contracts. He also accused both Tingey and Cassin of profiting by placing enslaved laborers of their families and friends on shipyard payrolls.[25][26]"In the end, Robert Smith must have felt Hanson’s charges were simply too embarrassing for the Jefferson administration and the Department of the Navy to air in a public inquiry, hence, the case was never brought to court. Hanson’s charges were simply left to fade in the file and no action was taken against Commodore Tingey, John Cassin or Samuel Hanson. Despite official denial, enslaved labor continued at the navy yard and at other locations."[27] The number of enslaved workers gradually declined during the next thirty years. However, free and some enslaved African Americans remained a vital presence. One such person was former slave, later freeman, Michael Shiner 1805-1880 whose diary chronicled his life and work at the navy yard for over half a century [28] There is the documentation for enslaved labor euphemistically called "servants" still working in the blacksmith shop as late as August 1861.[29]

American Civil War era (1861-1865)

edit-

Colored lithograph of Washington Navy Yard, c. 1862

-

The Washington Navy Yard during the American Civil War (1861-1865)

During the American Civil War, the Yard once again became an integral part of the defense of Washington. Commandant Franklin Buchanan (1800-1874), resigned his commission in the United States Navy to join the Confederacy and soon was commissioned an officer in the new infant Confederate States Navy, leaving the Washington Yard to replacement Commander John A. Dahlgren. Newly inaugurated 16th President Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865, served 1861-1865), who held Dahlgren in the highest esteem, was a frequent visitor to the Yard, a few city blocks southeast from the White House. The famous ironclad U.S.S. Monitor was repaired at the Yard after her historic naval clash of the Battle of Hampton Roads harbor with the C.S.S. Virginia. The Lincoln assassination arrested conspirators were quickly brought to the Yard following their capture. The body of assassin John Wilkes Booth was examined and identified on the monitor U.S.S. Montauk, moored at the Yard docks on the Anacostia / Potomac Rivers.

Following the war, the Yard continued to be the scene of technological advances. In 1886, the Yard was designated the manufacturing center for all ordnance in the Navy. Commander Theodore F. Jewell was Superintendent of the Naval Gun Factory from January 1893 to February 1896.

1900s

editOrdnance production continued as the Yard manufactured armament for the Great White Fleet and the World War I navy. The 14-inch (360 mm) naval railway guns used in France during World War I were manufactured at the Yard.

By World War II, the Yard was the largest naval ordnance plant in the world. The weapons designed and built there were used in every war in which the United States fought until the 1960s. At its peak, the Yard consisted of 188 buildings on 126 acres (0.5 km2) of land and employed nearly 25,000 people. Small components for optical systems, parts of Little Boy, and enormous 16-inch (406mm) battleship guns were all manufactured here. In December 1945, the Yard was renamed the U.S. Naval Gun Factory. Ordnance work continued for some years after World War II until finally phased out in 1961. Three years later, on July 1, 1964, the activity was re-designated the Washington Navy Yard. The deserted factory buildings began to be converted to office use.[30] In 1963, ownership of 55 acres of the Washington Navy Yard Annex (western side of Yard including Building 170) was transferred to the General Services Administration.[31] The Yards at the Southeast Federal Center are part of this former property and now includes the headquarters for the United States Department of Transportation.[32]

The Washington Navy Yard was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1973, and designated a National Historic Landmark on May 11, 1976.[30][33] It is part of the Capitol Riverfront Business Improvement District. It is also part of the Navy Yard, also known as Near Southeast, neighborhood. It is served by the Navy Yard – Ballpark Metro station on the Green Line.

2000s

editThe Marine Corps Museum was located on the first floor of the Marine Corps Historical Society in Building 58. The museum closed on July 1, 2005, during the establishment of the National Museum of the Marine Corps near Marine Corps Base Quantico. The Yard was headquarters to the Marine Corps Historical Center. That moved in 2006 to Quantico.

Cultural and scientific

editThe Washington Navy Yard was the scene of many scientific developments. In 1804 at the request of President Thomas Jefferson, navy yard blacksmith Benjamin King built the first White House water closet/toilet. For which Architect Benjamin Latrobe reminded King, " How shall I get the president of the United States into good humor with you about his Water Closet, & his side roof which you were to make? He complains bitterly of you using the privilege of a Man of Genius against him, - that is of being a little forgetful. – I so well know the goodness of your disposition, that I am determined, if possible, to want his quarreling with you at all events about so dirty a business as a Water Closet."[34] King in 1805 again at Jefferson's behest built the first fire engine for the White House°.[35] In December 1807 Robert Fulton approached Robert Smith, Secretary of the Navy and requested that a test of his new torpedo, be authorized at the Washington Navy Yard.[36] Fulton specifically asked that the Navy fabricate copper harpoon torpedoes and provide small boats manned with gunner's mates and boat crews. He envisioned a limited trial on the feasibility of sinking a small sloop. The trial was never funded and a perplexed and exasperated Fulton complained to Jefferson about the naval establishment.[37]

On 4 May 1810 Secretary of the Navy Paul Hamilton (politician), notified Commodore Thomas Tingey, Navy had "conditionally consented" to testing Fulton's Torpedo system and that he was enclosing a copy of Mr. Fulton's "Torpedo War". Hamilton also added "You will prepare and transmit to Mr. Fulton at New York your objections to his system..."[38] In September 1810 the Secretary Hamilton agreed to test Fulton's torpedo, and Commodore Thomas Tingey was directed to transport via stage coach two torpedo harpoon guns from Washington Navy Yard to New York "for Mr. Fulton".[39] To Fulton's chagrin, after a number of attempts the torpedo test ended in failure. In 1822, Commodore John Rodgers built the country's first marine railway for the overhaul of large vessels. John A. Dahlgren developed his distinctive bottle-shaped cannon that became the mainstay of naval ordnance before the Civil War. In 1898, David W. Taylor developed a ship model testing basin, which was used by the Navy and private shipbuilders to test the effect of water on new hull designs. The first shipboard aircraft catapult was tested in the Anacostia River in 1912, and a wind tunnel was completed at the Yard in 1916. The giant gears for the Panama Canal locks were cast at the Yard. Navy Yard technicians applied their efforts to medical designs for prosthetic hands and molds for artificial eyes and teeth.

Navy Yard was Washington's earliest industrial neighborhood. One of the earliest industrial buildings nearby was the eight-story brick Sugar House, built in Square 744 at the foot of New Jersey Avenue, SE, as a sugar refinery in 1797–98. In 1805, it became the Washington Brewery, which produced beer until it closed in 1836. The brewery site was just west of the Washington City Canal in what is now Parking Lot H/I in the block between Nationals Park and the historic DC Water pumping station.[40]

The Washington Navy Yard often functions as a ceremonial gateway to the nation's capital. From early on, due to its proximity to the White House, the navy yard was the site of recurrent presidential visits. The Washington Navy Yard station log confirms many of these visits, for example, those of John Tyler 5 July 1841, James K. Polk 4 March 1845, Franklin Pierce 14 December 1853, and Abraham Lincoln,18 May 1861 and 25 July 1861. There are also entries for foreign delegations and celebrities, e.g., 7 September 1825 for General Lafayette and 15 May 1860 for the visit of the first Japanese Embassy.[41] The body of World War I's Unknown Soldier was received here. Charles A. Lindbergh returned to the Navy Yard in 1927 after his famous transatlantic flight.

During the Civil War, a small number of women worked at the Navy Yard as flag makers and seamstresses, sewing canvas bags for gunpowder.[42] Women again entered the workforce in the 20th century in significant numbers during WWII, where they worked at the Naval Gun Factory making munitions.[42] Following the war, most were discharged. In the modern era, women working at the Yard have increased their presence in executive, managerial, administrative, technical, and clerical positions.

From 1984 to 2015, the decommissioned destroyer USS Barry (DD-933) was a museum ship at the Washington Navy Yard as "Display Ship Barry" (DS Barry). Barry was frequently used for change of command ceremonies for naval commands in the area.[30] Due to declining visitors to the ship, the expensive renovations she required, and the District's plans to build a new bridge that would trap her in the Anacostia River, Barry was towed away during the winter of 2015-2016 for scrapping.[43] The U.S. Navy held an official departure ceremony for the ship on 17 October 2015.[44][45][46]

Today, the Navy Yard houses a variety of activities. It serves as headquarters, Naval District Washington, and houses numerous support activities for the fleet and aviation communities. The Navy Museum welcomes visitors to the Navy Art Collection[47] and its displays of naval art and artifacts, which trace the Navy's history from the Revolutionary War to the present day. The Naval History and Heritage Command is housed in a complex of buildings known as the Dudley Knox Center for Naval History. Leutze Park is the scene of colorful ceremonies.

2013 shooting

editOn September 16, 2013, a shooting took place at the Yard. Shots were fired at the headquarters for the Naval Sea Systems Command Headquarters building #197. Fifteen people, including 13 civilians, one D.C. police officer, and one base officer, were shot. Twelve fatalities were confirmed by the United States Navy and D.C. Police.[48][49] Officials said the gunman, Aaron Alexis, a 34-year-old civilian contractor from Queens, New York, was killed during a gunfight with police.[50]

Operations

editThe Yard serves as a ceremonial and administrative center for the U.S. Navy, home to the Chief of Naval Operations. It is headquarters for the Naval Sea Systems Command, Naval Reactors, Naval Facilities Engineering Command, Naval Historical Center, the Department of Naval History, the U.S. Navy Judge Advocate General's Corps, the United States Navy Band, the U.S. Navy's Military Sealift Command and numerous other naval commands. Several Officers' Quarters are located at the facility.

Building 126

editBuilding 126 is located by the Anacostia River, on the northeast corner of 11th and SE O Streets. The one-story building, built between 1925 and 1938, was recently renovated to be a net-zero energy building as part of the Washington Navy Yard Energy Demonstration Project. Features include two wind turbines, five geothermal wells, a battery energy storage system, one-hundred thirty-two 235 kW solar photovoltaic panels, and windows of electrochromic smart glass.[51]

Although inventoried and determined eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places, it is currently not part of an existing district.[52] Until 1950, Building 126 functioned as the receiving station laundry. Afterward, it served as the site of the Washington Navy Yard Police Station. Currently, it acts as the Visitor Center for the Yard.[53]

Gallery

edit-

View of Washington Navy Yard's dock, circa 1867

-

Experimental Model Basin, circa 1900

-

Torpedo shop at the Washington Navy Yard, circa 1917

-

An aerial view of the destroyer USS Barry (DD-933) docked at the Washington Navy Yard, 15 April 1984

-

Washington Navy Yard Looking West

-

Washington Navy Yard

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites" (PDF). DC.GOV – Office of Planning. State Historic Preservation Office, D.C. Office of Planning. September 30, 2009. p. 171. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 1, 2020. Retrieved May 23, 2023.

- ^ U.S. EPA. "Washington Navy Yard". Superfund Information Systems: Site Progress Profile. Archived from the original on June 16, 2011. Retrieved July 18, 2011.

- ^ Doughty, William Captain, 2nd Regiment (Brent's) District of Columbia Militia War of 1812, NARA RG 94

- ^ "Register of Patients at Naval Hospital, Washington D.C., 1814". NHHC. Retrieved October 26, 2023.

- ^ "About this Collection | James Madison Papers, 1723-1859 | Digital Collections | Library of Congress". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ Mary Stockton Hunter, The Burning of Washington, D.C. New York Historical Society Quarterly Bulletin 1924, pp 80–83.

- ^ Roosevelt, Theodore (1902). The Naval War of 1812, or the History of the United States Navy during the Last War with Great Britain, Part II. New York, NY: G.P. Putnam's Sons. pp. 45–47. Retrieved August 2, 2022.

On August 20th, Major-General Ross and Rear-Admiral Cockburn, with about 5,000 soldiers and marines, moved on Washington by land… Ross took Washington and burned the public buildings; and the panic-struck Americans foolishly burned the Columbia, 44, and Argus, 18, which were nearly ready for service.

- ^ Sharp, John G. History of the Washington Navy Yard Civilian Workforce 1799 -1962 (Naval History and Heritage Command: Washington DC 2005)4., accessed 28 July 2018 https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/browse-by-topic/heritage/washington-navy-yard/pdfs/WNY_History.pdf Archived April 7, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Thomas Tingey to Robert Smith, 12 March 1806, Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy, "Captains Letters" volume 4, letter 47, Roll 0004, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

- ^ "Washington Navy Yard Employee listing dated 23 May 1806 (148 names)". www.genealogytrails.com. Archived from the original on July 20, 2023. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ City of Washington Gazette 15 May 1815, p.3

- ^ Royal, Anne Newport, Sketches of the History, Life and Manner in the United States by a Traveler, (New Haven, by the author, 1826), p.140

- ^ "[UPDATED] Washington Navy Yard Station Log November 1822 - December 1889". NHHC. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ "Washington Navy Yard Payroll for Mechanics and Laborers 1819-1820". genealogytrails.com. Archived from the original on September 15, 2016. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ "Washington Navy Yard 1862 Female Wages Laboratory". genealogytrails.com. Archived from the original on September 15, 2016. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ Daily National Intelligencer, Washington, D.C., June 18, 1864, 3.

- ^ "Fireworks, Hoopskirts—and Death". National Archives. June 30, 2017. Archived from the original on March 22, 2021. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ Sharp, John G. History of the Washington Navy Yard Civilian Workforce 1799 -1962 Naval History and Heritage Command 2005, pp72-76.accessed 5 December 2017 https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/browse-by-topic/heritage/washington-navy-yard/pdfs/WNY_History.pdf Archived April 7, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Papers of Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Maryland Historical Society, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984-1988 Vol.II, pp 908 – 910.

- ^ Paul Hamilton to Tingey, 2 July 1811, Navy Department, Miscellaneous Records of the Navy Department, Records Group 45, Roll 0175, p.33, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

- ^ The Encyclopedia of Strikes in American History editors Aron Brenner, Benjamin Daily and Emanuel Ness, (New York:M.E.Sharpe, 2009),.xvii.

- ^ Maloney, Linda M. The Captain from Connecticut: The Life and Naval Times of Isaac Hull. Northeastern University Press: Boston, 1986 pp 436 - 437

- ^ "washington.html". www.usgwarchives.net. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ "wny2.html". www.usgwarchives.net. Archived from the original on April 7, 2022. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ Sharp John G.M., Washington Navy Yard Purser, Samuel Hanson USN, brings charges against Captain Thomas Tingey and Master Commandant John Cassin 10 Dec 1808 Archived December 5, 2024, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Navy Court Martial Records and Court of Inquiry, 1799-1867, re Thomas Tingey, 10 Dec 1808, Volume 2, Page 21, Case number 55, Case Range, 30-74, Year Range 16 Oct 1805 to 16 Jan 1810, Roll 0004, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

- ^ Sharp,John G.M

- ^ John G. Sharp, Diary of Michael Shiner Relating to the History of the Washington Navy Yard 1813-1869 Archived October 23, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Naval History and Heritage Command 2015 Retrieved Oct. 30, 2016

- ^ Navy-yard, Washington: History from Organization, 1799, to Present Date. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1890.

- ^ a b c "National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form". National Park Service. November 1, 1975. Retrieved July 7, 2009.

- ^ "Request for Determination of Eligibility to the National Register of Historic Places for the Washington Navy Yard Annex". General Services Administration. Historic American Buildings Survey. November 1976. Retrieved July 24, 2009.

- ^ "The Road to Reuse…" (PDF). General Services Administration. Environmental Protection Agency. May 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved March 16, 2016.

- ^ "National Historic Landmarks Survey" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2009.

- ^ "Benjamin Latrobe Letter to Benjamin King about Jefferson's Water Closet". www.genealogytrails.com. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Second Series, Jefferson's Memorandum Books, vol. 2, ed. James A Bear, Jr. and Lucia C. Stanton. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), entry for 8 July 1805, 1143–1171.

- ^ Tingey to Robert Smith, 16 December 1807, Letters from Captains to the Secretary of the Navy ("Captains Letters"), Volume 9, 1 Sept 1807 - 31 Dec 1807, Letter 82, RG 260, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

- ^ "Torpedo War - Rodgers - Fulton". NHHC. Archived from the original on June 4, 2024. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ Hamilton to Tingey, 4 May 1810, Miscellaneous Records of the Navy Department, Letters, 1810, p. 22, Roll 0175, RG45, National Archives and Records Administration

- ^ Paul Hamilton to Tingey, 30 May 1810, Miscellaneous Records of the Navy Department, Record Group 45, Roll, 0175, p.26, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

- ^ Peck, Garrett (2014). Capital Beer: A Heady History of Brewing in Washington, D.C. Charleston, SC: The History Press. ISBN 978-1626194410.

- ^ "[UPDATED] Washington Navy Yard Station Log November 1822 - December 1889". NHHC. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ a b Sharp, John G. (2005). History of the Washington Navy Yard Civilian Workforce, 1799-1962 (PDF). Washington Navy Yard: Naval District Washington. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 7, 2022. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- ^ Copper, Kyle (May 6, 2016). "Museum ship at Navy Yard leaving the nation's capital". WTOP. Archived from the original on June 29, 2017. Retrieved May 6, 2016.

- ^ Dingfelder, Sadie (September 10, 2015). "Bidding farewell to the Barry". Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 29, 2015. Retrieved September 11, 2015.

- ^ Morris, Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Tyrell K. (October 17, 2015). "Navy Bids Farewell to Display Ship Barry". Washington: United States Navy, Chief of Information. Archived from the original on December 3, 2016. Retrieved October 20, 2015.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Eckstein, Megan (October 19, 2015). "Washington Navy Yard Says Goodbye to Display Ship Barry". USNI News.

- ^ Navy Art Collection Archived April 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine web-page. Naval History & Heritage Command official website. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- ^ "Washington Navy Yard shooting: Active shooter sought in Southeast D.C". WJLA TV. Archived from the original on September 16, 2013. Retrieved September 16, 2013.

- ^ "4 killed, 8 injured in a shooting at Washington Navy Yard". Washington Times. Archived from the original on September 16, 2013. Retrieved September 16, 2013.

- ^ DC Navy Yard Gunshots Archived August 14, 2022, at the Wayback Machine; September 16, 2013; CNN.

- ^ Miller, Kiona. "Navy Yard Visitor's Center Completes Net Zero Project". Naval District Washington. Department of the Navy. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved August 6, 2013.

- ^ "11th Street Bridges Final Environmental Impact Statement" (PDF). District of Columbia Department of Transportation. Government of the District of Columbia. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 10, 2014. Retrieved August 6, 2013.

- ^ "Record of Decision for Sites 1, 2, 3, 7, 9, 11, and 13 Washington Navy Yard" (PDF). Naval Facilities Engineering Command Washington. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 10, 2014. Retrieved August 6, 2013.

External links

edit- Washington Navy Yard history Archived October 25, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- "The United States Naval Gun Factory" by Commander Theodore F. Jewell, Harper's Magazine, Vol. 89, Issue 530, July 1894, pp. 251–261.

- Washington Navy Yard Walking Tour C-SPAN3, Thomas Frezza, May 2017

- U.S. Naval Gun Factory Washington, D.C. 1940s U.S. Navy Artillery & Gun Design Movie 26444