Nashville is a city in Howard County, Arkansas, United States. The population was 4,627 at the 2010 census.[4] The estimated population in 2018 was 4,425.[5] The city is the county seat of Howard County.[6]

Nashville, Arkansas | |

|---|---|

|

Clockwise from top: Nashville Commercial Historic District, Howard County Courthouse, Flavius Holt House, Scrapper Stadium at Nashville High School, Howard County Museum, Nashville City Hall | |

| Motto: "Sharing the Hometown Feeling"[1] | |

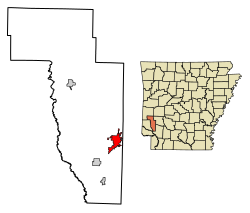

Location of Nashville in Howard County, Arkansas. | |

| Coordinates: 33°56′54″N 93°50′49″W / 33.94826°N 93.84704°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Arkansas |

| County | Howard |

| Area | |

• Total | 5.52 sq mi (14.29 km2) |

| • Land | 5.47 sq mi (14.17 km2) |

| • Water | 0.04 sq mi (0.12 km2) |

| Elevation | 400 ft (100 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 4,153 |

| • Density | 759.09/sq mi (293.11/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 71852 |

| Area code | 870 |

| FIPS code | 05-48560 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2404349[3] |

| Website | www |

Nashville is situated at the base of the Ouachita foothills and was once a major center of the peach trade in southwest Arkansas. Today the land is mostly given over to cattle and chicken farming. The world's largest dinosaur trackway was discovered near the town in 1983.

History

editMine Creek Baptist Church was built along the banks of Mine Creek by the Rev. Isaac Cooper Perkins (1790–1852) in the area where Nashville now stands around 1835.[7] Settlers later established a post stop along the settlement roads in 1840,[8]: 902–903 and a post office incorporated in 1848.[7] Michael Womack (1794–1861), a Tennessee native reputed to have killed the British general Edward Pakenham during the War of 1812, settled in the area with his family in 1849.[9] The area was then known by locals as "Mine Creek", but was also called "Hell's Valley"[10] and "Pleasant Valley".

Settlement in the area progressed slowly but steadily, though industry declined during the Civil War. Following the war, the village's prospects improved, industry and settlement picked up, and the town was officially incorporated as Nashville on October 18, 1883, with D.A. Hutchinson serving as the first mayor.[8]: 903 Womack is attributed with first proposing the name and called the town after Nashville, Tennessee.[9] The following year, Nashville and Hope were connected via railroad, spurring further growth, and the county seat was relocated from Center Point to Nashville.[11] With the establishment of county government in the town, and due to the increased trade and access brought by the railroad, Nashville continued to grow. The town had a population of 928 in 1900, and boasted "a cotton-compress and gin" and a "bottling-works";[12] by 1920 the population had risen to 2,144.[8]: 903

In the years before the Great Depression, Nashville was a prosperous, if small, town. According to author Dallas T. Herndon, Nashville was "a banking town, with electric lights, waterworks, an ice and cold storage plant, a canning factory, foundries, machine shops, a flour mill, two newspapers, a brick factory, fruit box and crate factory, mercantile concerns... well-kept streets, [and] modern public schools."[8]: 903

An EF2 tornado struck the town on May 10, 2015, and killed two people.

Geography

editNashville is located in southeastern Howard County. U.S. Routes 278 and 371 run concurrently through the northern side of the city. US 371 leads east 34 miles (55 km) to Prescott and west 19 miles (31 km) to Lockesburg. US 278 leads northwest 19 miles (31 km) to Dierks and southeast 28 miles (45 km) to Hope. Arkansas Highway 27 joins US 278 in a bypass around the eastern side of Nashville; SR 27 leads northeast 13 miles (21 km) to Murfreesboro and southwest 8 miles (13 km) to Mineral Springs.

According to the United States Census Bureau, Nashville has a total area of 5.7 square miles (14.7 km2), of which 0.04 square miles (0.1 km2), or 0.76%, are water.[4] The city is in the valley of Mine Creek, a south-flowing tributary of the Saline and Little rivers.

Climate

editThe climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild to cool winters. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Nashville has a humid subtropical climate, abbreviated "Cfa" on climate maps.[13]

| Climate data for Nashville, Arkansas (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1899–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 84 (29) |

85 (29) |

90 (32) |

92 (33) |

97 (36) |

107 (42) |

107 (42) |

113 (45) |

110 (43) |

101 (38) |

87 (31) |

81 (27) |

113 (45) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 54.0 (12.2) |

58.5 (14.7) |

66.5 (19.2) |

74.7 (23.7) |

81.7 (27.6) |

89.3 (31.8) |

93.4 (34.1) |

93.9 (34.4) |

87.9 (31.1) |

77.2 (25.1) |

65.1 (18.4) |

56.4 (13.6) |

74.9 (23.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 42.9 (6.1) |

46.7 (8.2) |

54.3 (12.4) |

62.1 (16.7) |

70.8 (21.6) |

78.6 (25.9) |

82.4 (28.0) |

82.1 (27.8) |

75.7 (24.3) |

64.3 (17.9) |

53.1 (11.7) |

45.3 (7.4) |

63.2 (17.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 31.7 (−0.2) |

35.0 (1.7) |

42.1 (5.6) |

49.5 (9.7) |

59.8 (15.4) |

68.0 (20.0) |

71.4 (21.9) |

70.3 (21.3) |

63.5 (17.5) |

51.4 (10.8) |

41.0 (5.0) |

34.3 (1.3) |

51.5 (10.8) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −12 (−24) |

−14 (−26) |

8 (−13) |

23 (−5) |

36 (2) |

46 (8) |

54 (12) |

51 (11) |

30 (−1) |

24 (−4) |

12 (−11) |

−5 (−21) |

−14 (−26) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.95 (100) |

4.24 (108) |

5.05 (128) |

5.74 (146) |

6.15 (156) |

4.24 (108) |

4.10 (104) |

3.18 (81) |

3.74 (95) |

5.02 (128) |

4.44 (113) |

5.12 (130) |

54.97 (1,396) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 1.2 (3.0) |

1.0 (2.5) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.3 (0.76) |

2.6 (6.6) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.1 | 10.3 | 10.9 | 9.5 | 10.3 | 8.2 | 7.5 | 6.9 | 6.3 | 7.8 | 9.0 | 9.9 | 106.7 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 1.2 |

| Source: NOAA[14][15] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 172 | — | |

| 1890 | 810 | 370.9% | |

| 1900 | 928 | 14.6% | |

| 1910 | 2,374 | 155.8% | |

| 1920 | 2,144 | −9.7% | |

| 1930 | 2,469 | 15.2% | |

| 1940 | 2,782 | 12.7% | |

| 1950 | 3,548 | 27.5% | |

| 1960 | 3,579 | 0.9% | |

| 1970 | 4,016 | 12.2% | |

| 1980 | 4,554 | 13.4% | |

| 1990 | 4,639 | 1.9% | |

| 2000 | 4,878 | 5.2% | |

| 2010 | 4,627 | −5.1% | |

| 2020 | 4,153 | −10.2% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[16] | |||

2020 census

edit| Race | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 1,726 | 41.56% |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 1,391 | 33.49% |

| Native American | 8 | 0.19% |

| Asian | 49 | 1.18% |

| Pacific Islander | 3 | 0.07% |

| Other/Mixed | 179 | 4.31% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 797 | 9.19% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 4,153 people, 1,733 households, and 1,085 families residing in the city.

2000 census

editAs of the census[18] of 2000, there were 4,878 people, 1,857 households, and 1,179 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,067.7 inhabitants per square mile (412.2/km2). There were 2,136 housing units at an average density of 467.5 per square mile (180.5/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 59.96% White, 30.21% Black or African American, 5.25% Native American, 1.23% Asian, 0.02% Pacific Islander, 4.39% from other races, and 0.94% from two or more races. 6.99% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 1,857 households, out of which 33.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 41.6% were married couples living together, 18.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 36.5% were non-families. 32.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 14.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.45 and the average family size was 3.12.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 27.6% under the age of 18, 9.6% from 18 to 24, 27.0% from 25 to 44, 19.2% from 45 to 64, and 16.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35 years. For every 100 females, there were 89.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 83.4 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $23,480, and the median income for a family was $28,611. Males had a median income of $24,494 versus $17,480 for females. The per capita income for the city was $13,258. About 18.7% of families and 21.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 29.4% of those under age 18 and 16.3% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

editPeach farming

editPeach farming sustained Nashville during the Depression. The peach industry came to the Nashville area in the late nineteenth century. Peak years of production lasted from the 1920s until the 1950s. Nashville's peak peach production was 1950, with over 400,000 bushels collected from 425 orchards. "Up to 175 boxcars, each carrying 396 bushel baskets, were shipped from Nashville each day during peak production years."[19] Late freezes and early thaws in 1952 and 1953 led to the devastation of the peach harvests. Two-thirds of the crops were destroyed, and production sank to 150,000 bushels. "The Arkansas growers lost the market, and the impact was devastating. For Howard County growers, the only option was to pull up the trees and convert the land for other purposes, often pasture for cattle, or to raise chickens," which remain the dominant agricultural products in the Nashville area to this day.[19]

The peach industry in the area continued to decline as industrial farming in the Sun Belt and shifting production patterns made southwest Arkansas less attractive to larger produce companies. However, many small peach orchards still remain and are farmed by local families.

Arts and culture

editMuseums and other points of interest

editThe National Register of Historic Places lists several entries of significant historical value from Nashville.[20] Among them:

- The First Christian Church building, built in the Late Gothic Revival style in the early 20th century, is still an active church.

- The Howard County Museum is located in the First Presbyterian Church building, built in the Eastlake style in the early 1900s.

- Garrett Whiteside Hall is all that remains of the Nashville High School complex built in the 1930s. It is used for storage and special activities by the local school district.

- Elbert W. Holt House, and Flavius Holt House, Colonial Revival structures, are still used as private residences.

- Howard County Courthouse is one of the few public buildings in Arkansas built in the Moderne or Art Deco style.

Dinosaur discoveries

editThe largest find of dinosaur trackways in the world was discovered by SMU archaeology graduate student Brad Pittman in a quarry north of the town in 1983, the site of a prehistoric beach.[21][22][23] A field of 5–10,000 sauropod footprints were found in a mudstone layer covering a layer of gypsum.[24] Casts 65 feet (20 m) long and 7 feet (2.1 m) wide were made and put on permanent display, first at the courthouse and finally at the Nashville City Park, while many of the original tracks were disbursed to local museums such as the Mid-America Museum in Hot Springs and the Arkansas Museum of Discovery in Little Rock. The full extent of the trackway has never been excavated.

Education

editColleges and universities

editNashville hosts a campus of the Cossatot Community College of the University of Arkansas. The school operates out of a facility constructed in 2006 on 35 acres (140,000 m2) of land west of town. The college has programs in business administration, nursing, truck driving, welding, residential construction, cosmetology, and general education coursework. The college also provides non-credit coursework in adult education such as GED classes, ESL training, test preparation, and computer literacy.

High schools

editNashville High School is a public secondary school for students in grades 10 through 12, and is accredited by both the Arkansas State Board of Education and the North Central Association.[25] The high school is administered by the Nashville Public School District. In the 2006–07 school year, Nashville High School had 43 teachers and a student enrollment of 390, with a student/teacher ratio of 9:1.[26] In 2010, the Nashville Junior High School Quiz Bowl team won the National Championship in Quiz Bowl. The event was held in New Orleans, Louisiana. The High School Quiz Bowl team won the State 4A Championship in 2012. In addition to academic coursework, Nashville High School has active chapters in FCCLA, FFA, and the National Honor Society. Nashville High School has participated in the EAST Initiative since 2001.

The Nashville Scrappers compete in interscholastic sports under the sanction of the Arkansas Activities Association in sports such as football, basketball, baseball, cheerleading, cross country running, golf, softball, track and field, tennis, and trap shooting. Nashville High School sports teams compete at the class 4A level. Nashville High School celebrated its 100th year in high school football in 2009.

Civic and religious organizations

editNashville has active chapters of national and international fraternal service organizations, including Lions Clubs International and Rotary International. In the 1960s and again in the 1980s–90s, Nashville supported several Boy Scouts of America troops as well.

2009 marked the 160th anniversary of the Pleasant Valley Masonic Lodge in Nashville. There has been an uninterrupted Masonic presence in Nashville since this time. The original lodge was founded with 165 members, and was named before the township changed its name to Nashville.[27]

The Elberta Arts & Humanities Council is located in Nashville, hosted by the Elberta Arts Center. The center is a permanent collection of art from local artists and hosts ongoing exhibits of local work and items of regional interest, such as the original 1950s electronic marquee from the Art Deco, 1,500-seat Elberta Theater (1943–1996).

Nashville is home to a variety of religious groups, representing congregations among the Assemblies of God, Baptists, Methodists, the Jehovah's Witnesses, the Roman Catholic Church, the Churches of Christ, Christian Churches, the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church, as well as non-denominational, charismatic, and Pentecostal congregations.

Infrastructure

editRailroads

editThe first railroad to connect Nashville with the surrounding area was originally known as the Washington & Hope Railroad Co., chartered in 1876.[28] The first stage of the railroad was a 10-mile (16 km) stretch connecting Hope and Washington, Arkansas, in 1879. In 1881 the railroad was renamed the Arkansas and Louisiana Railway Co., and on October 1, 1884, a nearly 26-mile (42 km) extension to Nashville was opened.[28] By the start of the 20th century the railroad was operated as an extension of the St. Louis, Iron Mountain and Southern Railway, which stretched from St. Louis, Missouri to Texarkana, Arkansas.[28] The earliest trains coming in and out of Nashville operated under the Missouri Pacific Railroad mark.

At one time the city boasted three railroads:

- The earliest was the Iron Mountain Railway branch from Nashville to Hope.

- The second, granted a charter on June 22, 1906, was the Memphis Paris and Gulf (MP&G), later the Memphis Dallas and Gulf.[29] The track ran twenty-five miles from Nashville to Ashdown, Arkansas, and then on to Hot Springs, Arkansas. The MP&G was broken up in 1922 forming the Graysonia Nashville and Ashdown (GN&A) running 32 miles (51 km) from Nashville to Ashdown. The GN&A was merged into the Kansas City Southern Railroad in 1993.[30]

- The third railroad in Nashville was the Murfreesboro Nashville Southwestern (MNSW), which ran from Nashville to Murfreesboro, Arkansas, in 1909. The MNSW later became the Murfreesboro-Nashville railroad which folded in 1951.[31]

Notable people

edit- Trevor Bardette, film actor

- Effie Anderson Smith, impressionist landscape painter

- Boyd A. Tackett, Arkansas politician

- Thomas Philip Watson, Oklahoma state senator, born in Nashville

Companies

editWilliam T. Dillard, founder of Dillard's, opened his first department store in Nashville.[32] He started his successful franchise in 1938 when, with $8,000 borrowed from his father, he opened a small store in his wife's hometown of Nashville. Aside from a short period during World War II, the Dillard Company continued operating and expanding its Nashville location. In 1948, Dillard, looking for more growth prospects, sold the Nashville store and used the money, along with some outside financing, to buy controlling interest in a store in nearby Texarkana.[33]

Jim Yates, founder of one of the largest privately owned convenience store chains, built his first E-Z Mart store in Nashville, Arkansas.[34]

References

edit- ^ "City of Nashville Arkansas Chamber of Commerce". City of Nashville Arkansas Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Nashville, Arkansas

- ^ a b "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Nashville city, Arkansas". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved April 21, 2017.[dead link]

- ^ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved October 1, 2019.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ a b The Nashville Leader, 21 Sept. 2009

- ^ a b c d Dallas T. Herndon (1922). Centennial History of Arkansas, Volume 1. Chicago and Little Rock: S.J. Clarke. ISBN 9780893080686.

- ^ a b "Michael Womack – Pioneer Arkansan". Retrieved December 26, 2015.

- ^ Arkansas Historical Quarterly. "Hell's Valley, Nashville", 13:265

- ^ "ArkansasHeritage.com". Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved August 7, 2008.

- ^ Lippencott's New Gazetteer: A Complete Pronouncing Gazetteer or Geographical Dictionary of the World, Vol.2. A. Heilprin and L. Heilprin, Eds. (Philadelphia: J. Lippencott, 1906):1257

- ^ "Nashville, Arkansas Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Retrieved December 26, 2015.

- ^ "NOWData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved November 2, 2023.

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991-2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved November 2, 2023.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ a b "Peach Industry – Encyclopedia of Arkansas". Retrieved December 26, 2015.

- ^ "National Register of Historical Places – ARKANSAS (AR), Howard County". Retrieved December 26, 2015.

- ^ "Nashville's Sauropod Trackway". Archived from the original on July 4, 2007. Retrieved July 2, 2007.

- ^ Pittman, Jeffrey G. and David D. Gillett, "Tracking the Arkansas Dinosaurs," The Arkansas Naturalist (March 1984) v. 2 no. 3, pp 1–12.

- ^ Pittman, Jeffrey, Transactions of the Gulf Coast Association of Geological Societies, vol. XXXIV (1984), pp. 202–209

- ^ "Geologists to Make Casts of Rare Dinosaur Prints," Arkansas Gazette, January 1, 1984; sec. B, p. 8, col. 5.

- ^ NCA CASI Arkansas[permanent dead link], Retrieved September 18, 2009

- ^ National Center for Education Statistics, CCD Public school data 2006–2007 school year, Retrieved September 18, 2009

- ^ Pleasant Valley Lodge #30[permanent dead link], Retrieved September 10, 2009

- ^ a b c Annual report of the Railroad Commission of the State of Arkansas, Volume 3 (Hot Springs: Sentinel Record, 1903):354

- ^ Arkansas Biennial Report of the Secretary of State, 1905–1906. (Little Rock: Tunnah & Pittard, 1906):376

- ^ American Shortline Railway Guide, 5th Ed. Edward A. Lewis (Waukasha, WI: Kalmbach, 1996):357

- ^ "Murfreesboro (Pike County) – Encyclopedia of Arkansas". Retrieved December 26, 2015.

- ^ "William T. Dillard, Founder of a Retail Chain, Dies at 87". The New York Times. February 9, 2002. Retrieved December 26, 2015.

- ^ "Dillards – - Dillard's, Inc. – History of Dillard's, Inc". Archived from the original on December 20, 2015. Retrieved December 26, 2015.

- ^ "E-Z Mart". Archived from the original on January 29, 2011. Retrieved January 6, 2011.