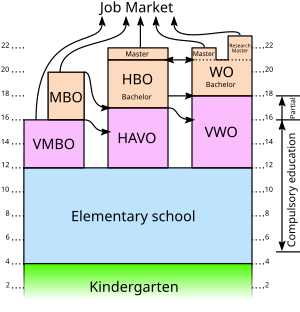

Education in the Netherlands is characterized by division: education is oriented toward the needs and background of the pupil. Education is divided over schools for different age groups, some of which are divided in streams for different educational levels. Schools are furthermore divided in public, special (religious), and general-special (neutral) schools,[1] although there are also a few private schools. The Dutch grading scale runs from 1 (very poor) to 10 (outstanding).

| |

| Ministry of Education, Culture and Science | |

|---|---|

| Minister of Education | Eppo Bruins and Mariëlle Paul |

| National education budget (2014) | |

| Budget | €32.1 billion ($42 billion) |

| General details | |

| Primary languages | Dutch Bilingual/Trilingual (with English, German, French or West Frisian (only in Friesland)) |

| Current system | 1968 (Mammoetwet). 1999 (latest revision). |

The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), coordinated by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), ranks the education in the Netherlands as the 16th best in the world as of 2018.[2] The Netherlands' educational standing compared to other nations has been declining since 2006, and is now only slightly above average.[3] School inspectors are warning that reading standards among primary school children are lower than 20 years ago, and the Netherlands has now dropped down the international rankings. A similar trend is seen in writing and reading, maths and science.[3] The country has an on-going teacher shortage and lack of new teachers.[3]

The average OECD performance of Dutch 15-year-olds in science and mathematics has declined, with the share of low performers in reading, mathematics and science developing a sharp upward trend.[4] The share of top performers in mathematics and science has also declined.[4][5]

General overview

editEducational policy is coordinated by the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science with municipal governments.

Compulsory education (leerplicht) in the Netherlands starts at the age of five, although in practice, most schools accept children from the age of four. From the age of sixteen there is a partial compulsory education (partiële leerplicht), meaning a pupil must attend some form of education for at least two days a week.[6] Compulsory education ends for pupils aged eighteen and up or when they get a diploma on the VWO, HAVO or MBO-2 level.

Public, special (religious), and general-special (neutral) schools[1] are government-financed, receiving equal financial support from the government if certain criteria are met. Although they are officially free of charge, these schools may ask for a parental contribution (ouderbijdrage). Private schools rely on their own funds, but they are highly uncommon in the Netherlands, to the extent that even the Dutch monarchs have traditionally attended special or public schools. Public schools are controlled by local governments. Special schools are controlled by a school board and are typically based on a particular religion; those that assume equality between religions are known as general-special schools. These differences are present in all levels of education.

As a result, there can be Catholic, Protestant, Jewish and Muslim elementary schools, high schools, and universities. A special school can reject applications of pupils whose parents or guardians disagree with the school's educational philosophy, but this is uncommon. In practice, there is little difference between special schools and public schools, except in traditionally religious areas of the Dutch Bible Belt. All school types (public, special and private) are under the jurisdiction of a government body called Inspectie van het Onderwijs (Inspection of Education, also known as Onderwijsinspectie) that can demand a school to change its educational policy and quality at the risk of closure.

In elementary and high schools, pupils are assessed annually by a team of teachers who determine whether they advanced enough to move on to the next grade. Forcing a pupil to retake the year (blijven zitten; literally, "remain seated") has a profound impact on the pupil's life in terms of social contacts and remaining in the educational system longer, but is very common, even in the most academic streams such as Gymnasium. Some schools are more likely to choose this option than others. In some schools mechanisms are in place to avert retaking years, such as remedial teaching and other forms of guidance or making them go to a different type of schooling, such as moving down from HAVO to VMBO. Retaking a year is also common in elementary schools. Gifted children are sometimes granted the opportunity to skip an entire year, yet this happens rarely and usually happens in elementary schools.

Elementary education

editBetween the ages of four and twelve, children attend elementary school (basisschool; literally, "foundation school"). This school has eight grades, called groep 1 (group 1) through groep 8 (group 8). School attendance is not necessary until group 2 (at age five), but almost all children commence school at age four (in group 1). Groups 1 and 2 used to be held in a separate institution akin to kindergarten (kleuterschool), until it was merged with elementary schools in 1985. Kindergartens continued to exist however, for children under the age of 5.

From group 3 on, children learn how to read, write and do arithmetic. Most schools teach English in groups 7 and 8, but some start as early as group 1. In group 8 the vast majority of schools administer an aptitude test called the Cito Eindtoets Basisonderwijs (literally, "Cito final test [of] primary education", often abbreviated to Citotoets (Cito test), developed by the Centraal instituut voor toetsontwikkeling[7] (Central Institute for Test Development)), which is designed to recommend the type of secondary education best suited for a pupil. In recent years, this test has gained authority, but the recommendation of the group 8 teacher along with the opinion of the pupil and his/her parents remains the crucial factor in choosing the right form of secondary education.

The Cito test is not mandatory; some schools instead administer the Nederlandse Intelligentietest voor Onderwijsniveau ("Dutch intelligence test for educational level", usually abbreviated to NIO-toets) or the Schooleindonderzoek ("School final test").

A considerable number of elementary schools are mostly based on a particular educational philosophy, for instance the Montessori Method, Pestalozzi Plan, Dalton Plan, Jena Plan, or Freinet.[1] Most of these are public schools, but some special schools also base themselves on one of these educational philosophies.

Secondary education

editAfter attending elementary education, children in the Netherlands (by that time usually 12 years old) go directly to high school (voortgezet onderwijs;[8] literally "continued education"). Informed by the advice of the elementary school and the results of the Cito test, a choice is made for either voorbereidend middelbaar beroepsonderwijs (VMBO), hoger algemeen voortgezet onderwijs (HAVO) or voorbereidend wetenschappelijk onderwijs (VWO) by the pupil and their parents. When it is not clear which type of secondary education best suits a pupil, or if the parents insist their child can handle a higher level of education than what was recommended to them, there is an orientation year for both VMBO/HAVO and HAVO/VWO to determine this. At some schools, it is not possible to do HAVO the 1st year, instead requiring students take the combination year. After one or two years, the pupil will continue in the normal curriculum of either level. A high school can offer one or more levels of education, at one or multiple locations. A focus on (financial) efficiency has led to more centralization, with large schools that offer education on all or most educational levels.

Because the Dutch educational system normally does not have middle schools or junior high schools, the first year of all levels in Dutch high schools is referred to as the brugklas (literally "bridge class"), as it connects the elementary school system to the secondary education system. During this year, pupils will gradually learn to cope with the differences between school systems, such as dealing with increased personal responsibility. Sometimes people also call the second year brugklas. Although the Dutch educational system in general does not have middle schools, there are around 10 official middle schools (called tussenschool) which replace 7th and 8th grade of middle school and 1st and 2nd year of high school.

It is possible for pupils who have attained the VMBO diploma to attend the final two years of HAVO level education and sit the HAVO exam, and for pupils with a HAVO diploma to attend the final two years of VWO level education and sit the VWO exam. The underlying rationale is that this grants pupils access to a more advanced level of higher education. This system acts as a safety net to diminish the negative effects of a child's immaturity or lack of self-knowledge. For example, when a bright pupil was sent to VMBO because they were unmotivated but later discovered their potential or has acquired the desire to achieve better, the pupil can still attain a higher level by moving on to HAVO, spending only one more year at school. Most schools do require a particular grade average to ensure the pupil is capable of handling the increased study load and higher difficulty level.

Aside from moving up, there is also a system in place where pupils can be demoted to a lower level of education. When for example a pupil has entered secondary education at a level they cannot cope with, or when they lack the interest to spend effort on their education resulting in poor grades, they can be sent from VWO to HAVO, from HAVO to VMBO, and from any level of VMBO to a lower level of VMBO.

VMBO

editThe VMBO (voorbereidend middelbaar beroepsonderwijs; literally "preparatory middle-level applied education", in international terms "pre-vocational education") education lasts four years, from the age of twelve to sixteen.[9] It combines vocational training with theoretical education in languages, mathematics, history, arts and sciences. Sixty percent of students nationally are enrolled in VMBO. Students cannot choose between the four different levels of VMBO that differ in the ratio of practical vocational training and theoretical education, but the level depends from the score.[9] Not all levels are necessarily taught in the same high school.

- Theoretische leerweg (VMBO-TL; literally "theoretical learning path") has the largest share of theoretical education. It prepares for middle management and the MBO level of tertiary education, and allows students to resume vocational training at HAVO level.[9] It was previously known as "MAVO".

- Gemengde leerweg (VMBO-GL; literally "mixed learning path") is in between VMBO-TL and VMBO-KBL. The progression route to graduation is similar to the VMBO-TL.[9]

- Kaderberoepsgerichte leerweg (VMBO-KBL; literally "middle management-oriented learning path") is composed of an equal amount of theoretical education and vocational training. It prepares for middle management and vocational training at the MBO level of tertiary education.

- Basisberoepsgerichte leerweg (VMBO-BBL; literally "basic profession-oriented learning path") emphasizes vocational training and prepares for vocational training at the MBO level of tertiary education.

- Praktijkonderwijs (literally "practical education") mainly consists of vocational training. It is tailored to pupils who would otherwise not be able to obtain a VMBO-diploma. This form of on-the-job training is aimed at allowing pupils to enter the job market directly.

At all of these levels, Leerwegondersteunend onderwijs (literally "learning path supporting education") is offered, which is intended for pupils with educational or behavioural problems. These pupils are taught in small classes by specialized teachers.

VMBO curriculum

editDuring the first two years, Dutch pupils are taught mathematics, Dutch, English, physical education, arts, and either history, geography, or a combined subject called mens en maatschappij or "M&M", meaning human and society in Dutch. They also get at least one year education in: biology, sex education (in public non-religious schools), arithmetics, economics (if not included in mens en maatschappij), a technical subject,[10] and a combination subject of physics and chemistry called NaSk.[11]

VMBO BB and KB

editFor their third and fourth year, VMBO BB and VMBO KB students have five core subjects in the curriculum: Dutch, English, CKV (standing for culturele en kunstzinnige vorming, "cultural and artistic education"), civics,[12] and physical education. They also get to choose two subjects via their chosen study program. There are ten official study programs.

| Study program | Contents |

|---|---|

| Economics & Business and Catering, Bakery & Recreation | Economics; choice between mathematics or a foreign language. |

| Care & Welfare | Biology; choice between mathematics, geography, and history. |

| Green ("Agriculture") | Mathematics; choice between NaSk1[a] and biology. |

| Services & Products ("Tech") | Choice of two between economics, mathematics, biology, and NaSk1. |

| 5 other technical programs | Mathematics and NaSk1 |

Students also choose two vocational subjects of their liking. Most schools offer only a limited selection of these programs, and some specialised schools only offer a single study program. At the end of the four years, the students take an exam in their two chosen subjects, as well as in Dutch and English.[13]

VMBO GL & TL

editVMBO GL or TL students need to follow a second foreign language in their first two years or the last two years of secondary school.[14] Four programs are offered in this curriculum: Care & Welfare, Economics, Tech, and Green ("Agriculture")[15] these are all equivalent to the programs of VMBO BB and KB. Besides this, students choose two subjects of their own liking. Because of this, more subjects are offered, such as NaSk2,[b] arts, music, and LO2, an advanced physical education course.

Selective secondary education

editSecondary education, which begins at the age of 12 and, as of 2008, is compulsory until the age of 18, is offered at several levels. The two programmes of general education that lead to higher education are HAVO (five years) and VWO (six years). Pupils are enrolled according to their ability, and although VWO is more rigorous, both HAVO and VWO can be characterised as selective types of secondary education. The HAVO diploma is the minimum requirement for admission to HBO (universities of applied sciences) but HBO admission is also possible upon achieving a diploma at MBO level. The VWO curriculum prepares pupils for university, and the VWO diploma grants access to WO (research universities), but it is also possible to enter WO universities after successfully completing the propaedeuse (first year) of HBO.

Curriculum

editThe first three years of both HAVO and VWO are called the basisvorming ("basic formation"). All pupils follow the same subjects: Dutch, mathematics, English, history, arts, at least two other foreign languages (mostly German and French), biology, physical education, geography, at least some form of arithmetic which since the school year of 2022/2023 can be given in combination with math and some form of physics and chemistry, usually combined into a single subject (natuur- en scheikunde or NaSk). During the third year students get a bit more controlled curriculum because they need to be at the level VMBO students must have reached for their exam. Because of this they get physics and chemistry taught as two different subjects, and they get economics as a subject. The last two years of HAVO and the last three years of VWO are referred to as the second phase (tweede fase), or upper secondary education. This part of the educational programme allows for differentiation by means of subject clusters that are called "profiles" (profielen). A profile is a set of different subjects that will make up for the largest part of the pupil's timetable. It emphasizes a specific area of study in which the pupil specializes. Compared to the HAVO route, the difficulty level of the profiles at the VWO is higher, lasts three years instead of two and requires a foreign language on atheneum and a classic language (Latin or Ancient Greek) on gymnasium level. Pupils pick one of four profiles towards the end of their third year:

- Cultuur en Maatschappij (C&M; literally "culture and society") emphasizes arts and foreign languages. A student needs to take a foreign language (French, German and occasionally Spanish, Russian, Arabic and Turkish). In the province of Friesland, West Frisian is also taught. An art class must be taken like drawing, visual arts or music. History is mandatory in this profile. On HAVO C&M is the only profile where mathematics is not required. On VWO the mathematics classes are math A or math C, both focusing on statistics and stochastics but whilst math A in the last year focuses on harder math like parts of calculus, math C is more repetition of previous math. This profile prepares for artistic and cultural training.

- Economie en Maatschappij (E&M; literally "economy and society") emphasizes social sciences and economics. In this profile history and economics (macro-economics) are mandatory. The mathematics class is math A which focuses on statistics and stochastics. Beside this a student on HAVO can choose geography, business economics (micro-economics) or a foreign language. VWO can only choose one of the first two. This profile prepares for management and business administration.

- Natuur en Gezondheid (N&G; literally "nature and health") emphasizes biology and natural sciences. A student must take chemistry and biology The mathematics classes are math A which focuses on statistics or stochastics and math B which focuses on algebra, geometry and calculus. A student must also choose either geography or physics. This profile is necessary to attend higher medical training.

- Natuur en Techniek (N&T; literally "nature and technology") emphasizes natural sciences. A student must take physics, chemistry and math B which focuses on algebra, geometry and calculus, and must choose biology or either "nature, life and technology" (NLT) or informatics (computer science); this depends on the school. This profile is necessary to attend technological and natural science training.

Because each profile is designed to prepare pupils for certain areas of study at the tertiary level, some HBO and WO studies require a specific profile because prerequisite knowledge is required. For example, one cannot study engineering without having attained a certificate in physics at the secondary educational level. Aside from the subjects in the profile, the curriculum is composed of a compulsory segment that includes Dutch, English, mathematics, civics and "cultural and artistic education" (CKV), and a free choice segment in which pupils can choose one subject of their liking. Picking particular subjects in the free curriculum space can result in multiple profiles, especially the profiles N&G and N&T that overlap to a large extent. Students then have a NG&NT profile. The requirement is to have a N&T profile with biology or a N&G with physics and math B. In the free choice section other subjects not offered in the profiles can also be offered like —BSM (advanced physical education) and maatschappijwetenschappen (social sciences).

HAVO

editThe HAVO (hoger algemeen voortgezet onderwijs; literally "higher general continued education") has five grades and is attended from age twelve to seventeen. A HAVO diploma provides access to the HBO level (polytechnic) of tertiary education.

VWO

editThe VWO (voorbereidend wetenschappelijk onderwijs; literally "preparatory scientific education") has six grades and is typically attended from age twelve to eighteen. A VWO diploma provides access to WO training, although universities may set their own admission criteria (e.g. based on profile or on certain subjects).

The VWO is divided into atheneum and gymnasium. A gymnasium programme is similar to the atheneum, except that Latin and Greek are compulsory courses. Not all schools teach the ancient languages throughout the first three years (the "basic training"), but if they do, Latin may start in either the first or the second year, while Greek may start in the second or third. At the end of the third and sometimes fourth year, a pupil may decide to take one or both languages in the second three years (the second phase), when the education in ancient languages is combined with education in ancient culture. The subject that they choose, although technically compulsory, is subtracted from their free space requirement.

VWO-plus, also known as atheneum-plus, VWO+, Masterclass or lyceum, offers extra subjects like philosophy, additional foreign languages and courses to introduce students to scholarly research. Schools offer this option rarely and sometimes only for the first three years, it is not an official school level.

Some schools offer bilingual VWO (Tweetalig VWO, or TVWO), where the majority of the lessons are taught in English. In some schools near the Dutch–German border, pupils may choose a form of TVWO that offers 50% of the lessons in German and 50% in Dutch.

VAVO

editVAVO (Voortgezet algemeen volwassenen onderwijs; literally "extended general adult education") is an adult school, which teaches VMBO/MAVO, HAVO or VWO, for students who in the past were unable to receive their diploma, who want to receive certificates for certain subjects only, or who for example received their diploma for HAVO but want to receive their VWO-diploma within one or two years.

International education

editAs of January 2015, the International Schools Consultancy (ISC) listed the Netherlands as having 152 international schools.[16] ISC defines an 'international school' in the following terms "ISC includes an international school if the school delivers a curriculum to any combination of pre-school, primary or secondary students, wholly or partly in English outside an English-speaking country, or if a school in a country where English is one of the official languages, offers an English-medium curriculum other than the country's national curriculum and is international in its orientation."[16] This definition is used by publications including The Economist.[17]

Vocational education and higher education

editIn the Netherlands there are 3 main educational routes after secondary education:

- MBO (middle-level applied education), which is the equivalent of junior college education. Designed to prepare students for either skilled trades and technical occupations and workers in support roles in professions such as engineering, accountancy, business administration, nursing, medicine, architecture, and criminology or for additional education at another college with more advanced academic material.[18]

- HBO (higher professional education), which is the equivalent of college education and has a professional orientation. The HBO is taught in vocational universities (hogescholen), of which there are over 40 in the Netherlands. Note that the hogescholen are not allowed to name themselves university in Dutch. This also stretches to English and therefore HBO institutions are known as universities of applied sciences.[19]

- WO (Scientific education), which is the equivalent of university level education and has an academic orientation.[19]

HBO graduates can be awarded with the Dutch title Baccalaureus (bc.) or Ingenieur (ing.). Usually their diploma states the English title Bachelor of Arts (BA), Bachelor of Laws (LLB) or Bachelor of Science (BSc). Instead of a BA, LLB or BSc, it's also possible that they receive a title which mentions the studied subject, for example Bachelor of Social Work or Bachelor of Nursing.

At a WO institution the following bachelor's and master's titles can be awarded. Bachelor's degrees: Bachelor of Arts (BA), Bachelor of Science (BSc) and Bachelor of Laws (LLB). Master's degrees: Master of Arts (MA), Master of Laws (LLM) and Master of Science (MSc). The PhD title is a research degree awarded upon completion and defense of a doctoral thesis.[20]

Vocational education

editMBO

editThe MBO (middelbaar beroepsonderwijs; literally "middle-level applied education") is oriented towards vocational training and is the equivalent of junior college education. Many pupils with a VMBO-diploma attend MBO. The MBO lasts one to four years, depending on the level. There are 4 levels offered to students:[9]

- MBO level 1: Assistant training. It lasts 1 year maximum. It is focused on simple executive tasks. If the student graduates, they can apply to MBO level 2.

- MBO level 2: Basic vocational education. The programme lasts 2 to 3 years and is focused on executive tasks.

- MBO level 3: The programme lasts 3 to 4 years. Students are taught to achieve their tasks independently.

- MBO level 4: Middle Management VET. It lasts 3 to 4 years and prepares for jobs with higher responsibility. It also opens the gates to Higher education.

At all levels, MBO offers 2 possible pathways: a school-based education, where Training within a company takes between 20 and 59% of the curriculum, or an apprenticeship education, where this training represents more than 60% of the study time. Both paths lead to the same certification.[9] Students in MBO are mostly between 16 and 35. Students of the "apprenticeship" path are overall older (25+).[9] After MBO (4 years), pupils can enroll in HBO or enter the job market. Many different MBO studies are typically offered at a regionaal opleidingen centrum (ROC; literally "regional education center"). Most ROCs are concentrated on one or several locations in larger cities. Exceptions include schools offering specialized MBO studies such as agriculture, and schools adapted to pupils with a learning disability that require training in small groups or at an individual level.

Higher education

editHigher education in the Netherlands is offered at two types of institutions: universities of applied sciences (hogescholen; HBO), open to graduates of HAVO, VWO, and MBO-4, and research universities (universiteiten; WO) open only to VWO-graduates and HBO graduates (including HBO propaedeuse-graduates). The former comprise general institutions and institutions specializing in a particular field, such as agriculture, fine and performing arts, or educational training, while the latter comprise twelve general universities as well as three technical universities.[21]

Since September 2002, the higher education system in the Netherlands has been organised around a three-cycle system consisting of bachelor's, master's and PhD degrees, to conform and standardize the teaching in both the HBO and the WO according to the Bologna process.[citation needed] At the same time, the ECTS credit system was adopted as a way of quantifying a student's workload (both contact hours, and hours spent studying and preparing assignments). Under Dutch law, one credit represents 28 hours of work and 60 credits represents one year of full-time study.[citation needed] Both systems have been adopted to improve international recognition and compliance.

Despite these changes, the binary system with a distinction between research-oriented education and professional higher education remains in use. These three types of degree programmes differ in terms of the number of credits required to complete the programme and the degree that is awarded. A WO bachelor's programme requires the completion of 180 credits (3 years) and graduates obtain the degree of Bachelor of Arts, Bachelor of Science or Bachelor of Laws degree (B.A./B.Sc./LL.B.), depending on the discipline.[citation needed] An HBO bachelor's programme requires the completion of 240 credits (4 years), and graduates obtain the title Bachelor of Arts (BA), Bachelor of Laws (LLB) or Bachelor of Science (BSc), or a degree indicating their field of study, for example Bachelor of Engineering (B. Eng.) or Bachelor of Nursing (B. Nursing).[citation needed] The old title appropriate to the discipline in question (bc., ing.) may still be used.

Master's programmes at the WO level mostly require the completion of 60 or 120 credits (1 or 2 years). Some programmes require 90 (1.5 years) or more than 120 credits. In engineering, agriculture, mathematics, and the natural sciences, 120 credits are always required, while in (veterinary) medicine or pharmacy the master's phase requires 180 credits (3 years). Other studies that usually have 60-credit "theoretical master's programmes" sometimes offer 120-credit technical or research masters. Graduates obtain the degree of Master of Arts, Master of Science, Master of Laws or the not legally recognized degree Master of Philosophy[22] (M.A./M.Sc./LL.M./M.Phil.), depending on the discipline. The old title appropriate to the discipline in question (drs., mr., ir.) may still be used. Master's programmes at the HBO level require the completion of 60 to 120 credits, and graduates obtain a degree indicating the field of study, for example Master of Social Work (MSW).

The third cycle of higher education is offered only by research universities, which are entitled to award the country's highest academic degree, the doctorate, which entitles a person to use the title Doctor (Dr.). The process by which a doctorate is obtained is referred to as "promotion" (promotie). The doctorate is primarily a research degree, for which a dissertation based on original research must be written and publicly defended. This research is typically conducted while working at a university as a promovendus (research assistant).

Requirements for admission

editTo enroll in a WO bachelor's programme, a student is required to hold a VWO diploma or to have completed the first year (60 credits) of an HBO programme resulting in a propaedeuse, often combined with additional (VWO) certificates. The minimum admission requirement for HBO is either a HAVO school diploma or a level-4 (highest) MBO diploma. In some cases, pupils are required to have completed a specific subject cluster. A quota (numerus fixus) applies to admission to certain programmes, primarily in the medical sciences, and places are allocated using a weighted lottery. Applicants older than 21 years who do not possess one of these qualifications can qualify for admission to higher education on the basis of an entrance examination and assessment.

For admission to all master's programmes, a bachelor's degree in one or more specified disciplines is required, in some cases in combination with other requirements. Graduates with an HBO bachelor's may have to complete additional requirements for admission to a WO master's programme. A pre-master programme may provide admission to a master's programme in a different discipline than that of the bachelor's degree.

Accreditation and quality assurance

editA guaranteed standard of higher education is maintained through a national system of legal regulation and quality assurance.

The Ministry of Education, Culture and Science is responsible for legislation pertaining to education. A system of accreditation was introduced in 2002. Since then, the new Accreditation Organization of the Netherlands and Flanders (NVAO) has been responsible for accreditation. According to the section of the Dutch Higher Education Act that deals with the accreditation of higher education (2002), degree programmes offered by research universities and universities of professional education will be evaluated according to established criteria, and programmes that meet those criteria will be accredited, that is, recognised for a period of six years. Only accredited programmes are eligible for government funding, and students receive financial aid only when enrolled in an accredited programme. Only accredited programmes issue legally recognised degrees. Accredited programmes are listed in the publicly accessible Central Register of Higher Education Study Programmes (CROHO).[23] Institutions are autonomous in their decision to offer non-accredited programmes, subject to internal quality assessment. These programmes do not receive government funding.

HBO

editThe HBO (Hoger beroepsonderwijs; literally "higher professional education") is oriented towards higher learning and professional training. After HBO (typically 4–6 years), pupils can enroll in a (professional) master's program (1–2 years) or enter the job market. In some situations, students with an MBO or a VWO diploma receive exemptions for certain courses, so the student can do HBO in three years. The HBO is taught in vocational universities (hogescholen), of which there are over 40 in the Netherlands, each of which offers a broad variety of programs, with the exception of some that specialize in arts or agriculture. Note that the hogescholen are not allowed to name themselves university in Dutch. This also stretches to English and therefore HBO institutions are known as universities of applied sciences.

WO

editThe WO (wetenschappelijk onderwijs; literally "scientific education") is only taught at research universities. It is oriented towards higher learning in the arts or sciences. After the bachelor's programme (typically 3 years), students can enroll in a master's programme (typically 1, 2 or 3 years) or enter the job market. After gaining a master, a student can apply for a 3 or 4 year PhD candidate position at a university (NB a master's degree is the mandatory entry level for the Dutch PhD program). There are four technical universities, an Open University, six general universities and four universities with unique specializations in the Netherlands,[24] although the specialized universities have increasingly added more general studies to their curriculum.

History of education

editA national system of education was introduced in the Netherlands around the year 1800. The Maatschappij tot Nut van 't Algemeen ("Society for the Common Good") took advantage of the revolutionary tide in the Batavian Republic to propose a number of educational reforms. The School Act of 1806 encouraged the establishment of primary schools in all municipalities and instated provincial supervision. It also introduced a mandatory curriculum comprising Dutch language, reading, writing, and arithmetics. History, geography, and modern languages such as French, German and English were optional subjects. All newly established schools needed consent from the authorities or would be disbanded as freedom of education was not proclaimed until the Constitutional Reform of 1848. In addition to primary education, gymnasia (or Latin schools) and universities constituted higher education. What could be considered secondary education or vocational training was unregulated.[25]

This situation changed in the second half of the nineteenth century in the wake of social and economic modernisation. In 1857, a Lower Education Act replaced the 1806 act, supplementing the mandatory curriculum with geometry, geography, history, natural sciences, and singing. Modern languages, mathematics, agronomy, gymnastics, drawing and needlework for girls were included as elective subjects. Schools offering one or more of these elective subjects were known as meer uitgebreid lager onderwijs ("more comprehensive lower education") or mulo, which became a new type of secondary education.[26] The Middle Education Act of 1863 introduced more types of secondary education at an intermediary level between mulo and gymnasium: the two-year burgerschool ("civic school"), the three or five-year hogere burgerschool ("higher civic school" or hbs) and the middelbare meisjesschool ("middle girls' school" or mms).[27]

The 1857 Lower Education Act retained the strictly secular nature of public education, but introduced the right of religious communities to establish private schools of an explicitly religious nature. However, these "special schools" received no funding from the government. In 1878, the liberal government introduced a bill that significantly increased the quality of education school were required to offer. While for public schools the accompanying costs were compensated by the government, special schools were still expected to bear the costs themselves, which threatened the continued existence of many special schools. This led the confessionals to start a campaign for the equal funding of special religious education that would become known as the school struggle. Equal funding was achieved in the Pacification of 1917.[28]

What resulted from the 1857 and 1863 acts was a stratified system where school types were grouped into three "layers" intended for different socioeconomic classes and designed around different educational philosophies. Lower education (primary schools, mulo and vocational schools) was designed to prepare children from working class or lower-middle-class backgrounds for a specific vocation. "Middle" education (mms, hbs and polytechnics) was intended to equip children from middle-class backgrounds with general knowledge about modern society with which they could occupy leading positions in areas such as commerce and technology. Finally, higher education (gymnasium and university) was intended for the classical and intellectual education of children from upper middle and upper-class backgrounds. This distinction between middle and higher education based on the type of education rather than the students' age would gradually alter in the twentieth century. From 1917 onward, an hbs diploma would grant access to a number of courses at universities, while the lyceum, combining hbs and gymnasium, became an increasingly common type of school.[29]

The introduction of the so-called Kinderwetje (literally "little children's act") by legislator Samuel van Houten in 1874 forbade child labour under the age of 12. An amendment in 1900 led to compulsory education for children aged 6 to 12 in 1901.[30] The introduction of compulsory education, in combination with the increasing complexity of the economy, led to a significant increase in children attending secondary education, especially from the 1920s onward.[29]

Thus, by the 1960s, a range of school types existed:

- Kleuterschool - kindergarten (ages 4–6).

- Lagere school - primary education, (ages 6–12), followed by either;

- Individueel technisch onderwijs (ito; literally "individual technical education") - now vmbo - praktijkonderwijs (ages 12–16).

- Ambachtsschool (vocational school) - comparable with vmbo - gemengde leerweg, but there was more emphasis on thorough technical knowledge (ages 12–16).

- (Meer) Uitgebreid lager onderwijs (mulo, later ulo; literally "(more) comprehensive lower education") - comparable with vmbo - theoretical learning path (ages 12–16).

- Hogere burgerschool (hbs; literally "higher civic school") - comparable with atheneum (ages 12–17).

- Middelbare meisjesschool (mms; literally "middle girls' school") - comparable with havo (ages 12–17).

- Gymnasium - secondary education, comparable with atheneum with compulsory Greek and Latin added (ages 12 to 18). At the age of 15 one could choose between the alpha profile (gymnasium-α; mostly languages, including compulsory Greek and Latin) or the beta profile (gymnasium-β; mostly natural sciences and mathematics). A student wanting to complete gymnasium-β would have to pass exams in the languages Ancient Greek, Latin, French, German, English, Dutch (all consisting of three separate parts: an oral book report, a written essay, and a written summary), pass the sciences physics, chemistry, biology, and mathematics (in mathematics, students were assigned to two of the three sub-fields analytic geometry/algebra, trigonometry, and solid geometry based on a draw), and attend history and geography, which were taught until the final year without examinations.

- Lyceum - a combination of gymnasium and hbs, with alpha and beta streams which pupils elected after a two-year (sometimes one-year) bridging period (ages 12–18).

- Middelbare and hogere technische school (mts/hts; literally middle and higher applied/technical training), similar to polytechnic education.

- University - only after completing hbs, mms, gymnasium or hts.

The different forms of secondary education were streamlined in the Wet op het voortgezet onderwijs (literally "law on secondary education") in 1963 at the initiative of legislator Jo Cals. The law is more widely known as the Mammoetwet (literally, "mammoth act"), a name it got when ARP member of parliament Anton Bernard Roosjen was reported to have said "Let that mammoth remain in fairyland" because he considered the reforms too extensive.[31] The law was enforced in 1968. It introduced four streams of secondary education, depending on the capabilities of the students (lts/vbo, mavo, havo and vwo) and expanded compulsory education to 9 years. In 1975 this was changed to 10 years.

The law created a system of secondary education on which the current secondary school is based albeit with significant adaptations. Reforms in the late 1990s aimed at introducing information management skills, increasing the pupils' autonomy and personal responsibility, and promoting integration between different subjects. Lts/vbo and mavo were fused into vmbo, while the structure of havo and vwo were changed by the introduction of a three-year basisvorming (primary secondary education; literally, "basic forming"), followed by the tweede fase (upper secondary education; literally, second phase"). The basisvorming standardized subjects for the first three years of secondary education and introduced two new compulsory subjects (technical skills and care skills), while the tweede fase allowed for differentiation through profiles.

The influx and emancipation of workers from Islamic countries led to the introduction of Islamic schools. In 2003, in total 35 Islamic schools were in operation.[32]

By 2004, the municipalities of the Netherlands were obliged to activate a regional care structure for individual students dealing with health and social problems. Each school was obliged to activate a care team at least composed by a physician/nurse, a school social worker and the school care coordinator. In the context of the schoolBeat project, each primary and secondary school of the Maastricht region designated a professional advisor who was employed by a drug prevention, welfare or mental health organization closely linked to the regional public health institute.[33]

Terms and school holidays

editIn general, all schools in the Netherlands observe a summer holiday, and several weeks of one or two-week holidays during the year. Also schools are closed during public holidays. Academic terms only exist at the tertiary education level. Institutions are free to divide their year, but it is most commonly organized into four quadmesters.

The summer holiday lasts six weeks in elementary school, and starts and ends in different weeks for the northern, middle and southern regions of the country to prevent the national population from all going on vacation simultaneously. For the six-week summer holidays of all high schools, the same system applies. Universities have longer holidays (about two months, but this may include re-examinations) and usually start the year in late August or early September. The summer holiday is followed by a one-week autumn holiday in the second half of October at all levels except for most research universities. At elementary and high school levels, the week depends on the north/middle/south division also used around the summer holidays. There is a two-week Christmas holiday that includes New Year's in the second half of December, and a one-week spring holiday in the second half of February (around Carnival). The last school holiday of the year is a one- or two-week May holiday around 27 April (Kings Day); sometimes including Ascension Day. Easter does not have a week of holiday, schools are only closed on Good Friday and Easter Monday. The summer holiday dates are compulsory, the other dates are government recommendations and can be changed by each school, as long as the right number of weeks is observed.

Criticism

editThe Dutch educational system divides children in educational levels around the age of 12.[34] In the last year of primary school, a test, most commonly the "Cito Eindtoets Basisonderwijs", is taken to help choose the appropriate level of secondary education/school type. Although the ensuing recommendation is not binding, it does have great influence on the decision-making process. Unless caretakers identify the need,[35] in most cases an IQ test is not given to a child, which may result in some children who for various secondary reasons do not function well at school, but who do have the academic ability to learn at the higher levels, mistakenly being sent to the lower levels of education.[36] Within a few years these children can fall far behind in development compared to their peers who were sent to the higher levels.[citation needed]

It is possible for students to move up (or down) from one level to another level. If there is doubt early on about the level chosen, an orientation year may be offered. However, moving up a level later on may require a lot of extra effort, motivation and time resulting in some students not reaching their full potential.[citation needed]

Research has shown that 30% of gifted children[37] are (mistakenly) advised to attend the VMBO, the lower level to which 60% of twelve-year-olds are initially sent. In this particular group of children there is a higher than normal percentage of drop-outs (leaving school without any diploma) or resorting to buying a degree online.[38]

Although IQ testing may aid to reduce mistakes in choosing levels, research has also shown that IQ is not fixed at the age of 12[39] and may still improve with exposure to the proper educational stimuli, which the current Dutch system by design (early separation into levels) may fail to provide.

Another area of concern is that although parents have the right to have their voice heard in the school's decision-making process, not all parents make use of this right equally, resulting in unequal opportunities for children.[40]

A recent study by the University of Groningen has also shown strong correlation between lower parental income and advice given to students to follow lower education https://kansenkaart.nl/maps/schooladvieslager

The Programme for International Student Assessment has found that the Netherlands' educational standing compared to other nations has been declining since 2006, and is now only slightly above average.[41] School inspectors are warning that reading standards among primary school children are lower than 20 years ago, and the Netherlands has now dropped down the international rankings. A similar trend is seen in arithmetic, maths and science.[42]

See also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c "Pagina niet gevonden – LOBO". Archived from the original on 2015-06-21. Retrieved 2011-04-18.

- ^ "OECD.org" (PDF).

- ^ a b c "Compare your country to the OECD average". PISA. OECD. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- ^ a b "Compare your country - PISA 2018".

- ^ "OECD.org" (PDF).

- ^ "Leerplicht". www.rijksoverheid.nl (in Dutch). Ministerie van Onderwijs Cultuur en Wetenschap. 11 December 2009. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- ^ "Cito - toetsen, examens, volgsystemen, certificering & onderzoek".

- ^ "Voortgezet onderwijs - Rijksoverheid.nl". 25 January 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Vocational Education in the Netherlands". UNESCO-UNEVOC. August 2012. Retrieved 10 July 2014.

- ^ "Welke vakken krijg je op het vmbo en de mavo?". 24 October 2022.

- ^ a b Stoop, Door NU nl/Scholieren com/Ivana (2016-05-26). "NaSk 2-examen op vmbo makkelijker dan NaSk 1". NU (in Dutch). Retrieved 2023-06-03.

- ^ Ministerie van Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschap (2016-03-22). "Hoe zit het vmbo in elkaar? - Rijksoverheid.nl". www.rijksoverheid.nl (in Dutch). Retrieved 2023-06-03.

- ^ "Alles over profielkeuze!".

- ^ "Kerndoelen". SLO (in Dutch). Retrieved 2023-06-03.

- ^ www.weareyou.com, We are you. "Home". KiesMBO (in Dutch). Retrieved 2023-06-03.

- ^ a b "International School Consultancy Group > Information > ISC News". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04.

- ^ "The new local". The Economist. 17 December 2014.

- ^ "Secondary vocational education (MBO) - Secondary vocational education (MBO) and higher education - Government.nl". 16 December 2011.

- ^ a b "Higher education - Secondary vocational education (MBO) and higher education - Government.nl". 16 December 2011.

- ^ "What's the difference between HBO and WO?". www.tudelft.nl. Archived from the original on 2019-05-06.

- ^ "Alle universiteiten in Nederland". MijnStudentenleven. 15 January 2014.

- ^ The Dutch Department of Education, Culture and Science has decided not to recognize the MPhil degree. Accordingly, some Dutch universities have decided to continue to grant the MPhil degree but also offer a legally recognized degree such as M.A. or M.Sc. to those who receive the M.Phil. degree, see e.g. De MPhil graad wordt niet meer verleend Archived July 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ The CROHO register is the list of all recognized Dutch studies offered at faculties, past or present, since the recognition system was introduced in the Netherlands. It is available at IB-groep.nl Archived 2009-06-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ VSNU (2011). Is er geen efficiencywinst te halen wanneer Nederlandse universiteiten meer gaan samenwerken en zich verder specialiseren? Archived 2012-03-20 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- ^ Boekholt & De Booy 1987, p. 99.

- ^ Boekholt & De Booy 1987, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Boekholt & De Booy 1987, pp. 183–184.

- ^ Boekholt & De Booy 1987, pp. 212–214.

- ^ a b Boekholt & De Booy 1987, pp. 257–259.

- ^ Boekholt & De Booy 1987, p. 153.

- ^ Trouw (in Dutch)

- ^ W.A. Shadid (2003). "Controlling lessons on religion on Islamic schools, based on an article in Vernieuwing. Tijdschrift voor Onderwijs en Opvoeding". Interculturele communicatie (in Dutch). Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- ^ Leurs, Mariken; Schaalma, Herman; Jansen, Maria; Mur-Veeman, Ingrid; St Leger, Lawrence; De Vries, Nanne (September 1, 2005). Development of a collaborative model to improve school health promotion in the Netherlands. Vol. 20. Oxford University Press. pp. 296–305. doi:10.1093/heapro/dai004. ISSN 0957-4824. OCLC 1133727050. PMID 15797902. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ "Map of Dutch education system" (PDF).

- ^ "Slachtoffer van de Cito-toets - Sargasso". 6 March 2011.

- ^ "De Citotoets geeft nog vaak een verkeerd advies - Binnenland - Voor nieuws, achtergronden en columns". De Volkskrant.

- ^ "Hoogbegaafdheid". Centrum Regenboogkind.

- ^ "Diploma kopen met DUO registratie in Nederland of België⭐" (in Dutch). Retrieved 2023-05-29.

- ^ Bouchard, Thomas J. (2013). "The Wilson Effect: The Increase in Heritability of IQ With Age". Twin Research and Human Genetics. 16 (5): 923–930. doi:10.1017/thg.2013.54. ISSN 1832-4274. PMID 23919982. S2CID 13747480.

- ^ Aroon, Shiam (1 June 2014). "WFT basis". Beroepen.nl (in Dutch). Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- ^ "Compare your country to the OECD average". PISA. OECD. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- ^ "Education standards at Dutch schools have been slipping for 20 years: inspectors". DutchNews.nl. DutchNews. 11 April 2018. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

Sources

edit- Boekholt, P.Th.F.M.; De Booy, E.P. (1987). Geschiedenis van de school in Nederland. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

Further reading

edit- Passow, A. Harry et al. The National Case Study: An Empirical Comparative Study of Twenty-One Educational Systems. (1976) online

- Ministerie van Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschap. Algemene informatie over de leerplicht, retrieved June 23, 2006.

External links

edit- Netherlands Organisation for Internationalisation of Higher Education

- Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science

- Information on education in Netherlands, OECD - Contains indicators and information about Netherlands and how it compares to other OECD and non-OECD countries

- Vocational education in the Netherlands, UNESCO-UNEVOC(2012) - Overview of the vocational system

- Diagram of Dutch education system, OECD - Using 1997 ISCED classification of programmes and typical ages. Also in Dutch

- Education in the Netherlands, a webdossier of Education Worldwide, a portal of the German Education Server