The Nabataean Kingdom (Nabataean Aramaic: 𐢕𐢃𐢋𐢈 Nabāṭū), also named Nabatea (/ˌnæbəˈtiːə/) was a political state of the Nabataeans during classical antiquity. The Nabataean Kingdom controlled many of the trade routes of the region, amassing large wealth and drawing the envy of its neighbors. It stretched south along the Tihamah into the Hejaz, up as far north as Damascus, which it controlled for a short period (85–71 BC). Nabataea remained an independent political entity from the mid-3rd century BC until it was annexed in AD 106 by the Roman Empire, which it renamed Arabia Petraea.

Nabataean Kingdom 𐢕𐢃𐢋𐢈 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3rd century BC–106 AD | |||||||||||||

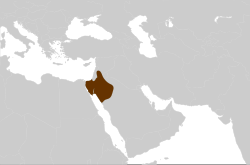

The Nabataean Kingdom at its greatest extent | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Petra 30°19′43″N 35°26′31″E / 30.3286°N 35.4419°E | ||||||||||||

| Common languages |

| ||||||||||||

| Religion | Nabataean religion | ||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Nabataean | ||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||

| Historical era | Antiquity | ||||||||||||

• Established | 3rd century BC | ||||||||||||

| 90 BC | |||||||||||||

• Conquered by the Roman Empire | 106 AD | ||||||||||||

| Currency | Nabataean Denarius | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

History

editNabataeans

editThe Nabataeans were one among several nomadic Bedouin Arab tribes that roamed the Arabian Desert and moved with their herds to wherever they could find pasture and water.[1] They became familiar with their area as seasons passed, and they struggled to survive during bad years when seasonal rainfall diminished.[1] The origin of the specific tribe of Arab nomads remains uncertain. One hypothesis locates their original homeland in today's Yemen, in the southwest of the Arabian Peninsula, but their deities, language and script share nothing with those of southern Arabia.[1] Another hypothesis argues that they came from the eastern coast of the peninsula.[1]

The suggestion that they came from the Hejaz area is considered to be more convincing, as they share many deities with the ancient people there; nbṭw, the root consonant of the tribe's name, is found in the early Semitic languages of Hejaz.[1] Similarities between late Nabataean Arabic dialect and the ones found in Mesopotamia during the Neo-Assyrian period, as well as a group with the name of "Nabatu" being listed by the Assyrians as one of several rebellious Arab tribes in the region, suggests a connection between the two.[1] The Nabataeans might have originated from there and migrated west between the 6th and 4th centuries BC into northwestern Arabia and much of what is now modern-day Jordan.

Nabataeans have been falsely associated with other groups of people. A people called the "Nabaiti", who were defeated by the Assyrian King Ashurbanipal, were associated by some with the Nabataeans because of the temptation to link their similar names. Another misconception is their identification with the Nebaioth of the Hebrew Bible, the descendants of Ishmael, Abraham's son.[1]

Emergence

editThe literate Nabataeans left no lengthy historical texts. However, thousands of inscriptions have been found in their settlements, including graffiti and on minted coins.[2] The Nabataeans appear in historical records from the 4th century BC,[3] although there seems to be evidence of their existence before that time. Aramaic ostraca finds indicate that the Achaemenid province Idumaea must have been established before 363 BC, after the failed revolt of Hakor of Egypt and Evagoras I of Salamis against the Persians.[3] The Qedarites joined the failed revolt and consequently lost significant territory and their privileged position in the frankincense trade, and they were presumably replaced by the Nabataeans.[3] It has been argued that the Persians lost interest in the former territory of the Edomite Kingdom after 400 BC, allowing the Nabataeans to gain prominence in that area.[3] All of these changes would have allowed Nabataeans to control the frankincense trade from Dedan to Gaza.[3]

The first historical reference to the Nabataeans is by Greek historian Diodorus Siculus who lived around 30 BC. Diodorus refers accounts made 300 years earlier by Hieronymus of Cardia, one of Alexander the Great's generals, who had a first-hand encounter with the Nabataeans. Diodorus relates how the Nabataeans survived in a waterless desert and managed to defeat their enemies by hiding in the desert until the latter surrendered for lack of water. The Nabataeans dug cisterns that were covered and marked by signs known only to themselves.[4] Diodorus wrote about how they were "exceptionally fond of freedom" and includes an account about unsuccessful raids that were initiated by Greek general Antigonus I in 312 BC.[1]

neither the Assyrians of old, nor the kings of the Medes and Persians, nor yet those of the Macedonians have been able to enslave them, and... they never brought their attempts to a successful conclusion. - Diodorus.[1]

After Alexander the Great's death in 323 BC, his empire split among his generals. During the conflict between Alexander's generals, Antigonus conquered the Levant, and this brought him to the borders of Edom, just north of Petra.[5] According to Diodorus, Antigonus sought to add "the land of the Arabs who are called Nabataeans" to his existing territories of Syria and Phoenicia.[6] The Nabataeans were distinguished from the other Arab tribes by wealth.[7] The Nabataeans generated revenues from the trade caravans that transported frankincense, myrrh and other spices from Eudaemon in today's Yemen, across the Arabian Peninsula, passing through Petra and ending up in the Port of Gaza for shipment to European markets.[8]

Antigonus ordered one of his officers, Athenaeus, to raid the Nabataeans with 4,000 infantry and 600 cavalry, and loot herds and processions. Athenaeus learned that every year the Nabataeans gathered for a festival during which women, children, and elders were left at "a certain rock" (later interpreted by some as the future city of "Petra", "rock" in Greek.)[9] Athenaeus attacked "the rock" in 312 BC while the Nabataeans were away trading; the inhabitants were taken by surprise, and tonnes of spices and silver were looted. Athenaeus departed before nightfall and made camp to rest 200 stadion away, where they thought they would be safe from Nabataean counter-attack. The camp was attacked by 8,000 pursuing Nabataean soldiers and—as Diodorus describes it—"all the 4,000 foot-soldiers were slain, but of the 600 horsemen about 50 escaped, and of these the larger part were wounded";[9][10] Athenaeus was killed.[9][11] The army had deployed no scouts, a failure that Diodorus ascribes to Athenaeus's failure to anticipate the rapidity of the Nabataean response. After the Nabataeans returned to their rock, they wrote a letter to Antigonus accusing Athenaeus and declaring that they had destroyed his army in self-defence.[9][10] Antigonus replied by blaming Athenaeus for acting unilaterally, intending to lull the Nabataeans into a false sense of security.[9][12] But the Nabataeans, though pleased with Antigonus' response, remained suspicious and established outposts on the edge of the mountains in preparation for future attacks.[9][13][12]

Antigonus' second attack was with an army of 4,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry led by Antigonus' son Demetrius "the Besieger".[9][14] The Nabataean scouts spotted the marching enemy and used smoke signals to warn of the approaching army.[9][15] The Nabataeans dispersed their herds and possessions to guarded locations in harsh terrain—such as deserts and mountain tops—which would be difficult for the Demetrius to attack, and garrisoned "the rock" to defend what remained.[9][15] Demetrius attacked "the rock" through its "single artificial approach", but the Nabataeans managed to repulse the invading force.[9][15] A Nabataean called out to Demetrius pointing out that his aggression made no sense, for the land was semi-barren and the Nabataeans had no desire to be their slaves.[9][12] Realizing his limited supplies and the determination of the Nabataean fighters, Demetrius accepted peace and withdrew with hostages and gifts.[9][15][12] Demetrius drew Antigonus' displeasure for the peace, but this was ameliorated by Demetrius' reports of bitumen deposits in the Dead Sea,[9] a valuable commodity.[15][16]

Antigonus sent an expedition, this time under Hieronymus of Cardia, to extract bitumen from the Dead Sea.[9] A force of 6,000 Arabs sailing on reed rafts approached Hieronymus's troops and killed them with arrows.[9] These Arabs were almost certainly Nabataeans.[16] Antigonus thus lost all hope of generating revenue in that manner.[9] The event is described as the first conflict caused by a Middle Eastern petroleum product.[17] The series of wars among the Greek generals ended in a dispute over the lands of modern-day Jordan between the Ptolemies based in Egypt and the Seleucids based in Syria. The conflict enabled the Nabataeans to extend their kingdom beyond Edom.[18]

Diodorus mentions that the Nabataeans had attacked merchant ships belonging to the Ptolemies in Egypt at an unspecified date, but were soon targeted by a larger force and "punished as they deserved".[19] While it is unknown why the wealthy Nabataeans turned to piracy, one possible reason is that they felt that their trade interests were threatened by the gradual understanding of the nature of monsoon in the Red Sea from the 3rd century BC onward[19] (see Periplus of the Erythraean Sea).

Political state

editThe Nabataean Arabs did not emerge as a political power suddenly; their rise instead went through two phases.[20] The first phase was in the 4th century BC (ruled then by an elders' council),[21] which was marked by the growth of Nabataean control over trade routes and various tribes and towns. Their presence in Transjordan by the end of the 4th century BC is guaranteed by Antigonus' operations in the region, and despite recent suggestions that there is no evidence of Nabataean occupation of the Hauran in the early period, the Zenon papyri firmly attest the penetration of the Hauran by the Nabataeans in the mid-3rd century BC, and according to Bowersock it "establish[es] these Arabs in one of the principal areas of subsequent splendor".[22] Simultaneously, the Nabataeans had probably moved across the 'Araba to the west into the desert tracts of the Negev.[23] In their early history, before establishing urban centers the Nabataeans demonstrated on several occasions their impressive and well organized military prowess by successfully defending their territory against larger powers.[24]

The second phase saw the creation of the Nabataean political state in the mid-3rd century BC.[20] Kingship is regarded as a characteristic of a state and urban society.[25] The Nabataean institution of kingship came about as a result of multiple factors, such as the indispensabilities of trade organization and war;[26] the subsequent outcomes of the Greek expeditions on the Nabataeans played a role in the political centralization of the Nabatu tribe. The earliest evidence of Nabataean kingship comes from a Nabataean inscription in the Hauran region, probably Bosra,[27] which mentions a Nabataean king whose name was lost, dated by Stracky to the early 3rd century BC.[28] The dating is significant, since the available evidence does not attest the existence of Nabataean monarchy until the 2nd century BC.[28] This nameless Nabataean king perhaps could be linked with a reference from the Zenon archive (the second historical mention of the Nabataeans)[19][note 1] to deliveries of grain to "Rabbel's men", Rabbel being a characteristically royal Nabataean name,[29] it is thus possible to link Rabbel of the Zenon archive with the nameless king of Bosra's inscription, though it is highly speculative.[30]

A recent papyrological discovery, the Milan Papyrus, provides further evidence. The relevant part of the Lithika section of the papyrus describes an Arabian cavalry of a certain Nabataean king,[31] providing an early 3rd century BC reference to a Nabataean monarch.[26] The word Nabataean stands alone beside a missing word that start with the letter M; one of the suggested words for filling the gap is the traditional name of Nabataean kings, Malichus.[32] Furthermore, the anonymous Nabataean coins dated by Barkay to the second half of the 3rd century BC, found mainly in Nabataean territory, support such an early date of the Nabataean Kingdom. This is in line with Strabo's account (whose description of Arabia derives ultimately from reports by 3rd century BC Ptolemaic officials) that the Nabataean kingship was old and traditional.[33] Rachel Barkay concludes "the Nabataean economy and political regime were in existence by the 3rd century BC".[32] The kingship of the Nabataeans was, in the view of Strabo, an effective one, where the Nabataean kingdom was "very well governed" and the king was "a man of the people".[34] For more than four centuries the Nabataean kingdom dominated, politically and commercially, a large territory and was arguably the first Arab kingdom in the area.[35]

The testimony of the 4th and 3rd century external accounts and local materialistic evidence demonstrate that the Nabataeans played a relatively substantial political and economic role in the sphere of the early Hellenistic world.[26] While the Nabataeans did not attain observable characteristics of a Hellenistic state (i.e. monumental architecture) in their early period, similar to contemporary Seleucid Syria, the Milan papyrus speaks of their wealth and prestige in this period. In that respect, the Nabataeans must be considered a unique entity.[26]

Aretas I, mentioned in the Second Book of Maccabees as "the tyrant of the Arabs" (169-168 BC), is regarded as the first explicitly named king of the Nabataeans. In 2 Maccabees, the high-priest Jason, driven by his rival Menelaus, seeks the protection of Aretas.[36] Upon his arrival at the land of the Nabataeans, Aretas imprisons Jason.[37] It is not clear why or when that happened; his arrest by Aretas was either after he escaped Jerusalem where Aretas, fearing the retaliation of Antiochus IV Epiphanes for "openly demonstrating pro-Ptolemaic stand" (in Hammond's view however, Aretas hoped to use Jason as a political bargaining counter with the Seleucids), arrested Jason.[37] Or his imprisonment might have happened at a later date (167 BC) as a result of the established friendship between the Nabataeans and Judas Maccabaeus, aimed to hand Jason to the Jews. "Either suggestion is feasible and so the riddle remains unresolved", according to Kasher.[37]

A Nabataean inscription in the Negev mentions a Nabataean king called Aretas; the date given by Starcky is not later than 150 BC.[38] However, the dating is difficult. It has been claimed that the inscription dates to the 3rd century BC, based on the pre-Nabataean writing style,[39] or somewhere in the 2nd century BC.[40] Generally, the inscription is attributed to Aretas I or perhaps to Aretas II.[41]

Around the same time, the Arab Nabataeans and the neighboring Jewish Maccabees had maintained a friendly relationship; the former had sympathized with the Maccabees who were being mistreated by the Seleucids.[30] Romano-Jewish historian Josephus reports that Judas Maccabeus and his brother Jonathan marched three days into the wilderness before encountering the Nabataeans in the Hauran, where they were settled in for at least a century.[42] The Nabataeans treated them peacefully and told them of what happened to the Jews residing in the land of Galaad. This peaceful meeting between the Nabataeans and two brothers in the First Book of Maccabees seems to contradict a parallel account from the second book where a pastoral Arab tribe launches a surprise attack on the two brothers.[42] Despite open contradiction between the two accounts, scholars tend to identify the plundering Arab tribe of the second book with the Nabataeans in the first book.[42] They were evidently not Nabataeans, for good relations between the Maccabees and their "friends", the Nabataeans, continued to exist.[30] The friendly relations between them is further emphasized by Jonathan's decision to send his brother John to "lodge his baggage" with the Nabataeans until the battle with the Seleucids is over.[30] Again, the Maccabean caravan suffers an attack by a murderer Arab tribe in the vicinity of Madaba.[43] This tribe was clearly not Nabataean, for they are identified as the sons of Amrai.[43] In Bowersock's view, the interpretation of the evidence in the Books of Maccabees "illustrates the danger of assuming that any reference to Arabs in areas known to have been settled by the Nabataeans must automatically refer to them".[43] But the picture is different, many Arab tribes in the region continued to be nomadic and moved in and out of the emerging Nabataean kingdom, and the Nabataeans, as well as invading armies and eventually the Romans also, had to cope with these people.[43]

The Nabataeans began to mint coins during the 2nd century BC, revealing the extensive economic and political independence they enjoyed.[2] Petra was included in a list of major cities in the Mediterranean area to be visited by a notable from Priene, a sign of the significance of Nabataea in the ancient world. Petra was counted with Alexandria, which was considered to be a supreme city in the civilized world.[2]

Relationship with Hasmoneans

editThe Nabataeans were allies of the Maccabees during their struggles against the Seleucid monarchs. They then became rivals of their successors, the Judaean Hasmonean dynasty, and a chief element in the disorders which invited Pompey's intervention in Judea.[44] Gaza City was the last stop for spices that were carried by trade caravans before shipment to European markets, giving the Nabataeans considerable influence over the Gazans.[2] Hasmonean King Alexander Jannaeus besieged and occupied Gaza in 96 BC, murdering many of its inhabitants.[2] Jannaeus then captured several territories in Transjordan north of Nabataea, along the road to Damascus, including northern Moab and Gilead. These territorial acquisitions threatened Nabataean trade interests in Gaza and in Damascus.[45] Nabataean King Obodas I regained control of these areas after his forces defeated Jannaeus in the Battle of Gadara around 93 BC.[2]

After the Nabataean victory over the Judaeans, the Nabataeans were at odds with the Seleucids, who were concerned about the increasing influence of the Nabataeans to the south of their territories.[46] During the Battle of Cana, the Seleucid king Antiochus XII waged war against the Nabataeans. Antiochus was slain during combat, and his army fled and perished in the desert from starvation. After Obodas's victories over the Judaeans and the Seleucids, he was worshipped as a god by his people. He was buried in the Temple of Oboda in Avdat, where inscriptions have been found referring to "Obodas the god".[2]

The kingdom seems to have reached its territorial zenith during the reign of Aretas III (87 to 62 BC). In 62 BC, a Roman army under the command of Marcus Aemilius Scaurus besieged Petra. The defeated Aretas paid tribute to Scaurus and recognized Roman supremacy over Nabataea.[47] The Nabataean Kingdom was slowly surrounded by the expanding Roman Empire, which conquered Egypt and annexed Hasmonean Judea. While the Nabataean kingdom managed to preserve its formal independence, it became a client kingdom under the influence of Rome.[47]

Roman annexation

editIn 106 AD, during the reign of Roman emperor Trajan, the last king of the Nabataean kingdom Rabbel II Soter died,[47] which may have prompted the official annexation of Nabatea to the Roman Empire.[47] Some epigraphic evidence suggests a military campaign, commanded by Cornelius Palma, the governor of Syria. Roman forces seem to have come from Syria and also from Egypt. It is clear that by 107 Roman legions were stationed in the area around Petra and Bosra, as is shown by a papyrus found in Egypt.

The kingdom was annexed by the empire to become the province of Arabia Petraea. Trade seems to have largely continued thanks to the Nabataeans' undiminished talent for trading.[47] Under Hadrian, the limes Arabicus ignored most of the Nabatæan territory and ran northeast from Aila (modern Aqaba) at the head of the Gulf of Aqaba. A century later, during the reign of Alexander Severus, the local issue of coinage came to an end. There was no more building of sumptuous tombs, apparently because of a sudden change in political ways, such as an invasion by the neo-Persian power under the Sassanid Empire. The city of Palmyra, for a time the capital of the breakaway Palmyrene Empire, grew in importance and attracted the Arabian trade away from Petra.[48][49]

Geography

editThe Nabataean Kingdom was situated between the Arabian and Sinai Peninsulas. Its northern neighbour was the Hasmonean kingdom, and its south western neighbour was Ptolemaic Egypt. Its capital was Raqmu (Petra), and it included the towns of Bosra, Hegra (Mada'in Saleh), and Nitzana/Nessana.

Raqmu was a wealthy trading town, located at a convergence of several important trade routes. One of them was the Incense Route which was based around the production of both myrrh and frankincense in southern Arabia,[48] and ran through Mada'in Saleh to Petra. From there, aromatics were distributed throughout the Mediterranean region.

See also

editReferences

editNotes

edit- ^ The Zenon archive mentions Dionysius, one of two Greek employees who sought an alternative career of selling women as sex slaves, he was once detained by the Nabataeans for a week during one of his expeditions.[19] Considering what is known of the Nabataean society's remarkable gender equality at later time, it is likely that they were objecting to the treatment of women in their area, for whom they believed they were responsible in the course of maintaining law and order.[19]

Citations

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i Taylor 2001, p. 14.

- ^ a b c d e f g Jane, Taylor (2001). Petra and the Lost Kingdom of the Nabataeans. London, United Kingdom: I.B.Tauris. pp. 14, 17, 30, 31. ISBN 9781860645082. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Wenning 2007, p. 26.

- ^ Taylor 2001, p. 17.

- ^ Taylor 2001, p. 30.

- ^ Bowersock 1994, p. 13.

- ^ Mills, Bullard & McKnight 1990, p. 598.

- ^ Taylor 2001, p. 8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Diodorus Siculus, Book XIX, 95-100, Loeb Classical Library edition, 1954, accessed 27 December 2019

- ^ a b Taylor 2001, p. 31.

- ^ Groot 1879, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d Bowersock 1994, p. 14.

- ^ Healey 2001, p. 28.

- ^ McLaughlin 2014, p. 51.

- ^ a b c d e McLaughlin 2014, p. 52.

- ^ a b Hammond 1973, p. 68.

- ^ Waterfield 2012, p. 123.

- ^ Salibi 1998, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d e Taylor 2001, p. 38.

- ^ a b Al-Abduljabbar 1995, p. 8.

- ^ Al-Abduljabbar 1995, p. 136.

- ^ Bowersock 1994, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Bowersock 1994, p. 18.

- ^ Bowes 1998, p. 4.

- ^ Bowes 1998, p. 106.

- ^ a b c d Pearson 2011, p. 10.

- ^ Milik 2003, p. 275.

- ^ a b Al-Abduljabbar 1995, p. 147.

- ^ Bowersock 1994, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d Taylor 2001, p. 40.

- ^ Levy, Daviau & Younker 2016, p. 335.

- ^ a b Barkay 2015, p. 433.

- ^ Barkay 2011, p. 69.

- ^ Sullivan 1990, p. 72.

- ^ Al-Abduljabbar 1995, p. 1.

- ^ Starcky 1955, p. 84.

- ^ a b c Kasher 1988, p. 24.

- ^ Kropp 2013, p. 41.

- ^ Sartre 2005, p. 17.

- ^ Taylor 2001, p. 219.

- ^ Pearson 2011, p. 13.

- ^ a b c Bowersock 1994, p. 19.

- ^ a b c d Bowersock 1994, p. 20.

- ^ Johnson, Paul (1987). A History of the Jews. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-79091-4.

- ^ Josephus, Flavius (1981). The Jewish War. Vol. 1. Trans. G. A. Williamson 1959. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Penguin. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-14-044420-9.

- ^ Ball, Warwick (10 June 2016). Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire. Routledge. p. 65. ISBN 9781317296355. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Taylor, Jane; Petra; p.25-31; Aurum Press Ltd; London; 2005; ISBN 9957-451-04-9

- ^ a b Teller, Matthew; Jordan; p.265; Rough Guides; Sept 2009; ISBN 978-1-84836-066-2

- ^ Greenfield, Jonas Carl (2001). 'Al Kanfei Yonah. BRILL. ISBN 9004121706. Retrieved 27 August 2014.

Sources

edit- Al-Abduljabbar, Abdullah (1995). The rise of the Nabataeans: sociopolitical developments in 4th and 3rd century BC Nabataea (PhD). Indiana University.

- Barkay, Rachel (2015). "NEW ASPECTS OF NABATAEAN COINS". ARAM. 27: 431–439.

- Barkay, Rachel (2011). "The Earliest Nabataean Coinage". The Numismatic Chronicle. 171: 67–73. JSTOR 42667225.

- Bowersock, Glen (1994). Roman Arabia. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-77756-9.

- Bowes, Alan R. (1998). The Process of Nabataean Sedentarization: New Models and Approaches. Department of Anthropology, University of Utah.

- Groot, N. G. De (1879). The History of the Israelites and Judæans: Philosophical and Critical. Trübner & Company.

- Hammond, Philip C. (1959). "The Nabataean Bitumen Industry at the Dead Sea". The Biblical Archaeologist. 22 (2): 40–48. doi:10.2307/3209307. ISSN 0006-0895. JSTOR 3209307. S2CID 133997328.

- Hammond, Philip C. (1973). The Nabataeans -- their history, culture and archaeology. P. Åström (S. vägen 61). ISBN 978-91-85058-57-0.

- Healey, John F. (2001). The Religion of the Nabataeans: A Conspectus. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-10754-1.

- Kasher, Aryeh (1988). Jews, Idumaeans, and Ancient Arabs: Relations of the Jews in Eretz-Israel with the Nations of the Frontier and the Desert During the Hellenistic and Roman Era (332 BCE-70 CE). Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3-16-145240-6.

- Kropp, Andreas J. M. (27 June 2013). Images and Monuments of Near Eastern Dynasts, 100 BC - AD 100. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-967072-7.

- Levy, Thomas Evan; Daviau, P.M. Michele; Younker, Randall W. (16 June 2016). Crossing Jordan: North American Contributions to the Archaeology of Jordan. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-47856-2.

- McLaughlin, Raoul (11 September 2014). The Roman Empire and the Indian Ocean: The Ancient World Economy and the Kingdoms of Africa, Arabia and India. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-78346-381-7.

- Milik, J.T. (2003), "Appendice, inscription nabatéenne archaïque. Une bilingue arameo-grecque de 105/104 avant J.-C.", in J. Dentzer-Feydy; J.-M. Dentzer; P.-M. Blanc (eds.), Hauran II: Les Installations de Sī 8 du Sanctuaire à l'Etablissement Viticole I (in French), Beirut

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Mills, Watson E.; Bullard, Roger Aubrey; McKnight, Edgar V. (1990). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Mercer University Press. ISBN 978-0-86554-373-7.

- Pearson, Jeffrey Eli (2011). Contextualizing the Nabataeans: A Critical Reassessment of Their History and Material Culture (PhD). University of California, Berkeley.

- Salibi, Kamal S. (15 December 1998). The Modern History of Jordan. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-331-6.

- Sartre, Maurice (2005). The Middle East Under Rome. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01683-5.

- Starcky, Jean (1955). "The Nabataeans: A Historical Sketch". The Biblical Archaeologist. 18 (4): 84–106. doi:10.2307/3209134. ISSN 0006-0895. JSTOR 3209134. S2CID 134256604.

- Sullivan, Richard (1990). Near Eastern royalty and Rome, 100-30 BC. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-2682-8.

- Taylor, Jane (2001). Petra and the Lost Kingdom of the Nabataeans. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-508-2.

- Waterfield, Robin (11 October 2012). Dividing the Spoils: The War for Alexander the Great's Empire. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-993152-1.

- Wenning, Robert (2007). "The Nabataeans in History (Before AD 106).". In Konstantinos D. Politis (ed.). The World of the Nabataeans. Vol. 2 of the International Conference, The World of the Herods and the Nabataeans, Held at the British Museum, 17–19 April 2001. Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 978-3-515-08816-9.

Further reading

edit- Benjamin, Jesse. "Of Nubians and Nabateans: Implications of research on neglected dimensions of ancient world history." Journal of Asian and African Studies 36, no. 4 (2001): 361–82.

- Fittschen, Klaus, and G Foerster. Judaea and the Greco-Roman World In the Time of Herod In the Light of Archaeological Evidence: Acts of a Symposium. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1996.

- Kropp, Andreas J. M. "Nabatean Petra: the royal palace and the Herod connection." Boreas 32 (2009): 43–59.

- Negev, Avraham. Nabatean Archaeology Today. New York: New York University Press, 1986.

- del Rio Sánchez, Francisco, and Juan Pedro Monferrer Sala. Nabatu: The Nabataeans through their Inscriptions. Barcelona: University of Barcelona, 2005.

External links

edit- A map of the VIA NOVA TRAIANA showing the outposts that made up Hadrian's limes