The Mantra-Rock Dance was a counterculture music event held on January 29, 1967, at the Avalon Ballroom in San Francisco.[1] It was organized by followers of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON) as an opportunity for its founder, A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, to address a wider public.[2] It was also a promotional and fundraising effort for their first center on the West Coast of the United States.[3][4]

The Mantra-Rock Dance featured some of the most prominent Californian rock groups of the time, such as the Grateful Dead[5][6] and Big Brother and the Holding Company with Janis Joplin,[7] as well as the then relatively unknown Moby Grape.[8][9] The bands agreed to appear with Prabhupada and to perform for free; the proceeds were donated to the local Hare Krishna temple.[3] The participation of countercultural leaders considerably boosted the event's popularity; among them were the poet Allen Ginsberg, who led the singing of the Hare Krishna mantra onstage along with Prabhupada, and the LSD promoters Timothy Leary and Augustus Owsley Stanley III.[3][10]

According to author Margaret Wilkins, the Mantra-Rock Dance concert was "the ultimate high"[4][11] and "the major spiritual event of the San Francisco hippie era."[3] It led to favorable media exposures for Prabhupada and his followers,[12] and brought the Hare Krishna movement to the wider attention of the American public.[10] The 40th anniversary of the Mantra-Rock Dance was commemorated in 2007 in Berkeley, California.[13]

Background

editA. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada (also referred to as "Bhaktivedanta Swami" or "Prabhupada"), a Gaudiya Vaishnava sannyasi and teacher, arrived in New York City from his native India in 1965 and "caught the powerful rising tide" of a counterculture that was fascinated with his homeland and open to new forms of "consciousness-expanding spirituality."[14] After establishing his first American temple in New York City at 26 Second Avenue, Prabhupada requested his early follower Mukunda Das[15][nb 1] and his wife Janaki Dasi to open a similar ISKCON center on the West Coast of the United States.[16][17][18]

Mukunda and Janaki met up with friends from college, who would later come to be known as Shyamasundar Das, Gurudas, Malati Dasi, and Yamuna Dasi. Teaming up with them, Mukunda rented a storefront in the San Francisco Haight-Ashbury neighborhood,[19][20] which at that time was turning into the hub of the hippie counterculture, and stayed to take care of the developing new center.[16][21]

Preparation and promotion

editTo raise funds, gain supporters for the new temple, and to popularize Prabhupada's teachings among the hippie and countercultural audience of the Haight-Ashbury scene, the team decided to hold a charitable rock concert and invited Prabhupada to attend.[4] Despite his position as a Vaishnava sannyasi and some of his New York followers objecting to what they saw as an inappropriate invitation of their guru to a place full of "amplified guitars, pounding drums, wild light shows, and hundreds of drugged hippies,"[22] Prabhupada agreed to travel from New York to San Francisco and take part in the event.[10][nb 2] Using their acquaintance with Rock Scully, manager of the Grateful Dead, and Sam Andrew, founding member and guitarist of the Big Brother and the Holding Company – who were among the most prominent rock bands in California at the time[5][6][7] – Shyamasundar and Gurudas secured their consent to perform for charity at the concert, charging only the "musicians' union minimum" of $250.[9][23][24] Malati Dasi happened to hear Moby Grape, a relatively unknown group at the time, and she convinced the other team members to invite the band to play at the concert as well.[25][nb 3]

Another leading countercultural figure, the beatnik poet Allen Ginsberg, was a supporter of Prabhupada. He had met the swami earlier in New York[16] and assisted him in extending his United States visa.[26][nb 4] Despite disagreeing with many of Prabhupada's required prohibitions, especially the ones pertaining to drugs and promiscuity, Ginsberg often publicly sang the Hare Krishna mantra, which he had learned in India. He made the mantra part of his philosophy[27] and declared that it "brings a state of ecstasy."[28][nb 5] He was glad that Prabhupada, an authentic swami from India, was now trying to spread the chanting in America. Along with other countercultural ideologues like Timothy Leary, Gary Snyder, and Alan Watts, Ginsberg hoped to incorporate Prabhupada and the chanting of Hare Krishna into the hippie movement.[nb 6] Ginsberg agreed to take part in the Mantra-Rock Dance concert and to introduce the swami to the Haight-Ashbury hippie community.[27][29]

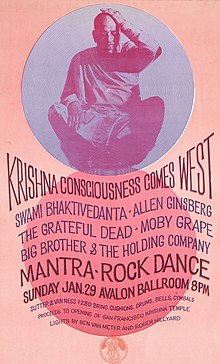

As for the choice of venue, the team considered both the Fillmore Auditorium and the Avalon Ballroom, finally settling on the latter as its impresario, Chet Helms, appeared to be "more sympathetic to the spirit of the concert"[30] and agreed to let it be used for a charity event. Artist Harvey Cohen, one of the first ISKCON followers, designed a Stanley Mouse-inspired promotional poster with a picture of Prabhupada, details of the event, and a request to "bring cushions, drums, bells, cymbals."[31] To generate interest among members of the countercultural community of Haight-Ashbury, Mukunda published an article entitled "The New Science" in the San Francisco Oracle, a local underground newspaper specializing in alternative spiritual and psychedelic topics.[32] He wrote:

The Haight-Ashbury district is soon to be honored by the presence of His Holiness, A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, who will conduct daily classes in the Bhagavad Gita, discussions, chanting, playing instruments, and devotional dancing in a small temple in the neighborhood. ... Swamiji's use of the Hare Krishna Mantra is already known throughout the United States. Swamiji's chanting and dancing is more effective than Hatha or Raja Yoga or listening to Ali Akbar Khan on acid or going to a mixed media rock dance.[33]

Ginsberg helped plan and organize a reception for Prabhupada, who was scheduled to arrive from New York on January 17, 1967. When the swami arrived at the San Francisco Airport, 50 to 100 hippies chanting "Hare Krishna" greeted him in the airport lounge with flowers.[16] A few days later the San Francisco Chronicle published an article entitled "Swami in the Hippie Land" in which Prabhupada answered the question, "Do you accept hippies in your temple?" by saying, "Hippies or anyone – I make no distinctions. Everyone is welcome."[34]

Event

editThe Mantra-Rock Dance was scheduled on Sunday evening, January 29, 1967 – a day of the week that Chet Helms deemed odd and unlikely to generate substantial attendance.[35] Admission was fixed at $2.50[3] and limited to door sales.[36] Despite the apprehensions of the organizers, by the beginning of the concert at 8 PM an audience of nearly 3,000 had gathered at the Avalon Ballroom,[37] filling the hall to its capacity.[38] Latecomers had to wait outside for vacancies in order to enter.[39] Participants were treated on prasad (sanctified food) consisting of orange slices[9] and, regardless of the prohibition on drugs, many in the crowd were smoking marijuana and taking other intoxicants.[37][40] However, the atmosphere in the hall was peaceful.[38] Strobe lights and a psychedelic liquid light show, along with pictures of Krishna and the words of the Hare Krishna mantra, were projected onto the walls.[41] A few Hells Angels were positioned in the back of the stage as the event's security guards.[9] Prabhupada's biographer Satsvarupa Dasa Goswami thus describes the Mantra-Rock Dance audience:

Almost everyone who came wore bright or unusual costumes: tribal robes, Mexican ponchos, Indian kurtas, "God's-eyes," feathers, and beads. Some hippies brought their own flutes, lutes, gourds, drums, rattles, horns, and guitars. The Hell's Angels, dirty-haired, wearing jeans, boots, and denim jackets and accompanied by their women, made their entrance, carrying chains, smoking cigarettes, and displaying their regalia of German helmets, emblazoned emblems, and so on – everything but their motorcycles, which they had parked outside.[38]

The evening opened with Prabhupada's followers – men in "Merlin gowns"[41] and women in saris – chanting Hare Krishna to an Indian tune, followed by Moby Grape.[41] When the swami himself arrived at 10 PM, the crowd of hippies rose to their feet to greet him respectfully with applause and cheers.[4] Gurudas, one of the event's organizers, describes the effect that Prabhupada's arrival had on the audience, "Then Swami Bhaktivedanta entered. He looked like a Vedic sage, exalted and otherworldly. As he advanced towards the stage, the crowd parted and made way for him, like the surfer riding a wave. He glided onto the stage, sat down and began playing the kartals."[9]

Ginsberg welcomed Prabhupada onto the stage and spoke of his own experiences chanting the Hare Krishna mantra. He translated the meaning of the Sanskrit term mantra as "mind deliverance" and recommended the early-morning kirtans at the local Radha-Krishna temple "for those coming down from LSD who want to stabilize their consciousness upon reentry," calling the temple's activity an "important community service." He introduced Prabhupada and thanked him for leaving his peaceful life in India to bring the mantra to New York's Lower East Side, "where it was probably most needed."[3][4][42]

After a short address by Prabhupada, Ginsberg sang "Hare Krishna" to the accompaniment of sitar, tambura, and drums, requesting the audience to "[j]ust sink into the sound vibration, and think of peace."[9] Then Prabhupada stood up and led the audience in dancing and singing, as the Grateful Dead, Big Brother and the Holding Company, and Moby Grape joined the chanting and accompanied the mantra with their musical instruments.[43][44][45] The audience eagerly responded, playing their own instruments and dancing in circles. The group chanting continued for almost two hours, and concluded with the swami's prayers in Sanskrit while the audience bowed down on the floor. After Prabhupada left, Janis Joplin took the stage, backed by Big Brother and the Holding Company, and continued the event with the songs "The House of the Rising Sun" and "Ball 'n' Chain" late into the night.[9][46]

Reaction and effect

editThe LSD pioneer Timothy Leary, who made an appearance at the Mantra-Rock Dance along with Augustus Owsley Stanley III and even paid the entrance fee,[3] pronounced the event a "beautiful night".[40] Later Ginsberg called the Mantra-Rock Dance "the height of Haight-Ashbury spiritual enthusiasm, the first time that there had been a music scene in San Francisco where everybody could be part of it and participate,"[4] while historians referred to it as "the ultimate high"[4][11] and "the major spiritual event of the San Francisco hippy era."[3]

Moby Grape's performance at the Mantra-Rock Dance catapulted the band onto the professional stage. They subsequently had gigs with The Doors at the Avalon Ballroom and at the "First Love Circus" at the Winterland Arena, and were soon signed to a contract with Columbia Records.[8]

The Mantra-Rock Dance helped raise around $2,000 for the temple and resulted in a massive influx of visitors at the temple's early morning services. Prabhupada's appearance at the Mantra-Rock Dance made such a deep impact on the Haight-Ashbury community that he became a cult hero to most of its groups and members, regardless of their attitudes towards his philosophy or the life restrictions that he taught.[47] The Hare Krishna mantra and dancing became adopted in some ways by all levels of the counterculture, including the Hells Angels,[48] and provided it with a "loose commonality" and reconciliation,[47] as well as with a viable alternative to drugs.[49] As the Hare Krishna movement's popularity with the Haight-Ashbury community continued to increase, Prabhupada and followers chanting and distributing prasad became a customary sight at important events in the locale.[10][37]

At the same time, as the core group of his followers continued to expand and become more serious about the spiritual discipline, Prabhupada conducted new Vaishnava initiations and named the San Francisco temple "New Jagannatha Puri" after introducing the worship of Jagannath deities of Krishna there.[19] Small replicas of these deities immediately became a "psychedelic hit" worn by many hippies on strings around their necks.[50]

Since the Mantra-Rock Dance brought the Hare Krishna movement to the wider attention of the American public,[10] Prabhupada's increased popularity attracted the interest of the mainstream media. Most notably, he was interviewed on ABC's The Les Crane Show and lectured on the philosophy of Krishna consciousness on a KPFK radio station program hosted by Peter Bergman.[51] Prabhupada's followers also spoke about their activities on the San Francisco radio station KFRC.[52]

On August 18, 2007, a free commemorative event dedicated to the 40th anniversary of the Mantra-Rock Dance was held at the People's Park in Berkeley, California.[13]

See also

editExplanatory notes

edit- ^ Joan Didion in her Slouching towards Bethlehem includes Mukunda's (referred to as Michael Grant) recollection of his initial involvement with Bhaktivedanta Swami's movement: "I've been associated with the Swami since about last July [of 1966]," Michael says. "See, the Swami came here from India and he was at this ashram in upstate New York and he just kept to himself and chanted a lot. For a couple of months. Pretty soon I helped him get his storefront in New York. Now it's an international movement, which we spread by teaching this chant." Michael is fingering his red wooden beads and I notice that I am the only person in the room with shoes on. "It's catching on like wildfire." (Didion 1990, p. 119)

- ^ After observing the event's sensual milieu, Prabhupada remarked, "This is no place for a brahmachari." (Brooks 1992, p. 79)

- ^ While sources concur on the appearance of the Grateful Dead, Janis Joplin with Big Brother and the Holding Company, and Moby Grape at the Mantra-Rock Dance, some of them also list Jefferson Airplane, Quicksilver Messenger Service, and Grace Slick among the event's performing musicians. (Brooks 1992, p. 79; Chryssides & Wilkins 2006, p. 213; Siegel 2004, pp. 8–10; and Dasa Goswami 1981, p. 10)

- ^ Addressing speculation that he was Ginsberg's guru, Prabhupada answered by saying, "I am nobody's guru. I am everybody's servant. Actually I am not even a servant; a servant of God is no ordinary thing." (Greene 2007, p. 85; Goswami & Dasi 2011, pp. 196–7)

- ^ The following quote from Mukunda in Joan Didion's Slouching towards Bethlehem hints at the difference between Ginsberg's and Bhaktivedanta Swami's perceptions of the Hare Krishna chanting: "Ginsberg calls the chant ecstasy, but the Swami says that's not exactly it."(Didion 1990, pp. 119–20)

- ^ (from the "Houseboat Summit" panel discussion, Sausalito, Calif., February 1967, Cohen 1991, p. 182):

Ginsberg: So what do you think of Swami Bhaktivedanta pleading for the acceptance of Krishna in every direction?

Snyder: Why, it's a lovely positive thing to say Krishna. It's a beautiful mythology and it's a beautiful practice.

Leary: Should be encouraged.

Ginsberg: He feels it's the one uniting thing. He feels a monopolistic unitary thing about it.

Watts: I'll tell you why I think he feels it. The mantras, the images of Krishna have in this culture no foul association. ... [W]hen somebody comes in from the Orient with a new religion which hasn't got any of these [horrible] associations in our minds, all the words are new, all the rites are new, and yet, somehow it has feeling in it, and we can get with that, you see, and we can dig that!

Citations

edit- ^ Cohen 1991, p. 106

- ^ Ellwood 1989, p. 106

- ^ a b c d e f g h Chryssides & Wilkins 2006, p. 213

- ^ a b c d e f g Greene 2007, p. 85

- ^ a b Schinder & Schwartz 2008, p. 335

- ^ a b Buckley 2003, p. 444

- ^ a b Buckley 2003, p. 91

- ^ a b Goswami & Dasi 2011, p. 160

- ^ a b c d e f g Siegel 2004, pp. 8–10

- ^ a b c d e Chryssides 2001, p. 173

- ^ a b Ellwood & Partin 1988, p. 68

- ^ Goswami & Dasi 2011, pp. 201, 262, 277

- ^ a b "Arts Calendar". Berkeley Daily Planet. August 17, 2007. Retrieved February 7, 2011.

- ^ Ellwood 1989, p. 102

- ^ Didion 1990, p. 119

- ^ a b c d Muster 1997, p. 25

- ^ Dasa Goswami 1981, p. 17

- ^ Goswami & Dasi 2011, pp. 100–1

- ^ a b Knott 1986, p. 33

- ^ Goswami & Dasi 2011, pp. 132–5

- ^ Goswami & Dasi 2011, p. 110

- ^ Dasa Goswami 1981, p. 9

- ^ Goswami & Dasi 2011, pp. 119, 127

- ^ Dasa Goswami 1981, p. 10

- ^ Goswami & Dasi 2011, p. 130

- ^ Goswami & Dasi 2011, pp. 76–7

- ^ a b Brooks 1992, pp. 78–9

- ^ Szatmary 1996, p. 149

- ^ Ginsberg & Morgan 1986, p. 36

- ^ Goswami & Dasi 2011, p. 126

- ^ Goswami & Dasi 2011, pp. 141–2

- ^ Goswami & Dasi 2011, p. 125

- ^ Cohen 1991, pp. 92, 96

- ^ Siegel 2004, p. 11

- ^ Goswami & Dasi 2011, p. 127

- ^ Goswami & Dasi 2011, p. 141

- ^ a b c Brooks 1992, p. 79

- ^ a b c Dasa Goswami 1981, p. 12

- ^ Goswami & Dasi 2011, p. 151

- ^ a b Muster 1997, p. 26

- ^ a b c Goswami & Dasi 2011, p. 152

- ^ Goswami & Dasi 2011, p. 154

- ^ Spörke 2003, p. 189

- ^ Tuedio & Spector 2010, p. 32

- ^ Joplin 1992, p. 182

- ^ Goswami & Dasi 2011, p. 159

- ^ a b Brooks 1992, pp. 79–80

- ^ Oakes 1969, p. 25

- ^ Ellwood 1989, pp. 106–7

- ^ Brooks 1992, p. 80

- ^ Goswami & Dasi 2011, pp. 262, 277

- ^ Goswami & Dasi 2011, p. 201

General and cited references

edit- Brooks, Charles R. (1992), The Hare Krishnas in India (reprint ed.), Delhi, India: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, ISBN 81-208-0939-4

- Buckley, Peter (2003), The rough guide to rock (3rd ed.), London, UK: Rough Guides, ISBN 1-84353-105-4

- Chryssides, George D. (2001), Exploring New Religions, New York, NY: Continuum International Publishing Group, ISBN 0-8264-5959-5

- Chryssides, George D.; Wilkins, Margaret Z. (2006), A Reader in New Religious Movements, London, UK: Continuum International Publishing Group, ISBN 0-8264-6168-9

- Cohen, Allen (1991), The San Francisco Oracle: The Psychedelic Newspaper of the Haight-Ashbury (1966–1968). Facsimile edition, Berkeley, CA: Regent Press, ISBN 0-916147-11-8

- Dasa Goswami, Satsvarupa (1981), Srila Prabhupada Lilamrta, Volume 3: Only he could lead them, San Francisco/India, vol. 3 (1st ed.), Los Angeles, CA: Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, ISBN 0-89213-110-1

- Didion, Joan (1990), Slouching towards Bethlehem, New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, ISBN 0374521727

- Ellwood, Robert S. (1989), "ISKCON and the Spirituality of the 60s", in Bromley, David G.; Shinn, Larry D. (eds.), Krishna Consciousness in the West, Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press, ISBN 0-8387-5144-X

- Ellwood, Robert S.; Partin, Harry Baxter (1988), Religious and Spiritual Groups in Modern America (2nd ed.), Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, ISBN 0-13-773045-4

- Ginsberg, Allen; Morgan, Bill (1986), Kanreki: A Tribute to Allen Ginsberg, Part 2, New York, NY: Lospecchio Press

- Goswami, Mukunda; Dasi, Mandira (2011), Miracle on Second Avenue, Badger, CA: Torchlight Publishing, ISBN 978-0-9817273-4-9

- Greene, Joshua M. (2007), Here Comes the Sun: The Spiritual and Musical Journey of George Harrison (reprint ed.), Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, ISBN 978-0-470-12780-3

- Joplin, Laura (1992), Love, Janis, New York, NY: Villard Books, ISBN 0-679-41605-6

- Knott, Kim (1986), My Sweet Lord: The Hare Krishna Movement, Wellingborough, UK: Aquarian Press, ISBN 0-85030-432-6

- Muster, Nori Jean (1997), Betrayal of the Spirit: My Life Behind the Headlines of the Hare Krishna Movement (reprint ed.), Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, ISBN 0-252-06566-2

- Oakes, Philip (February 1, 1969). "'Chanting Does Wonders' For New Missionary Group". The Calgary Herald. Calgary, Canada. p. 25. OCLC 70739047.

- Schinder, Scott; Schwartz, Andy (2008), Icons of Rock: Velvet Underground; The Grateful Dead; Frank Zappa; Led Zeppelin; Joni Mitchell; Pink Floyd; Neil Young; David Bowie; Bruce Springsteen; Ramones; U2; Nirvana, vol. 2, Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-313-33847-2

- Siegel, Roger (2004), By His Example : The Wit and Wisdom of A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, Badger, CA: Torchlight Publishing, ISBN 1-887089-36-5, OCLC 52970238

- Spörke, Michael (2003), Big Brother & the Holding Co. 1965–2003: Die Band, die Janis Joplin berühmt machte (in German), Kassel, Germany: BoD – Books on Demand, ISBN 3-8311-4823-6

- Szatmary, David P. (1996), Rockin' in Time: A Social History of Rock-and-Roll (3rd, illustrated ed.), Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, ISBN 0-13-440678-8

- Tuedio, James A.; Spector, Stan (2010), Grateful Dead in Concert: Essays on Live Improvisation, Jefferson, NC: McFarland, ISBN 978-0-7864-4357-4

External links

edit- YouTube video: Allen Ginsberg and a group of hippies receive Prabhupada at the San Francisco airport on January 17, 1967 (0:00–1:01).

- "Mantra-Rock Dance" revisited: commemoration of the 40th anniversary at the People's Park in Berkeley, California. August 18, 2007.