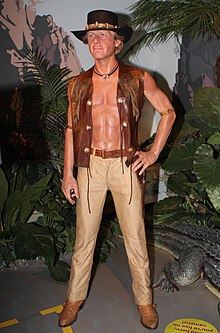

Michael J. "Crocodile" Dundee (also called Mick), played by Paul Hogan, is a fictional protagonist in the Crocodile Dundee film series consisting of Crocodile Dundee, Crocodile Dundee II, and Crocodile Dundee in Los Angeles.[2] The character is a crocodile hunter, hence the nickname[3] and is modeled on Rod Ansell.[4]

| Michael "Crocodile" Dundee | |

|---|---|

| Crocodile Dundee character | |

Michael "Crocodile" Dundee | |

| First appearance | Crocodile Dundee (1986) |

| Last appearance | Dundee: The Son of a Legend Returns Home |

| Created by | Paul Hogan |

| Portrayed by | Paul Hogan[1] |

| In-universe information | |

| Full name | Michael J. Dundee |

| Nickname | Mick Crocodile Dundee |

| Occupation | Crocodile hunter |

| Spouse | Sue Charlton (second wife) |

| Relatives | Michael "Mikey" Dundee (son) Brian Dundee (other son) |

| Nationality | Australian |

Paul Hogan on the Dundee character

editIn TV Week magazine, Paul Hogan spoke of the character:

Mick's a good role model. There's no malice in the fellow and he's human. He's not a wimp or a sissy just because he doesn't kill people.[5]

He said the character was seen by people in the US as a cross between Chuck Norris and Rambo. This did not sit well with Hogan, who said people would rather see his character "who doesn't kill 75 people" than the likes of "those commandos, terminators, ex-terminators and squashers".[5]

Character biography

editDundee was supposedly born in a cave, in the Northern Territory, and raised by Indigenous Australians. He is unaware of his age; he once asked an Aboriginal elder when he was born, the reply was "in the summertime". Until the events of the first film, Dundee said he had never lived in a city, or even been to one ("Cities are crowded, right? If I went and lived in some city, I'd only make it worse").[6] He owns a piece of land called "Billongamick" ("belong to Mick"), meaning "Mick's place", that he inherited from an uncle. He estimates that a person might walk across it in three to four days, but he regards it as useless except for a gold mine that he refers to as "the Reserve Bank" and his "retirement fund". Dundee is rarely seen without his black Akubra hat or his Bowie knife.

Crocodile Dundee

editDuring the first film, Crocodile Dundee, Mick is visited by a New York reporter, Sue Charlton, who travels to Australia to investigate a report she heard of a crocodile hunter who had his leg bitten off by a crocodile in the outback, but made it the supposedly hundred or so miles back to civilization and lived. However, by the time she meets him, the story turns out to be a somewhat exaggerated legend where the "bitten off leg" turns out to be just being some bad scarring on his leg; a "love bite" as Mick calls it. Still intrigued by the idea of "Crocodile" Dundee, Sue continues with the story. They travel together out to where the incident occurred, and follow his route through the bush to the nearest hospital. Despite his macho approach and seemingly sexist opinions, the pair eventually become close, especially after Mick saves Sue from a crocodile attack. Feeling there is still more to the story, Sue invites Mick back to New York with her, as his first trip to a city (or "first trip anywhere", as Dundee says). The rest of the film depicts Dundee as a "fish out of water", showing how despite his expert approach to the bush, he knows little of city life. Mick meets Sue's fiancé, Richard, who work together and have a lot in common, but they do not get along. By the end of the film, Mick is on his way home, lovesick, when Sue realizes she loves Mick, not Richard. She runs to the subway station to stop Mick from leaving and, by passing on messages through the packed to the gills crowd, she tells him she will not marry Richard, and she loves him instead. With the help of the other people in the subway, Mick and Sue have a loving reunion as the film ends.

Crocodile Dundee II

editBy the second film, Crocodile Dundee II, Mick and Sue are living together in a New York apartment. Sue's ex-husband is in Colombia following a gang of drug dealers; he posts some evidence to Sue, as she is the only person he can trust. When he is discovered and killed by the dealers, they realize he has sent information to Sue, and kidnap her to get it back. Mick, who only receives the letter that morning, does not realize that Sue is in trouble until she phones from the kidnapper's house. With help from a local gang, Mick breaks in and sneaks Sue out. Mick and Sue head to Australia for protection. The Colombians follow and try to track Mick and Sue, but Mick is always one step ahead.[7]

Crocodile Dundee in Los Angeles

editThe third movie, Crocodile Dundee in Los Angeles, is set around 13 years later. Mick is living with Sue and their 9-year-old son Mikey. Now that it is illegal to kill saltwater crocodiles in Australia, Mick is forced to relocate and wrestle crocodiles. Sue replaces a worker at her father's newspaper who died mysteriously, so Mick and Mikey travel with Sue to Los Angeles while she fills the position until a full replacement is found. Together they travel around Los Angeles and the usual fish-out-of-water jokes occur. Mick uses his detective skills to discover that a film crew had been smuggling paintings that had supposedly been destroyed years earlier (during the Yugoslav Wars), and that they have killed a reporter for getting too close to the truth. The guilty members of the crew are arrested, and Mick and Sue then finally get married back in Australia.

Status as an Australian icon

editDue to the popularity of the character outside of Australia, Crocodile Dundee has become something of an icon of Australia.[8][9][10] He appeared in commercials for the Subaru Outback which, although a Japanese car, was given an Australian image to suggest its toughness and ability to compete with other sport-utility vehicles.[11] He also appeared in the closing ceremony of the 2000 Summer Olympics.[12][13] The character has been used in Tourism ads.[14]

References

edit- ^ Harmetz, Aljean (12 January 1987). "THE CROSSOVER APPEAL OF 'CROCODILE'". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 August 2010.

- ^ "Crocodile Dundee, 1985: 'You can't take my photograph'". FUSE. Department of Education and Training. 19 March 2019.

- ^ Darnton, Nina (26 September 1986). "FILM: 'CROCODILE DUNDEE'". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 August 2010.

- ^ Milliken, Robert (12 August 1999). "Obituary: Rod Ansell". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 12 May 2022. Retrieved 15 March 2012.

- ^ a b Davies, Ivor (4 June 1988). "Box office war". TV Week. Are Media. p. 11.

- ^ O'Regan, Tom (2 April 2015). ""Fair Dinkum Fillums": the Crocodile Dundee Phenomenon". Culture & Communications Reading Room. Murdoch University. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (25 May 1988). "Crocodile Dundee 2 (1988) / Paul Hogan Is Back to His Tricks". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 August 2010.

- ^ Bloomfield, Amelia (6 October 1993). "Sydney Olympics 2000: Beyond Crocodile Dundee". Corsair. Santa Monica, California.

- ^ Cernetig, Miro (14 September 2000). "Forget Crocodile Dundee, Aussies plead". The Globe and Mail. The Woodbridge Company.

- ^ Harmetz, Aljean (14 October 1986). "THE IMPORTING OF 'CROCODILE DUNDEE'". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 August 2010.

- ^ Serafin, Raymond (18 September 1995). "SUBARU OUTBACK TAPS 'CROCODILE DUNDEE'". Ad Age. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- ^ "Sydney 2000 Olympics: Closing Ceremony". The Sydney Morning Herald. 13 August 2020. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ "Sydney goes out with a bang!". Olympics.com. 30 September 2020. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ "Crocodile Dundee inspires new American tourism push". Tourism Australia. 5 February 2018.