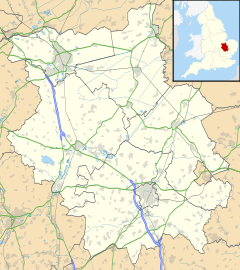

Leighton Bromswold (also known as Leighton) is a small village and civil parish in Cambridgeshire, England.[1] Leighton lies approximately 10 miles (16 km) west of Huntingdon. Leighton is situated within Huntingdonshire which is a non-metropolitan district of Cambridgeshire as well as being a historic county of England. The civil parish of which it is part is called Leighton and in 2001 had a population of 224,[2][3] falling to 210 at the 2011 Census. The parish covers an area of 3,128 acres (1,266 ha).[4]

| Leighton Bromswold | |

|---|---|

| |

Location within Cambridgeshire | |

| Population | 210 (2011) |

| OS grid reference | TL115753 |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Huntingdon |

| Postcode district | PE28 |

| Dialling code | 01480 |

| Police | Cambridgeshire |

| Fire | Cambridgeshire |

| Ambulance | East of England |

| UK Parliament | |

History

editLeighton Bromswold was listed in the Domesday Book of 1086 in the Hundred of Leightonstone in Huntingdonshire; the name of the settlement was written as Lectone.[5] In 1086 there was just one manor at Leighton Bromswold; the annual rent paid to the lord of the manor in 1066 had been £23 and the rent was the same in 1086.[6]

The Domesday Book does not explicitly detail the population of a place but it records that there were 39 households at Leighton Bromswold.[6] There is no consensus about the average size of a household at that time; estimates range from 3.5 to 5.0 people per household.[7] Using these figures then an estimate of the population of Leighton Bromswold in 1086 is that it was within the range of 136 and 195 people.

The survey records that there were 19.5 ploughlands at Leighton Bromswold in 1086.[6] In addition to the arable land, there was 30 acres (12 hectares) of meadows, 10 acres (4 hectares) of woodland and a water mill at Leighton Bromswold.[6]

The tax assessment in the Domesday Book was known as geld or danegeld and was a type of land-tax based on the hide or ploughland. Following the Norman Conquest, the geld was used to raise money for the King and to pay for continental wars; by 1130, the geld was being collected annually. Having determined the value of a manor's land and other assets, a tax of so many shillings and pence per pound of value would be levied on the land holder. While this was typically two shillings in the pound the amount did vary; for example, in 1084 it was as high as six shillings in the pound. For the manor at Leighton Bromswold the total tax assessed was 15 geld.[6]

No church is recorded in the Domesday Book at Leighton Bromswold.

The village has at various times been known as "Lecton" (11th century), "Leghton" and "Leghton upon Brouneswold" (14th century).[4]

Governance

editAs a civil parish, Leighton has a parish council. The parish council is the lowest tier of government in England and is elected by the residents on the electoral roll. A parish council is responsible for providing and maintaining a variety of local services including allotments and a cemetery; grass cutting and tree planting within public open spaces such as a village green or playing fields. The parish council reviews all planning applications that might affect the parish and makes recommendations to Huntingdonshire District Council, which is the local planning authority for the parish. The parish council also represents the views of the parish on issues such as local transport, policing and the environment. The parish council raises a parish precept, which is collected as part of the Council Tax. The parish council consists of five councillors.

Leighton was in the historic and administrative county of Huntingdonshire until 1965. From 1965, the village was part of the new administrative county of Huntingdon and Peterborough. Then in 1974, following the Local Government Act 1972, Leighton became a part of the county of Cambridgeshire.

The second tier of local government is Huntingdonshire District Council which is a non-metropolitan district of Cambridgeshire and has its headquarters in Huntingdon. Huntingdonshire District Council has 52 councillors representing 29 district wards.[8] Huntingdonshire District Council collects the council tax, and provides services such as building regulations, local planning, environmental health, leisure and tourism.[9] Leighton is a part of the district ward of Ellington and is represented on the district council by one councillor.[10][8] District councillors serve for four-year terms following elections to Huntingdonshire District Council.

For Leighton the highest tier of local government is Cambridgeshire County Council which has administration buildings in Cambridge. The county council provides county-wide services such as major road infrastructure, fire and rescue, education, social services, libraries and heritage services.[11] Cambridgeshire County Council consists of 69 councillors representing 60 electoral divisions.[12] Leighton is part of the electoral division of Sawtry and Ellington,[10] represented by one councillor.[12]

Leighton is in the parliamentary constituency of North West Cambridgeshire,[10] and elects one Member of Parliament (MP) by the first past the post system of election. Leighton is represented in the House of Commons by Shailesh Vara (Conservative). Shailesh Vara has represented the constituency since 2005. The previous member of parliament was Brian Mawhinney (Conservative) who represented the constituency between 1997 and 2005.

Geography

editThe parish of Leighton Bromswold contains 3,128 acres (1,266 ha), about half of which is arable and half grass land. Salome Wood is a plantation in the north of the parish, and there are one or two coppices. The soil is heavy and the subsoil is Oxford Clay. The land is undulating and is watered by two brooks, the one flowing from the west through the north and middle part of the parish; and the other, the Ellington Brook, flowing eastward through the southern part of the parish, forms the boundary for short distances. Between these brooks is a high ridge of land known as the Bromswold. On this ridge and also north of the northern brook the land rises to over 200 feet (61 m) above Ordnance datum. From the ridge the land falls to about 100 feet (30 m) to the southern brook and about 70 feet (21 m) to the northern. The population was chiefly engaged in agriculture until the late 20th century.

The village is on the ridge between the two brooks and contains some 17th-century timber framed and plastered houses. The village street lies along the road to Old Weston, with Sheep Street branching off to the north east to Duck End, and Leighton Hill to the south. The church stands at the south-east end of the village, with the Manor Farm, formerly called Church Farm, to the west. South east of the church is the site of the Prebendal Manor House where in the Middle Ages the original village was located. The church is Grade I listed whilst there are seven Grade II listed buildings within the village.

Demography

editPopulation

editIn the period 1801 to 1901 the population of Leighton was recorded every ten years by the UK census. During this time the population was in the range of 246 (the lowest was in 1811) and 455 (the highest was in 1851).[13]

From 1901, a census was taken every ten years with the exception of 1941 (due to the Second World War).

| Parish |

1911 |

1921 |

1931 |

1951 |

1961 |

1971 |

1981 |

1991 |

2001 |

2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leighton | 275 | 242 | 218 | 222 | 207 | 159 | 184 | 208 | 224 | 210 |

All population census figures from report Historic Census figures Cambridgeshire to 2011 by Cambridgeshire Insight.[13]

In 2011, the parish covered an area of 3,128 acres (1,266 hectares)[13] and the population density of Leighton in 2011 was 43 persons per square mile (17 persons per square kilometre).

Landmarks

editThe Leightonstone

editAlongside the Lych Gate of St Mary's Church stands the Leightonstone. It was originally situated to the south east of the Church, where the village originally stood. The Leightonstone is the ancient marker where the Moot Court of the Hundred of Leightonstone gathered to collect taxes and cast judgement of many local issues that were within the jurisdiction of the court.

The Leightonstone was actually sited on the other side of the church but to prevent it becoming lost or damaged it has been moved a few hundred metres to its present location by the church gate together with a commemorative plaque and seating.

War memorial

editThe limestone memorial takes the form of a small medieval-style Latin cross and plinth. The plinth has tracery decorative detail on each corner and flower motif in a band around the top. The names of the nine men from the parish who lost their lives fighting in the First World War are inscribed on the plinth and painted black. The memorial is surrounded by concrete paving and wooden posts with chain link. The memorial was unveiled in 1920 and was the work of Mr Pettit of Godmanchester.

This memorial was a recipient of a grant from the Grants for War Memorials scheme in 2007. In 2009, War Memorials Trust applied for the listing of the war memorial cross. In March, the Trust was advised that the memorial has been listed at Grade II.

The castle gatehouse

editThis interesting earthwork, the site where Sir Gervase Clifton (died 1618) 'began to build a goodly house', is a grass field 600 ft. by 300 ft.enclosed on three sides by large banks averaging 35 ft. across the base, and being 4 ft. 6in. high within the enclosure but 10 ft. outside. On the west side, there is a slightly raised ridge which seems to indicate the line where a bank ran.

At the four corners and almost entirely outside the lines of the banks are curious circular bastions; that at the south-east corner is the best preserved, and is 80 ft. in diameter and its top rises 5 ft. above the bank; those at the other corners appear to have been the same but are not so well preserved. Wherever the edge of the banks and bastions has been cut into a line of broken red bricks, apparently of early date, is exposed, and it would therefore appear that these banks were made by Sir Gervase Clifton, who used the materials of an older house for the purpose.

The bastions were probably merely ornamental features and never intended for purposes of defence. The gatehouse of Sir Gervase Clifton's house, now a private residence, has a moat.

Salome

editJust outside the village are some signs of a hamlet that has almost disappeared. The chapel of Salen is mentioned in 1248 (fn. 72) and in 1299 the question arose as to its being a sanctuary. In 1444 the sum of 16s. 8d. was paid 'pro le riggyng and redyng de la chapell, hall and le chaumbre' at Leighton Bromswold. The site is marked on a map by Thomas Norton (c. 1660) as a square inclosure at the north-west corner of Elecampane Close near the south-west angle of Salome Wood. Near it is a spot marked St Tellin (St Helen) Well. The inclosure is still represented by a slight mound and ditch, and excavations by Dr Garrood disclosed the foundations of the chapel, tiles, glazed pottery, fragments of medieval painted glass, and a coin of Gaucher de Porcein (1314–1329); while a damp depression in the ground nearby may represent the well.

Culture and community

editThe village is home to the Green Man public house which was first licensed in 1650.[14]

The village has a social programme. In July 2011 the village celebrated its charter to run a fair by holding a street party. The charter was given by William, treasurer of King John, who in 1211 obtained a charter for a fair to be held on the Feast of the Invention of the Holy Cross (3 May). There were later two fairs, one on May Day and the other on 24 September. Through the Leighton Bromswold Social Committee a number of other events were held in 2011 including a Safari Supper, Cheese & Wine Evening, trip to the seaside, music festival, Halloween and Bonfire, Senior Citizens' Lunch and Children's Party.

St Mary the Virgin's Church

editThis section may be too long and excessively detailed. (August 2012) |

The Grade I listed church of St Mary, Leighton Bromswold, consists of a chancel (46+3⁄4 by 20+1⁄4 feet), nave (58+1⁄4 by 24 feet), north transept (18+1⁄4 by 20+1⁄4 feet), south transept (17+1⁄2 by 20+1⁄4 feet), west tower (15 by 14 feet) and north and south porches. The walls are of coursed rubble with stone dressings, except the tower, which is faced with ashlar, and the roofs are covered with tiles and lead.

The church is not mentioned in the Domesday Survey (1086). A chancel and an aisled nave were built about 1250, but this chancel was apparently rebuilt about 1310, and large transepts were added to the nave some forty years later. Probably the aisles were partly rebuilt and new windows inserted in them, and perhaps a clerestory added to the nave towards the end of the 15th century. At the beginning of the 17th century the church was in a ruinous condition, and apparently about 1606 a rebuilding was commenced; the south arcade and aisle were pulled down and the south wall of an aisleless nave and south porch built. The work, however, was stopped for lack of funds, and for twenty years the church was 'so decayed, so little, and so useless, that the parishioners could not meet to perform their duty to God in public prayer and praises.' The roofs had fallen in, and the tower was in ruins as were the upper courses of the walls and the nave was roofless.

Chancel

editThe 14th-century chancel has a four-light east window with original jambs, but a late-15th-century depressed four-centred head; on the north side of it a 13th-century capital (now mutilated) has been built in as a bracket. The north wall has two original three-light windows with intersecting tracery in a two-centred head; a late-15th-century three-light window with a depressed four-centred head; and a 13th-century locker with trefoiled head and stone shelf. The south wall has three windows similar to those on the north; a small late-15th-century doorway; a blocked original doorway, only visible inside; a blocked low-side window; a reset 13th-century double piscina having one whole and two half semicircular intersecting arches with interpenetrating mouldings, carried on a central shaft and two detached jamb-shafts with moulded capitals and bases. The 13th-century chancel arch is two-centred, of two chamfered orders, the lower order resting on triple attached corbel-shafts with moulded capitals and modern corbels. The roof is modern, but the moulded principals of 1626 remain. The weathering of the earlier roof remains above the chancel arch.

Nave

editThe nave has, on each side of the chancel arch, the 13th-century respond column of the former arcades; they are semicircular with moulded capitals and bases. The 17th-century north wall has a reset late-15th-century three-light window; a reset 14th-century archway to the porch, of two chamfered orders (probably the old arch between the aisle and transept re-used), the lower order resting on mutilated corbels, reset and altered in the 17th century; and a slight recess close to the west end, as for the inner splay of a window. The 17th-century south wall has features similar to those of the north wall. Both walls have splayed plinths, but those on the south appear to be of rather coarse workmanship and do not extend round the porch, while those on the north are finely wrought and are carried along the east and west walls of the porch.

North transept

editThe 14th-century north transept has a four-light east window with reticulated tracery in a two-centred head. The north wall has a late-15th-century three-light window with a depressed four-centred head. The west wall has, near its northern end, a blocked late-14th-century doorway; and at the southern end the weather stones of the early aisle roof remain. In the north transept are some 17th-century red and yellow glazed flooring tiles.

South transept

editThe 14th-century south transept is similar to the north except that it has no doorway in the west wall. In the east wall is a rectangular shelf-bracket ornamented with ball-flowers and supported on a carved head. The south wall has a trefoiled-headed piscina and a rectangular locker.

Roof

editThe roofs of the chancel, nave and transepts are all of 1626. In the chancel are five trusses with moulded tie beams, moulded and panelled braces and moulded wall-posts with shaped and moulded pendants. On the nave, six bays similar to the chancel with some repairs; transept roofs are similar each of three bays.

The 17th-century north porch has a mid-13th-century north doorway, perhaps the old door of the former aisle in situ; it has a two-centred head of three orders, the two outer orders springing from detached jamb-shafts with moulded capitals and bases and the inner order continuous. The porch has no buttresses, but the plinth of the nave is continued along its east and west walls.

The 17th-century south porch has a mid-13th-century south doorway, almost certainly rebuilt, as it does not seem to be quite on the line of the former aisle wall; it has a two-centred arch of three moulded orders enriched with dog-tooth ornament, and resting on four detached jamb-shafts on each side, having moulded capitals and bases. The east wall has a plain square-headed 17th-century window. The porch has buttresses square at the angles, probably largely of 13th-century material re-used.

Screens

editUnder chancel-arch there is a low screen in two parts with opening in middle, plain lower panels and open upper panels, six on each side, with round arches springing from short turned balusters, moulded top rail and turned knobs over alternate balusters and flanking central opening; c. 1630–40. In south transept modern screen to vestry incorporating eleven bays of arcading probably from one of the stalls or seats, c. 1630–40. In the west tower across north west angle, curved screen or partition of moulded panelling, 16th-century, cornice and door modern now used as a store room.

Twin pulpits

editThe two Pulpits date from 1626, are of oak and of the same general design, set against the two responds of the chancel-arch, each of pentagonal form with a short flight of steps, base having a series of short turned balusters connected by segmental arches and capped by a cornice, the whole continued outwards as a rail to the stairs; upper part of pulpit, each face divided into two bays by turned columns with moulded bases and capitals from which spring segmental arches and the whole finished with an entablature; door similar but with one half-column only, between the bays and with strap-hinges; sounding-board resting on panelled standard at back with two attached pilasters; board finished with an entablature with segmental arches below and turned pendants, boarded soffit with turned pendant in middle.

Benches

editIn the nave there are fourteen benches, upper parts of backs with a series of panels formed by attached half-balusters, with moulded top rail, open ends with turned terminals and curved armrests, supported by turned balusters, c. 1630–40, made up with some modern work. In north transept-six benches generally similar to those in nave but with open arcaded backs formed by segmental arches resting on turned balusters, also one front enclosure of similar design and two benches at east end of nave, c. 1630–40. In chancel-four stalls similar to the benches in the north transept, but with half-balusters attached to the lower panelling, made up with modern work.

Lectern

editThe modern lectern (1903) incorporates some oak balusters and knobs from the staircase of Stow Longa Manor House and was given in memory of Rev. Thomas Ladd who was buried in the churchyard in 1899.

West tower

editIt is generally believed that the west tower was built by James Stewart, 1st Duke of Richmond in 1634, however there is no authority for this. In the July of that year he was just 12 when he succeeded the Dukedom on the death of his father Esmé Stewart. His mother, Katherine Clifton of Leighton Bromswold continued to hold the titles and the lordship until her own death in September 1637. There is also the suggestion that John Ferrar produced a 'ruff draught' for a tower after 1634 with the note "for the finishing of Layton church that he might the better in time provide".

James, Duke of Lennox, Earl of March, Baron Clifton of Leighton Bromswold was at the height of his powers in 1641 and it was probable that the tower was completed before or in that year. On the parapet are the initials 'R.D. 1641', probably made by Richard Drake, a long-standing friend of Nicholas Ferrar. In 1655 it was recorded that "Only the steeple could not be compassed wch afterwards the most Noble, Religious, worthy good Duke of Lenox did perform at his own proper cost & charges, to the Memorial of his Honor."

The tower is of three stages finished with a modillioned cornice between the buttresses, an embattled parapet and angle pedestals, supporting obelisks with ball-terminals. The two-centred tower-arch is of two classically moulded orders springing from square responds with moulded imposts. The west window is of two coupled lights divided and flanked by plain pilasters and with round heads, moulded archivolts and imposts; the west doorway is flanked by plain pilasters with moulded capitals, and has a half-round moulded arch with a plain keystone; above the doorway is a plain tablet.

The second stage has in the west wall a square-headed window with a moulded stone architrave. The bell-chamber has in each wall a double window similar to, but larger than, the west window of the ground-stage; above each pair of windows is a lozenge-shaped panel.

The stairs to the belfry are at the south-west corner. In the north-eastern corner of the tower is a modern disused brick chimney. On the tower floor is the matrix of a 15th-century monumental brass with the figure of a man and an inscription plate. In 1552 there were four bells and a sanctus bell.

Bells

editWithin the west tower are five bells dating 1641 and 1720. The bells were rehung, in a new frame, in 1902 by Barwell of Birmingham and a brass plaque commemorating the event is on the north wall of the nave. The biggest bell weighs 21hundredweight 1 quarter and 4 pounds making it the 3rd heaviest ring of 5 bells in the country. They hang in a 6 bell frame (6.1) with space for a new treble. More info: http://dove.cccbr.org.uk/detail.php?searchString=Leighton+Bromswold&Submit=+Go+&DoveID=LEIGHTONBR

Miscellaneous

editBrackets in chancel east wall, in form of moulded capital, late-13th-century, now cut back to wall-face. In south transept east wall, rectangular shelf with 'ball-flower' ornament and a carved head below, early-14th-century

Communion Table: with turned legs, moulded top rails with shaped brackets, plain lower rails, c. 1630–40, top modern.

There are two chairs in the chancel with moulded and twisted legs, front rail, and back-uprights, of c. 1700. A 16th-century chest is in the north transept and is plain with coped lid, two locks, iron straps and three strap¬hinges, all terminating in fleurs-de-lis.

The font is made up of two 13th-century circular moulded capitals and a piece of circular shaft. The cover is largely modern, but has a 17th-century ball on the top and a Victorian mounting.

In the nave the north and south doorways, the doors are twinned, each of two leaves with moulded panels and nail-studded framing; both doors set in moulded framing, with panelling above, mid-17th-century, partly repaired.

The Lockers in chancel north wall, with rebated jambs and trefoiled head, stone division or shelf, late 13th¬century. In south transept south wall, rectangular, with chamfered and rebated reveals, 14th-century.

In chancel, on the south wall, there is a double piscinae. with two-centred arches the moulding continued to form an intersecting arcade, free shaft to each jamb and in middle, with moulded capitals and bases, shelves within the recess, at level of abaci of side-shafts, two multifoiled drains, mid-13th-century, reset. In south transept in the south wall, there is a recess with trefoiled head and round drain, 14th-century.

Rainwater heads

editRainwater-heads are in lead. On north and south walls of chancel there are four, three with embattled tops and painted decoration, curved junction with down-pipes, on one of which is a fleur-de-lis; one head on south side elaborately shaped, with enriched cornice and cresting, the date 1632, and strap-work ornament on the flanges, junction with down-pipe enriched with acanthus ornament, down-pipe with strap-work ornament and enriched straps with three crests. On the north wall of north transept two shaped heads with embattled tops, the two heads bearing together the date 1634. On north wall of nave, head with arabesque ornament and painted decoration; on south wall, with rounded and moulded head. On south wall of south transept, two similar to those on north transept, but with painted decoration and no date, all 17th-century.

Altar-tombs

editIn the north transept is an alabaster altar-tomb with mutilated effigies of Sir Robert Tyrwhitt, who died on 10 May 1572 in Leighton Bromswold, and Elizabeth, his last wife who died in 1578. Altar-tomb of alabaster, south side divided into three bays by ornamental pilasters, shield in middle bay with arms three tirwhitts for Tyrwhitt quartering a chief indented, the whole impaling a lion rampant with a forked tail and a border, figures of daughter and two swaddled infants in side bays; similar pilasters west end of tomb, forming two bays each with a shield bearing the quarterly coat above and the impaled coat; on tomb, recumbent effigies of man and wife, man in plate-armour with head on mantled helm and lion at feet, legs of man missing; effigy of wife in French cap, long cloak,

Also in the north transept, further west, is a mutilated alabaster effigy of probably Katherine, the 4th daughter of Sir Robert and Elizabeth, and wife of Sir Henry D'Arcy, died 1567, head on two cushions, hands broken, modern altar-tomb with old alabaster plinth, mid- to late-16th-century.

Lying loose, close to these monuments, is a broken stone crest. There is also a monument of Sir Robert Tyrwhitt and his wife Elizabeth Oxenbridge in Bigby church, Lincolnshire, dated 1581, which unlike the monument in Leighton church, included effigies of all his twenty-two children.

Worshipful Company of Dyers

editIn the Church box a letter was discovered, dated 1947, confirming that the effigies were of Sir Robert Tyrwhitt, the first benefactor of the Worshipful Company of Dyers, and that if ever the effigies could be restored, the Dyers Company would be interested to help. A letter was despatched appealing to them for help and telling them of the efforts of this small parish of 220 souls, including all denominations. The Worshipful Company of Dyers very generously offered to relieve the village of its financial burden and pay off the remainder of the money by Deed of Covenant.

There is engraved graffiti scratching on the tower parapet, R.D. 1641; on doorway of bell-chamber, W.H. R.I. 1666; on wall of second stage, E.S. 1653.

There are the following monuments: in the chancel, to the Rev. Thomas Ladds, vicar, died 1899; in the nave, to Ernest Cook, died 1917, Wilfred Barwell, died 1918; Lewis Robert Jellis, died 1933; in the south transept, to Hugh Brawn, died 1917; in the tower, floor slab to William Chapman, died 1687.

Herbert's restoration

editRev. George Herbert (1593–1633) was presented with the Prebendary of Leighton in 1626, whilst he was a don at Trinity College, Cambridge. He was not even present at his institution as prebend as it is recorded that Peter Walker, his clerk, stood in as his proxy. In the same year that his close Cambridge friend Nicholas Ferrar was ordained Deacon in Westminster Abbey by Bishop Laud on Trinity Sunday 1626 and, two miles down the road from Leighton Bromswold, founded the Little Gidding community.

No religious offices had been said in the church for over twenty years, Izaak Walton wrote - 'so decayed, so little, and so useless, that the parishioners could not meet to perform their duty to God in public prayer and praises'. Although during that time it is recorded that John Barber MA in 1607 and Maurice Hughes MA in 1623 were described as taking up their duties as vicars of St Mary's Leighton Bromswold and it probable at this it is said that the Lord Lennox's barn was used for divine service.

Permission from the Crown had been obtained by the previous incumbent to re-build the church at a cost of £2,000 (approximately £1,000,000 in today's money)

To raise this money was too daunting so George Herbert asked Nicholas Ferrar to help rebuild the ruined church but Nicholas was fully occupied with his community, so he suggested that his brother, John Ferrar, should supervise the rebuilding whilst Herbert, for his part, should try and raise the money amongst his influential friends. Which he achieved. £50 from William, Earl of Pembroke; £200 from Catherine Clifford, daughter of Lord Clifton of Leighton Bromswold; some money from Lord Manchester and Lord Bolingbroke and also from Henry Herbert, George's brother, Donations, small and great, came from here and there. The actual rebuilding was supervised by John Ferrar, and Arthur Wodenoth, a wealthy gold merchant, who was also a subscriber, acted as Treasurer and during John Ferrar's absence as his deputy.

It is recorded later (by John Ferrar in 1632) that there were 18 masons and labourers and 10 carpenters at work during the reconstruction and that 'all was finished inside and out, not only to ye Parishioners own much comfort and joy, but to the admiration of all men, how such a structure should be raysed and brought to pass by Mr Herbert'.[citation needed]

Shortly after 1626 the work was completed by pulling down the north arcade and aisle and building the north wall of the new aisleless nave and the north porch; he re-roofed the whole church and put in the pulpit, reading desk, dwarf screen and seating.

In 1630, three years before his death, he entered priesthood and took up his duties as rector of the little parish of Fugglestone St Peter with Bemerton St Andrew, near Salisbury in Wiltshire. It is probable that George Herbert never saw the results of his efforts.

Perhaps a fitting epitaph for the faithful of St Mary's and George Herbert are the words written in Izaac Walton's book on Herbert's life (1670). He said: "Allow that Herbert in the body never looked on Leighton Church, never worshipped God in its aisles; Leighton Church was very dear to Herbert's heart: it was hallowed by his prayers, it was washed by his tears. It is ever to be remembered as incensed by his memory."

Walton's Lives 1796

editFrom a note to a 1796 edition of Walton's Lives, quoted in H. B. Maling, 'Leighton Bromswold, the Church and Lordship'.

It appears from a recent survey of this church, that the reading desk is on the right hand in the nave, just as you enter the chancel, and that is height is seven feet, four inches; and that the pulpit is on the left hand, and exactly of the same height. They are both pentagonal. The church is at present paved with bricks; the roofs bother of the church and chancel tiles, and not under drawn or ceiled. There are no communion rails; but, as you advance to the communion table you ascend three steps. The windows are large and handsome, with some small remnants of painted glass. The seats and pews both in the nave, the cross-aisles, and the chancel, somewhat resemble the stalls in cathedrals, but are very simple, with little or no ornament, nearly alike, and formed of oak. It was evidently the intention of Mr Herbert that in his church there should be no distinction between the seats of the rich and those of the poor. During Divine Service the men have from time immemorial been accustomed to sit on the south side of the Nave, and the women on the north side. In the cross-aisles the male servants sit on the south side, and the female servants on the north side.

1868 survey

editIn October 1868 Ewan Christian surveyed the church on behalf of the Commissioners and commented that

The interior of the church is well white-washed as to its walls, but being open to the tiles has a bare and barn like look. The tower is blocked off by a gallery, which greatly damages the internal appearance. The nave and transepts still retain the benches of the 17th century, but the wood floors under these are to some extent decayed, and the benches themselves need repair. The chancel was also benched in the same way, but a few years ago the benches were removed into the transepts and large square pews of high deal framing erected in their stead. They are very unsightly and ought to be removed. The pulpit and the desk are also of the 17th century, each of the same height and each has a sounding board over head. The chancel has a plain balustrade rail comparatively modern and both ugly, and wrongly placed.

As a result, the paving in the chancel was renewed, the square chancel pews being converted into benches with some modern material, (this can clearly be seen in the front westward chancel bench, where the turnings and woodwork are of similar, but different design and texture) and wooden floors modified with some new woodwork into its current configuration and the benches were removed into the transepts. Work was also carried out in the nave and transepts, improving the wooden floors and benches and providing some new ones, also new steps and paving for the passage, restuccoing walls and repairing the old pulpits and desk as well as removing the gallery and opening the tower, restoring old doors and the gate.

The church was restored in 1870 as a result of Christian's survey. The children's pews at the west end of the nave were installed in 1870 as a result of a request from the vicar Rev. Thomas Ladd at a cost of £18 at which time the font was mounted.

The original globe electric lights were installed in June 1900 (they were dismantled and are currently stored in the north west of the tower) and replaced in the 1990s by sodium industrial lighting which remains to this day, at the same time the heating system was replaced.

Originally it was headed by wood burner in the west tower drafting hot air down the centre of the nave where the cast iron grilling can still be seen. Later it was converted to low-wattage oil-filled electric pipe heating under selected benches and finally with medium-wavelength infra-red heaters in the chancel only. Currently there is no heating in the church.

In 1914 the tie beam in the chancel was cut out and replaced by an iron rod, drawing by Inskipp Ladds, but in 1914 the vicar, Rev. John Cooper, commented that the tie beam is 'a real eyesore disfiguring as it does the east window and hiding the tracery.' An additional tie beam was added across the east face of the west tower.

Modern upkeep

editIn 1961 the Ely Diocesan Board asked for a quinquennial inspection report to be prepared by John Gedge, architect. This was presented to the parochial church council, and the estimated cost was £8,000. The architect, stressing that such a large amount from such a small parish would be impossible to raise, suggested the more important items of roof and gutters should have top priority.

One member of the parochial church council wrote to the Church Commissioners asking if St Mary's, Leighton Bromswold had a lay rector. To this query, came answer that they held this office and were solely responsible for the repair and upkeep of the chancel. This part of the restoration was carried out for the Church Commissioners by John Allen & Co., Brampton at the figure of £5,500. The architect, Major Gedge, set the target figure of £3,000 to cover the remainder of the work on the restoration of the church.

The Leighton Village Fund for Church Restoration was opened in 1962. On 28 July 1962 a barbecue dance was staged in the village field and a fete down the village street added another £358. The following year, 1963, another barbecue dance, in a barn and another fete added a further £225 and in 1964 another £199 was made from a fete. Altogether, with donations and other efforts, a total of £901 was made.

The Historic Churches Preservation Trust donated £500, Church Commissioners gave £50. The two Restoration Appeal Funds were closed in September 1964 having reached the target of £3,000.

During the winter of 1964, a farmer sent his men and they removed from the churchyard an estimated 100 tons of soil so that the level of the ground outside the church is at least 6 inches lower than the floor inside. A 24-inch-wide trench, 1+1⁄2 to 2 feet deep, was dug all round the church and was refilled with 95 tons of gravel to assist drainage and prevent damp rising in the church. The old drainage system was exposed and renewed where necessary. The gravel was given and carted from Thrapston by the farmer and also red bank drainage tiles.

On 3 June 1965, the Bishop of Ely, lead a thanksgiving service to commemorate the completion of the work with the Choir of St John's, Cambridge and the Ely Diocesan Bellringers. It was televised by BBC TV.

Lych gate

editThe lych gate was built in 1893. It was dedicated to the memory of George Smith, sometime churchwarden and buried in the churchyard, by his widow, Margaret in 1909.

Clock

editOriginally, a provision was made on all four sides of Leighton church tower for square clock faces set lozenge-style, recalling similar clocks on the St Gregory Tower at St Paul's and the western turret at Covent Garden (neither of which are still in existence). There are additional similarities in the design of the west tower to these two churches, in particular the parallel windows of the ringing chamber, though there is no evidence to suggest that there was any formal connection. However, as built, the west tower has a single clock face on the west face of the tower.

In 1977 the church clock winding system was electrified at a cost of £365. This was to save someone climbing up narrow winding stone steps to the Clock Tower floor and winding up two sets of mechanisms, striking and timing, 5 times in fourteen days. The necessary wiring was installed in May 1976 enabling the work to commence.

For the clock, the work consisted of a RPH50C motor and Junior winder weighing approximately 16 pounds with overload protection and regulator. A 16-tooth split chain and 10 feet of one-half-inch pitch roller chain with idler and chain adjuster. For the strike, the installation consisted of a RPH50AC motor and Mark II winder weighing approximately 40 pounds with overload protection and regulator. A 16-tooth split chain and 35 feet of one-half-inch pitch roller chain with idler and chain adjuster. The clock was also cleaned and repainted with the internal dial re-lacquered. The work was carried out by the inventor of the system, David Gamble of Eaton Socon and consists of a small electric motor clamped to weights and geared with sprockets onto a continuous chain. As the weight operates the clock mechanism by pulling downwards, the electric motor monkey is climbing up the chain at the same speed, so that the weight never has to be cranked back to the top.

Chantry

editThere was a chantry at Leighton Bromswold apparently in the church, which was founded by Master Gilbert Smith, Archdeacon of Northampton, and endowed with a pension payable by St Andrew's Priory, Northampton.

The church's gatehouse was built in the 15th century and is the only part of a mansion designed by John Thorpe for the Duke of Lennox that was actually completed.[4]

Notable residents

editNicholas Grimald (1519–1562), the poet, was supposed to have been born in Leighton Bromswold.

The Spanish Armada Muster Call of Captain Wanton's men happened on 2 August 1588; those mustered included two pikemen, Richard Clarke and Nick Colton, both from Leighton Bromswold.

References

edit- ^ Ordnance Survey: Landranger map sheet 142 Peterborough (Market Deeping & Chatteris) (Map). Ordnance Survey. 2012. ISBN 9780319229248.

- ^ A Vision of Britain Through Time : Huntingdon Rural District

- ^ Office for National Statistics : Census 2001 : Parish Headcounts : Huntingdonshire

- ^ a b c "Leighton Bromswold. A History of the County of Huntingdon: Volume 3 (1936), pp. 86–92". Victoria County History.

- ^ Ann Williams; G.H. Martin, eds. (1992). Domesday Book: A Complete Translation. London: Penguin Books. p. 1370. ISBN 0-141-00523-8.

- ^ a b c d e J.J.N. Palmer. "Leighton Bromswold". Open Domesday. Anna Powell-Smith. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ^ Goose, Nigel; Hinde, Andrew. "Estimating Local Population Sizes" (PDF). Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ a b "Huntingdonshire District Council: Councillors". www.huntingdonshire.gov.uk. Huntingdonshire District Council. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ "Huntingdonshire District Council". www.huntingdonshire.gov.uk. Huntingdonshire District Council. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ a b c "Ordnance Survey Election Maps". www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk. Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ "Cambridgeshire County Council". www.cambridgeshire.gov.uk. Cambridgeshire County Council. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ a b "Cambridgeshire County Council: Councillors". www.cambridgeshire.gov.uk. Cambridgeshire County Council. Archived from the original on 22 February 2016. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ^ a b c "Historic Census figures Cambridgeshire to 2011". www.cambridgeshireinsight.org.uk. Cambridgeshire Insight. Archived from the original (xlsx - download) on 15 February 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ "Green Man, Leighton Bromswold".