National Docks Secondary is a freight rail line within Conrail's North Jersey Shared Assets Area in Hudson County, New Jersey, used by CSX Transportation. It provides access for the national rail network to maritime, industrial, and distribution facilities at Port Jersey, the Military Ocean Terminal at Bayonne (MOTBY), and Constable Hook as well as carfloat operations at Greenville Yard. The line is an important component in the planned expansion of facilities in the Port of New York and New Jersey. The single track right of way comprises rail beds, viaducts, bridges, and tunnels originally developed at the end of the 19th century by competing railroads.

Route

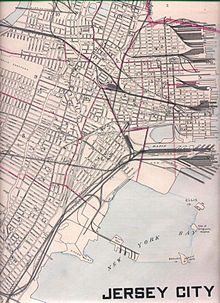

editThe line is used to access the port at the Upper New York Bay, which lies east of those crossing the Northeast Corridor. It runs parallel to the New Jersey Turnpike Newark Bay Extension for most of its length and passes through a cut in the Hudson Palisades. It travels north-south on the east side of Bergen Hill and through a short tunnel crossing beneath the PATH rapid transit system. At its southern end trains cross Newark Bay over the Lehigh Valley Railroad Bridge to the Oak Island Yard in Newark. At is northern end the line travels through Bergen Hill via the Long Dock Tunnel and after passing under Tonnelle Avenue junctions with the Northern Running Track. At North Bergen Yard, the line becomes the River Subdivision.[1] It is an alternate, or secondary, route to the Passaic and Harsimus Line across the Kearny Meadows for trains passing through the Port of New York and New Jersey.

Renewal and expansion of port

editThe National Docks Secondary is an integral component in the anticipated expansion of the Liberty Corridor [2][3][4] and Cross Harbor Freight Movement projects, including the intermodal container transhipment operations on the west side of the Upper New York Bay in the Port of New York and New Jersey. To that end, as of 2010, the track is being restored, tunnel clearances increased, and redundant overhead bridges removed to allow double stacking of the high-cube containers increasingly favored for intermodal transportation.[3][5][6][7] The line will connect with ExpressRail Port Jersey, a ship-to-rail container transfer operation, planned to open in 2014,[8] and to the planned new post-Panamax container terminal at MOTBY.[9] As of June 2018, the crossing Chapel Avenue was updated and expanded at and siding tracks added between Linden Avenue and Liberty State Park.

History

editThe line is a remnant of the extensive freight rail infrastructure that once dominated much of the Hudson County, its right of way a combination of routes originally developed by different companies. The name is taken from the National Docks Railway which maintained yards and a storage depot at Black Tom, an island in the Upper New York Bay that was greatly expanded by land reclamation and connected to the north of Caven Point by a long causeway.[10][11] The line was built during an era of tremendous growth along the west shores of the bay and the North River (Hudson River), fueled by competing railroads wishing to gain access to the harbor to develop shipping and carfloat operations as well as intermodal passenger transport terminals.[12][13]

Standard Oil era

editThe complex history of the line reflects the shifting alliances between competing railroads in the region. The National Storage Company was an arm of Standard Oil, which constructed storage and lighterage facilities on Black Tom Island and the Communipaw shoreline in 1876.[14] Standard Oil had a contract with the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) for transporting oil, but the railroad's charter prevented it from extending a line from its cut through Bergen Hill to the National Storage facility. The National Storage Company was thus compelled to use the Central Railroad of New Jersey, which had tracks adjacent to the Black Tom facility.[15]

To circumvent the restrictions on the Pennsylvania Railroad's charter, Standard Oil and the Pennsylvania colluded in 1879 to create the National Docks Railway Company, connecting the National Storage facilities directly to the Pennsylvania line. The line would of necessity run through the property of the Central Railroad of New Jersey, and the Central strongly objected to the condemnation of its land for the benefit of its competitor.[15] After an extended legal battle, the National Docks won a surprise concession in 1882 from the Jersey City aldermen to build an elevated track between the junction with the PRR and the oil docks,[16] and the line was quickly constructed and opened in 1883, operated by the Pennsylvania Railroad. The line was subsequently extended as the Bergen Neck Railroad to Constable Hook in Bayonne where Standard Oil had additional facilities.[14] In 1891, the Bergen Neck Railroad and the National Docks Railway were consolidated.[17]

Six years after its initial construction, Standard Oil reached an agreement in 1889 with the New York Central Railroad (NYC) to connect the National Docks Railway with the NYC's West Shore Railroad at National Junction.[1] The line consisted of the New Jersey Junction Railroad and the National Docks and New-Jersey Junction Connecting Railroad, with the National Docks Railway coming under the control of the NYC. It was now the Pennsylvania's turn to protest against the crossing of its property, and a costly "frog war" ensued.[12] When it was finally completed in 1897, the 450-foot (140 m) long tunnel under Pennsylvania's Waldo Avenue yards had cost $750,000, twice what had been projected.[18][19]

Lehigh Valley era

editThe Lehigh Valley Railroad (LVRR) initially reached its terminal on the Morris Canal Basin over the Central Railroad's line and later obtained trackage rights on the National Docks Railway. To protect access to its terminal, the LVRR acquired a half-interest in the National Docks in 1890.[20] In 1891, the LVRR consolidated its other holdings in northeastern New Jersey to form the Lehigh Valley Terminal Railway,[17] and it began running a route on a bridge over Newark Bay in 1892.[21][22]

In 1897, another consolidation took place with the merger of the National Docks Railway Company, New Jersey Junction Connecting Railway Company, the Kill von Kull Railway, and Bay Creek Railway, the latter two being short lines running south to Bayonne. The merged company was known as the National Docks Railway. Much of the company was eventually absorbed by the Lehigh Valley Railroad in 1898.[1] By 1900, the LVRR had full ownership of the line to its terminal at the mouth of the Hudson.[23] Under the direction of the LVRR, the National Docks Railway remained an important connecting line along the Hudson Waterfront, handling traffic for the Erie, New York Central, and Pennsylvania.[1]

In 1911, the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad, the forerunner of the Port Authority Trans Hudson, opened a tunnel under the PRR right of way from its Exchange Place terminal.[24] It emerges in the yard and passes over what is now known as the Waldo Tunnel. The New Jersey Junction Railroad later became part of Conrail's River Line until it was abandoned, and the right of way in Hoboken and Weehawken is now used by Hudson Bergen Light Rail.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d Heiss, Ralph (August 24, 2009). The Lehigh Valley Railroad Across New Jersey. Arcadia Publishing. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-7385-6576-7.

- ^ "Cross Harbor". Crossharborfreight.net. Archived from the original on 2012-03-16. Retrieved 2012-03-18.

- ^ a b "Liberty Corridor National Docks Rail" (Press release). New Jersey Transit. May 2008. Archived from the original on 2011-12-19. Retrieved 2010-11-21.

- ^ Tirella, Tricia (Oct 17, 2010). "24 million in railway improvement celebrated north Hudson driver see more 'efficient' trains, fewer train crossing delays". Hudson Reporter. Archived from the original on 2011-07-12. Retrieved 2011-02-27.

- ^ "Northern New Jersey" (PDF). How Tomorrow Moves. CSX. October 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-07-15. Retrieved 2010-11-19.

- ^ Consolidated Rail Corporation (May 11, 2009). "Freight Service". Archived from the original on July 22, 2012.

- ^ Richard Grubb and Associates. "Conrail Bergen Tunnel/Waldo Tunnel Improvements" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-15. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ^ Strunsky, Steve (October 21, 2010). "Port Authority begins development of ship-to-rail container facility in Jersey City". Star-Ledger. Newark. Archived from the original on November 26, 2010. Retrieved November 21, 2010.

- ^ Sullivan, Al (Aug 4, 2010). "Will open a port, not new housing BLRA sells waterfront property to Port Authority for $235M". Hudson Reporter. Archived from the original on 2012-02-27. Retrieved 2010-11-20.

- ^ "The Point Of Rocks Line More about the Little Railroad" (PDF). New York Times. September 8, 1879. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-09-22. Retrieved 2010-11-20.

- ^ Carmela Karnoutsos (2009). "Black Tom Explosion". New Jersey City University. Archived from the original on December 5, 2010. Retrieved July 5, 2009.

- ^ a b "Great Railroads At War Fighting to Secure Lands on Jersey Shore" (PDF). New York Times. December 15, 1889. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-06-18. Retrieved 2010-11-16.

- ^ "WEEHAWKEN IMPROVEMENTS; Filling up of the Cove--New Railroads--A City of Termini over the River" (PDF). The New York Times. June 4, 1869. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 30, 2022. Retrieved June 13, 2018.

- ^ a b Joint Report with Comprehensive Plan and Recommendations. New York, New Jersey Port and Harbor Development Commission. Dec 16, 1920. p. 116.

national docks lehigh valley.

- ^ a b "The Point Of Rocks Line An Important Railroad Suit" (PDF). New York Times. August 13, 1879. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-11-30. Retrieved 2010-11-22.

- ^ "Stultified Legislators. The Jersey City Aldermen Vote Away Many Valuable Grants" (PDF). New York Times. April 4, 1889. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-11-30. Retrieved 2010-11-22.

- ^ a b "News About Railroads Consolidation of Several New Jersey Roads" (PDF). New York Times. August 27, 1891. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-11-30. Retrieved 2010-11-22.

- ^ "A Small Costly Tunnel" (PDF). New York Times. July 5, 1896. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-08-19. Retrieved 2010-11-22.

- ^ "The Short Line of the New Jersey Junction Company Practically Completed A Bitter Struggle Ended" (PDF). New York Times. March 11, 1897. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-11-30. Retrieved 2010-11-20.

- ^ Lehigh Valley Railroad Company (1885). Annual Report of the Lehigh Valley Railroad Company for the Fiscal Year Ending November 30th, 1890. p. 15.

- ^ "Lehigh Valley in Jersey" (PDF). New York Times. January 15, 1891. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-11-30. Retrieved 2010-11-16.

- ^ Lehigh Valley Railroad Company (1885). Annual Report of the Lehigh Valley Railroad Company for the Fiscal Year Ending November 30th, 1892. p. 9.

- ^ "Lehigh Valley Merger Railway System's Subsidiary Lines Consolidated" (PDF). New York Times. July 30, 1900. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-11-30. Retrieved 2010-11-20.

- ^ "Improve Transit Facilities by Newark High Spreed Line" (PDF). New York Times. October 11, 1911. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-02-08. Retrieved 2010-11-22.

External links

editMedia related to National Docks Secondary at Wikimedia Commons

- YouTube:Cabride on National Docks Secondary from Long Dock Tunnel to Liberty State Park

- Blue Comet website photo: Conrail seen passing JCMC

- National Aemerican Engineering Record

- RRpicarchiives

- Cross Harbor Freight Movement Project

- HAER