Maranhão (Brazilian Portuguese pronunciation: [maɾɐˈɲɐ̃w] ) is a state in Brazil. Located in the country's Northeast Region, it has a population of about 7 million and an area of 332,000 km2 (128,000 sq mi). Clockwise from north, it borders on the Atlantic Ocean for 2,243 km and the states of Piauí, Tocantins and Pará. The people of Maranhão have a distinctive accent within the common Northeastern Brazilian dialect. Maranhão is described in literary works such as Exile Song by Gonçalves Dias and Casa de Pensão by Aluísio Azevedo.

Maranhão | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Anthem: Hino do Maranhão | |

Location of State of Maranhão in Brazil | |

| Coordinates: 6°11′S 45°37′W / 6.183°S 45.617°W | |

| Country | |

| Founded | 1621 |

| Capital and largest city | São Luís |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Carlos Brandão (PSB) |

| • Vice Governor | Felipe Camarão (PT) |

| • Senators | Ana Paula Lobato (PDT) Eliziane Gama (PSD) Weverton Rocha (PDT) |

| Area | |

• Total | 331,983.293 km2 (128,179.466 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 8th |

| Population (2022)[1] | |

• Total | 6,776,699 |

| • Rank | 10th |

| • Density | 20/km2 (53/sq mi) |

| • Rank | 16th |

| Demonym | Maranhense |

| GDP | |

| • Total | R$ 124.981 billion (US$ 23.184 billion) |

| HDI | |

| • Year | 2021 |

| • Category | 0.676[3] – medium (27th) |

| Time zone | UTC-3 (BRT) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-2 (BRST) |

| Postal Code | 65000-000 to 65990-000 |

| ISO 3166 code | BR-MA |

| License Plate Letter Sequence | HOL to HQE, NHA to NHT, NMP to NNI, NWS to NXQ, OIR to OJQ, OXQ to OXZ, PSA to PTZ, ROA to ROZ, SMM to SNJ |

| Website | ma.gov.br |

The dunes of Lençóis are an important area of environmental preservation. Also of interest is the state capital of São Luís, which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Another important conservation area is the Parnaíba River delta, between the states of Maranhão and Piauí, with its lagoons, desert dunes and deserted beaches or islands, such as Caju island, which shelters rare birds.

Geography

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2021) |

The northern portion of the state is a heavily forested plain traversed by numerous rivers, occupied by the eastern extension of the tropical moist forests of Amazonia. The Tocantins–Araguaia–Maranhão moist forests occupy the northwestern portion of the state, extending from the Pindaré River west into neighboring Pará state. The north-central and northeastern portion of the state, extending eastward into northern Piauí, is home to the Maranhão Babaçu forests, a tropical moist forest ecoregion dominated by the Babaçu palm. The Babaçu palm produces oil which is extracted commercially and used for a variety of purposes including food and beauty products.[4][5][6]

The southern portion of the state belong to the lower terraces of the great Brazilian Highlands, occupied by the Cerrado savannas. Several plateau escarpments, including the Chapada das Mangabeiras, Serra do Tiracambu, and Serra das Alpercatas, mark the state's northern margin and the outlines of river valleys.

The climate is hot, and the year is divided into a wet and dry season. Extreme humidity characterizes the wet season. The heat, however, is greatly modified on the coast by the south-east trade winds.

The rivers of the state all flow northward to the Atlantic and a majority have navigable channels. The Gurupí River forms the northwestern boundary of the state, separating Maranhão from neighboring Pará. The Tocantins River forms part the state's southwestern boundary with Tocantins state. The Parnaíba River forms the eastern boundary of Maranhão, but it has one large tributary, the Balsas, entirely within the state. Other rivers in the state include the Turiassu (or Turiaçu) which runs just east of the Gurupi, emptying into the Baía de Turiassu; the Mearim, Pindaré, and Grajaú, which empty into the Baía de São Marcos; and the Itapecuru and Munim which discharge into the Baía de São José. Like the Amazon, the Mearim has a pororoca or tidal bore in its lower channel, which greatly interferes with navigation.

The western coastline has many small indentations, which are usually masked by islands or shoals. The largest of these are the Baía de Turiassu, facing which is São João Island, and the contiguous bays of São Marcos and São José, between which is the large island of São Luís. This indented shoreline is home to the Maranhão mangroves, the tallest mangrove forests in the world. The coastline east of Baía de São José is less indented and characterized by sand dunes, including the stark dune fields of the Lençóis Maranhenses National Park, as well as restinga forests that form on stabilized dunes.

Highest point

editChapada das Mangabeiras 804 m, at 10º 15' 45" S, 46º 00' 15" W.

History

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2021) |

The etymology of Maranhão is uncertain; the name probably originates from Portuguese settlers from Maranhão in Avis in the province of Alentejo. The word was first used to refer to the Amazon River, which is today used to refer to the Peruvian part of the river (Marañón).

The first known European to explore Maranhão was the Spanish explorer Vicente Yáñez Pinzón in 1500[citation needed], but it was granted to João de Barros in 1534 as a Portuguese hereditary captaincy. The first European settlement, however, was made by a French trading expedition under Jacques Riffault, of Dieppe,[7] in 1594, who lost two of his three vessels in the vicinity of São Luís Island, and left a part of his men on that island when he returned home. Subsequently, Daniel de La Touche, Seigneur de La Rividière was sent to report on the place, and was then commissioned by the French crown to found a colony on the island (Equinoctial France); this was done in 1612. The French were expelled by the Portuguese in 1615, and the Dutch held the island from 1641 to 1644. In 1621 Ceará, Maranhão and Pará were united and called the "Estado do Maranhao", which was separated from the southern captaincies. Very successful Indian missions were soon begun by the Jesuits, who were temporarily expelled as a result of a civil war in 1684 for their opposition to the enslavement of the Indians. Ceará was subsequently detached, but the State of Maranhão remained separate until 1774, when it again became subject to the colonial administration of Brazil.

In the late 18th century, there was a great influx of enslaved peoples into the region, which corresponded to the increased cultivation of cotton. According to the historian Sven Beckert, the region's cotton exports "doubled between 1770 and 1780, nearly doubled again by 1790, and nearly tripled once more by 1800."[8]

Maranhão did not join in the Brazilian declaration of independence of 1822, but in the following year the Portuguese were driven out by British sailor and liberator Admiral Lord Cochrane and it became part of the Empire of Brazil. For this achievement Lord Cochrane became 1st Marques of Maranhão and Governor of Maranhão Province.

São Luís is the Brazilian state capital which most closely resembles a Portuguese city. By the early 20th century São Luís had about 30,000 inhabitants, and contained several convents, charitable institutes, the episcopal palace, a fine Carmelite church, and an ecclesiastical seminary. The historic city center was declared a World Heritage Site in 1997.

Demographics

editAccording to the IBGE, there were 6,776,699 people residing in the state in 2022. The population density was 20.6 inhabitants/km2.

Urbanization: 68.1% (2004); Population growth: 1.5% (1991–2000); Houses: 1,442,500 (2005).[9]

The last PNAD (National Research for Sample of Domiciles) census revealed the following numbers: 4,499,018 Brown (Multiracial) people (66.4%), 1,361,865 White people (20.1%), 854,424 Black people (12.6%), 54,682 Amerindian people (0.8%), 6,541 Asian people (0.1%).[10]

According to a DNA study from 2005, the average ancestral composition of São Luís, the biggest city in Maranhão, is 42% European, 39% native American and 19% African.[11]

Largest cities

editLargest cities or towns in {{{country}}}

(2011 census by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics)[12] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Microregion | Pop. | Rank | Microregion | Pop. | ||||

| São Luís Imperatriz |

1 | São Luís | São Luís | 1,027,429 | 11 | Balsas | Gerais de Balsas | 85,321 | |

| 2 | Imperatriz | Imperatriz | 248,805 | 12 | Barra do Corda | Alto Mearim e Grajaú | 83,582 | ||

| 3 | Timon | Caxias | 156,327 | 13 | Pinheiro | Baixada Maranhense | 78,875 | ||

| 4 | Caxias | Caxias | 156,327 | 14 | Santa Luzia | Pindaré | 74,500 | ||

| 5 | São José de Ribamar | São Luís | 165,418 | 15 | Chapadinha | Chapadinha | 74,273 | ||

| 6 | Codó | Codó | 118,567 | 16 | Buriticupu | Pindaré | 66,325 | ||

| 7 | Paço do Lumiar | São Luís | 107,764 | 17 | Coroatá | Microrregião de Codó | 62,189 | ||

| 8 | Açailândia | Imperatriz | 105,254 | 18 | Itapecuru-Mirim | Itapecuru-Mirim | 63,023 | ||

| 9 | Bacabal | Médio Mearim | 100,614 | 19 | Grajaú | Alto Mearim e Grajaú | 63,203 | ||

| 10 | Santa Inês | Pindaré | 78,020 | 20 | Barreirinhas | Lençois Maranhenses | 56,123 | ||

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1872 | 359,040 | — |

| 1890 | 430,854 | +20.0% |

| 1900 | 499,308 | +15.9% |

| 1920 | 874,337 | +75.1% |

| 1940 | 1,235,169 | +41.3% |

| 1950 | 1,583,248 | +28.2% |

| 1960 | 2,492,139 | +57.4% |

| 1970 | 3,037,135 | +21.9% |

| 1980 | 4,097,231 | +34.9% |

| 1991 | 4,929,029 | +20.3% |

| 2000 | 5,657,552 | +14.8% |

| 2010 | 6,574,789 | +16.2% |

| 2022 | 6,776,699 | +3.1% |

| Source:[1] | ||

Religion

editReligion in Maranhão (2010)

According to the 2010 Brazilian Census, most of the population (74.5%) is Roman Catholic, other religious groups include Protestants or evangelicals (17.2%), Spiritists (0.2%), Nones 6.3%, and people with other religions (1.8).[13][14]

Education

editPortuguese is the official national language, and thus the primary language taught in schools. English and Spanish are part of the official high school curriculum.

Educational institutions

editEducational institutions in Maranhão include:

- Universidade Federal do Maranhão (UFMA) (Federal University of Maranhão)

- Universidade Estadual do Maranhão (UEMA) (State University of Maranhão)

- Universidade Estadual da Região Tocantina do Maranhão (UEMASUL) (State University of the Tocantina Region of Maranhão)

- Centro Universitário do Maranhão (UNICEUMA) (University Center of Maranhão)

- Unidade de Ensino Superior do Sul do Maranhão (UNISULMA)

- Unidade de Ensino Superior Dom Bosco (UNDB)

- Instituto Federal do Maranhão (IFMA)

- Instituto Estadual do Maranhão (IEMA)

- Instituto de Teologia Logos (ITL) (Logos Institute of Theology)

- Colégio Militar Tiradentes (CMT)

Economy

editMaranhão is one of the poorest states of Brazil.[15] The state has 3.4% of the Brazilian population and produces only 1.3% of the Brazilian GDP.

The service sector is the largest component of GDP at 70%, followed by the industrial sector at 19.6%. Agriculture represents 10.4% of GDP (2015). Maranhão is the fourth-largest economy in the Northeast region and the 17th-largest in Brazil.[citation needed]

Maranhão exports: aluminium 50%, iron 23.7%, soybean 13.1% (2002). Share of the Brazilian economy: 0.9% (2004).[16]

Maranhão is also known as the land of the palm trees, as the various species of this tree provide its major source of income. The most important of them, from an economic point of view, is the babassu. Agribusiness, the aluminium and alumina transformation industries, the pulp industry, natural gas production, and the food and timber industries complement the state economy.[citation needed]

The Maranhão agricultural sector stands out in the production of rice (fifth-largest rice production in the country, and highest in the Northeast), cassava (second-largest planted area in the Northeast), soybean, cotton (in both cases second-largest producer in the Northeast), sugarcane, corn and eucalyptus. Agriculture benefits from the infrastructure of railroads (Ferrovia Carajás and Ferrovia Norte-Sul) and ports (Itaqui and Ponta da Madeira) and the proximity to the European and American markets.[17]

Maranhão has the second largest cattle herd in the Northeast and the 12th largest in the country, with 7.6 million animals.[18]

The state also produces natural gas in the Parnaíba basin, with a production of 8.4 million m3 per day, used in thermal power stations. Maranhão is the 6th largest producer in the country. Maranhão also has a hydroelectric plant (Estreito Hydroelectric Plant), a wind farm (in Lençóis Maranhenses), and a thermoelectric plant (Suzano Maranhão Thermal Power Plant).[19]

Itaqui Port annually moves millions of tons of cargo, being an important logistics corridor for the Center-West of the country. It is the second deepest port in the world. Among the main products handled in 2017 are soybeans (6,152,909 tons), corn (1,642,944 tons), fertilizers (1,536,697 tons), copper (836,062 tons), coal (636,254 tons), pig iron (505,733 t) clinker + slag (225,796 t), manganese (147,063 t), rice (89,833 t), imported liquid bulk (3,881,635 t), caustic soda (86,542 t), ethanol and LPG (150,753 t), totaling an annual turnover of 17,140,470 tons.[20]

The port of Ponta da Madeira, belonging to the Vale do Rio Doce is mainly destined for the export of iron ore brought from the Serra dos Carajás, in Pará. Between January and November 2017, 153.466 million tons were transported, and it is the national champion in moving loads. The Alumar Consortium Port transported 13.720 million tons between January and November 2017, mainly alumina.[21]

Infrastructure

editAirports

editMarechal Cunha Machado International Airport is located 13 kilometres (8.1 mi) from the center of São Luís. It began handling international flights in October 2004. It has a covered area of 8,100 square metres (87,000 sq ft) and a capacity of one million passengers per year.[citation needed]

Renato Moreira Airport is a national airport located in Imperatriz. Infraero has administered the airport since November 3, 1980, one year before it was officially opened. The passenger terminal was modified and expanded in 1998, giving it new arrival and departure areas, an expanded main concourse, and air conditioning of the entire terminal.[citation needed]

Highways

editThe main highways in Maranhão are BR-010, BR-135, BR-316, BR-222 and BR-226. The state has a weak road infrastructure in the southern part of the state, and was identified, in 2022, as one of the worst road networks in the country.[22][23]

Railroads

editFerrovia Carajás

Ferrovia Norte-Sul

Ferrovia São Luís-Teresina

Telecommunications

editThe telephone area codes (named DDD in Brazil) for Maranhão are 98 and 99.[24]

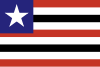

Flag

editThe flag of Maranhão was designed by the poet Joaquim de Souza Andrade, and was adopted by decree nr. 6, of December 21, 1889.[citation needed]

The colored strips (red, white and black) symbolize the different ethnic groups which make up the population, and their mixing and living together. The white star in the upper left corner symbolizes Maranhão itself, and is supposed to be Beta Scorpii, as the constellation Scorpius is also depicted on the national flag of Brazil. The flag has a ratio of 2:3.[citation needed]

Portrayals in film

edit- Andrucha Waddington's The House of Sand (Casa de Areia, 2005) prominently features the sand dunes of Maranhão.

- Carla Camurati's Carlota Joaquina, Princess of Brazil (1995) was filmed in the historical center of São Luís, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- The song "Kadhal Anukkal" from the film Endhiran (Tamil, 2010) featuring Aishwarya Rai and Rajnikanth was filmed at the Lençóis Maranhenses National Park sand dunes.

References

edit- ^ a b "2022 Census Overview" (in Portuguese).

- ^ "PIB por Unidade da Federação, 2021". ibge.gov.br.

- ^ "Atlas do Desenvolvimento Humano no Brasil. Pnud Brasil, Ipea e FJP, 2022". www.atlasbrasil.org.br. Retrieved 2023-06-11.

- ^ Quebradeiras de coco babaçu do Maranhão são destaque na I Feira Nordestina da Agricultura Familiar e Economia Solidária no RN

- ^ "The Brazilian women facing violence and sexual harassment on farms". The Independent. 2019-10-21. Retrieved 2024-08-20.

- ^ Puppim de Oliveira, José A.; Mukhi, Umesh; Quental, Camilla; de Oliveira Cerqueira Fortes, Paulo Jordão (2022). "Connecting businesses and biodiversity conservation through community organizing: The case of babassu breaker women in Brazil". Business Strategy and the Environment. 31 (5): 2618–2634. doi:10.1002/bse.3134. ISSN 0964-4733.

- ^ Faure, Michel (25 February 2016). Une Histoire du Brésil. edi8. p. 72. ISBN 978-2-262-06631-4. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ Beckert, Sven (2014). Empire of Cotton: A Global History. New York: Knopf.

- ^ Source: PNAD.

- ^ "Censo 2022 - Panorama".

- ^ Ferreira, Francileide Lisboa; Leal-Mesquita, Emygdia Rosa; Santos, Sidney Emanuel Batista dos; Ribeiro-dos-Santos, Ândrea Kely Campos (March 2005). "Genetic characterization of the population of São Luís, MA, Brazil". Genetics and Molecular Biology. 28 (1): 22–31. doi:10.1590/S1415-47572005000100004.

- ^ "Estimativas da população residente nos municípios brasileiros com data de referência em 1º de julho de 2011" [Estimates of the Resident Population of Brazilian Municipalities as of July 1, 2011] (PDF) (in Portuguese). Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. 30 August 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

- ^ Censo 2010

- ^ «Análise dos Resultados/IBGE Censo Demográfico 2010: Características gerais da população, religião e pessoas com deficiência»

- ^ "Piauí deixa de ser Estado mais pobre do Brasil, aponta a FGV | Ai5Piauí - Notícias do Piauí". Archived from the original on 2010-03-17. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

- ^ List of Brazilian states by GDP (in Portuguese). Maranhão, Brazil: IBGE. 2004. ISBN 85-240-3919-1.

- ^ "Agriculture of Maranhão" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-07-13. Retrieved 2018-05-05.

- ^ "Maranhão conquista o maior índice vacinal contra febre aftosa do..." Maranhão de Todos Nós (in Brazilian Portuguese). 2016-08-02. Archived from the original on 2018-03-24. Retrieved 2018-05-05.

- ^ "Gasmar | Governo do Estado do Maranhão". www.ma.gov.br (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 2018-05-05.

- ^ Redação. "Portos e Navios - Itaqui movimenta 16,3 milhões de toneladas de janeiro a outubro" (in Brazilian Portuguese). Archived from the original on 2018-02-05. Retrieved 2018-05-05.

- ^ Redação. "Portos e Navios - Itaqui movimenta 16,3 milhões de toneladas de janeiro a outubro" (in Brazilian Portuguese). Archived from the original on 2018-02-05. Retrieved 2018-05-05.

- ^ Maranhão road map

- ^ Maranhão apresenta a pior malha de rodovias federais da região Nordeste, aponta pesquisa da CNT

- ^ "DDD do Maranhao". Retrieved August 12, 2016.

References

edit- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Maranhão". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 668.

This article incorporates text from the Catholic Encyclopedia, a publication now in the public domain.

External links

edit- Freguesia de Maranhão em Portugal - https://pt.wiki.x.io/wiki/Maranh%C3%A3o_(Avis)

- Official website Archived 2021-08-20 at the Wayback Machine (in Portuguese)

- Relação Sumária das Cousas do Maranhão, by Simão Estácio da Silveira Archived 2015-10-05 at the Wayback Machine, a contemporary account of the early Portuguese colonization of Maranhão, published in Lisbon in 1624 by a leading coloniser (in Portuguese)

- History of the Commerce of Maranhão (1612 - 1895), by Jerônimo de Viveiros (in Portuguese) (PDF)

- Revista do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro, 1909, Tomo LXXII - Parte I, Chronicle of the Jesuits in Maranhão, by João Felipe Bettendorf (in Portuguese) (PDF)

- Historical geographical dictionary of Maranhão, by César Marques (in Portuguese)