In evolutionary biology, robustness of a biological system (also called biological or genetic robustness[1]) is the persistence of a certain characteristic or trait in a system under perturbations or conditions of uncertainty.[2][3] Robustness in development is known as canalization.[4][5] According to the kind of perturbation involved, robustness can be classified as mutational, environmental, recombinational, or behavioral robustness etc.[6][7][8] Robustness is achieved through the combination of many genetic and molecular mechanisms and can evolve by either direct or indirect selection. Several model systems have been developed to experimentally study robustness and its evolutionary consequences.

Classification

editMutational robustness

editMutational robustness (also called mutation tolerance) describes the extent to which an organism's phenotype remains constant in spite of mutation.[9] Robustness can be empirically measured for several genomes[10][11] and individual genes[12] by inducing mutations and measuring what proportion of mutants retain the same phenotype, function or fitness. More generally robustness corresponds to the neutral band in the distribution of fitness effects of mutation (i.e. the frequencies of different fitnesses of mutants). Proteins so far investigated have shown a tolerance to mutations of roughly 66% (i.e. two thirds of mutations are neutral).[13]

Conversely, measured mutational robustnesses of organisms vary widely. For example, >95% of point mutations in C. elegans have no detectable effect[14] and even 90% of single gene knockouts in E. coli are non-lethal.[15] Viruses, however, only tolerate 20-40% of mutations and hence are much more sensitive to mutation.[10]

Robustness to stochasticity

editBiological processes at the molecular scale are inherently stochastic.[16] They emerge from a combination of stochastic events that happen given the physico-chemical properties of molecules. For instance, gene expression is intrinsically noisy. This means that two cells in exactly identical regulatory states will exhibit different mRNA contents.[17][18] The cell population level log-normal distribution of mRNA content[19] follows directly from the application of the Central Limit Theorem to the multi-step nature of gene expression regulation.[20]

Environmental robustness

editIn varying environments, perfect adaptation to one condition may come at the expense of adaptation to another. Consequently, the total selection pressure on an organism is the average selection across all environments weighted by the percentage time spent in that environment. Variable environment can therefore select for environmental robustness where organisms can function across a wide range of conditions with little change in phenotype or fitness (biology). Some organisms show adaptations to tolerate large changes in temperature, water availability, salinity or food availability. Plants, in particular, are unable to move when the environment changes and so show a range of mechanisms for achieving environmental robustness. Similarly, this can be seen in proteins as tolerance to a wide range of solvents, ion concentrations or temperatures.

Genetic, molecular and cellular causes

editGenomes mutate by environmental damage and imperfect replication, yet they display remarkable tolerance. This comes from robustness both at many different levels.

Organism mutational robustness

editThere are many mechanisms that provide genome robustness. For example, genetic redundancy reduces the effect of mutations in any one copy of a multi-copy gene.[21] Additionally the flux through a metabolic pathway is typically limited by only a few of the steps, meaning that changes in function of many of the enzymes have little effect on fitness.[22][23] Similarly metabolic networks have multiple alternate pathways to produce many key metabolites.[24]

Protein mutational robustness

editProtein mutation tolerance is the product of two main features: the structure of the genetic code and protein structural robustness.[25][26] Proteins are resistant to mutations because many sequences can fold into highly similar structural folds.[27] A protein adopts a limited ensemble of native conformations because those conformers have lower energy than unfolded and mis-folded states (ΔΔG of folding).[28][29] This is achieved by a distributed, internal network of cooperative interactions (hydrophobic, polar and covalent).[30] Protein structural robustness results from few single mutations being sufficiently disruptive to compromise function. Proteins have also evolved to avoid aggregation[31] as partially folded proteins can combine to form large, repeating, insoluble protein fibrils and masses.[32] There is evidence that proteins show negative design features to reduce the exposure of aggregation-prone beta-sheet motifs in their structures.[33] Additionally, there is some evidence that the genetic code itself may be optimised such that most point mutations lead to similar amino acids (conservative).[34][35] Together these factors create a distribution of fitness effects of mutations that contains a high proportion of neutral and nearly-neutral mutations.[12]

Gene expression robustness

editDuring embryonic development, gene expression must be tightly controlled in time and space in order to give rise to fully functional organs. Developing organisms must therefore deal with the random perturbations resulting from gene expression stochasticity.[36] In bilaterians, robustness of gene expression can be achieved via enhancer redundancy. This happens when the expression of a gene under the control of several enhancers encoding the same regulatory logic (ie. displaying binding sites for the same set of transcription factors). In Drosophila melanogaster such redundant enhancers are often called shadow enhancers.[37]

Furthermore, in developmental contexts were timing of gene expression in important for the phenotypic outcome, diverse mechanisms exist to ensure proper gene expression in a timely manner.[36] Poised promoters are transcriptionally inactive promoters that display RNA polymerase II binding, ready for rapid induction.[38] In addition, because not all transcription factors can bind their target site in compacted heterochromatin, pioneer transcription factors (such as Zld or FoxA) are required to open chromatin and allow the binding of other transcription factors that can rapidly induce gene expression. Open inactive enhancers are call poised enhancers.[39]

Cell competition is a phenomenon first described in Drosophila[40] where mosaic Minute mutant cells (affecting ribosomal proteins) in a wild-type background would be eliminated. This phenomenon also happens in the early mouse embryo where cells expressing high levels of Myc actively kill their neighbors displaying low levels of Myc expression. This results in homogeneously high levels of Myc.[41][42]

Developmental patterning robustness

editPatterning mechanisms such as those described by the French flag model can be perturbed at many levels (production and stochasticity of the diffusion of the morphogen, production of the receptor, stochastic of the signaling cascade, etc). Patterning is therefore inherently noisy. Robustness against this noise and genetic perturbation is therefore necessary to ensure proper that cells measure accurately positional information. Studies of the zebrafish neural tube and antero-posterior patternings has shown that noisy signaling leads to imperfect cell differentiation that is later corrected by transdifferentiation, migration or cell death of the misplaced cells.[43][44][45]

Additionally, the structure (or topology) of signaling pathways has been demonstrated to play an important role in robustness to genetic perturbations.[46] Self-enhanced degradation has long been an example of robustness in System biology.[47] Similarly, robustness of dorsoventral patterning in many species emerges from the balanced shuttling-degradation mechanisms involved in BMP signaling.[48][49][50]

Evolutionary consequences

editSince organisms are constantly exposed to genetic and non-genetic perturbations, robustness is important to ensure the stability of phenotypes. Also, under mutation-selection balance, mutational robustness can allow cryptic genetic variation to accumulate in a population. While phenotypically neutral in a stable environment, these genetic differences can be revealed as trait differences in an environment-dependent manner (see evolutionary capacitance), thereby allowing for the expression of a greater number of heritable phenotypes in populations exposed to a variable environment.[51]

Being robust may even be a favoured at the expense of total fitness as an evolutionarily stable strategy (also called survival of the flattest).[52] A high but narrow peak of a fitness landscape confers high fitness but low robustness as most mutations lead to massive loss of fitness. High mutation rates may favour population of lower, but broader fitness peaks. More critical biological systems may also have greater selection for robustness as reductions in function are more damaging to fitness.[53] Mutational robustness is thought to be one driver for theoretical viral quasispecies formation.

Emergent mutational robustness

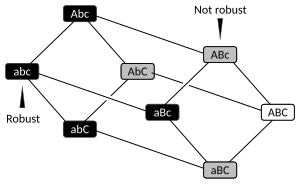

editNatural selection can select directly or indirectly for robustness. When mutation rates are high and population sizes are large, populations are predicted to move to more densely connected regions of neutral network as less robust variants have fewer surviving mutant descendants.[54] The conditions under which selection could act to directly increase mutational robustness in this way are restrictive, and therefore such selection is thought to be limited to only a few viruses[55] and microbes[56] having large population sizes and high mutation rates. Such emergent robustness has been observed in experimental evolution of cytochrome P450s[57] and B-lactamase.[58] Conversely, mutational robustness may evolve as a byproduct of natural selection for robustness to environmental perturbations.[59][60][61][62][63]

Robustness and evolvability

editMutational robustness has been thought to have a negative impact on evolvability because it reduces the mutational accessibility of distinct heritable phenotypes for a single genotype and reduces selective differences within a genetically diverse population.[citation needed] Counter-intuitively however, it has been hypothesized that phenotypic robustness towards mutations may actually increase the pace of heritable phenotypic adaptation when viewed over longer periods of time.[64][65][66][67]

One hypothesis for how robustness promotes evolvability in asexual populations is that connected networks of fitness-neutral genotypes result in mutational robustness which, while reducing accessibility of new heritable phenotypes over short timescales, over longer time periods, neutral mutation and genetic drift cause the population to spread out over a larger neutral network in genotype space.[68] This genetic diversity gives the population mutational access to a greater number of distinct heritable phenotypes that can be reached from different points of the neutral network.[64][65][67][69][70][71][72] However, this mechanism may be limited to phenotypes dependent on a single genetic locus; for polygenic traits, genetic diversity in asexual populations does not significantly increase evolvability.[73]

In the case of proteins, robustness promotes evolvability in the form of an excess free energy of folding.[74] Since most mutations reduce stability, an excess folding free energy allows toleration of mutations that are beneficial to activity but would otherwise destabilise the protein.

In sexual populations, robustness leads to the accumulation of cryptic genetic variation with high evolutionary potential.[75][76]

Evolvability may be high when robustness is reversible, with evolutionary capacitance allowing a switch between high robustness in most circumstances and low robustness at times of stress.[77]

Methods and model systems

editThere are many systems that have been used to study robustness. In silico models have been used to model promoters,[78][79] RNA secondary structure, protein lattice models, or gene networks. Experimental systems for individual genes include enzyme activity of cytochrome P450,[57] B-lactamase,[58] RNA polymerase,[13] and LacI[13] have all been used. Whole organism robustness has been investigated in RNA virus fitness,[10] bacterial chemotaxis, Drosophila fitness,[15] segment polarity network, neurogenic network and bone morphogenetic protein gradient, C. elegans fitness[14] and vulval development, and mammalian circadian clock.[9]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Kitano, Hiroaki (2004). "Biological robustness". Nature Reviews Genetics. 5 (11): 826–37. doi:10.1038/nrg1471. PMID 15520792. S2CID 7644586.

- ^ Stelling, Jörg; Sauer, Uwe; Szallasi, Zoltan; Doyle, Francis J.; Doyle, John (2004). "Robustness of Cellular Functions". Cell. 118 (6): 675–85. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.008. PMID 15369668. S2CID 14214978.

- ^ Félix, M-A; Wagner, A (2006). "Robustness and evolution: Concepts, insights and challenges from a developmental model system" (PDF). Heredity. 100 (2): 132–40. doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6800915. PMID 17167519.

- ^ Waddington, C. H. (1942). "Canalization of Development and the Inheritance of Acquired Characters". Nature. 150 (3811): 563–5. Bibcode:1942Natur.150..563W. doi:10.1038/150563a0. S2CID 4127926.

- ^ De Visser, JA; Hermisson, J; Wagner, GP; Ancel Meyers, L; Bagheri-Chaichian, H; Blanchard, JL; Chao, L; Cheverud, JM; et al. (2003). "Perspective: Evolution and detection of genetic robustness". Evolution; International Journal of Organic Evolution. 57 (9): 1959–72. doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb00377.x. JSTOR 3448871. PMID 14575319. S2CID 221736785.

- ^ Fernandez-Leon, Jose A. (2011). "Evolving cognitive-behavioural dependencies in situated agents for behavioural robustness". Biosystems. 106 (2–3): 94–110. doi:10.1016/j.biosystems.2011.07.003. PMID 21840371.

- ^ Fernandez-Leon, Jose A. (2011). "Behavioural robustness: A link between distributed mechanisms and coupled transient dynamics". Biosystems. 105 (1): 49–61. doi:10.1016/j.biosystems.2011.03.006. PMID 21466836.

- ^ Fernandez-Leon, Jose A. (2011). "Evolving experience-dependent robust behaviour in embodied agents". Biosystems. 103 (1): 45–56. doi:10.1016/j.biosystems.2010.09.010. PMID 20932875.

- ^ a b Wagner A (2005). Robustness and evolvability in living systems. Princeton Studies in Complexity. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-12240-7.[page needed]

- ^ a b c Sanjuán, R (Jun 27, 2010). "Mutational fitness effects in RNA and single-stranded DNA viruses: common patterns revealed by site-directed mutagenesis studies". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 365 (1548): 1975–82. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0063. PMC 2880115. PMID 20478892.

- ^ Eyre-Walker, A; Keightley, PD (Aug 2007). "The distribution of fitness effects of new mutations". Nature Reviews Genetics. 8 (8): 610–8. doi:10.1038/nrg2146. PMID 17637733. S2CID 10868777.

- ^ a b Hietpas, RT; Jensen, JD; Bolon, DN (May 10, 2011). "Experimental illumination of a fitness landscape". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (19): 7896–901. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.7896H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1016024108. PMC 3093508. PMID 21464309.

- ^ a b c Guo, HH; Choe, J; Loeb, LA (Jun 22, 2004). "Protein tolerance to random amino acid change". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101 (25): 9205–10. Bibcode:2004PNAS..101.9205G. doi:10.1073/pnas.0403255101. PMC 438954. PMID 15197260.

- ^ a b Davies, E. K.; Peters, A. D.; Keightley, P. D. (10 September 1999). "High Frequency of Cryptic Deleterious Mutations in Caenorhabditis elegans". Science. 285 (5434): 1748–1751. doi:10.1126/science.285.5434.1748. PMID 10481013.

- ^ a b Baba, T; Ara, T; Hasegawa, M; Takai, Y; Okumura, Y; Baba, M; Datsenko, KA; Tomita, M; Wanner, BL; Mori, H (2006). "Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection". Molecular Systems Biology. 2 (1): 2006.0008. doi:10.1038/msb4100050. PMC 1681482. PMID 16738554.

- ^ Bressloff, Paul C. (2014-08-22). Stochastic processes in cell biology. Cham. ISBN 978-3-319-08488-6. OCLC 889941610.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Elowitz, M. B. (2002-08-16). "Stochastic Gene Expression in a Single Cell" (PDF). Science. 297 (5584): 1183–1186. Bibcode:2002Sci...297.1183E. doi:10.1126/science.1070919. PMID 12183631. S2CID 10845628.

- ^ Blake, William J.; KÆrn, Mads; Cantor, Charles R.; Collins, J. J. (April 2003). "Noise in eukaryotic gene expression". Nature. 422 (6932): 633–637. Bibcode:2003Natur.422..633B. doi:10.1038/nature01546. PMID 12687005. S2CID 4347106.

- ^ Bengtsson, M.; Ståhlberg, A; Rorsman, P; Kubista, M (16 September 2005). "Gene expression profiling in single cells from the pancreatic islets of Langerhans reveals lognormal distribution of mRNA levels". Genome Research. 15 (10): 1388–1392. doi:10.1101/gr.3820805. PMC 1240081. PMID 16204192.

- ^ Beal, Jacob (1 June 2017). "Biochemical complexity drives log-normal variation in genetic expression". Engineering Biology. 1 (1): 55–60. doi:10.1049/enb.2017.0004. S2CID 31138796.

- ^ Gu, Z; Steinmetz, LM; Gu, X; Scharfe, C; Davis, RW; Li, WH (Jan 2, 2003). "Role of duplicate genes in genetic robustness against null mutations". Nature. 421 (6918): 63–6. Bibcode:2003Natur.421...63G. doi:10.1038/nature01198. PMID 12511954. S2CID 4348693.

- ^ Kauffman, Kenneth J; Prakash, Purusharth; Edwards, Jeremy S (October 2003). "Advances in flux balance analysis". Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 14 (5): 491–496. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2003.08.001. PMID 14580578.

- ^ Nam, H; Lewis, NE; Lerman, JA; Lee, DH; Chang, RL; Kim, D; Palsson, BO (Aug 31, 2012). "Network context and selection in the evolution to enzyme specificity". Science. 337 (6098): 1101–4. Bibcode:2012Sci...337.1101N. doi:10.1126/science.1216861. PMC 3536066. PMID 22936779.

- ^ Krakauer, DC; Plotkin, JB (Feb 5, 2002). "Redundancy, antiredundancy, and the robustness of genomes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (3): 1405–9. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.1405K. doi:10.1073/pnas.032668599. PMC 122203. PMID 11818563.

- ^ Taverna, DM; Goldstein, RA (Jan 18, 2002). "Why are proteins so robust to site mutations?". Journal of Molecular Biology. 315 (3): 479–84. doi:10.1006/jmbi.2001.5226. PMID 11786027.

- ^ Tokuriki, N; Tawfik, DS (Oct 2009). "Stability effects of mutations and protein evolvability". Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 19 (5): 596–604. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2009.08.003. PMID 19765975.

- ^ Meyerguz, L; Kleinberg, J; Elber, R (Jul 10, 2007). "The network of sequence flow between protein structures". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (28): 11627–32. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10411627M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0701393104. PMC 1913895. PMID 17596339.

- ^ Karplus, M (Jun 17, 2011). "Behind the folding funnel diagram". Nature Chemical Biology. 7 (7): 401–4. doi:10.1038/nchembio.565. PMID 21685880.

- ^ Tokuriki, N; Stricher, F; Schymkowitz, J; Serrano, L; Tawfik, DS (Jun 22, 2007). "The stability effects of protein mutations appear to be universally distributed". Journal of Molecular Biology. 369 (5): 1318–32. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2007.03.069. PMID 17482644. S2CID 24638570.

- ^ Shakhnovich, BE; Deeds, E; Delisi, C; Shakhnovich, E (Mar 2005). "Protein structure and evolutionary history determine sequence space topology". Genome Research. 15 (3): 385–92. arXiv:q-bio/0404040. doi:10.1101/gr.3133605. PMC 551565. PMID 15741509.

- ^ Monsellier, E; Chiti, F (Aug 2007). "Prevention of amyloid-like aggregation as a driving force of protein evolution". EMBO Reports. 8 (8): 737–42. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7401034. PMC 1978086. PMID 17668004.

- ^ Fink, AL (1998). "Protein aggregation: folding aggregates, inclusion bodies and amyloid". Folding & Design. 3 (1): R9–23. doi:10.1016/s1359-0278(98)00002-9. PMID 9502314.

- ^ Richardson, JS; Richardson, DC (Mar 5, 2002). "Natural beta-sheet proteins use negative design to avoid edge-to-edge aggregation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (5): 2754–9. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.2754R. doi:10.1073/pnas.052706099. PMC 122420. PMID 11880627.

- ^ Müller MM, Allison JR, Hongdilokkul N, Gaillon L, Kast P, van Gunsteren WF, Marlière P, Hilvert D (2013). "Directed evolution of a model primordial enzyme provides insights into the development of the genetic code". PLOS Genetics. 9 (1): e1003187. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003187. PMC 3536711. PMID 23300488.

- ^ Firnberg, E; Ostermeier, M (Aug 2013). "The genetic code constrains yet facilitates Darwinian evolution". Nucleic Acids Research. 41 (15): 7420–8. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt536. PMC 3753648. PMID 23754851.

- ^ a b Lagha, Mounia; Bothma, Jacques P.; Levine, Michael (2012). "Mechanisms of transcriptional precision in animal development". Trends in Genetics. 28 (8): 409–416. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2012.03.006. PMC 4257495. PMID 22513408.

- ^ Perry, Michael W.; Boettiger, Alistair N.; Bothma, Jacques P.; Levine, Michael (2010). "Shadow Enhancers Foster Robustness of Drosophila Gastrulation". Current Biology. 20 (17): 1562–1567. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2010.07.043. PMC 4257487. PMID 20797865.

- ^ Zeitlinger, Julia; Stark, Alexander; Kellis, Manolis; Hong, Joung-Woo; Nechaev, Sergei; Adelman, Karen; Levine, Michael; Young, Richard A (11 November 2007). "RNA polymerase stalling at developmental control genes in the Drosophila melanogaster embryo". Nature Genetics. 39 (12): 1512–1516. doi:10.1038/ng.2007.26. PMC 2824921. PMID 17994019.

- ^ Nien, Chung-Yi; Liang, Hsiao-Lan; Butcher, Stephen; Sun, Yujia; Fu, Shengbo; Gocha, Tenzin; Kirov, Nikolai; Manak, J. Robert; Rushlow, Christine; Barsh, Gregory S. (20 October 2011). "Temporal Coordination of Gene Networks by Zelda in the Early Drosophila Embryo". PLOS Genetics. 7 (10): e1002339. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002339. PMC 3197689. PMID 22028675.

- ^ Morata, Ginés; Ripoll, Pedro (1975). "Minutes: Mutants of Drosophila autonomously affecting cell division rate". Developmental Biology. 42 (2): 211–221. doi:10.1016/0012-1606(75)90330-9. PMID 1116643.

- ^ Clavería, Cristina; Giovinazzo, Giovanna; Sierra, Rocío; Torres, Miguel (10 July 2013). "Myc-driven endogenous cell competition in the early mammalian embryo". Nature. 500 (7460): 39–44. Bibcode:2013Natur.500...39C. doi:10.1038/nature12389. PMID 23842495. S2CID 4414411.

- ^ Sancho, Margarida; Di-Gregorio, Aida; George, Nancy; Pozzi, Sara; Sánchez, Juan Miguel; Pernaute, Barbara; Rodríguez, Tristan A. (2013). "Competitive Interactions Eliminate Unfit Embryonic Stem Cells at the Onset of Differentiation". Developmental Cell. 26 (1): 19–30. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2013.06.012. PMC 3714589. PMID 23867226.

- ^ Xiong, Fengzhu; Tentner, Andrea R.; Huang, Peng; Gelas, Arnaud; Mosaliganti, Kishore R.; Souhait, Lydie; Rannou, Nicolas; Swinburne, Ian A.; Obholzer, Nikolaus D.; Cowgill, Paul D.; Schier, Alexander F. (2013). "Specified Neural Progenitors Sort to Form Sharp Domains after Noisy Shh Signaling". Cell. 153 (3): 550–561. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.023. PMC 3674856. PMID 23622240.

- ^ Akieda, Yuki; Ogamino, Shohei; Furuie, Hironobu; Ishitani, Shizuka; Akiyoshi, Ryutaro; Nogami, Jumpei; Masuda, Takamasa; Shimizu, Nobuyuki; Ohkawa, Yasuyuki; Ishitani, Tohru (17 October 2019). "Cell competition corrects noisy Wnt morphogen gradients to achieve robust patterning in the zebrafish embryo". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 4710. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10.4710A. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-12609-4. PMC 6797755. PMID 31624259.

- ^ Kesavan, Gokul; Hans, Stefan; Brand, Michael (2019). "Cell-fate plasticity, adhesion and cell sorting complementarily establish a sharp midbrain-hindbrain boundary" (PDF). bioRxiv. 147 (11). doi:10.1101/857870. PMID 32439756.

- ^ Eldar, Avigdor; Rosin, Dalia; Shilo, Ben-Zion; Barkai, Naama (2003). "Self-Enhanced Ligand Degradation Underlies Robustness of Morphogen Gradients". Developmental Cell. 5 (4): 635–646. doi:10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00292-2. PMID 14536064.

- ^ Ibañes, Marta; Belmonte, Juan Carlos Izpisúa (25 March 2008). "Theoretical and experimental approaches to understand morphogen gradients". Molecular Systems Biology. 4 (1): 176. doi:10.1038/msb.2008.14. PMC 2290935. PMID 18364710.

- ^ Eldar, Avigdor; Dorfman, Ruslan; Weiss, Daniel; Ashe, Hilary; Shilo, Ben-Zion; Barkai, Naama (September 2002). "Robustness of the BMP morphogen gradient in Drosophila embryonic patterning". Nature. 419 (6904): 304–308. Bibcode:2002Natur.419..304E. doi:10.1038/nature01061. PMID 12239569. S2CID 4397746.

- ^ Genikhovich, Grigory; Fried, Patrick; Prünster, M. Mandela; Schinko, Johannes B.; Gilles, Anna F.; Fredman, David; Meier, Karin; Iber, Dagmar; Technau, Ulrich (2015). "Axis Patterning by BMPs: Cnidarian Network Reveals Evolutionary Constraints". Cell Reports. 10 (10): 1646–1654. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2015.02.035. PMC 4460265. PMID 25772352.

- ^ Al Asafen, Hadel; Bandodkar, Prasad U.; Carrell-Noel, Sophia; Reeves, Gregory T. (2019-08-19). "Robustness of the Dorsal morphogen gradient with respect to morphogen dosage" (PDF). doi:10.1101/739292.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Masel J Siegal ML (2009). "Robustness: mechanisms and consequences". Trends in Genetics. 25 (9): 395–403. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2009.07.005. PMC 2770586. PMID 19717203.

- ^ Wilke, CO; Wang, JL; Ofria, C; Lenski, RE; Adami, C (Jul 19, 2001). "Evolution of digital organisms at high mutation rates leads to survival of the flattest" (PDF). Nature. 412 (6844): 331–3. Bibcode:2001Natur.412..331W. doi:10.1038/35085569. PMID 11460163. S2CID 1482925.

- ^ Van Dijk; Van Mourik, Simon; Van Ham, Roeland C. H. J.; et al. (2012). "Mutational Robustness of Gene Regulatory Networks". PLOS ONE. 7 (1): e30591. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...730591V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0030591. PMC 3266278. PMID 22295094.

- ^ van Nimwegen E, Crutchfield JP, Huynen M (1999). "Neutral evolution of mutational robustness". PNAS. 96 (17): 9716–9720. arXiv:adap-org/9903006. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.9716V. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.17.9716. PMC 22276. PMID 10449760.

- ^ Montville R, Froissart R, Remold SK, Tenaillon O, Turner PE (2005). "Evolution of mutational robustness in an RNA virus". PLOS Biology. 3 (11): 1939–1945. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030381. PMC 1275523. PMID 16248678.

- ^ Masel J, Maughan H; Maughan (2007). "Mutations Leading to Loss of Sporulation Ability in Bacillus subtilis Are Sufficiently Frequent to Favor Genetic Canalization". Genetics. 175 (1): 453–457. doi:10.1534/genetics.106.065201. PMC 1775008. PMID 17110488.

- ^ a b Bloom, JD; Lu, Z; Chen, D; Raval, A; Venturelli, OS; Arnold, FH (Jul 17, 2007). "Evolution favors protein mutational robustness in sufficiently large populations". BMC Biology. 5: 29. arXiv:0704.1885. Bibcode:2007arXiv0704.1885B. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-5-29. PMC 1995189. PMID 17640347.

- ^ a b Bershtein, Shimon; Goldin, Korina; Tawfik, Dan S. (June 2008). "Intense Neutral Drifts Yield Robust and Evolvable Consensus Proteins". Journal of Molecular Biology. 379 (5): 1029–1044. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.024. PMID 18495157.

- ^ Meiklejohn CD, Hartl DL (2002). "A single mode of canalization". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 17 (10): 468–473. doi:10.1016/s0169-5347(02)02596-x.

- ^ Ancel LW, Fontana W (2000). "Plasticity, evolvability, and modularity in RNA". Journal of Experimental Zoology. 288 (3): 242–283. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.43.6910. doi:10.1002/1097-010X(20001015)288:3<242::AID-JEZ5>3.0.CO;2-O. PMID 11069142.

- ^ Szöllősi GJ, Derényi I (2009). "Congruent Evolution of Genetic and Environmental Robustness in Micro-RNA". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 26 (4): 867–874. arXiv:0810.2658. doi:10.1093/molbev/msp008. PMID 19168567. S2CID 8935948.

- ^ Wagner GP, Booth G, Bagheri-Chaichian H (1997). "A population genetic theory of canalization". Evolution. 51 (2): 329–347. doi:10.2307/2411105. JSTOR 2411105. PMID 28565347.

- ^ Lehner B (2010). "Genes Confer Similar Robustness to Environmental, Stochastic, and Genetic Perturbations in Yeast". PLOS ONE. 5 (2): 468–473. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...5.9035L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009035. PMC 2815791. PMID 20140261.

- ^ a b Draghi, Jeremy A.; Parsons, Todd L.; Wagner, Günter P.; Plotkin, Joshua B. (2010). "Mutational robustness can facilitate adaptation". Nature. 463 (7279): 353–5. Bibcode:2010Natur.463..353D. doi:10.1038/nature08694. PMC 3071712. PMID 20090752.

- ^ a b Wagner, A. (2008). "Robustness and evolvability: A paradox resolved". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 275 (1630): 91–100. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1137. JSTOR 25249473. PMC 2562401. PMID 17971325.

- ^ Masel J, Trotter MV (2010). "Robustness and evolvability". Trends in Genetics. 26 (9): 406–414. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2010.06.002. PMC 3198833. PMID 20598394.

- ^ a b Aldana; Balleza, E; Kauffman, S; Resendiz, O; et al. (2007). "Robustness and evolvability in genetic regulatory networks". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 245 (3): 433–448. Bibcode:2007JThBi.245..433A. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2006.10.027. PMID 17188715.

- ^ Ebner, Marc; Shackleton, Mark; Shipman, Rob (2001). "How neutral networks influence evolvability". Complexity. 7 (2): 19–33. Bibcode:2001Cmplx...7b..19E. doi:10.1002/cplx.10021.

- ^ Babajide; Hofacker, I. L.; Sippl, M. J.; Stadler, P. F.; et al. (1997). "Neutral networks in protein space: A computational study based on knowledge-based potentials of mean force". Folding & Design. 2 (5): 261–269. doi:10.1016/s1359-0278(97)00037-0. PMID 9261065.

- ^ van Nimwegen and Crutchfield (2000). "Metastable evolutionary dynamics: Crossing fitness barriers or escaping via neutral paths?". Bulletin of Mathematical Biology. 62 (5): 799–848. arXiv:adap-org/9907002. doi:10.1006/bulm.2000.0180. PMID 11016086. S2CID 17930325.

- ^ Ciliberti; et al. (2007). "Innovation and robustness in complex regulatory gene networks". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 104 (34): 13591–13596. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10413591C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0705396104. PMC 1959426. PMID 17690244.

- ^ Andreas Wagner (2008). "Neutralism and selectionism: a network-based reconciliation" (PDF). Nature Reviews Genetics. 9 (12): 965–974. doi:10.1038/nrg2473. PMID 18957969. S2CID 10651547.

- ^ Rajon, E.; Masel, J. (18 January 2013). "Compensatory Evolution and the Origins of Innovations". Genetics. 193 (4): 1209–1220. doi:10.1534/genetics.112.148627. PMC 3606098. PMID 23335336.

- ^ Bloom; et al. (2006). "Protein stability promotes evolvability". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103 (15): 5869–74. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103.5869B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0510098103. PMC 1458665. PMID 16581913.

- ^ Waddington CH (1957). The strategy of the genes. George Allen & Unwin.

- ^ Masel, J. (30 December 2005). "Cryptic Genetic Variation Is Enriched for Potential Adaptations". Genetics. 172 (3): 1985–1991. doi:10.1534/genetics.105.051649. PMC 1456269. PMID 16387877.

- ^ Masel, J (Sep 30, 2013). "Q&A: Evolutionary capacitance". BMC Biology. 11: 103. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-11-103. PMC 3849687. PMID 24228631.

- ^ Bianco, Simone (2022-04-01). "Artificial Intelligence: Bioengineers' Ultimate Best Friend". GEN Biotechnology. 1 (2). Mary Ann Liebert: 140–141. doi:10.1089/genbio.2022.29027.sbi. ISSN 2768-1572. S2CID 248313305.

- ^ Vaishnav ED, de Boer CG, Molinet J, Yassour M, Fan L, Adiconis X, Thompson DA, Levine JZ, Cubillos FA, Regev A (March 2022). "The evolution, evolvability and engineering of gene regulatory DNA". Nature. 603 (7901): 455–463. Bibcode:2022Natur.603..455V. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04506-6. PMC 8934302. PMID 35264797.