This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Moga district is one of the twenty-three districts in the state of Punjab, India. It became the 17th district of Punjab state on 24 November 1995, being cut from Faridkot district. Moga district is among the largest producers of wheat and rice in Punjab, India. People from Moga city and Moga district belong to the Malwa culture. The district is noted for being the homeland for a high-proportion of Indian Punjabi expatriates who emigrated abroad and their descendants, which has given it the nickname of "NRI district".[2]

Moga district | |

|---|---|

Gurudwara in Bagha Purana | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Headquarters | Moga |

| Area | |

• Total | 2,235 km2 (863 sq mi) |

| Population (2011) | |

• Total | 995,746 |

| • Density | 444/km2 (1,150/sq mi) |

| Languages | |

| • Official | Punjabi |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| HDI (2017) | |

| Website | moga |

Moga city, the headquarters of the district, is situated on Ferozpur-Moga-Ludhiana road. Moga is well-known for its Nestlé factory,[2][3] Adani Food Pvt Ltd[citation needed], and vehicle modifications[citation needed]. Highways connected with Moga are Jalandhar, Barnala, Ludhiana, Ferozpur, Kotkapura, Amritsar. Bus services and Railway services are well connected with some major cities like Ludhiana, Chandigarh, and Delhi.

Moga district is notable for its higher standards-of-living compared to neighbouring Punjabi districts, based upon metrics such as access to education, electrification, and medical-care.[4] Much of this is attributed to the economic development of the district in the agricultural sector, such as the dairy industry.[4]

Etymology

editThe name of Moga may be ultimately derived from the Indo-Scythian king, Maues, who invaded and ruled the area in the 1st century BCE after conquering the Indo-Greek polities of the region.[5] "Moga" is the Indianized form of "Maues".[6] Another theory states Moga was named after Moga of the Gill clan, who owned a jagir that was located on the present-day location of Moga city.[7]

History

editAncient era

editStructures and sites dating before the reign of the Mughal emperor Akbar are exceedingly rare due to the changing course of the Sutlej river throughout the centuries. As a result, very few sites dating back to antiquity have been uncovered in the local area of Moga. This effect is more pronounced in the western parts of the district.

The location of ancient villages and towns can be inferred to the present of mounds of earth, brick, and pottery that have been excavated called thehs. These mounds are evidence that the banks of the river were inhabited in ancient times. A number of coins have been discovered at the site of these mounds.[8]

Indus Valley Civilization

editSites identified as belonging to the Indus Valley Civilization have been discovered in the area. Scholars have linked these finds to other sites uncovered in the Rupnagar area of Punjab.[8][9][10]

Vedic period

editThe composition of the Rigveda is proposed to have occurred in the Punjab circa 1500 and 1200 BCE.[11]

Post-Vedic period (After 600 BCE)

editThe region of Moga belongs to the Malwai cultural zone, named after the ancient Malava tribe who inhabited the area in ancient times.[12] During the reign of Porus in the 4th century BCE, the southern area of Punjab was ruled by both the Kshudrakas and Malavas. Some scholars believe they were pushed southwards due to martial and social pressures occurring in the north.[13] Alexander of Macedon warred with the Malavas for control of the region. This wrestle for power is recorded as being fierce and bitter in Greek historical accounts.[12] After the withdrawal of Macedonian forces in the area, the Malavas joined with anti-Greek forces to usurp Hellenistic power and control of the region, leading to the formation of the Mauryan dynasty.

The decline of the Mauryan dynasty coincided with an invasion of Bactrian Greeks, who successfully took control of the region in the second century BCE. This seizure of power in the Punjab by the Bactrians led to the migration of the Malavas from the area to Rajasthan, and from there to the now-called Malwa plateau of Central India.

Medieval era

editThe region of Moga is mentioned in Punjabi folklore.[14] The settlement of Moga (later a town and now a city) was established around 500-years-ago in around the late 15th or 16th century.[15]

The area is believed to have been under the writ of the Punwar clan of Rajputs during the early-mediaeval period.[16] They were headquartered in Janer, at the old riverbed location of the Sutlej river, over six kilometres north of the present-day city of Moga. Later on, the Bhati clan of Rajputs, originating from Jaisalmer, established themselves in the area, superseding the previous Punwars for authority of the region.

Jat tribes, who had been practicing migratory, nomadic-pastoralism for much of their recorded history, began to permanently settle the Moga area during this time and take up a sedentary lifestyle of settled agriculture.[17][18][19] First of them being the Dhaliwal clan, who firmly established themselves southeast of Moga at Kangar. They appear to have possibly obtained high repute, seeing as a woman of the clan, Dharm, who was the daughter of Chaudhary Mihr Mitha Dhaliwal, was wedded to the Mughal emperor Akbar.[20] The Gill clan of Jats, originally based in Bathinda, dispersed to the western parts of Moga district around this time. At the end of the 16th century, the Sidhu clan of Jats migrated northwards to the area from Rajasthan. A branch of the Sidhus, the Brars, established themselves in the south of Gill territory, pushing its former inhabitants northwards whilst taking control of their key places in the process. The Brars founded a chieftainship at Kot Kapura, 40 kilometres west of present-day Moga, and rebelled against the overlordship of Nawab Ise Khan, the Manj governor.

During the early Mughal-Sikh Wars, in 1634 Guru Hargobind left Amritsar to avoid Mughal persecution and arrived near Moga with fresh recruits enlisted en-route to stage a counter-attack against the Mughal government.[21] When near Moga, he sent his family to safety in Kartarpur and whilst he remained in the Malwa region with his army.[21]

Most of the Jat tribes of the local area were converted to Sikhism by the missionary works of the seventh Guru of the Sikhs, Har Rai.

At Dagru village in Moga district, it is believed Guru Har Rai stayed there for some time whilst on a tour of the Malwa region.[22] Gurdwara Tambu Sahib was later constructed to commemorate his stay in the area.[22]

According to Sikh tradition, the village of Dina located near the district's border with the neighbouring Bathinda district is where Guru Gobind Singh rested for a few days after the Second Battle of Chamkaur.[23] Furthermore, it is said he wrote and dispatched the Zafarnama letter to Aurangzeb from here.[23] Scholar Louis E. Fenech states the Guru rested at Dina at the house (specifically an upper story room called a chubārā) of a local Sikh named Bhai Desu Tarkhan after sending the Zafarnama from Kangar village, entrusted in the hands of Bhai Dharam Singh and Bhai Daya Singh.[24] A gurdwara, Zafarnama Gurdwara Lohgarh Sahib Pind Dina Patishahi Dasvin, commemorates his stay at Dina, Moga, and a sign there claims the Guru stayed at the location for 3 months and 13 days.[24] The Encyclopedia of Sikhism states the Guru only stayed at Dina for a few days conversely to the claims of the Gurdwara.[23] It further states that he stayed with two local Sikhs named Chaudhry Shamir and Lakhmir, the grandsons of a local cheiftain named Rai Jodh, who had served the sixth Sikh guru, Hargobind, and fought and died at the Battle of Mehraj.[23] Guru Gobind Singh gathered an army of hundreds of locals from Dina and the surrounding area and continued on his journey.[23]

In 1715 CE, Nawab Ise Khan, the Manj governor, stirred a rebellion against the Mughal hegemony but was defeated and killed. In 1760 CE, the ascendency of Sikh power became grounded after the defeat of Adina Beg, who was the last Mughal governor of Lahore.

Modern era

editSikh period

editThe Nishanwalia Misl was based in Singhanwala village of Moga district.[25][26] Bhuma Singh Dhillon, who succeeded as the second leader of the Bhangi Misl, was born in Hung village located in the Wadni parganah of Moga district.[27] The forces of Tara Singh, the misldar of the Dallewalia Misl of the Sikh Confederacy, led incursions into modern-day Moga district, conquering all the way to Ramuwala and Mari.[28] Fortresses (ਕਿਲਾ Kilā in Punjabi) were constructed at both of these places by the Sikh misl.[28] The local nawab of Kot Ise Khan in modern-day Moga district became a protectorate of the Ahluwalia Misl. In 1763-64, Gujar Singh, his brother Nusbaha Singh, and his two nephews, Gurbaksh Singh and Mastan Singh, of the Bhangi Misl, crossed the Sutlej river after a sacking of Kasur and gained control of the Firozepur area (including Moga) whilst Jai Singh Gharia, another band from the same quarters, seized Khai, Wan, and Bazidpur, and subordinated them.[8] Sada Kaur owned estates in Wadni, near modern-day Moga city.[29][30] The area of Moga was one of the 45 taluqas (subdistrict) south of the Sutlej River that was claimed by Maharaja Ranjit Singh as belonging to or claimed by him through Sada Kaur as per a list by Captain William Murray on 17 March 1828.[31] Kalsia State also held territory in the region.[32]

British period

editDuring the First Anglo-Sikh War, the forces of the Sikh Empire crossed the river Sutlej on 16 December 1845, and fought battles at Mudki, Firozshah, Aliwal, and Sabraon. The Sikh forces were defeated by the British and retreated back beyond the Sutlej. After the war, the British acquired all former territory of the Lahore Darbar south and east of the Sutlej. When the Sutlej campaign drew to a close at the end of 1846, the territories of Khai, Baghuwala, Ambarhar, Zira, and Mudki, with portions of Kot Kapura, Guru Har Sahai, Jhumba, Kot Bhai, Bhuchcho, and Mahraj were added to the Firozepur district. Other acquisitions by the British were divided between the Badhni and Ludhiana districts. In 1847, the Badhni district was dissolved and the following areas were incorporated into the Firozepur district: Mallanwala, Makhu, Dharmkot, Kot Ise Khan, Badhni, Chuhar Chak, Mari, and Sadasinghwala.[8]

During the Mutiny of 1857, there were reports of a Roman Catholic church being burnt down amongst other buildings of the colonial establishment in Firozepur district during sparks of tension.[33]

During the late 19th century, the Kuka movement was prevalent in the areas of Moga, with many of its followers drawing from the laypersons of the district.[34][35] The Kukas are believed to be one of the first resistance movement of the subcontinent towards Indian independence from European powers.[36]

In 1899, a co-educational school was founded in Moga (then in the Ferozpore district) by the Dev Samaj.[37]: 21 The Dev Samaj school was later upgraded to become the Dev Samaj High School.[38]

In 1901, the railway reached Moga locality and former jagir lands of Moga Gill were converted into the settlement.[7] At that era, Moga locality was an important location for the tea trade, which led to the coining of the phrase: Moga chah joga (meaning "Moga only has tea").[7]

In 1901, a plague was ravaging the local region, including Moga.[39] However, there were not enough huts established to treat victims and infected and non-infected persons were requested to congregate in the camps, increasing the infections.[39]

In 1894, the Christian missionary Rev. John Hyde, commonly known as "Praying Hyde", arrived in India and worked in the areas of Ferozepore and Moga.[40] In the early 20th century, a Christian missionary named Ray Harrison Carter drafted a "Moga plan" for the betterment of destitute Christian converts in Moga by establishing village schools and a training school focusing on agricultural education.[41] One of these educational institutions established by the Christian missionaries was the 'Moga Training School for Village Teachers', which was established in 1908 by the American Presbyterian Mission and conceived by Ray Harrison Carter.[42][43][44][45] The principal of the missionary school from 1914 to 1925 was William McKee, an American.[42][46] The institution focused on spreading Christianity throughout the villages of Moga.[42][43][44] Some of the missionaries who served at the institution were women, such as Arthur E. Harper and Irene Mason Harper.[44] Arthur Harper and Irene Harper, both Americans, served at the missionary institution from 1914 until their retirement in 1952.[46] The Moga School became renowned internationally for its approach to rural reconstruction by combining principles of self-help, character-building, and "practical agricultural demonstration", and it published its own periodical titled Village Teachers' Journal.[42][45]

In November 1914, two officials were shot dead in Moga by Ghadarites during a raid on a local treasury.[47] In March 1921, pro-Gandhi slogans were raised by passengers disembarking from a train at Moga, who refused to present their tickets to the station-master.[48]

In 1926, the Dayanand Mathra Dass College was established in present-day Moga city, making the city one of the few to have had an established college within it prior to independence.[note 1][7] Moga locality was the headquarters of eye-surgeon Mathra Das Pahwa, who established a hospital there in 1927, where he operated on cataract patients free-of-charge.[49][7][50][51] A large amount of cataract patients were treated over the years by Mathra Das Pahwa, with an operation of his being witnessed by Mahatma Gandhi.[52][53]

During the Indian Independence Movement, many revolutionaries came from Moga district. Many of them were tried and executed as a result of their activities against the colonial government.[54]

During the third Round Table Conference held in December 1932, the Akalis boycotted the talks so the colonial government sponsored Sardar Tara Singh of Moga as the Sikh representative to the talks.[note 2][37]: 177 Tara Singh of Moga was disowned by the Khalsa Darbar as a result of this.[37]: 177 In 1934, Malcolm Darling wrote that the settlement of Moga had a population of around 15,000 people.[55]

During a tour of Punjab in 1938, Nehru visited Moga town and met with Ghadar/Kirti leaders and socialist workers.[56]: 126

In September 1938, agrarian protestors in parts of present-day Moga district under Kalsia State back then were protesting excessive land revenue, requesting a reduction of them, when they were lathi-charged by state police.[57] The cattle fairs at Chirak village (that was held between 11 September 1938 and 20 September 1938) and Mari village was boycotted by the farmers' leaders, leading to a loss of revenue for Kalsia State.[57] This movement was known as the "Kalsia agitation" and around 125 were arrested and held at a jail in Chhachroli, in poor conditions.[57] Moga was the centre of the agitation.[57]

At the end of June in 1939, another agriculturalist movement arose in Chuhar Chak village over farmers wanting to stop paying the chowkidara tax, which had long been a demand.[56]: 182 A delegation of the farmers sent to Moga town to meet with the tehsildar were arrested for tax non-payment.[56]: 182 With news spreading of the arrests, jathas arrived in Moga from Chuhar Chak village and over a period of a few days, around 350 people (incl. 50 women) courted arrest.[56]: 182 The agitation effectively wanted to end payment of land revenue.[56]: 182 However, the Punjab Kisan Committee, distracted by other concerns at the time involving the Lahore Kisan Morcha, and not wanting to divert more of its resources, suspended the Chuhar Chak agitation by commanding the local committee to stop it.[56]: 182

Partition of Punjab

editLeading up to the partition of Punjab in 1947, the Sikhs of Moga were considered "battle-ready".[58] Prior to partition, Moga tehsil was one of the only two tehsils of British Punjab that had a Sikh-majority, with the other being Tarn Taran tehsil.[59] Whilst travelling around tehsils of Punjab, Professor Quraishi of the Muslim League was preparing a list of tehsils based on their religious composition, with Muslim-majority areas being considered grounds for areas of inclusion into a conceptual Pakistan.[60] However, the list notes that Moga was "predominantly Hindu".[60] In July 1947, 80,000 ruppees were collected from the Moga grain market to purchase weapons to be used against local Muslims of Moga.[61] Furthermore, an Akali martyr squad named Khalsa Sewak Dal was organized.[61] The Hindu organization, Rashtriya Sawayamsevak Sangh (R.S.S.), also made a resolve against the Muslims of Moga.[61] A local Muslim League leader named Sukh Annyat hired trucks and left the city with property and family.[61] However, his brother Hadayat Khan was murdered in the violence of partition by the son of an RSS leader named Lala Ram Rakha Sud, who was in-charge of the local RSS outfit.[61] On 1 August 1947, Sikhs massacred eighteen Muslim villagers in Kokri village and the murderers were absolved by the Ferozepore Deputy Commissioner, by claiming the Muslims were murdered over "mutual conflict over a relationship".[61] The next day on 2 August 1947, six Muslim mendicants were murdered near the Ludhiana-Moga railway line, with the deceased victims being accused of being bomb-makers.[61] News of these two incidents created further communal tensions in the region, especially amongst the rural villages, with Sikhs and Hindus being pitted against Muslims and vice-versa.[61] The advice of village elders appealing for calm was ignored, and violence, looting, and killing erupted in the area.[61] The Muslim-majority village of Athhur (Hatur) assaulted the Sikhs, with all of the inhabitants of the village being butchered in the aftermath after three days of fighting.[61] In Pato Hira Singh village, around 250 Muslim inhabitants were murdered.[61] Curfew was put in-place on 17 August 1947, however by 23 August 1947, there were reportedly no Muslims to be found any longer in Moga town and the surrounding villages, with the former Muslims having fled as refugees over the Radcliffe Line into Western Punjab.[61] When Robert Atkins visited Moga town during the partition of India, he recounts that he witnessed mutilated bodies strewn over the town resulting from a massacre that occurred there.[62] Moga was one of the regions of the Punjab that had experienced heavy losses in human lives and property during the partition.[63]

Post-independence

editAfter the partition of Punjab, a total of 349,767 refugees from what became Pakistan settled in Ferozepore district (which at that time included Moga and Muktsar tehsils which were later transferred to Faridkot district in 1972), as per the 1951 census of India.[64] Much of these refugees hailed from Bahawalpur State, and the districts of Montgomery, Sheikhupura, Lyallpur, and Lahore, whom crossed over the border into Ferozepore district.[64] Eighty percent of these refugees settled in the rural parts of Ferozepore district but around twenty percent settled in urban areas.[64]

On 24 September 1954, the 12th session of the All India Kisan Sabha (AIKS) was held at Moga, with a decision to form an organization that was separate from the AIKS being decided at the meeting.[65]

Due to the protectionist policies of the Indian government that required international firms to set-up local production in some industries, the Nestlé company decided to establish its first Indian factory at Moga in 1961.[4] The factory began service on 9 February 1962.[66] According to Hwy-Chang Moon, the establishment of the Nestlé factory led to an increase of development in the district.[4] In the early 1960's, the Moga area was poor and undeveloped, with there being a dearth of infrastructure (such as electricity, transportation, telephones, or medical-care) and the typical agricultural family owned less than five acres of poorly-irrigated land that had low fertility.[4] Nestlé initially could only procure dairy from 180 local farmers.[4] The typical household only had access to poor-quality milk that was oftentimes contaminated and could not be transported faraway, due to a lack of refrigeration, poor transportation, and the non-existence of quality control of dairy.[4] Whilst local families kept livestock, they typically only had one cow that could only produce enough milk to meet the familial needs and most calves did not survive to adulthood.[4] Thus, Moon argues that with the coming of Nestlé into the local area, the company brought-in experts (including veterinarians, nutritionists, agronomists, etc.), educated the local populace on modern animal husbandry and agriculture through monthly training sessions (teaching them modern dairy farming techniques, irrigation, and crop-management practices), and developed the local infrastructure.[4] With these financial and technological investments, it allowed local farmers to dig deeper wells that improved irrigation, and soon farmers were producing surpluses of crops and the survival rates of livestock increased, increasing the development of the area.[4] Nestlé also helped with the construction of local village-schools, drinking-water facilities, and toilets, in the area and provided the local farmers with cattle-feed, fodder seeds, veterinary medicines, mineral mixtures, and bank loans.[4] With the quality of milk in the area being improved, Nestlé started paying local producers higher amounts for their products than what was set by the Indian government, with the company purchasing at biweekly intervals and this income for farmers helping them get bank credit.[4] The company also helped establish clinics to help tuberculosis patients.[4] Moon describes the situation as a win-win, with Nestlé profiting from the expanded local market whilst locals benefit from the economic and infrastructural development of the region.[4] All of this led to the development of an industrial cluster at Moga.[4]

An event called the All-India Workers' Conference was held in Moga in September 1968, establishing the Bharatiya Khet Mazdoor Union with a membership of 251,000 at the time.[67][68] The areas of Moga district were heavily effected by Communist insurgencies in the latter half of the 20th century, being one of the worst affected areas of the state of Punjab.[69]

On 5 October 1972, a group of people were protesting against the black marketing of tickets at a movie theatre in Moga when police opened fire on them, leading to the deaths of four people.[70] Two students, Harjit Singh and Swarn Singh of Charrik village, and passersbys Gurdev Singh and Kewal Krishan, were killed in the police firing, near Regal Cinema in Moga.[14][7][70] The incident lead to a movement known as the Moga agitation, a student movement which was led by leftist groups where protestors set afire government buildings and public transport for two months.[note 3][71][72][73][14][7][74] The student movement had ramifications throughout the Punjab.[75][74] The Punjab Students Union (PSU) was formed the same year.[70] In 1972, PSU president Iqbal Khan and general secretary Pirthipal Singh Randhawa led protests against the price rise and the black marketing of cinema tickets.[70] A library would later be established at former location of Regal Cinema to commemorate the martyred students.[14] The incident has been likened to the earlier Jallianwala Bagh massacre of 1919.[7] At the Moga Sangram Rally of 1974, the Congress-run government of Indira Gandhi was challenged.[70] The PSU later opposed the bus fare hike in 1979.[70]

In the 1970's, the historical fortress of Sada Kaur at Wadhni (south of Moga city) was demolished and a gurdwara and statue honouring Sada Kaur was erected at the location of the destroyed fort.[30]

During the period of Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, a common story that Bhindranwale told was about a Sikh girl being stripped naked by Hindus in a village near Moga, with the girl's father supposedly being forced to engage in intercourse with her.[76] However, when Bhindranwale was pressed for further details to investigate and conform the story, he became agitated and hostile.[76] During the time period of Dharam Yudh Morcha, Sikh militants (and allegedly foreign personnel) were sheltering in gurdwaras in Moga town, thus an order was given on 30 May that the temples should be sieged by BSF paramilitary forces until the militants inside them surrendered, however the Sikh priests of Amritsar protested the siege and threatened to lead a march toward Moga.[77][78][79] The government eventually backed-down and doing so may have emboldened Bhindranwale and his followers to hole-up in Sikh shrines.[79]

On 26 June 1989, during the Punjab insurgency, an event known as the Moga massacre occurred, when suspected Khalistani militants opened fire on RSS workers undergoing a morning exercise and indoctrination session in Nehru Park in Moga city.[80] The attack led to the deaths of 24 people and was suspected of being carried out by the Khalistan Commando Force.[80] Moga district also experienced encounter-killings during the insurgency, such as the case of Bharpur Singh (aged 21), Bobby Monga, and Satnam Singh, on the Moga-Talwandi road at Khukhrana village on 27–28 December 1990.[81][82] The three were travelling together through Moga when a police group led by Mangal Singh indiscriminately fired on them, killing Bharpur and Bobby but Satnam survived, with the police characterizing the incident as "cross firing between the police and militants".[82]

In 1996, at a historic conference in Moga known as the Moga Conference, the Shiromani Akali Dal adopted a moderate Punjabi agenda and shifted its party headquarters from Amritsar to Chandigarh.[83][84]

In 2003, Gursewak Singh Sodhi of Dhilwana Kalan village in Moga district was reprimanded by the SGPC for sending turban and clothing relics of Guru Gobind Singh to Canada to be displayed, in-exchange for money and gold.[85]

In March 2013, around over 150 farmers were arrested during an agitation in the state.[86] During the 2020–2021 Indian farmers' protest, many of the participants of the movement against the three farm bills hailed from Moga district.[87][88] In-fact, the 2020–21 Indian farmers' protest originated from Moga, where 32 farmers' unions resolved to oppose the three farm bills and launch a protest against them.[89]

The Guru Granth Sahib Bagh is an initiative of EcoSikh, working in-collaboration with PETALS, regarding the establishment and upkeeping of a garden near the historical Sikh shrine, Gurusar Sahib, located in Moga district.[90] The garden was inaugurated in September 2021 and contains all fifty-eight plant species that find mention by name within the hymns of the Guru Granth Sahib.[90] Each plant is accompanied by a stone with an engraving containing the relevant excerpt from the Sikh scripture mentioning the specie.[90]

In April 2023, Sikh leader Amritpal Singh was arrested in a gurdwara in Moga city.[91]

Creation of district

editOriginally, Moga used to be part of the Ferozepur district, but it was bifurcated and the then tehsils of Moga and Muktsar were transferred to the then-newly created Faridkot district on 7 August 1972.[92] From that point onwards, Moga was a subdivision of Faridkot district until the then Chief Minister of Punjab, Harcharan Singh Brar, agreed to the public request to make Moga a district on 24 November 1995.[2][14] The judicial court system of Moga district was tied to Faridkot' district's until Saturday, 28 April 2012, when it was officially separated in-order to speed-up the processing of judicial cases and ease the workload.[7]

Administrative divisions

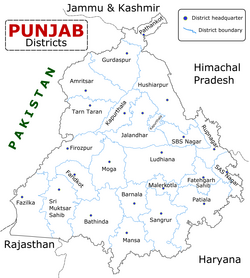

editMoga district, which occupies 2,216 square kilometres, is divided into two tehsils, two sub-tehsils, and four community development blocks.[14][7] The two tehsils are: Bagha Purana and Nihal Singh Wala tehsils.[7] The two sub-tehsils are: Badhni Kalan and Dharamkot sub-tehsils.[7] Moga city is the headquarters of the district.[14] The district contains around three towns and 180 villages.[14] Moga is bordered by Ferozepur district to the north, Ludhiana district to the east, Sangrur district to the southeast, Bathinda district to the south, and Faridkot district to the west.[14][7] Moga district is interconnected through roadways and railways to its neighbouring districts.[14] A railway connects Ferozepur, Moga, and Ludhiana districts together.[14] Moga district itself is part of the Firozpur division.[7]

Localities

editThe towns of Bagha Purana, Badhni Kalan, Dharamkot, Kot Ise Khan, Nihal Singh Wala and Ghal Kalan fall in Moga district.[citation needed] The villages like Rattian Khosa Randhir, Dhalleke, Thathi Bhai, Rajiana, Dunne Ke, Landhe Ke, Samadh Bhai, Kotla Rai-ka, Bhekha, Bughipura, Daudhar, Dhudike, Lopon, Himmatpura, Manooke, Bahona, and Chugawan, also fall within this district.[citation needed] Takhtupura Sahib is one of the well-known villages in this district.[citation needed] Takhtupura Sahib is a historical village.[citation needed]

Bagha Purana lies on the main road connecting Moga and Faridkot and thus is a major hub for buses to all across Punjab.[citation needed] Bagha Purana's police station has the largest jurisdiction in Punjab; over 65 'pinds' or villages are within its control.[citation needed] The town is basically divided into 3 'pattis' or sections: Muglu Patti (the biggest one), Bagha Patti, and Purana Patti.[citation needed] The town has its fair share of rich people and thus the standard of living is above average as compared to the surrounding towns and villages.[citation needed]

Dharamkot is a city and a municipal council in the Moga district.[citation needed] Daudhar is the largest village in Moga.[citation needed]

Culture

editThe local dialect of Punjabi is spoken by local inhabitants.[14]

Religious sites

editMany historical gurdwaras associated with the Sikh gurus can be found in Moga district.[14] There are gurdwaras associated with Guru Hargobind, Guru Har Rai, and Guru Gobind Singh, to be found in the district.[14] There is a Punjabi folk shrine dedicated to the folk deity Lakhdata in Langiana village in Moga district.[93] Shrines dedicated to Lakhdata are known as nigaha.[94] A dhuna dedicated to Sri Chand can be found in Korewal village in Daroli Baike in Moga district, which as per oral tradition was established by a roaming sadhu.[95]

-

Gurdwara Seetal Sar, Nangal, Moga district, Punjab

-

Shiv Mandir at Moga Road, Bagha Purana

-

Yaadgaar Babu Rajab Ali Khan, Sahoke village, Moga district, Punjab

Festivals

editTraditional celebrations, observations, and festivals include Guru Nanak Gurpurab, Guru Gobind Singh Gurpurab, Guru Arjan Shaheedi Diwas, Guru Tegh Bahadur Shaheedi Diwas, Basant, Vaisakhi, Hola Maholla, Shivratri, Ram Naumi, Janmashtami, Tis, Gugga Naumi.[14] At Dina village, Zafarnama Diwan is also celebrated.[14]

Demographics

edit| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1951 | 379,181 | — |

| 1961 | 443,135 | +1.57% |

| 1971 | 536,623 | +1.93% |

| 1981 | 655,873 | +2.03% |

| 1991 | 777,894 | +1.72% |

| 2001 | 894,793 | +1.41% |

| 2011 | 995,746 | +1.07% |

| source:[96] | ||

In the 2001 census, Moga had a population of 886,313.[14] According to the 2011 census Moga district has a population of 995,746,[97] roughly equal to the nation of Fiji[98] or the US state of Montana.[99] This gives it a ranking of 447th in India (out of a total of 640).[97] The district has a population density of 444 inhabitants per square kilometre (1,150/sq mi) .[97] Its population growth rate over the decade 2001-2011 was 10.9%.[97] Moga has a sex ratio of 893 females for every 1000 males,[97] and a literacy rate of 71.6%. Scheduled Castes made up 36.50% of the population.[97]

Gender

editThe table below shows the sex ratio of Moga district through decades.

| Census year | Ratio |

|---|---|

| 2011 | 893 |

| 2001 | 887 |

| 1991 | 884 |

| 1981 | 881 |

| 1971 | 866 |

| 1961 | 862 |

| 1951 | 867 |

The table below shows the child sex ratio of children below the age of 6 years in the rural and urban areas of Moga district.

| Year | Urban | Rural |

|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 853 | 863 |

| 2001 | 802 | 822 |

Languages

editAt the time of the 2011 census, 96.21% of the population spoke Punjabi and 3.21% Hindi as their first language.[102]

Religion

editThe district have the second highest percentage of Sikhs by district in Punjab, after Taran Taran (according to 2001 census).

The table below shows the population of different religions in absolute numbers in the urban and rural areas of Moga district.[104]

| Religion | Urban (2011) | Rural (2011) | Urban (2001) | Rural (2001) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sikh | 1,20,975 | 6,97,946 | 98,934 | 6,68,835 |

| Hindu | 1,00,170 | 58,244 | 76,916 | 40,870 |

| Muslim | 1,874 | 7,514 | 968 | 5,028 |

| Christian | 1,844 | 1,433 | 1,501 | 1,063 |

| Other religions | 2,383 | 3,363 | 321 | 420 |

Economy

editThe income of Municipalities and Municipal corporations in Moga district from municipal rates and taxes in the year 2018 was 577,781 thousand rupees.[105] Much of the economic development of the district is attributed to the Nestlé factory, with an industrial cluster forming to support the dairy industry, consisting of competing dairy farms and factories.[4] Nestlé purchases dairy from over 75,000 local farmers in the district, collecting twice a day from more than 650 village dairies.[4] In 2012, the Nestlé factory directly employed around 2,400 people, with a further 86,371 people being provided employment through Nestlé's main suppliers.[106]

Agriculture

editThe local economy of Moga is dominated by the agricultural sector, with 90% of the land of the district being considered agricultural land.[14] The main staples of crop grown in Moga's farms are wheat, cumin, maize, barley, and millet.[14] Cotton, oilseeds, and potatoes are also cultivated, to a lesser extent.[14] The district exports much of the food-grains grown in it.[14] The grain markets of Moga are prominent, where surplus stocks of wheat, rice, pulses, oil-seeds, and cotton, are on sale.[14]

The main kind of livestock kept in Moga are cows, buffalos, bullocks, horses, mules, sheep, and goats.[14] The district contains a cattle hospital.[14]

Industry

editMany factories in the state are for making agricultural-related products, nut-bolts, mustard-oil, engine-oil, coffee, condensed-milk, and footwear.[14] The district contains a Nestlé factory.[14] The Nestlé factory produces milk, milk-products, and maggi.[14] A surge of foreign-exhange coming into the district is related to the exporting of products such as motor-parts, cotton-seeds, oil-seeds, and nuts to international markets, such as Russia, the United Kingdom, the United States, Malaysia, Thailand, Poland, and others.[14]

In 2010-11, there were 2,850 registered Micro and Small Enterprise (MSE) units in Moga district, which provided employment to 21,218 people. There were 5 registered Medium and Large industrial units, which provided employment to 1,699 people.[107]

Politics

editIn 1952, before the delimitation exercise, Moga existed back then as Moga-Dharamkot constituency, which was represented by two candidates, Rattan Singh (Congress) and Devinder Singh (Akali Dal).[75] Moga tends to vote against the general trend.[75] In the last 14 elections that Moga assembly constituency had witnessed since 1952, the voters voted for the losing candidate at 12 elections.[75] It was only twice that the winning candidate from here belonged to the ruling party, with those candidates namely being Malti Thapar (Congress) in 1992 and Tota Singh of the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) in 1997.[75] Voters in the region do not generally vote based upon caste or religion.[75] Of the last fourteen MLAs, nine were Sikhs, with the remaining being Hindus: Sathi Rup Lal, Malti Thapar, and Joginderpal Jain.[75] The secular nature of the voters in the region has been attributed to the numerous social and political movements that occurred in Moga over the years.[75] On different occasions, the Akali Dal has launched their political campaigns from Moga before going for the assembly polls, such as in 1996, 2006, and 2011, before returning to power.[75][108] Moga has been described as a key place in Punjabi politics.[108] All three majors parties, SAD, Congress, and the AAP, place importance on starting their political rallies from Moga.[108] In September 2016, the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) released their manifesto at a political rally for farmers at Bagha Purana.[108]

List of MLAs per assembly constituency

edit| No. | Constituency | Name of MLA | Party | Bench | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 71 | Nihal Singh Wala (SC) | Manjit Singh Bilaspur | Aam Aadmi Party | Government | |

| 72 | Bhagha Purana | Amritpal Singh Sukhanand | Aam Aadmi Party | Government | |

| 73 | Moga | Dr. Amandeep Kaur Arora | Aam Aadmi Party | Government | |

| 74 | Dharamkot | Devinder Singh Laddi Dhos | Aam Aadmi Party | Government | |

Education

editMoga city is also known for its advanced number of educational institutes, such as middle, high, and senior secondary schools, colleges, and libraries.[14] The district also contains Ayurvedic colleges.[14] The district has two public libraries which contain reading-room facilities.[14]

Notable schools and colleges of Moga include:

- Baba Kundan Singh Memorial Law College

- Kitchlu Public School

- Shivalik Model Sen. Sec. School, Moga

Environment

editFlora

editThe district currently has a low amount of its area under forest cover, partly due to past deforestation during the Green Revolution,[109] but afforestation and reforestation drives have led to the planting of saplings in the district.[110] 9 million tree saplings are planned to be planted in the district before 2026 by NITI Aayog to meet the demands of a World Economic Forum initiative, with hopes of increasing Moga district's percentage of land under forest cover from the current 1.25% (2,575 hectares) to over 5% (11, 575 hectares).[110] In September 2021, a garden, named 'Guru Granth Sahib Bagh', was set-up in the historical village of Patto Hira Singh in the district. The garden is notable as it contains flora species mentioned in the Guru Granth Sahib, the primary Sikh canonical scripture and is intended on highlighting the connection between the Sikh Gurus and the natural world.[111]

Health

editMany ayurvedic and allopathic health facilities, such as dispensaries and hospitals, can be found in the district.[14] There are also regular hospitals and family-planning centres.[14]

The table below shows the data from the district nutrition profile of children below the age of 5 years, in Moga, as of year 2020.

| Indicators | Number of children (<5 years) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Stunted | 16,207 | 22% |

| Wasted | 8,818 | 12% |

| Severely wasted | 2,245 | 3% |

| Underweight | 12,365 | 17% |

| Overweight/obesity | 3,606 | 5% |

| Anemia | 46,467 | 70% |

| Total children | 73,602 |

The table below shows the district nutrition profile of Moga of women between the ages of 15 and 49 years, as of year 2020.

| Indicators | Number of women (15–49 years) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Underweight (BMI <18.5 kg/m^2) | 41,329 | 13% |

| Overweight/obesity | 101,378 | 33% |

| Hypertension | 95,952 | 31% |

| Diabetes | 45,699 | 15% |

| Anemia (non-preg) | 168,240 | 55% |

| Total women (preg) | 15,808 | |

| Total women | 307,737 |

The table below shows the current use of family planning methods by currently married women between the age of 15 and 49 years, in Moga district.

| Method | Total (2019–21) | Total (2015–16) | Rural (2015–16) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female sterilization | 25.6% | 37.5% | 38.9% |

| Male sterilization | 0.6% | 0.2% | 0.2% |

| IUD/PPIUD | 3.2% | 5.6% | 4.8% |

| Pill | 1.9% | 2.6% | 2.2% |

| Condom | 28.2% | 21.1% | 20.0% |

| Injectables | 0.0% | 0.6% | -- |

| Any modern method | 60.0% | 67.4% | 66.4% |

| Any method | 75.0% | 76.6% | 74.2% |

| Total unmet need | 8.0% | 6.4% | 7.4% |

| Unmet need for spacing | 2.7% | 2.2% | 2.7% |

The table below shows the number of road accidents and people affected in Moga district by year.

| Year | Accidents | Killed | Injured | Vehicles Involved |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 220 | 201 | 64 | 158 |

| 2021 | 193 | 185 | 95 | 181 |

| 2020 | 185 | 173 | 70 | 142 |

| 2019 | 135 | 110 | 92 | 145 |

Deputy Commissioners

editMoga district have following Deputy Commissioners so far:[116]

| # | Name | Assumed office | Left office | Tenure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Phulwant Singh Sidhu | 5 December 1995 | 4 December 1996 | 365 days |

| 2 | Cap. Narinder Singh | 4 December 1996 | 18 February 1997 | 76 days |

| 3 | R Venkatraman | 18 February 1997 | 28 April 1998 | 1 year, 69 days |

| 4 | K.S. Kang | 28 April 1998 | 3 June 1999 | 1 year, 36 days |

| 5 | K.B.S Sidhu | 3 June 1999 | 4 March 2002 | 2 years, 274 days |

| 6 | G. Raman Kumar | 4 March 2002 | 25 July 2004 | 2 years, 143 days |

| 7 | Mandeep Singh | 26 July 2004 | 6 April 2006 | 1 year, 254 days |

| 8 | V.K. Meena | 7 April 2006 | 9 October 2006 | 185 days |

| 9 | Arvinder Singh | 9 October 2006 | 23 December 2006 | 75 days |

| 10 | S.K. Sharma | 23 December 2006 | 12 March 2007 | 365 days |

| 11 | Arvinder Singh | 12 March 2007 | 6 November 2007 | 239 days |

| 12 | Satwant Singh | 7 November 2007 | 11 August 2010 | 2 years, 277 days |

| 13 | Vijay N. Zade | 11 August 2010 | 28 July 2011 | 351 days |

| 14 | Ashok Kumar Singla | 28 July 2011 | 28 December 2011 | 153 days |

| 15 | B. Purushertha | 28 December 2011 | 3 April 2012 | 97 days |

| 16 | Arshdeep Singh Thind | 3 April 2012 | 30 May 2014 | 2 years, 57 days |

| 17 | Parminder Singh Gill | 2 June 2014 | 5 January 2016 | 1 year, 217 days |

| 18 | Kuldeep Singh Vaid | 3 February 2016 | 30 November 2016 | 301 days |

| 19 | Parminder Singh Gill | 9 December 2016 | 5 January 2017 | 27 days |

| 20 | Parveen Kumar Thind | 6 January 2017 | 15 May 2017 | 129 days |

| 21 | Dilraj Singh | 16 May 2017 | 29 August 2018 | 1 year, 105 days |

| 22 | Devinderpal Singh Kharbanda | 29 August 2018 | 2 October 2018 | 34 days |

| 23 | Sandeep Hans | 3 October 2018 | 5 October 2021 | 3 years, 2 days |

| 24 | Dr. Harish Nayar | 5 October 2021 | 1 April 2022 | 178 days |

| 25 | Kulwant Singh | 3 April 2022 | 16 August 2024 | 2 years, 135 days |

| 26 | Vishesh Sarangal | 17 August 2024 | Till Date | 139 days |

Notable people

edit- Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, 14th head of the Sikh institution Damdami Taksal from village Rode

- Raj Brar, an Indian singer.

- Gurjant Singh Budhsinghwala, militant leader of the Khalistan Liberation Force which sought the freedom of Punjab through the use of arms

- Khem Singh Gill, an academic, geneticist, plant breeder and Vice-Chancellor of the Punjab Agricultural University, and receiver of Padma Bhushan award

- Lachhman Singh Gill, Chief Minister of Punjab from village Chuhar Chak

- Jaswant Singh Kanwal, Sahitya academic fellowship for the book 'Pakhi' 1996 and Sahitya Akademi award for 'Taushali Di Hanso' 1998. He was from Dhudike vill.

- Narinder Singh Kapany, Indian born American Physicist known for his work in fiber optics

- Harmanpreet Kaur, batter in the Indian Women's National Cricket Team and Captain of the T20 Indian Women's National Cricket Team

- Roshan Prince, actor and Singer

- Lala Lajpat Rai, an Indian freedom fighter from Village Dhudhike

- Baldev Singh, author, winner of the Sahitya Akademi Award

- Gurinder Singh, Fifth and Present Chief of Radha Soami Satsang Beas

- Joginder Singh, was an Indian Army soldier, and recipient of the Param Vir Chakra.

- Tota Singh former Punjab Education Minister and former Agriculture Minister

- Sonu Sood, Indian film actor

- Tajinderpal Singh Toor, a shot put athlete and Asian games gold medalist

- Fazal Deen, Battery Hawker.

See also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ "United Nations HDI report - Punjab". in.undp.org. 9 March 2012. Archived from the original on 16 October 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ a b c "Section 2: Different Districts of Punjab – Moga District". Discover Punjab: Attractions of Punjab. Parminder Singh Grover Moga, Davinderjit Singh, Bhupinder Singh. Ludhiana, Punjab, India: Golden Point Pvt Ltd. 2011.

Moga district is one of the nineteen districts in the state of Punjab in North West Republic of India. It became the 17th district of Punjab State on 24 November 1995. It is also known as NRI district. Most Punjabi Non-resident Indians (NRIs) belong to rural areas of Moga District, who immigrated to the USA, the UK and Canada in the last 30-40 years. 40-45% of the population of NRIs from Canada, the US and the UK belong to Moga district. Moga District is among the largest producers of wheat and rice in Punjab, India. People from Moga City and Moga District belong to the Malwa culture. Numerous attempts were previously made to make Moga a district but all were unsuccessful. Finally the then Chief Minister of Punjab S. Harcharan Singh Brar agreed to the public demand to make this a district on 24 November 1995. Before this, Moga was the subdivision of Faridkot district. Moga town, the headquarters of the district, is situated on Ferozpur-Ludhiana road.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Impact of Nestlé's Moga Factory on Surrounding Areas". Nestlé. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Moon, Hwy-Chang (9 August 2018). "7.5: Business Case: Nestlé's CSV Activities in India". The Art of Strategy: Sun Tzu, Michael Porter, and Beyond. Cambridge University Press. pp. 159–162. ISBN 9781108470308.

- ^ Samad, Rafi U. (2011). The Grandeur of Gandhara: The Ancient Buddhist Civilization of the Swat, Peshawar, Kabul and Indus Valleys. Algora Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87586-860-8.

- ^ Mārg̲. Vol. 37. Marg Publications. 1983. p. 22.

A copperplate inscription from Taxila speaks of 'the Great King, the Great Moga.' Moga is the Indianised form of Maues . Does the city of Moga in Punjab enshrine his name?

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "History". Moga District Court. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Punjab District Gazetteers - Chapter II History". yumpu.com. Department of Revenue, Government of Punjab. Retrieved 16 August 2022.

- ^ Frontiers of the Indus civilization : Sir Mortimer Wheeler commemoration volume. Mortimer Wheeler, B. B. Lal, S. P. Gupta. New Delhi: Published by Books & Books on behalf of Indian Archaeological Society jointly with Indian History & Culture Society. 1984. ISBN 0-85672-231-6. OCLC 11915695.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "History | District Faridkot, Government of Punjab | India". Retrieved 16 August 2022.

- ^ Flood, Gavin D. (1996). An introduction to Hinduism. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43304-5. OCLC 50516193.

- ^ a b Prakash, Buddha (1966). Glimpses of Ancient Panjab. Punjabi University, Department of Punjab Historical Studies.

- ^ Prakash, Buddha (1964). Political and Social Movements in Ancient Panjab (from the Vedic Age Upto [sic] the Maurya Period). M. Banarsidass.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag "ਮੋਗਾ [two separate entries for both the district and city]" [Moga]. Punjabipedia – Punjabi University, Patiala (entries sourced from 'Punjab Kosh' (vol. 2) by the Department of Languages, Punjab) (in Punjabi). 18 June 2018. Retrieved 14 July 2024.

- ^ "Siege at Moga". Link. 26 (4). United India Periodicals: 22. 1984.

Moga, a small town in Punjab, is about 500-years old ...

- ^ Cunningham, Alexander (14 September 2016). Archeological Survey of India Report of Tours in the Punjab in 1878-79 vol.14. Vol. XIV. Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). pp. 67–69. ISBN 978-1-333-58993-6.

- ^ Asher, Catherine B. (2006). India before Europe. Cynthia Talbot. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-80904-5. OCLC 61303480.

- ^ Nomads in the sedentary world. Anatoly M. Khazanov, André. Wink. London: Routledge. 2001. ISBN 978-0-203-03720-1. OCLC 820853396.

Hiuen Tsang gave the following account of a numerous pastoral-nomadic population in seventh-century Sin-ti (Sind): 'By the side of the river..[of Sind], along the flat marshy lowlands for some thousand li, there are several hundreds of thousands [a very great many] families ..[which] give themselves exclusively to tending cattle and from this derive their livelihood. They have no masters, and whether men or women, have neither rich nor poor.' While they were left unnamed by the Chinese pilgrim, these same people of lower Sind were called Jats' or 'Jats of the wastes' by the Arab geographers. The Jats, as 'dromedary men.' were one of the chief pastoral-nomadic divisions at that time, with numerous subdivisions, ....

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Wink, André (2004). Indo-Islamic society: 14th – 15th centuries. BRILL. pp. 92–93. ISBN 978-90-04-13561-1.

In Sind, the breeding and grazing of sheep and buffaloes was the regular occupations of pastoral nomads in the lower country of the south, while the breeding of goats and camels was the dominant activity in the regions immediately to the east of the Kirthar range and between Multan and Mansura. The jats were one of the chief pastoral-nomadic divisions here in early-medieval times, and although some of these migrated as far as Iraq, they generally did not move over very long distances on a regular basis. Many jats migrated to the north, into the Panjab, and here, between the eleventh and sixteenth centuries, the once largely pastoral-nomadic Jat population was transformed into sedentary peasants. Some Jats continued to live in the thinly populated barr country between the five rivers of the Panjab, adopting a kind of transhumance, based on the herding of goats and camels. It seems that what happened to the jats is paradigmatic of most other pastoral and pastoral-nomadic populations in India in the sense that they became ever more closed in by an expanding sedentary-agricultural realm.

- ^ Dalal, Sukhvir Singh (April 2013). "Jat Jyoti". Jat Jyoti. Jat Biographical Centre B-49, First Floor, Church Road, Joshi Colony, I. P. Extension Delhi 110092: Jat Biographical Centre: 7.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ a b Dhillon, Dalbir Singh (1988). Sikhism: Origin and Development. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors Pvt Limited. p. 122.

- ^ a b Singha, H.S. (2000). The Encyclopedia of Sikhism (Over 1000 Entries). Hemkunt Press. p. 194. ISBN 9788170103011.

1. Tambu Sahib, Dagru: It is situated in village Dagru near Moga and is dedicated to Guru Har Rai who encamped here in the course of his journey through the Malwa region.

- ^ a b c d e Singh, Harbans. The Encyclopedia of Sikhism. Vol. I: A-D. Punjabi University, Patiala. pp. 484–485.

- ^ a b Fenech, Louis E. (2013). The Sikh Zafar-namah of Guru Gobind Singh: A Discursive Blade in the Heart of the Mughal Empire. Oxford University Press. pp. 24–25. ISBN 9780199931439.

- ^ Sandhu, Jaspreet Kaur (2000). Sikh Ethos: Eighteenth Century Perspective. Vision & Venture. p. 55. ISBN 9788186769126.

- ^ Singh, Bhagat (1993). A History of the Sikh Misals. Publication Bureau, Punjabi University. pp. 259–261.

- ^ Gupta, Hari Ram (1999). History of The Sikhs: The Sikh Commonwealth or Rise and Fall of Sikh Misls. Vol. 4. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. p. 206. ISBN 9788121501651.

- ^ a b Gandhi, Surjit Singh (1999). Sikhs in the Eighteenth Century: Their Struggle for Survival. Singh Bros. p. 533. ISBN 9788172052171.

Tara Singh Ghaiba, a prominent leader of the Dallewalia Misl, extended his conquests as far as Ramuwala and Mari in the Moga tahsil at both of which places he built forts.

- ^ Gupta, Hari Ram (1978). History of the Sikhs: The Sikh Lion of Lahore, Maharaja Ranjit Singh, 1799-1839. Vol. 5 (3rd ed.). Munshiram Manoharlal. p. 51. ISBN 9788121505154.

- ^ a b Bansal, Bobby Singh (1 December 2015). Remnants of the Sikh Empire: Historical Sikh Monuments in India & Pakistan. Hay House. ISBN 9789384544935.

Sada Kaur, held vast estates in Batala and Mukerian, yet her extensive jagirs were also located in the cis-Sutlej territories at Wadhni, about 20km south of present day Moga town in Moga district. The ancestral fort of Sada Kaur had been demolished some forty years ago and the nanak-shahi bricks divided amongst her descendants. From all accounts it was a grand structure with magnificent arches and balconies. The wooden carved gates were equally impressive which required about 25 men to lift a single panel. A Sikh temple and a statue now stands in place of the fort in the memory of the gallant Sada Kaur who died incarceration at Amritsar in 1832 ...

- ^ Gupta, Hari Ram (1991). History of the Sikhs. Vol. 5. Munshiram Manoharlal. pp. 87–88. ISBN 9788121505154.

- ^ Historical Dictionary of Sikhism. Louis E. Fenech, W. H. McLeod (3rd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. 11 June 2014. p. 171. ISBN 9781442236011.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Punjab Government Records, Mutiny Reports. Vol. VIII. pp. Pt.I, pp. 47–57, pt.II, pp. 208–210, 331.

- ^ "Kukas. The Freedom Fighters of the Panjab. by Ahluwalia, M.M.: (1965) | John Randall (Books of Asia), ABA, ILAB". www.abebooks.com. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- ^ Yapp, M. E. (February 1967). "Fauja Singh Bajwa: Kuka movement: an important phase in Punjab's role in India's struggle for freedom. (Punjab History Forum Series, No. 1.) xvi, 236 pp., front., 11 plates. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, c 1965. Es. 20". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 30 (1): 208–209. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00099419. ISSN 0041-977X. S2CID 162232527.

- ^ "Ram Singh | Indian philosopher | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- ^ a b c Grewal, J. S. (March 2018). Master Tara Singh in Indian History: Colonialism, Nationalism, and the Politics of Sikh Identity (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199089840.

- ^ Mangat, Devinder Singh (11 February 2023). A Brief History of the Sikhs (Multidimensional Sikh Struggles). SLM Publishers. p. 300. ISBN 9789391083403.

Education being their primary goal for positive human progress, the Samaj opened its first co-educational school at Moga in 1899. The same school later on was promoted to be Dev Samaj High School. Dev Samaj Managing Council is still running same prestigious institutions in Ferozpur, Moga, Ambala, Delhi and Chandigarh.

- ^ a b Social History of Epidemics in the Colonial Punjab. Sasha. Partridge Publishing. 28 August 2014. p. 129. ISBN 9781482836226.

The Tribune reported that during the plague epidemic of 1901, there were insufficient number of huts in Hudiabad, Zaffarwal, Moga and villages of Ali Mardan and Gundial. In Moga, the residents from both the infected and uninfected localities were asked to move into the camps and thus increase the risk of spread of the infection.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Religion and Society. Vol. 38. Christian Institute for the Study of Religion and Society. 1991. p. 21.

... history of the Punjab Mission is Rev. John Hyde popularly known as praying Hyde. He came to India in 1894 and worked mainly in the area of Ferozepore and Moga. He was instrumental in starting a Punjab Prayer Union ...

- ^ Kaur, Maninder (May 2018). "The American Presbyterian Mission in Colonial Punjab: Contribution in Social and Religious Fields (1834-1930)" (PDF). Remarking an Analisation. 3 (2): 101–107.

- ^ a b c d Windel, Aaron (30 November 2021). Cooperative Rule: Community Development in Britain's Late Empire. University of California Press. p. 69. ISBN 9780520381896.

- ^ a b Harper, Irene Mason (February 1932). Pierson, Delavan Leonard (ed.). "Modern Miracles at Moga". The Missionary Review of the World. 55: 83–87.

- ^ a b c Harper, Irene Mason (October 1932). "Moga and the Better Village". Women and Missions. 9–10: 223–226.

- ^ a b Webster, John C. B. (22 December 2018). A Social History of Christianity: North-west India since 1800. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199097579.

However, the most radical experiment in rural education was the Training School for Village Teachers at Moga. Begun in 1908, it became a middle school in 1917 and added a two-year teacher's training course in 1923. William McKee introduced the 'project method' of education in 1919. Each boy was given a small plot of land to cultivate; he could sell its produce to help pay his school expenses and earn spending money. He thus had a strong incentive to learn not only improved methods of agriculture but also arithmetic and basic accounting! In addition, each class had a special project (for example, the village home, the village farm, the village bazar, etc.) around which learning for the year would be organized and through participation in which the boys acquired some additional skills, came to understand their immediate environment, and learned to work together for the common good. This approach to education was applied to religious education as well. As Irene Harper, who taught at Moga for many years, pointed out, Moga's influence was considerable, as it was seen, both inside and beyond the Punjab, as a model for educating the rural poor. Between 1922 and 1926, eighty- eight of their ninety-six candidates in the teacher training course became teachers, seventy-five in village day or boarding schools. Moga not only continued to supervise them after they graduated but also published The Village Teacher's Journal which was translated into five languages.

- ^ a b Agricultural History. Vol. 42. Agricultural History Society. 1968. pp. 30–32.

- ^ Harper, Tim (12 January 2021). Underground Asia: Global Revolutionaries and the Assault on Empire. Harvard University Press. p. 222. ISBN 9780674724617.

Much of the initial action was uncoordinated. In November 1914 there were attempts to recruit the 23rd Cavalry stationed at Lahore, and a raid took place on a treasury at Moga in which two officials were shot dead.

- ^ Prasad, Ritika (12 May 2016). Tracks of Change. Cambridge University Press. p. 247. ISBN 9781107084216.

Similarly, the Commissioner of Jullunder reported how in Ferozepore district a crowd returning from a meeting in March 1921 refused to present their tickets to the station-master when they alighted from the train at Moga. Instead, they kept shouting 'Mahatma Gandhi ki jai, ticket nahin hai' (Hail Mahatma Gandhi, we have no ticket). Responding to this, the station-master opened the platform gate, reportedly saying 'Phatak khula hai' (the gate is open).

- ^ Singh, Shweta (10 August 1923). "Interview with Anandita Pahwa, Head - CSR, Pahwa Group: "Innovation allows us to push boundaries, find creative solutions, and deliver greater value to the communities."". TheCSRUniverse. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ Harper, A. E., ed. (1944). The Moga Journal for Teachers. 24: 31.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Nevile, Pran (2006). "A Miracle Medicine and Sex Manuals". Lahore: A Sentimental Journey. Penguin Books India. pp. 14–15. ISBN 9780143061977.

- ^ Dodd, Edward Mills (1964). The Gift of the Healer: The Story of Men and Medicine in the Overseas Mission of the Church. Friendship Press. p. 94.

- ^ Gandhi, Mohandas Karamchand (1979). The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi. Vol. 75. Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 326.

- ^ 1) Singh, 2) Singh, 1) Khushwant, 2) Satindra (1966). Ghadar, 1915. R & K Publishing House. pp. 62, 64, 67–70, 72, 73, 75–77, 79, 93. ASIN B000S04SYG.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Darling, Malcolm (1934). Wisdom and Waste in the Punjab Village. Oxford University Press. p. 107.

- ^ a b c d e f Mukherjee, Mridula (22 September 2004). Peasants in India's Non-Violent Revolution: Practice and Theory. SAGE. ISBN 9780761996866.

- ^ a b c d Chatterji, Basudev (1999). Towards Freedom: Documents on the Movement for Independence in India, 1938, Part 3. Indian Council of Historical Research. pp. 3545, 3548, 3552. ISBN 9780195644494.

- ^ Jalal, Ayesha (2000). Self and Sovereignty: Individual and Community in South Asian Islam Since 1850. Psychology Press. p. 536. ISBN 9780415220774.

- ^ Madhok, Balraj (1985). Punjab Problem: the Muslim Connection. Hindu World Publications. p. 95. ISBN 9780836415193.

There were only two tehsils or sub-divisions - Moga and Taran Taran - in the whole of Punjab which had a slight Sikh majority.

- ^ a b Khan, Yasmin (1 January 2007). The Great Partition: The Making of India and Pakistan. Yale University Press. p. 107. ISBN 9780300120783.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Bajwa, K. S. “A CRITICAL APPRAISAL OF DIARY OF ANOKH SINGH ON THE PARTITION OF INDIA 1947.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, vol. 72, 2011, pp. 1337–43. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44145744. Accessed 19 Dec. 2024.

- ^ Atkins, Robert (30 December 2021). The Gurkha Diaries of Robert Atkins MC: India and Malaya 1944 - 1958. Pen and Sword Military. p. 22. ISBN 9781399091480.

This part of the Punjab was mainly Sikh, but there were many Punjabi Muslims as well. Most of these people were murdered, although they had previously been living together in the villages in harmony. Soon after I arrived I went to Moga, where there had been a massacre. There were dead and mutilated bodies all over the place which made me feel sick. However, it was a sight one soon got used to; in fact, one became completely hardened to these horrific sights - even rather callous.

- ^ Tanwar, Raghuvendra (2006). Reporting the Partition of Punjab, 1947: Press, Public, and Other Opinions. Manohar. p. 342. ISBN 9788173046742.

Heavy loss of life and property was reported from Jullundur, Gujranwala, Quetta, and Moga.

- ^ a b c Snehi, Yogesh (24 April 2019). Spatializing Popular Sufi Shrines in Punjab: Dreams, Memories, Territoriality. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780429515637.

- ^ Rural Labour Relations in India. T.J. Byres, Karin Kapadia, Jens Lerche. Routledge. 18 October 2013. p. 66. ISBN 9781135299460.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Seshagiri, Narasimhiah, ed. (2008). "Moga". Encyclopaedia of Cities and Towns in India: Punjab. Vol. 3. Gyan Publishing House. pp. 294–295. ISBN 9788121209731.

- ^ Documents of the Ninth Congress of the Communist Party of India. Communist Party publication. Vol. 9. Congress of the Communist Party of India. 1971. pp. 157, 306, 310.

- ^ Singh, Gurharpal (1994). Communism in Punjab : a study of the movement up to 1967. Delhi: Ajanta Publications. p. 245. ISBN 81-202-0403-4. OCLC 30511796.

- ^ Party Life. Vol. 23. Communist Party of India. 1987. p. 15.

The Faridkot jatha toured the Moga sub - division for four days and went through some of the worst disturbed areas

- ^ a b c d e f Kamal, Neel (5 October 2022). "Punjab: At 50, student movement seeks birthplace Moga theatre, new roles". Times of India. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- ^ Sharma, Amaninder Pal (21 February 2014). "Recalling Moga agitation, Phoolka attempts to woo leftists". The Times of India. ISSN 0971-8257. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ^ Judge, Paramjit S. (1992). Insurrection to agitation : the Naxalite Movement in Punjab. Bombay: Popular Prakashan. pp. 133–138. ISBN 81-7154-527-0. OCLC 28372585.

- ^ Basu, Jyoti (1997). Documents of the Communist Movement in India: 1989-1991. Vol. 23. Calcutta: National Book Agency. p. 53. ISBN 81-7626-000-2. OCLC 38602806.

- ^ a b Martyrdom of Shaheed Bhagat Singh. Kulwant Singh Kooner, Gurpreet Singh Sindhra. Unistar Books. 5 February 2013. p. 10. ISBN 978-9351130611.

... Punjab was in turmoil due to student's agitation known as "Moga-Regal Cinema Movement" ...

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Randhawa, Manpreet (20 February 2013). "Moga has history of going against the tide". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- ^ a b The Punjab Story. Amarjit Kaur, Lt Gen Jagjit Singh Aurora, Khushwant Singh, MV Kamanth, Shekhar Gupta, Subhash Kirpekar, Sunil Sethi, Tavleen Singh. Roli Books. 10 August 2012.

His [Bhindranwale's] favourite story, for example, of atrocities committed upon Sikhs by Hindus was the instance of a village near Moga where the Hindus had ganged up against a Sikh girl. 'She was harassed and then beaten; he said, 'and then in full public view stripped naked. As if that was not enough, they (the Hindus) forced her father to have intercourse with her.' I heard him tell this story at least three times. ... But when asked to furnish details of the name of the family, village, etc., Bhindranwale turned evasive and belligerent.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Amritsar: Mrs Gandhi's Last Battle. Mark Tully, Satish Jacob. J. Cape. 1985. p. 140. ISBN 9780224023283.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Joshi, Chand (1984). Bhindranwale: Myth and Reality. Vikas. pp. 24, 28. ISBN 9780706926941.

- ^ a b Bhattacharya, Samir (2014). NOTHING BUT!. Vol. 4: Love Has No Religion. Partridge Publishing. p. 568. ISBN 9781482817201.

A month earlier on getting the news that some militants had taken refuge inside the gurdwara at Moga, near Ludhiana, the government had ordered the paramilitary batallion from the BSF, the Border Security Force to lay a siege to it and not to lift it under any circumstances till the militants surrendered. But after five days into the siege when the high priests of the Golden Temple threatened that they would lead a march on Moga if the siege was not lifted, the government it seems meekly caved in. They feared that the siege would only fuel the fire in the countryside and they could not afford to antagonize the common people anymore.

- ^ a b Weintraub, Richard M. (26 June 1989). "SIKH MILITANTS FIRE ON HINDU GATHERING IN PUNJAB". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ^ Pettigrew, Joyce (27 April 1995). The Sikhs of the Punjab: Unheard Voices of State and Guerilla Violence. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 18–20. ISBN 9781856493550.

- ^ a b "Punjab Govt, police official told to pay Rs 2.50 lakh relief". The Tribune. 5 August 2003. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- ^ ""Panth in danger" – Badal's politics shifts back from Chandigarh to Amritsar". Times of India Blog. 28 July 2014. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- ^ Singh, Kuldip (31 October 2024). Punjab River Waters Dispute in South Asia: Historical Legacies, Political Competition, and Peasant Interests. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781040273753.

The tendencies toward moderation were clearly visible toward the end of 1994 when the Akal Takht Jathedar issued directive to various Akali factions to merge into one party. The Badal faction decided to remain away because the other Akali factions, which eventually merged into Akali Dal Amritsar clearly had a secessionist agenda. From then on, the Akali Dal Badal was on a new path of moderate politics, which could also be read through its Moga Declaration of 1996.

- ^ Sullivan, Bruce M. (22 October 2015). "Sikh Museuming". Sacred Objects in Secular Spaces: Exhibiting Asian Religions in Museums. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 62. ISBN 9781472590831.

There is controversy associated with relics that travel; the Shiromani Gurdwara Prabhandak Committee (SGPC), which governs Sikh gurdwaras in Punjab and is both religiously and politically powerful, planned to reprimand and demand penance from Gursewak Singh Sodhi of Dhilwana Kalan village, in the Moga district of the Indian Punjab, for sending relics consisting of the clothes and turban of Guru Gobind Singh to Canada from a shrine there without its permission in 2003. The SGPC claimed that this had "really hurt" the sentiments of India's Sikh community ...

- ^ "Farmers' agitation: 150 held in Moga". Hindustan Times. 10 March 2013. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ^ "Farmers' agitation: Back from Tikri border, Moga man dies of illness". The Tribune, India. Tribune News Service. 13 April 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Ramakrishnan, Venkitesh (30 December 2020). "Farmers in Punjab stand in for those involved in the Delhi agitation by fulfilling their farming roles". Frontline - The Hindu (frontline.thehindu.com). Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ^ Jaglan, Mahabir S. (30 September 2024). "6: Protest-landscape of the farmers' movement in Haryana". In Singh, Shamsher; Siddiqui, Sabah (eds.). A People's History of the Farmers' Movement, 2020–2021. Rajeshwari. Taylor & Francis. pp. 84–106. doi:10.4324/9781003496625-6. ISBN 9781040122679.

It was here in Moga the seeds of the forthcoming pan-India farmers' agitation were sown when 32 farmer unions decided to begin a collective struggle against the new farm laws (Times News Network, 2021). They carried out an about two-month agitation in Punjab between September and November 2020.

- ^ a b c Prill, Susan E. (27 March 2014). "19. Ecotheology". In Singh, Pashaura; Fenech, Louis E. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. pp. 223–234. ISBN 9780191004117.

- ^ "Indian police have arrested a Sikh separatist leader who had been on the run". National Public Radio (NPR). The Associated Press. 23 April 2023. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Sharma, B.R. (1983). "Preface". Punjab District Gazetteers - Firozpur District. Revenue Department of Punjab.

- ^ Singh, Karan (12 May 2023). "Baba Lakhdata/Pir Nigaha/Shakhi Sarwar". Syncretic Shrines and Pilgrimages: Dynamics of Indian Nationalism. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781000880038.

Baba Lakhdata/Pir Nigaha/Shakhi Sarwar has two shrines in India: In village Langiana, district Moga, Punjab, and village Basoli, district Una, Himachal Pradesh.

- ^ Chaudhuri, Supriya (19 August 2021). "Memorializing Sakhi Sarwar, Baba Farid, and Sabir Pak". Religion and the City in India. Routledge. ISBN 9781000429015.

Post-Partition, two important Sakhi Sarwar shrines (Nigaha) are located in Una in Himachal Pradesh and Moga in Indian Punjab.

- ^ Singh, Joginder (22 August 2017). "Dhuna of Baba Sri Chand Korewal (Moga)". Religious Pluralism in Punjab: A Contemporary Account of Sikh Sants, Babas, Gurus and Satgurus. Routledge. ISBN 9781351986342.

- ^ Decadal Variation In Population Since 1901

- ^ a b c d e f "District Census Hand Book – Moga" (PDF). Census of India. Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India.

- ^ US Directorate of Intelligence. "Country Comparison:Population". Archived from the original on 13 June 2007. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

Fiji 883,125 July 2011 est.

- ^ "2010 Resident Population Data". U. S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 27 December 2010. Retrieved 30 September 2011.

Montana 989,415

- ^ "District-wise Decadal Sex ratio in Punjab". Open Government Data (OGD) Platform India. 21 January 2022. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ^ "Open Government Data (OGD) Platform India". 21 January 2022.

- ^ a b "Table C-16 Population by Mother Tongue: Punjab". censusindia.gov.in. Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India.

- ^ "Table C-01 Population by Religious Community: Punjab". censusindia.gov.in. Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India.

- ^ a b "Open Government Data (OGD) Platform India - All Religions". data.gov.in. 21 January 2022. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ "District-wise Income of Municipalities/Corporations in Punjab from Municipal Rates and Taxes in Punjab from 1968 to 2018 (As on March)". 8 July 2020. Retrieved 1 October 2024.

- ^ Biswas, Asit K.; Tortajada, Cecilia; Joshi, Yugal K.; Gupta, Aishvarya. Creating Shared Value: Impacts of Nestlé's Moga Factory on Surrounding Area - Executive Summary, 2012 (PDF). Third World Centre for Water Management, Mexico. p. 6.

- ^ "Brief Industrial Profile of Moga District", MSME Development Institute, Government of India, Ministry of MSME, Table 3.2, https://dcmsme.gov.in/old/dips/Moga.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwiDqdnfuvCFAxWhzzgGHaRrCq0QFnoECCcQAQ&usg=AOvVaw03mOj6UIHAuTYhERPXwiPV

- ^ a b c d "Moga's special place in Punjab politics, and why Akalis are planning their SYL show there". Hindustan Times. Indo-Asian News Service. 9 December 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "In agri-rich Punjab, a fight to reclaim forest cover". The Times of India. 22 August 2022. ISSN 0971-8257. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ a b Singh, Harmandeep (9 June 2021). "Forest cover in Punjab's Moga to go up to 5% in 5 years". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ Sandhu, Kulwinder (23 September 2021). "Garden with trees mentioned in Guru Granth Sahib opened in Moga". The Tribune (India).

- ^ a b https://www.niti.gov.in/sites/default/files/2022-07/Moga-Punjab.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "National Family Health Survey - 5 2019 -21, District Fact Sheet, Moga, Punjab", http://rchiips.org/nfhs/NFHS-5_FCTS/PB/Moga.pdf

- ^ "National Family Health Survey - 4 2015 -16, District Fact Sheet, Moga, Punjab", Page 2, http://rchiips.org/NFHS/FCTS/PB/PB_FactSheet_42_Moga.pdf

- ^ "Road Accidents in Punjab". punjab.data.gov.in. Retrieved 1 October 2024.

- ^ "List of Deputy Commissioners". Moga. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

External links

edit- Official website

- DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK - MOGA DISTRICT Archived 17 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Human Development in Punjab