This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (February 2019) |

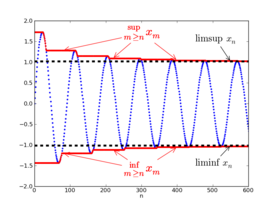

In mathematics, the limit inferior and limit superior of a sequence can be thought of as limiting (that is, eventual and extreme) bounds on the sequence. They can be thought of in a similar fashion for a function (see limit of a function). For a set, they are the infimum and supremum of the set's limit points, respectively. In general, when there are multiple objects around which a sequence, function, or set accumulates, the inferior and superior limits extract the smallest and largest of them; the type of object and the measure of size is context-dependent, but the notion of extreme limits is invariant. Limit inferior is also called infimum limit, limit infimum, liminf, inferior limit, lower limit, or inner limit; limit superior is also known as supremum limit, limit supremum, limsup, superior limit, upper limit, or outer limit.

The limit inferior of a sequence is denoted by and the limit superior of a sequence is denoted by

Definition for sequences

editThe limit inferior of a sequence (xn) is defined by or

Similarly, the limit superior of (xn) is defined by or

Alternatively, the notations and are sometimes used.

The limits superior and inferior can equivalently be defined using the concept of subsequential limits of the sequence .[1] An element of the extended real numbers is a subsequential limit of if there exists a strictly increasing sequence of natural numbers such that . If is the set of all subsequential limits of , then

and

If the terms in the sequence are real numbers, the limit superior and limit inferior always exist, as the real numbers together with ±∞ (i.e. the extended real number line) are complete. More generally, these definitions make sense in any partially ordered set, provided the suprema and infima exist, such as in a complete lattice.

Whenever the ordinary limit exists, the limit inferior and limit superior are both equal to it; therefore, each can be considered a generalization of the ordinary limit which is primarily interesting in cases where the limit does not exist. Whenever lim inf xn and lim sup xn both exist, we have

The limits inferior and superior are related to big-O notation in that they bound a sequence only "in the limit"; the sequence may exceed the bound. However, with big-O notation the sequence can only exceed the bound in a finite prefix of the sequence, whereas the limit superior of a sequence like e−n may actually be less than all elements of the sequence. The only promise made is that some tail of the sequence can be bounded above by the limit superior plus an arbitrarily small positive constant, and bounded below by the limit inferior minus an arbitrarily small positive constant.

The limit superior and limit inferior of a sequence are a special case of those of a function (see below).

The case of sequences of real numbers

editIn mathematical analysis, limit superior and limit inferior are important tools for studying sequences of real numbers. Since the supremum and infimum of an unbounded set of real numbers may not exist (the reals are not a complete lattice), it is convenient to consider sequences in the affinely extended real number system: we add the positive and negative infinities to the real line to give the complete totally ordered set [−∞,∞], which is a complete lattice.

Interpretation

editConsider a sequence consisting of real numbers. Assume that the limit superior and limit inferior are real numbers (so, not infinite).

- The limit superior of is the smallest real number such that, for any positive real number , there exists a natural number such that for all . In other words, any number larger than the limit superior is an eventual upper bound for the sequence. Only a finite number of elements of the sequence are greater than .

- The limit inferior of is the largest real number such that, for any positive real number , there exists a natural number such that for all . In other words, any number below the limit inferior is an eventual lower bound for the sequence. Only a finite number of elements of the sequence are less than .

Properties

editThe relationship of limit inferior and limit superior for sequences of real numbers is as follows:

As mentioned earlier, it is convenient to extend to Then, in converges if and only if in which case is equal to their common value. (Note that when working just in convergence to or would not be considered as convergence.) Since the limit inferior is at most the limit superior, the following conditions hold

If and , then the interval need not contain any of the numbers but every slight enlargement for arbitrarily small will contain for all but finitely many indices In fact, the interval is the smallest closed interval with this property. We can formalize this property like this: there exist subsequences and of (where and are increasing) for which we have

On the other hand, there exists a so that for all

To recapitulate:

- If is greater than the limit superior, there are at most finitely many greater than if it is less, there are infinitely many.

- If is less than the limit inferior, there are at most finitely many less than if it is greater, there are infinitely many.

Conversely, it can also be shown that:

- If there are infinitely many greater than or equal to , then is lesser than or equal to the limit supremum; if there are only finitely many greater than , then is greater than or equal to the limit supremum.

- If there are infinitely many lesser than or equal to , then is greater than or equal to the limit inferior; if there are only finitely many lesser than , then is lesser than or equal to the limit inferior.[2]

In general, The liminf and limsup of a sequence are respectively the smallest and greatest cluster points.[3]

- For any two sequences of real numbers the limit superior satisfies subadditivity whenever the right side of the inequality is defined (that is, not or ):

Analogously, the limit inferior satisfies superadditivity: In the particular case that one of the sequences actually converges, say then the inequalities above become equalities (with or being replaced by ).

- For any two sequences of non-negative real numbers the inequalities and

hold whenever the right-hand side is not of the form

If exists (including the case ) and then provided that is not of the form

Examples

edit- As an example, consider the sequence given by the sine function: Using the fact that π is irrational, it follows that and (This is because the sequence is equidistributed mod 2π, a consequence of the equidistribution theorem.)

- An example from number theory is where is the -th prime number.

- The value of this limit inferior is conjectured to be 2 – this is the twin prime conjecture – but as of April 2014[update] has only been proven to be less than or equal to 246.[4] The corresponding limit superior is , because there are arbitrarily large gaps between consecutive primes.

Real-valued functions

editAssume that a function is defined from a subset of the real numbers to the real numbers. As in the case for sequences, the limit inferior and limit superior are always well-defined if we allow the values +∞ and −∞; in fact, if both agree then the limit exists and is equal to their common value (again possibly including the infinities). For example, given , we have and . The difference between the two is a rough measure of how "wildly" the function oscillates, and in observation of this fact, it is called the oscillation of f at 0. This idea of oscillation is sufficient to, for example, characterize Riemann-integrable functions as continuous except on a set of measure zero.[5] Note that points of nonzero oscillation (i.e., points at which f is "badly behaved") are discontinuities which, unless they make up a set of zero, are confined to a negligible set.

Functions from topological spaces to complete lattices

editFunctions from metric spaces

editThere is a notion of limsup and liminf for functions defined on a metric space whose relationship to limits of real-valued functions mirrors that of the relation between the limsup, liminf, and the limit of a real sequence. Take a metric space , a subspace contained in , and a function . Define, for any limit point of ,

and

where denotes the metric ball of radius about .

Note that as ε shrinks, the supremum of the function over the ball is non-increasing (strictly decreasing or remaining the same), so we have

and similarly

Functions from topological spaces

editThis finally motivates the definitions for general topological spaces. Take X, E and a as before, but now let X be a topological space. In this case, we replace metric balls with neighborhoods:

(there is a way to write the formula using "lim" using nets and the neighborhood filter). This version is often useful in discussions of semi-continuity which crop up in analysis quite often. An interesting note is that this version subsumes the sequential version by considering sequences as functions from the natural numbers as a topological subspace of the extended real line, into the space (the closure of N in [−∞,∞], the extended real number line, is N ∪ {∞}.)

Sequences of sets

editThe power set ℘(X) of a set X is a complete lattice that is ordered by set inclusion, and so the supremum and infimum of any set of subsets (in terms of set inclusion) always exist. In particular, every subset Y of X is bounded above by X and below by the empty set ∅ because ∅ ⊆ Y ⊆ X. Hence, it is possible (and sometimes useful) to consider superior and inferior limits of sequences in ℘(X) (i.e., sequences of subsets of X).

There are two common ways to define the limit of sequences of sets. In both cases:

- The sequence accumulates around sets of points rather than single points themselves. That is, because each element of the sequence is itself a set, there exist accumulation sets that are somehow nearby to infinitely many elements of the sequence.

- The supremum/superior/outer limit is a set that joins these accumulation sets together. That is, it is the union of all of the accumulation sets. When ordering by set inclusion, the supremum limit is the least upper bound on the set of accumulation points because it contains each of them. Hence, it is the supremum of the limit points.

- The infimum/inferior/inner limit is a set where all of these accumulation sets meet. That is, it is the intersection of all of the accumulation sets. When ordering by set inclusion, the infimum limit is the greatest lower bound on the set of accumulation points because it is contained in each of them. Hence, it is the infimum of the limit points.

- Because ordering is by set inclusion, then the outer limit will always contain the inner limit (i.e., lim inf Xn ⊆ lim sup Xn). Hence, when considering the convergence of a sequence of sets, it generally suffices to consider the convergence of the outer limit of that sequence.

The difference between the two definitions involves how the topology (i.e., how to quantify separation) is defined. In fact, the second definition is identical to the first when the discrete metric is used to induce the topology on X.

General set convergence

editA sequence of sets in a metrizable space approaches a limiting set when the elements of each member of the sequence approach the elements of the limiting set. In particular, if is a sequence of subsets of then:

- which is also called the outer limit, consists of those elements which are limits of points in taken from (countably) infinitely many That is, if and only if there exists a sequence of points and a subsequence of such that and

- which is also called the inner limit, consists of those elements which are limits of points in for all but finitely many (that is, cofinitely many ). That is, if and only if there exists a sequence of points such that and

The limit exists if and only if and agree, in which case [6] The outer and inner limits should not be confused with the set-theoretic limits superior and inferior, as the latter sets are not sensitive to the topological structure of the space.

Special case: discrete metric

editThis is the definition used in measure theory and probability. Further discussion and examples from the set-theoretic point of view, as opposed to the topological point of view discussed below, are at set-theoretic limit.

By this definition, a sequence of sets approaches a limiting set when the limiting set includes elements which are in all except finitely many sets of the sequence and does not include elements which are in all except finitely many complements of sets of the sequence. That is, this case specializes the general definition when the topology on set X is induced from the discrete metric.

Specifically, for points x, y ∈ X, the discrete metric is defined by

under which a sequence of points (xk) converges to point x ∈ X if and only if xk = x for all but finitely many k. Therefore, if the limit set exists it contains the points and only the points which are in all except finitely many of the sets of the sequence. Since convergence in the discrete metric is the strictest form of convergence (i.e., requires the most), this definition of a limit set is the strictest possible.

If (Xn) is a sequence of subsets of X, then the following always exist:

- lim sup Xn consists of elements of X which belong to Xn for infinitely many n (see countably infinite). That is, x ∈ lim sup Xn if and only if there exists a subsequence (Xnk) of (Xn) such that x ∈ Xnk for all k.

- lim inf Xn consists of elements of X which belong to Xn for all except finitely many n (i.e., for cofinitely many n). That is, x ∈ lim inf Xn if and only if there exists some m > 0 such that x ∈ Xn for all n > m.

Observe that x ∈ lim sup Xn if and only if x ∉ lim inf Xnc.

- lim Xn exists if and only if lim inf Xn and lim sup Xn agree, in which case lim Xn = lim sup Xn = lim inf Xn.

In this sense, the sequence has a limit so long as every point in X either appears in all except finitely many Xn or appears in all except finitely many Xnc. [7]

Using the standard parlance of set theory, set inclusion provides a partial ordering on the collection of all subsets of X that allows set intersection to generate a greatest lower bound and set union to generate a least upper bound. Thus, the infimum or meet of a collection of subsets is the greatest lower bound while the supremum or join is the least upper bound. In this context, the inner limit, lim inf Xn, is the largest meeting of tails of the sequence, and the outer limit, lim sup Xn, is the smallest joining of tails of the sequence. The following makes this precise.

- Let In be the meet of the nth tail of the sequence. That is,

- The sequence (In) is non-decreasing (i.e. In ⊆ In+1) because each In+1 is the intersection of fewer sets than In. The least upper bound on this sequence of meets of tails is

- So the limit infimum contains all subsets which are lower bounds for all but finitely many sets of the sequence.

- Similarly, let Jn be the join of the nth tail of the sequence. That is,

- The sequence (Jn) is non-increasing (i.e. Jn ⊇ Jn+1) because each Jn+1 is the union of fewer sets than Jn. The greatest lower bound on this sequence of joins of tails is

- So the limit supremum is contained in all subsets which are upper bounds for all but finitely many sets of the sequence.

Examples

editThe following are several set convergence examples. They have been broken into sections with respect to the metric used to induce the topology on set X.

- Using the discrete metric

- The Borel–Cantelli lemma is an example application of these constructs.

- Using either the discrete metric or the Euclidean metric

- Consider the set X = {0,1} and the sequence of subsets:

- The "odd" and "even" elements of this sequence form two subsequences, ({0}, {0}, {0}, ...) and ({1}, {1}, {1}, ...), which have limit points 0 and 1, respectively, and so the outer or superior limit is the set {0,1} of these two points. However, there are no limit points that can be taken from the (Xn) sequence as a whole, and so the interior or inferior limit is the empty set { }. That is,

- lim sup Xn = {0,1}

- lim inf Xn = { }

- However, for (Yn) = ({0}, {0}, {0}, ...) and (Zn) = ({1}, {1}, {1}, ...):

- lim sup Yn = lim inf Yn = lim Yn = {0}

- lim sup Zn = lim inf Zn = lim Zn = {1}

- Consider the set X = {50, 20, −100, −25, 0, 1} and the sequence of subsets:

- As in the previous two examples,

- lim sup Xn = {0,1}

- lim inf Xn = { }

- That is, the four elements that do not match the pattern do not affect the lim inf and lim sup because there are only finitely many of them. In fact, these elements could be placed anywhere in the sequence. So long as the tails of the sequence are maintained, the outer and inner limits will be unchanged. The related concepts of essential inner and outer limits, which use the essential supremum and essential infimum, provide an important modification that "squashes" countably many (rather than just finitely many) interstitial additions.

- Using the Euclidean metric

- Consider the sequence of subsets of rational numbers:

- The "odd" and "even" elements of this sequence form two subsequences, ({0}, {1/2}, {2/3}, {3/4}, ...) and ({1}, {1/2}, {1/3}, {1/4}, ...), which have limit points 1 and 0, respectively, and so the outer or superior limit is the set {0,1} of these two points. However, there are no limit points that can be taken from the (Xn) sequence as a whole, and so the interior or inferior limit is the empty set { }. So, as in the previous example,

- lim sup Xn = {0,1}

- lim inf Xn = { }

- However, for (Yn) = ({0}, {1/2}, {2/3}, {3/4}, ...) and (Zn) = ({1}, {1/2}, {1/3}, {1/4}, ...):

- lim sup Yn = lim inf Yn = lim Yn = {1}

- lim sup Zn = lim inf Zn = lim Zn = {0}

- In each of these four cases, the elements of the limiting sets are not elements of any of the sets from the original sequence.

- The Ω limit (i.e., limit set) of a solution to a dynamic system is the outer limit of solution trajectories of the system.[6]: 50–51 Because trajectories become closer and closer to this limit set, the tails of these trajectories converge to the limit set.

- For example, an LTI system that is the cascade connection of several stable systems with an undamped second-order LTI system (i.e., zero damping ratio) will oscillate endlessly after being perturbed (e.g., an ideal bell after being struck). Hence, if the position and velocity of this system are plotted against each other, trajectories will approach a circle in the state space. This circle, which is the Ω limit set of the system, is the outer limit of solution trajectories of the system. The circle represents the locus of a trajectory corresponding to a pure sinusoidal tone output; that is, the system output approaches/approximates a pure tone.

Generalized definitions

editThe above definitions are inadequate for many technical applications. In fact, the definitions above are specializations of the following definitions.

Definition for a set

editThe limit inferior of a set X ⊆ Y is the infimum of all of the limit points of the set. That is,

Similarly, the limit superior of X is the supremum of all of the limit points of the set. That is,

Note that the set X needs to be defined as a subset of a partially ordered set Y that is also a topological space in order for these definitions to make sense. Moreover, it has to be a complete lattice so that the suprema and infima always exist. In that case every set has a limit superior and a limit inferior. Also note that the limit inferior and the limit superior of a set do not have to be elements of the set.

Definition for filter bases

editTake a topological space X and a filter base B in that space. The set of all cluster points for that filter base is given by

where is the closure of . This is clearly a closed set and is similar to the set of limit points of a set. Assume that X is also a partially ordered set. The limit superior of the filter base B is defined as

when that supremum exists. When X has a total order, is a complete lattice and has the order topology,

Similarly, the limit inferior of the filter base B is defined as

when that infimum exists; if X is totally ordered, is a complete lattice, and has the order topology, then

If the limit inferior and limit superior agree, then there must be exactly one cluster point and the limit of the filter base is equal to this unique cluster point.

Specialization for sequences and nets

editNote that filter bases are generalizations of nets, which are generalizations of sequences. Therefore, these definitions give the limit inferior and limit superior of any net (and thus any sequence) as well. For example, take topological space and the net , where is a directed set and for all . The filter base ("of tails") generated by this net is defined by

Therefore, the limit inferior and limit superior of the net are equal to the limit superior and limit inferior of respectively. Similarly, for topological space , take the sequence where for any . The filter base ("of tails") generated by this sequence is defined by

Therefore, the limit inferior and limit superior of the sequence are equal to the limit superior and limit inferior of respectively.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Rudin, W. (1976). Principles of Mathematical Analysis. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 56. ISBN 007054235X.

- ^ Gleason, Andrew M. (1992). Fundamentals of abstract analysis. Boca Raton, FL. pp. 176–177. ISBN 978-1-4398-6481-4. OCLC 1074040561.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Gleason, Andrew M. (1992). Fundamentals of abstract analysis. Boca Raton, FL. pp. 160–182. ISBN 978-1-4398-6481-4. OCLC 1074040561.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Bounded gaps between primes". Polymath wiki. Retrieved 14 May 2014.[unreliable source?]

- ^ "Lebesgue's Criterion for Riemann integrability (MATH314 Lecture Notes)" (PDF). University of Windsor. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-03-03. Retrieved 2006-02-24.

- ^ a b Goebel, Rafal; Sanfelice, Ricardo G.; Teel, Andrew R. (2009). "Hybrid dynamical systems". IEEE Control Systems Magazine. 29 (2): 28–93. doi:10.1109/MCS.2008.931718.

- ^ Halmos, Paul R. (1950). Measure Theory. Princeton, NJ: D. Van Nostrand Company, Inc.

- Amann, H.; Escher, Joachim (2005). Analysis. Basel; Boston: Birkhäuser. ISBN 0-8176-7153-6.

- González, Mario O (1991). Classical complex analysis. New York: M. Dekker. ISBN 0-8247-8415-4.

External links

edit- "Upper and lower limits", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]