The first women's association in Albania was founded in 1909.[5] Albanian women from the northern Gheg region resided within a conservative[6] and patriarchal society. In such a traditional society, the women had subordinate roles in Gheg communities that believe in "male predominance". This is despite the arrival of democracy and the adoption of a free market economy in Albania, after the period under the communist Party of Labour.[7] Traditional Gheg Albanian culture was based on the 500-year-old Kanun of Lekë Dukagjini, a traditional Gheg code of conduct, where the main role of women was to take care of the children and to take care of the home.[6]

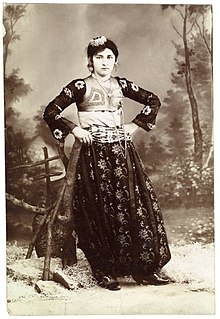

Albanian woman (late 19th century/early 20th century) | |

| General Statistics | |

|---|---|

| Maternal mortality (per 100,000) | 27 (2010) |

| Women in parliament | 35.4%[1] (2021) |

| Women over 25 with secondary education | 81.8% (2012) |

| Women in labour force | 52.0% (2014)[2] |

| Gender Inequality Index[3] | |

| Value | 0.144 (2021) |

| Rank | 39th out of 191 |

| Global Gender Gap Index[4] | |

| Value | 0.787 (2022) |

| Rank | 18th out of 146 |

History

editRights to bear arms

editAccording to a column in The Literary World in 1878, Albanian women were allowed to carry arms.[8]

Traditional Gheg social status

editEdith Durham noted in 1928 that Albanian village women were more conservative in maintaining traditions, such as revenge calling, similar to women in ancient Greece.[9]

Prior to World War II, it was common for some Gheg Albanian women to become "live-in concubines" of men living in mountain areas.[7]

Having daughters is less favoured within the patriarchal society of Gheg Albanians.[7] Due to the giving of greater importance to the desire of having sons than bearing daughters, it is customary that for pregnant Albanian women to be greeted with the phrase "të lindtë një djalë", meaning "May it be a son".[citation needed]

Traditional Lab social status

editThe Labs of Labëria were a patriarchal society.[citation needed] As among the Montenegrins, women in Labëria were forced to do all the drudge work.[10]

Gheg sworn virgins

editIn the past, in family units that did not have patriarchs, unmarried Albanian women could take on the role of the male head of the family by "taking an oath of virginity", a role that would include the right to live like a man, to carry weapons, own property, be able to move freely, dress like men, acquire male names if they wish to do so, assert autonomy, avoid arranged marriages, and be in the company of men while being treated like a man.[6]

Meal preparation

editThe women in central Albania, particularly the women in Elbasan and the nearby regions, are known to cook the sweet tasting ballakume during the Dita e Verës, an annual spring festival celebrated on 14 March. On the other hand, Muslim Albanian women, particularly women from the Islamic Bektashi sect cook pudding known as the ashura from ingredients such as cracked wheat, sugar, dried fruit, crushed nuts, and cinnamon, after the 10th day of matem, a period of fasting.[7]

Women's rights in Albanian politics

editIn the 19th century, Sami Frashëri first voiced the idea of education for women with the argument that if would strengthen society by having educated women to teach their children. In the late 19th century, some urban elite women who had been educated in Western Europe saw a need for more education for women in Albania. In 1891, the first girls' high school was founded in Korçë by Sevasti Qiriazi and Parashqevi Qiriazi and in 1909 they founded the first women's organization in Albania, the Morning Star (Yll’i Mëngesit) with the purpose of raising the rights of women by raising their education level.

The women's movement in Albania was interrupted by the First World War, but resumed when Albania became an independent nation after the war. The Qiriazi sisters founded the organization Perlindja in Korçë, which published the newspaper Mbleta. In 1920, Marie Çoba founded the local women's organization Gruaja Shqiptare in Shkodër, which was followed by several other local organizations with the same name in Korçë, Vlorë and Tiranë.[11]

In 1920 Urani Rumbo and others founded Lidhja e Gruas (the Women's Union) in Gjirokastër, one of the most important feminist organisations promoting Albanian women's emancipation and right to study. They published a declaration in the newspaper Drita, protesting discrimination against women and social conditions. In 1923 Rumbo was also part of a campaign to allow girls to attend the "boy's" lyceum of Gjirokastër.[12] The Albanian women's movement were supported by educated urban elite women who were inspired by the state feminism of Turkey under Kemal Ataturk.[11]

During the reign of Zog I of Albania (r. 1928-1939), women's rights was protected by the state under the national state organization Gruaja Shiqiptare, which promoted a progressive policy and secured women the right to education and professional life and a ban against the seclusion of women in harems and behind veils; equal inheritance rights, divorce, and a ban against arranged and forced marriages as well as polygamy.[13] However, in practice this progressive policy only concerned the cosmopolitan city elite, and had little effect in the lives of the majority of women in Albania.[13]

Limited women's suffrage was granted in 1920, and women obtained full voting rights in 1945.[14] Under the communist government of Albania, an official ideology of gender equality was promoted [15] and promoted by Union of Albanian Women. In the first democratic election after the fall of communism, the number of women deputies in parliament fell from 75 in the last parliament of communist Albania to 9.[16] In a turbulent period after 1991 the position of women worsened.[17][18] There is a religious revival among Albanians which in the case of Muslims sometimes means that women are pushed back to the traditional role of mother and housekeeper.[19] As of 2013 women represented 22.9% of the parliament.[1]

Marriage, fertility, and family life

editThe total fertility rate is 1.5 children born per woman (2015 est.),[20] which is below the replacement rate of 2.1. The contraceptive prevalence rate is quite high: 69.3% (2008/09).[20] Most Albanian women start their families in the early and mid-twenties: as of 2011, the average age at first marriage was 23.6 for women and 29.3 for men.[21]

In some rural areas of Albania, marriages are still arranged, and society is strongly patriarchal and traditional, influenced by the traditional set of values of the kanun.[22] The urbanization of Albania is low compared to other European countries: 57.4% of the total population (2015).[20] Although forced marriage is generally disapproved by society, it is a "well known phenomenon in the country, especially in rural and remote areas," and girls and women in these areas are "very often forced into marriages because of [a] patriarchal mentality and poverty".[23]

Abortion in Albania was fully legalized on December 7, 1995.[24] Abortion can be performed on demand until the 12th week of pregnancy.[25] Women must undergo counseling for a week prior to the procedure, and hospitals that perform abortions are not allowed to release information to the public regarding which women they have treated.[25]

During the government of Enver Hoxha, communist Albania had a natalist policy,[25] leading women to have illegal abortions or to induce them on their own. Eventually the country had the second-highest maternal mortality rate in all of Europe, and it was estimated that 50% of all pregnancies ended in an abortion.[25]

Employment

editDuring the communist era women entered in paid employment in large numbers. The transition period in Albania has been marked by rapid economic changes and instability. The labour market faces many of the problems that are common to most transition economies, such as loss of jobs in many sectors, that were not sufficiently compensated by emerging new sectors. As of 2011, the employment rate was 51.8% for young women, compared to 65.6% for young men.[26]

Education

editAs late as 1946, about 85% of the people were illiterate, principally because schools using the Albanian language had been practically non-existent in the country before it became independent in 1912. Until the mid-nineteenth century, the Ottoman rulers had prohibited the use of the Albanian language in schools.[27] The communist regime gave high priority to education, which included the alphabetization of the population, but also the promotion of socialist ideology in schools.[28] As of 2015, the literacy rate of women was only slightly below that of men: 96.9% female compared to 98.4% male.[20]

Violence against women

editIn recent years, Albania has taken steps to address the issue of violence against women. This included enacting the Law No. 9669/2006 (Law on Measures against Violence in Family Relations) [29] and ratifying the Istanbul Convention.[30]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "Women in Parliaments: World Classification". www.ipu.org. Archived from the original on 28 March 2014. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ "Labor force participation rate, female (% of female population ages 15-64) (modeled ILO estimate) - Data - Table". World Bank. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2021/2022" (PDF). HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORTS. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ "Global Gender Gap Report 2022" (PDF). World Economic Forum. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ De Haan, Francisca; Daskalova, Krasimira; Loutfi, Anna (2006). Biographical Dictionary of Women's Movements and Feminisms in Central, Eastern, and South Eastern Europe: 19th and 20th Centuries. Central European University Press. p. 454. ISBN 978-963-7326-39-4 – via Google Books.

...founders (1909) of the first Albanian women's association, Yll'i mengjezit (Morning Star)

- ^ a b c Bilefsky, Dan. "Albanian Custom Fades: Woman as Family Man". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 February 2013. Retrieved 27 October 2013.

- ^ a b c d Elsie, Robert. "Albania". Advameg, Inc. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 27 October 2013.

- ^ The Literary World: Choice Readings from the Best New Books, with Critical Revisions. James Clarke & Company. 1878. Retrieved 25 December 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ McHardy, Fiona; Marshall, Eireann (2004). Women's Influence on Classical Civilization. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-30958-5. Retrieved 25 December 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ Garnett, Lucy Mary jane and John S. Stuart-Glennie, The Women of Turkey and their Folk-lore, Vol. 2. D. Nutt, 1891.

- ^ a b Musaj, Fatmira; Nicholson, Beryl (1 January 2011). "Women Activists In Albania Following Independence And World War I". Women's Movements and Female Activists, 1918-1923: 179–196. doi:10.1163/ej.9789004191723.i-432.49. ISBN 9789004182769. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ De Haan, Francisca; Daskalova, Krasimira; Loutfi, Anna (2006). Biographical dictionary of women's movements and feminisms in Central, Eastern, and South Eastern Europe: 19th and 20th centuries. G - Reference, Information and Interdisciplinary Subjects Series. Central European University Press. pp. 475–77. ISBN 963-7326-39-1.

- ^ a b "G". Biographical dictionary of women's movements and feminisms in Central, Eastern, and South Eastern Europe: 19th and 20th centuries. Reference, Information and Interdisciplinary Subjects Series. Central European University Press. ISBN 963-7326-39-1.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-10-02. Retrieved 2016-09-30.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Human Rights in Post-communist Albania. Human Rights Watch. 1996. p. 164. ISBN 978-1-56432-160-2.

- ^ Joseph, Suad; Naǧmābādī, Afsāna (2003). Encyclopedia of Women and Islamic Cultures: Family, Law and Politics. BRILL. p. 553. ISBN 978-90-04-12818-7. Archived from the original on 2016-05-21 – via Google Books.

In Albania, there were 73 women out of the 250 deputies in the last communist parliament while in the first post-communist parliament the number of women fell to 9.

- ^ Rueschemeyer, Marilyn (1 January 1998). Women in the Politics of Postcommunist Eastern Europe. Routledge. p. 280. ISBN 9780765602961.

- ^ Brown, Amy Benson; Poremski, Karen M. (2005). Roads to Reconciliation: Conflict and Dialogue in the Twenty-first Century: Conflict and Dialogue in the Twenty-first Century. Routledge. p. 280. doi:10.4324/9781315701073. ISBN 9781315701073. Archived from the original on 9 May 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ Vickers, Miranda; Pettifer, James (1997). Albania: From Anarchy to a Balkan Identity. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-85065-290-8. Archived from the original on 2016-05-15 – via Google Books.

The religious revival among Muslim Albanians also affected women, as conservative family values gained ground and some women were forced back into the conventional roles of homemaker and mother.

- ^ a b c d "The World Factbook". cia.gov. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Select variable and values - UNECE Statistical Database". W3.unece.org. 2016-02-09. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 18, 2015. Retrieved November 17, 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "IRB: Albania: Forced marriages of women, including those who are already married; state protection and resources provided to women who try to avoid a marriage imposed on them (2010-June 2015) [ALB105216.E] | ecoi.net - European Country of Origin Information Network". ecoi.net. Archived from the original on 2016-03-30. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- ^ Aborti – vrasje e fëmijës së palindur (in Albanian) Archived 2013-10-29 at the Wayback Machine Nr. 8045, data 07. 12. 1995, që është mbështetje e nenit të ligjit nr. 7491, të vitit 1991 "Për dispozitat kryesore kushtetuese" me propozimin e Këshillit të Ministrive, miratuar në Kuvendin Popullor të Shqipërisë.

- ^ a b c d "Albania – ABORTION POLICY – United Nations". United Nations. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ "Youth Employment and Migration : Country Brief : Albania" (PDF). Ilo.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- ^ "Albanian "Letërsia e gjuhës së ndaluar"" [The Literature of the Prohibited Language] (PDF) (in Albanian). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-06-05. Retrieved 2010-01-06.

- ^ S.T. Dhamko. Boboshtica. Historie. Boboshtica, 2010 (dorëshkrim). Ff. 139-140.

- ^ "LAW No. 9669 of 18.12.2006 : "ON MEASURES AGAINST VIOLENCE IN FAMILY RELATIONS"". Osce.org. Archived from the original on 2017-05-26. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- ^ Bureau des Traités. "Liste complète". Coe.int. Archived from the original on 2016-02-03. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

External links

edit- Association of Albanian Girls and Women (AAGW)

- Women and Children in Albania, Double Dividend of Gender Equality (PDF), Social Research Centre, INSTAT 2006

- World Vision promotes the equality of women in Albania

- The Women's Program, Open Society Foundation for Albania

- OSCE Presence in Albania, osce.org