The languages of Singapore are English, Chinese, Malay and Tamil, with the lingua franca between Singaporeans being English, the de facto main language. Singaporeans often speak Singlish among themselves, an English creole arising from centuries of contact between Singapore's internationalised society and its legacy of being a British colony. Linguists formally define it as Singapore Colloquial English.[1] A multitude of other languages are also used in Singapore. They consist of several varieties of languages under the families of the Austronesian, Dravidian, Indo-European and Sino-Tibetan languages. The Constitution of Singapore states that the national language of Singapore is Malay. This plays a symbolic role, as Malays are constitutionally recognised as the indigenous peoples of Singapore, and it is the government's duty to protect their language and heritage.[a]

| Languages of Singapore | |

|---|---|

A construction danger sign in Singapore's four official languages: English, Chinese (Mandarin), Malay and Tamil | |

| Official | English, Chinese, Malay, Tamil |

| National | Malay |

| Main | English (de facto) Malay (de jure) |

| Vernacular | Singapore English (formal), Singlish (informal) |

| Minority | Baba Malay, Bazaar Malay, Cantonese, Hokkien, Hainanese, Hakka, Teochew, Indonesian, Javanese, Japanese, Punjabi, Malayalam, Arabic |

| Immigrant | Korean, Farsi, Armenian, Bengali, Hebrew, Hindustani, Telugu, Thai, Vietnamese, Yiddish |

| Foreign | Dutch, French, German, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish, Filipino |

| Signed | Singapore Sign Language |

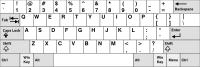

| Keyboard layout | |

The three languages other than English were chosen to correspond with the major ethnic groups present in Singapore at the time: Mandarin had gained status since the introduction of Chinese-medium schools; Malay was deemed the "most obvious choice" for the Malay community; and Tamil for the largest Indian ethnic group in Singapore, in addition to being "the language with the longest history of education in Malaysia and Singapore".[2] In 2009, more than 20 languages were identified as being spoken in Singapore, reflecting a rich linguistic diversity in the city.[3][4] Singapore's historical roots as a trading settlement gave rise to an influx of foreign traders,[5] and their languages were slowly embedded in Singapore's modern day linguistic repertoire.

In the early years, the lingua franca of the island was Bazaar Malay (Melayu Pasar), a creole of Malay and Chinese, the language of trade in the Malay Archipelago.[6] While it continues to be used among many on the island, especially Singaporean Malays, Malay has now been displaced by English. English became the lingua franca due to British rule of Singapore,[5] and was made the main language upon Singaporean independence. Thus, English is the medium of instruction in schools, and is also the main language used in formal settings such as in government departments and the courts. According to Singaporean President Halimah Yacob during her 2018 speech, "Through the education system, we adopted a common working language in English."[7]

Hokkien (Min Nan) briefly emerged as a lingua franca among the Chinese,[5] but by the late 20th century it had been eclipsed by Mandarin. The Government promotes Mandarin among Singaporean Chinese people, since it views the language as a bridge between Singapore's diverse non-Mandarin speaking groups, and as a tool for forging a common Chinese cultural identity.[8] China's economic rise in the 21st century has also encouraged a greater use of Mandarin. Other Chinese varieties such as Hokkien, Teochew, Hakka, Hainanese and Cantonese have been classified by the Government as "dialects", and language policies and language attitudes based on this classification and discouragement of usage in Non-Mandarin Chinese or "Chinese dialects" in official settings and television media have led to a decrease in the number of speakers of these varieties.[9] In particular, Singapore has its own lect of Mandarin; Singaporean Mandarin, itself with two varieties, Standard and Colloquial or spoken. While Tamil is one of Singapore's official and the most spoken Indian language, other Indian languages are also frequently used by minorities.[10]

Almost all Singaporeans are bilingual since Singapore's bilingual language education policy promotes a dual-language learning system. Learning a second language has been compulsory in primary schools since 1960 and secondary schools since 1966.[11] English is used as the main medium of instruction. On top of this, most children learn one of the three official languages (or, occasionally, another approved language) as a second language, according to their official registered ethnic group. Since 1 January 2011, if a person is of more than one ethnicity and their race is registered in the hyphenated format, the race chosen will be the one that precedes the hyphen in their registered race.[12]

English as the de facto main language of Singapore

editAlthough Malay is de jure national language, Singapore English is regarded de facto as the main language in Singapore,[13] and is officially the main language of instruction in all school subjects except for Mother Tongue lessons in Singapore's education system.[14] It is also the common language of the administration and is promoted as an important language for international business.[15] Spelling in Singapore largely follows British conventions, owing to the country's status as a former Crown Colony.[16] English is the country's default lingua franca despite the fact that four languages have official status.[17]

Under the British colonial government, English gained prestige as the language of administration, law and business in Singapore. As government administration increased, infrastructure and commerce developed, and access to education further catalysed the spread of English among Singaporeans.

When Singapore gained self-government in 1959 and independence in 1965, the local government decided to keep English as the main language to maximise economic benefits. Since English was rising as the global language for commerce, technology and science, promotion of its use in Singapore would expedite Singapore's development and integration into the global economy.[18]

Furthermore, the switch to English as the only medium of instruction in schools aided in bridging the social distance between the various groups of ethnic language speakers in the country. Between the early 1960s to the late 1970s, the number of students registering for primarily English-medium schools leapt from 50% to 90%[19] as more parents elected to send their children to English-medium schools. Attendance in Mandarin, Malay and Tamil-medium schools consequently dropped and schools began to close down. The Chinese-medium Nanyang University also made the switch to English as the medium of instruction despite meeting resistance, especially from the Chinese community.[20]

There has been a steep increase in the use of the English language over the years.[21] Singapore is currently one of the most proficient English-speaking countries in Asia.[22] Then Education Minister, Ng Eng Hen, noted a rising number of Singaporeans using English as their home language in December 2009. Of children enrolled in primary school in 2009, 60% of the Chinese and Indian pupils and 35% of the Malay pupils spoke predominantly English at home.[23]

| English | Mandarin | Chinese Dialects |

Malay | Tamil | Others | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | — | — | ||||

| 2000 | ||||||

| 2010 | ||||||

| 2015[25] | ||||||

| 2020[26] |

Singlish

editSinglish is an English-based creole language with its own consistent rules and phonology widely used in Singapore.[27] However, usage of this language is discouraged by the local government, which favours Standard English.[28] The Media Development Authority does not support using Singlish in television and radio advertising.[29]

According to a 2018 study by the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS), only 8% of Singaporeans identify with Singlish as their primary language, compared to the one-third that identify with English and another 2% with their official mother tongue.[30] Both survey waves, in 2013 and 2018, conducted showed that about half of all respondents reported being able to speak Singlish "well" or "very well". Younger respondents (18–25 years old) reported greater proficiency than older respondents (65+ years old).[31]

Over the years, the use of Singlish has become more widespread, with a greater number of people adopting the language both out of a sense of identity and cultural importance. Some even view that it identifies them as uniquely Singaporean.[32][33]

Chinese

editAccording to the 2020 population census, Mandarin and other varieties of Chinese are the second most common languages spoken at home. They are used by 38.6% of the population.[34]

The table below shows the change in distribution of Mandarin and other Chinese varieties, as well as English, as home languages of the resident Chinese population of Singapore over the decades. From 1990 to 2010, it can be observed that the percentage of the population which speaks English and Mandarin increased, while the percentage of those who speak other Chinese varieties has collapsed and is now limited mainly to the elderly.[10] From 2010, the number of Mandarin speakers has also declined in favour of English.[34]

English is starting to displace Mandarin among the new generation of Singapore Chinese due to long term effects of the dominant usage of English in most official settings over Mandarin, the dominant usage of English as the medium of instruction in Singapore schools, colleges and universities, and the limited and lower standards of local mother education system over the years in Singapore.[citation needed]

| Total | English | Mandarin | Other Chinese varieties | Others | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | ||

| 1990 | 1,884,000 | 363,400 | 566,200 | 948,100 | 6,400 | ||||

| 2000 | 2,236,100 | 533,900 | 1,008,500 | 685,800 | 7,900 | ||||

| 2010 | 2,527,562 | 824,616 | 1,206,556 | 485,765 | 10,625 | ||||

| 2015 | |||||||||

| 2020 | |||||||||

Standard Mandarin

editStandard Mandarin, often simply known as Chinese, is the designated mother tongue or 'ethnic language' of Chinese Singaporeans, at the expense of the other Chinese varieties.

In 1979, the government heavily promoted Mandarin through its "Speak Mandarin" campaign. The Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew stated that Mandarin was chosen to unify the Chinese community with a single language.[36] With the rising prominence of Mandarin in Singapore at that time,[2] politicians such as Lee theorised that it might overtake English,[37] despite strong evidence to the contrary.[38] From the 1990s, with the perceived increase in commerce and trade possibilities with Mainland China, the Singaporean government promoted Mandarin as a language with high economic advantage and value.[39] Today, Mandarin is generally seen as a way to maintain a link to Chinese culture.[40]

Other Chinese varieties

editOther Chinese varieties also have a presence in Singapore. Amongst them, Hokkien used to be an unofficial language of business until the 1980s.[41] Hokkien was also used as a lingua franca among Chinese Singaporeans, and also among Malays and Indians to communicate with the Chinese majority.[5] As of 2012, according to demographic figures, the five main Chinese linguistic groups in Singapore are Hokkien (41.1%), Teochew (21.0%), Cantonese (15.4%), Hakka (7.9%) and Hainanese (6.7%), while Hokchew/Hokchia (Fuzhou dialect), Henghua (Puxian Min), and Shanghainese have smaller speaker bases. Other than Mandarin, the two most commonly spoken varieties of Chinese are Hokkien which is the dominant dialect and Cantonese, both of which are mainly spoken among the older generation. Teochew is being replaced by Hokkien, while other Chinese varieties are increasingly less commonly heard nowadays.[35][39][42]

Written Chinese

editTraditional Chinese characters were used in Singapore until 1969, when the Ministry of Education promulgated the Table of Simplified Characters (simplified Chinese: 简体字表; traditional Chinese: 簡體字表; pinyin: jiǎntǐzìbiǎo), which while similar to the Chinese Character Simplification Scheme of the People's Republic of China had 40 differences. In 1974 a new Table was published, and this second table was revised in 1976 to remove all differences between simplified Chinese characters in Singapore and China.[43] Although simplified characters are currently used in official documents, the government does not officially discourage or prohibit the use of traditional characters. Hence, traditional characters are still used in signs, advertisements and Chinese calligraphy, while books in both character sets are available in Singapore.

Malay

editMalay is the national language of Singapore and one of its official languages. It is written using a version of the Roman script known as Rumi.[44] It is the home language of 13% of the Singaporean population.[45] Malay is also the ceremonial national language and used in the national anthem of Singapore,[46] in citations for Singapore orders and decorations and military foot drill commands, mottos of several organisations, and is the variety taught in Singapore's language education system.[citation needed] Linguistically, the vernacular Malay dialect of Singapore is similar to even derived from that of Johore, but with a possible Javanese substrate "much influenced by its proximity to Java",[47] as well as having a flap rhotic consonant (/ɾ/).[48]

Historically Malay was written in the Jawi script, based on Arabic. Under the British and Dutch Malay began to be written in Rumi. Efforts to create a standardised spelling for Malaya and Singapore emerged in 1904 by colonial officer Richard Wilkinson. In 1910, the Malay of the Riau Islands was chosen by the Dutchman van Ophuijsen as the dialect for his book "Malay Grammar", intended for Dutch officials, standardising Rumi usage in Dutch territories.[49] In 1933, grammarian Zainal Abidin bin Ahmad made further changes to Rumi as used in Malaya and Singapore.[50] Many Chinese immigrants who spoke Malay were supporters of British rule, and purposely used Rumi when writing newspapers or translating Chinese literature. Printing presses used by colonial officials and Christian missionaries further spread Rumi, while Jawi was mostly written by hand. The transition to Rumi changed the Malay language due to the influence of English grammar.[49] In 1972, Malaysia and Indonesia reached an agreement to standardise Rumi Malay spelling.[50] Singaporean Malays still learn some Jawi as children alongside Rumi,[51] and Jawi is considered an ethnic script for use on Singaporean Identity Cards.[52]

Prior to independence, Singapore was a centre for Malay literature and Malay culture. However, after independence, this cultural role declined. Singapore is an observer to the Language Council for Brunei Darussalam-Indonesia-Malaysia which works to standardise Malay spelling, however it has not applied to be a member. It nonetheless applies standardisations agreed to in this forum, and follows the Malaysian standard when there are disagreements.[53] Standards within the country are set by the Malay Language Council of Singapore. There are some differences between the official standard and colloquial usage. While the historical standard was the Johor-Riau dialect, a new standard known as sebutan baku (or bahasa melayu baku) was adopted in 1956 by the Third Malay language and Literary Congress. This variation was chosen to create consistency between the written word and the spoken pronunciation. However, implementation was slow, with Malaysia only fully adopting it in the educational system in 1988, with Singapore introducing it at the primary school level in 1993. Despite expanding use in formal education, it has not replaced the Johor-Riau pronunciation for most speakers.[54] The artificial creation of the accent means there are no truly native speakers, and the pronunciation is closer to Indonesian than it is to Johor-Riau. There has also been cultural resistance, with accent differences between older and younger generations leading to questions surrounding Malay cultural identity. This question was further sharpened by Malaysia dropping sebutan baku in 2000, returning to the traditional use of Johor-Riau.[55]

While the official Mandarin and Tamil mother tongues often do not reflect the actual language spoken at home for many, Malay is often the language spoken at home in Singaporean Malay households. Due to this, and strong links between the language and cultural identity, the Singaporean Malay community has retained stronger usage of their mother tongue than others in the country. Nonetheless, there has been some shift towards English, with use of Malay as the primary language at home dropping from 92% to 83% between 2000 and 2010.[56] This reflects a broader shift in Singapore, with English replacing Malay as the lingua franca throughout the late 20th century.[57]

Other varieties that are still spoken in Singapore include Bazaar Malay (Melayu Pasar), a Malay-lexified pidgin, which was once an interethnic lingua franca when Singapore was under British rule.[6][58] Another is Baba Malay, a variety of Malay Creole influenced by Hokkien and Bazaar Malay and the mother tongue of the Peranakans,[6] which is still spoken today by approximately 10,000 Peranakans in Singapore.[59] Other Austronesian languages, such as Javanese, Buginese, Minangkabau, Batak, Sundanese, Boyanese (which is a dialect of Madurese) and Banjarese, are also spoken in Singapore, but their use has declined. Orang Seletar, the language of the Orang Seletar, the first people of Singapore and closely related to Malay is also spoken near the Johor Strait, between Singapore and the state of Johor, Malaysia.

Tamil

editTamil is one of the official languages of Singapore and written Tamil uses the Tamil script. According to the population census of 2010, 9.2% of the Singaporean population were of Indian origins,[60] with approximately 36.7% who spoke Tamil most frequently as their home language.[10] It is a drop from 2000, where Tamil-speaking homes comprised 42.9%.[10] On the other hand, the percentage of Indian Singaporeans speaking languages categorised under "others" have increased from 9.7% in 2005 to 13.8% in 2010.[10] Meanwhile, the percentage of the total population speaking Tamil at home has remained steady, or has even slightly risen over the years, to just above 4%, due to immigration from India and Sri Lanka.

There are a few reasons that contribute to Tamil's declining usage. Historically, Tamil immigrants came from different communities, such as Indian Tamils and Sri Lankan Tamils which spoke very different dialects, dividing the potential community of Tamil speakers. The housing policy of Singapore, with ethnic quotas that reflect national demographics, has prevented the formation of large Tamil communities. The Tamil taught in education is a deliberately pure form, that does not reflect and therefore does not reinforce Tamil as it is used in everyday life. Tamil is usually replaced by English, which is seen as providing children with greater opportunities in Singapore and abroad.[61] The top-down Tamil language purism as dictated by the Ministry of Education Curriculum Planning and Development Division restricts language development, disallowing loanwords. However, the language policy is supported by Tamils, likely due to contrast with that of neighbouring Malaysia where Tamil has no status.[62]

Tamil names are commonly used in countries like India, Sri Lanka, and Singapore. In these countries, Tamil people preserve their heritage and culture through their names.[63]

Apart from Tamil, some of the other Indian languages spoken by minorities in Singapore include Malayalam, Telugu, Punjabi, Bengali, Hindi, and Gujarati.[2]

Eurasian languages

editKristang is a creole spoken by Portuguese Eurasians in Singapore and Malaysia. It developed when Portuguese colonisers incorporated borrowings from Malay, Chinese, Indian and Arab languages. When the British took over Singapore, Kristang declined as the Portuguese Eurasians learned English instead. Today, it is largely spoken by the elderly.[64]

Singapore Sign Language

editWhile Singapore Sign Language (SgSL) has not been recognised as a national sign language, the local deaf community recognises it as Singapore's native sign language, developed over six decades since the setting up of the first school for local deaf in 1954. Singapore Sign Language is closely related to American Sign Language and is influenced by Shanghainese Sign Language (SSL), Signing Exact English (SEE-II), Pidgin Signed English (PSE).

Other Malayo-Polynesian languages

editIn the 1824 census of Singapore, 18% of the population were identified as ethnic Bugis, speaking the Buginese language, counted separately from the Malays. Over the centuries, the Bugis community dwindled and became assimilated into the Malay demographic. In 1990, only 0.4% of Singaporeans were identified as Bugis. Today the term Malay is used in Singapore as an umbrella term for all peoples of the Malay Archipelago.

Bilingualism and multilingualism

editThe majority of Singaporeans are bilingual in English and one of the other three official languages. For instance, most Chinese Singaporeans can speak English and Mandarin. Some, especially the older generations, can speak Malay and additional Chinese varieties such as Hokkien, Teochew, Cantonese, Hakka, and Hainanese.

Bilingual education policy

editSingapore has a bilingual education policy, where all students in government schools are taught English as their first language. Students in Primary and Secondary schools also learn a second language called their "Mother Tongue" by the Ministry of Education, where they are either taught Mandarin, Malay, or Tamil.[65] English is the main language of instruction for most subjects,[2] while Mother Tongue is used in Mother Tongue lessons and moral education classes. This is because Singapore's "bilingualism" policy of teaching and learning English and Mother Tongue in primary and secondary schools is viewed as a "cultural ballast" to safeguard Asian cultural identities and values against Western influence.[66][67]

While "Mother Tongue" generally refers to the first language (L1) elsewhere, it is used to denote the "ethnic language" or the second language (L2) in Singapore. Prior to 1 January 2011, the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Singapore defined "Mother Tongue" not as the home language or the first language acquired by the student but by their father's ethnicity. For example, a child born to a Tamil-speaking Indian father and Hokkien-speaking Chinese mother would automatically be assigned to take Tamil as the Mother Tongue language.[68]

Since 1 January 2011, Mother Tongue is defined solely by a person's official registered race. If a person is of more than one ethnicity and their race is registered in the hyphenated format, the race chosen will be the one that precedes the hyphen in their registered race.[12]

The Lee Kuan Yew Fund for Bilingualism was set up on 28 November 2011. The Fund aims to promote bilingualism amongst young children in Singapore, is set up to supplement existing English and Mother Tongue language programmes in teaching and language learning. It is managed by a Board chaired by the Singapore's Minister of Education, Mr Heng Swee Keat and advised by an International Advisory Panel of Experts.[69]

Impacts of bilingual education policy

editThe impact of the bilingual policy differs amongst students from the various ethnic groups. For the Chinese, when the policy was first implemented, many students found themselves struggling with two foreign languages: English and Mandarin.[5] Even though several different Chinese varieties were widely spoken at home, they were excluded from the classroom as it was felt that they would be an "impediment to learning Chinese".[14] Today, although Mandarin is widely spoken, proficiency in second languages has declined.[5] In response to these falling standards, several revisions have been made to the education system. These include the introduction of the Mother Tongue "B" syllabus and the now-defunct EM3 stream, in both of which Mother Tongue is taught at a level lower than the mainstream standard. In the case of Mandarin, Chinese students would study Chinese "B".

The Malay-speaking community also faced similar problems after the implementation of the policy. In Singapore, Malay, not its non-standard dialects, is valued as a means of transmitting familial and religious values. For instance, "Madrasahs", or religious schools, mosques and religious classes all employ the Malay language.[70] However, Malay in turn is facing competition from the increased popularity of English.[2]

In contrast to the language policy for Mandarin and Malay, Indian students are given a wider variety of Indian languages to choose from. For example, Indian students speaking Dravidian languages study Tamil as a Mother Tongue.[2] However, schools with low numbers of Tamil students might not provide Tamil language classes. As a result, students from such schools will attend Tamil language classes at the Umar Pulavar Tamil Language Centre (UPTLC).[71] On the other hand, Indian students who speak non-Dravidian languages can choose from Hindi, Bengali, Punjabi, Gujarati and Urdu.[2] However, as with Tamil, only certain schools offer these non-Dravidian languages. Thus, students will attend their respective language classes at designated language centres, held by the Board for the Teaching and Testing of South Asian Languages (BTTSAL).[72]

In 2007, in a bid to enhance the linguistic experience of students, the Ministry of Education strongly encouraged schools to offer Conversational Malay and Chinese to those who do not take either of these languages as their Mother Tongue.[73] By providing the schools with the resources needed to implement the programme, the Ministry of Education has succeeded in significantly increasing the number of participating schools. More importantly, the programme was also well received by students.[74]

Challenges in the teaching of Mother Tongue

editThe teaching of Mother Tongue (especially Mandarin) in schools has encountered challenges due to more Singaporeans speaking and using English at home. The declining standards and command of Mandarin amongst younger generations of Chinese Singaporeans continue to be of concern to the older generations of Chinese Singaporeans, as they perceive it to be an erosion of Chinese culture and heritage.[5] This concern has led to the establishment of the Singapore Centre for Chinese Language (SCCL) by the government in November 2009.[75] The SCCL's stated purpose is to enhance the effectiveness of teaching Mandarin as a second language in a bilingual environment as well as to meet the learning needs of students from non-Mandarin speaking homes.[76]

Despite government efforts to promote Mandarin through the Speak Mandarin Campaign, the propagation of Mandarin and Chinese culture amongst Chinese Singaporeans continues to be a challenge because Mandarin faces stiff competition from the strong presence of English.[5] However, this situation is not only limited to Mandarin, but also Malay and Tamil, where rising statistics show that English is progressively taking over as the home language of Singaporeans.[2][10]

Foreign population in Singapore

editWith the influx of foreigners, the population of non-English speaking foreigners in Singapore offers new challenges to the concept of language proficiency in the country. Foreigners in Singapore constitute 36% of the population and they dominate 50% of Singapore's service sectors.[77] Thus, it is not uncommon to encounter service staff who are not fluent in English, especially those who do not use English regularly.[78] In response to this situation, the Straits Times reported that from July 2010, foreigners working in service sectors would have to pass an English test before they can obtain their work permits.[79]

Sociolinguistic issues

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2014) |

Politics

editLanguage plays an important role in Singapore's politics. Even until today, it is important for politicians in Singapore to be able to speak fluent English along with their Mother Tongue (including different varieties of Chinese) in order to reach out to the multilingual community in Singapore. This is evident in Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong's annual National Day Rally speech, which is communicated through the use of English, Malay and Mandarin.[80]

Before the 1980s, it was common for politicians to broadcast their speech in Malay, English, Singaporean Hokkien, Singaporean Mandarin and other Chinese varieties. For instance, during the 1960s, Lee Kuan Yew learned and used Hokkien frequently in his political or rally speeches, as it was vital for him to secure votes in elections from the Hokkien-speaking community. Similarly, Lim Chin Siong, who was charismatic in the use of Hokkien, was able to secure opposition votes. Facing competition and difficulty in securing votes from the Chinese-educated, Lee Kuan Yew also had to learn Mandarin, in order to win the votes from the Mandarin-speaking community.

Although the use of other Chinese varieties among the Singaporean population has dwindled,[10] they continue to be used in election rallies as of the 2011 parliamentary election. For instance, both Low Thia Khiang[81] and Chan Chun Sing[82] were noted for their usage of different Chinese varieties during election rallies.

Status of Singlish as an identity marker

editThere has been a continuous debate between the general Singaporean population and the Government with regard to the status of Singlish in local domains. While the government fears that the prevalence of Singlish would affect Singapore's overall image as a world class financial and business hub,[28] most Singaporeans on the other hand have chosen to embrace Singlish as an identity marker and as a language of solidarity.[83] In an attempt to eradicate the usage of Singlish, the government then began the Speak Good English Movement, encouraging people to use Standard Singaporean English in all contexts instead. Despite the success of the campaign, most Singaporeans surveyed still preferred the use of Singlish to communicate with fellow Singaporeans, and they also believed that they had the ability to code switch between Singlish and Standard Singaporean English, depending on the requirements of the particular situation.[83]

Most recently, Singlish came into the limelight when Republic of Singapore Air Force pilots supposedly used the language to much effect to prevent their American counterparts from intercepting their communications during the 2014 Red Flag exercise, resulting in a boost in support for the usefulness of Singlish among Singaporean netizens.[84]

Preservation issues

editChinese varieties (classified as dialects by the Singapore government), with the exception of Mandarin, have been in steep decline since the independence of Singapore in 1965. This is in part due to the Speak Mandarin Campaign that was launched in 1979. As part of the campaign, all programmes on TV and radio using non-standard varieties were stopped. Speeches in Hokkien by the prime minister were discontinued to prevent giving conflicting signals to the people.[85] By the late 1980s, Mandarin managed to some extent, to replace these varieties as the preferred language for communication in public places, such as restaurants and public transport.[86]

The preservation of local varieties in Singapore has been of increasing concern in Singapore since the 2000s, especially among the younger generation of Chinese youths.[87] This sudden revival of other varieties can mainly be attributed to a feeling of disconnection between the younger and the elder generations, as well as a sense of loss of identity from their own linguistic roots for many others.[88] While more work has to be put in to revive these varieties, the recent 2014 Singapore Teochew Festival[89] held in Ngee Ann City can be regarded as a positive sign that more people are becoming more actively involved in reconnecting with their linguistic roots.[90]

Controversy over learning of Chinese varieties

editIn March 2009, a newspaper article was published in Singapore broadsheet daily The Straits Times on a Language and Diversity Symposium organised by the Division of Linguistics and Multilingual Studies at Nanyang Technological University. Ng Bee Chin, acting Head of the Division, was quoted in the article as saying, "Although Singaporeans are still multilingual, 40 years ago, we were even more multilingual. Young children are not speaking some of these languages at all any more. All it takes is one generation for a language to die."[9]

The call to rethink the ban on dialects elicited a swift reply[91] from Minister Mentor, Lee Kuan Yew. "I thought it was a daft call. My then-principal private secretary Chee Hong Tat issued a reply[92] on my behalf: Using one language more frequently means less time for other languages. Hence, the more languages a person learns, the greater the difficulties of retaining them at a high level of fluency… It would be stupid for any Singapore agency or NTU to advocate the learning of dialects, which must be at the expense of English and Mandarin.’

A week later, Lee reiterated the point at the 30th anniversary launch of the Speak Mandarin Campaign. In his speech,[93] he described his personal experience with "language loss".

"To keep a language alive, you have to speak and read it frequently. The more you use one language, the less you use other languages. So the more languages you learn, the greater the difficulties of retaining them at a high level of fluency. I have learned and used six languages – English, Malay, Latin, Japanese, Mandarin and Hokkien. English is my master language. My Hokkien has gone rusty, my Mandarin has improved. I have lost my Japanese and Latin, and can no longer make fluent speeches in Malay without preparation. This is called "language loss."

Renewed interest in learning other Chinese varieties

editSince 2000, there has been a renewed interest in other Chinese varieties among Singaporean Chinese.[94] In 2002, clan associations such as Hainanese Association of Singapore (Kheng Chiu Hwee Kuan) and Teochew Poit Ip Huay Kuan started classes to teach other Chinese varieties.[95] This was in response to an increased desire among Singaporeans to reconnect with their Chinese heritage and culture through learning other Chinese varieties. In 2007, a group of 140 students from Paya Lebar Methodist Girls' Primary School learnt Hokkien-Taiwanese and Cantonese as an effort to communicate better with the elderly. The elderly themselves taught the students the varieties. The programme was organised in the hope of bridging the generational gap that was formed due to the suppression of these dialects in Singapore.[96]

Likewise, third-year students from Dunman High can now take a module called "Pop Song Culture". This module lets them learn about pop culture in different dialect groups through pop songs from the 70s and 80s performed in different varieties. Besides this, students can also take an elective on different flavours and food cultures from various dialect groups.[97]

Although the Singapore government appears to have relaxed its stance towards Chinese varieties in recent years, the fact is that they still did not actively support the widespread use of other Chinese varieties especially in the Singapore mainstream Television media. Recently, the Singapore Government allowed some local produced mini "chinese dialect" shows to be broadcast in Hokkien-Taiwanese and Cantonese dedicated to the Singapore Chinese elderly who speak Hokkien-Taiwanese or Cantonese but did not understand English or Mandarin Chinese. The aim of the local produced mini "chinese dialect" shows is to transmit important messages about social services and medical services and care to the Singapore Chinese Elderly. However, there are limited number of "Chinese Dialect" shows that could be broadcast on Singapore's Mainstream Television due to the Singapore's Government stringent language policy.

Linguistic landscape of Singapore

editThe multi-ethnic background of Singapore's society can be seen in its linguistic landscape. While English dominates as the working language of Singapore, the city does not possess a monolingual linguistic landscape. This can be seen from the variety of signs strewn around the city. Signs are colour-coded and categorised by their respective functions: for example, signs pointing to attractions are brown with white words, while road signs and street names are green with white words. Some of the most evident signs of multilingualism in Singapore's linguistic landscape include danger/warning signs at construction sites, as well as road signs for tourist attractions. By observing the variation in languages used in the different contexts, it is possible to obtain information on the ethnolinguistic vitality of the country.

Tourist attractions

editThe majority of Singapore's tourist attractions provide information through English in the Roman script. In many cases, the entrances of the attraction is written in English (usually with no other accompanying languages) while the distinctive brown road signs seen along streets and expressways which direct tourists come in up to four or five languages, with English as the largest and most prominent language on the sign.

Some examples of the different ways in which popular tourist attractions in Singapore display ethnolinguistic diversity can be seen at tourist attractions such as Lau Pa Sat, where the words "Lau Pa Sat" on the directory boards consist of the Mandarin Chinese word lau for "old" (老;lǎo) and from the Hokkien words pa sat for "market" (巴刹;bā sha), written in roman script. The entrance sign of the attraction also includes a non-literal translation in English below its traditional name (Festival Market). It is also called the Telok Ayer Market, a name which makes reference to the location of the attraction and does not have anything to do with its cultural name.

The conversion and expression in Roman script of Mandarin and Hokkien into pīnyīn helps non-Mandarin and non-Hokkien speakers with the pronunciation of the name of a place whilst remaining in tandem with the use of English and Roman script in Singapore. The repackaging of the original names of Lau Pa Sat in Roman script, and inclusion of the appearance of an English translation as a secondary title can be seen as a way of heightening the sense of authenticity and heritage of the attraction as it is marketed as a culturally-rich area in Singapore, similar to Chinatown and Little India; both of which were formerly cultural enclaves of the distinctive races. Similarly in places that bear cultural significance, the signs are printed in the language associated with the culture, such as The Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall which has an entirely Chinese sign without any translations.

Some notable exceptions include the brown directional road signs for the Merlion Park which are written not only in the four national languages, but also in Japanese. Although many variations exist, this arrangement is widely applied to most places of interest as well as places of worship, such as the Burmese Buddhist Temple which has signs in Burmese and some mosques in Singapore which also have their names printed in the Jawi script even though the Malay language was standardised with the Roman alphabet in Singapore.

Government offices and public buildings

editThis section possibly contains original research. (February 2022) |

Despite the fact that Malay is the national language of Singapore, government buildings are often indicated by signs in English and not Malay. Comparing the relative occurrences of English and Malay in building signs, the use of the working language is far more common in Singapore's linguistic landscape than that of the national language, which is limited to ceremonial purposes. This can also be seen on the entrance sign to most Ministries and government buildings, which are expressed only in English, the working language.

Most of the foreign embassies in Singapore are able to use their own national or working languages as a representation of their respective embassies in Singapore, as long as their language can be expressed in the script of any of Singapore's official languages. For example, embassies representing non-English speaking countries such as the French Embassy are allowed to use their own languages because the language can be expressed in Roman script, thus explaining why the French embassy uses its French name. However, for the case of the Royal Thai Embassy, English was chosen to represent it in Singapore because the Thai script is not recognised as a script in any of Singapore's official languages, even though English is less widely used in Thailand than standard Thai.

Public hospitals

editOut of the eight general hospitals overseen by Singapore's Ministry of Health, only Singapore General Hospital has signages in the four official languages. Along Hospital Drive (where Singapore General Hospital is located) and various national medical centres, road directories are entirely in English. Within the hospital itself, signs for individual blocks, wards, Accident and Emergency department, Specialist Outpatient Clinics, National Heart Centre and National Cancer Centre have signs written in the four official languages. The English titles are still expressed with the largest font first, followed by Malay, Chinese and Tamil in smaller but equally-sized fonts, which is in accordance with order given by Singapore's constitution. Surprisingly, the Health Promotion Board, National Eye and Dental Centres, which are also in the same region, have English signs only. All of the other seven public hospitals have their "Accident and Emergency" sign in English only, with some highlighted in a red background.

Notices and campaigns

editMessages and campaigns that have a very specific target audience and purpose are usually printed in the language of intended readers. For example, the "No Alcohol" signs put up along Little India after the Little India Riots are notably printed in only Tamil and English as a reflection of the racial demographics in the region.

During the 2003 SARS epidemic, the government relied heavily on the media to emphasise the importance of personal hygiene, and also to educate the general public on the symptoms of SARS, in which a Singlish rap video featuring Gurmit Singh as Phua Chu Kang was used as the main medium. Similarly in 2014, the Pioneer Generation Package[98] (for senior citizens above 65 years of age in 2014 who obtained Singapore citizenship on or before 31 December 1986) made use of Chinese varieties commonly spoken in Singapore such as Hokkien, Cantonese and Teochew, and also Singlish in order to make the policies more relatable,[99] and at the same time raise awareness about the benefits that this new scheme provides for them. These allowances of different language varieties is an exception to the four official languages. This exception is seen for campaigns that are deemed as highly important, and include the elderly, or those who are not as proficient in the English language as the target audience.

Limitations in current research methodologies

editWhile the above examples show how the different languages are used on signs within Singapore, there is scant data on the motivations behind these variations seen, as exemplified by the advisory for "No Alcohol" sales in Little India, which showcased a rare variation from the usage of the four main languages that are commonly seen on most advisory signs. Similarly, the Ministry of Health, in a response to a feedback requesting all hospitals to have four languages on its entrances, has claimed that usage of pictorial signages was better in conveying messages, as opposed to using all four languages.[100] Due to problems in the research methodology[101] and lack of governmental statutes that explain these variations, the study on the linguistics landscape in Singapore remain as a controversial field. These problems include non-linearity, where the large numbers of variations seen in Singapore prevents the application of any trends to understand the landscape; and also the lack of any standard legislation that determines any fixed rules on usage of languages on signs.

Controversies

editIn a 2012 pilot program, SMRT trains began announcements of station names in both English and Mandarin Chinese so as to help Mandarin Chinese-speaking senior citizens cope better with the sudden increase in new stations.[102] However, this received mixed reactions from the public. Some people pointed out that there were senior citizens who did not speak Mandarin, while others complained of feeling alienated. In reaction to this, SMRT claimed that the announcements were only recorded in English and Mandarin because the Malay and Tamil names of stations sounded very similar to the English names.[citation needed]

In 2013, a group of Tamil speakers petitioned the Civil Aviation Authority of Singapore to include Tamil instead of Japanese on all the signs in the Singapore Changi Airport. Even though only 5% of Singapore's population speaks Tamil, they argued that since Tamil is one of the four official languages of Singapore, it should be used to reflect Singapore's multi-racial background.[citation needed]

In 2014, there were reports of erroneous translations on road signs of popular tourist attractions such as Lau Pa Sat and Gardens by the Bay made by the Singapore Tourism Board.[103]

Media and the arts

editThe free-to-air channels in Singapore are run by Mediacorp and each channel is aired in one of the four official languages of Singapore. For example, Channel U and Channel 8 are Mandarin-medium channels, Channel 5 and CNA are English-medium channels, Suria is a Malay-medium channel, and Vasantham is a predominantly Tamil-medium channel. However, these channels might also feature programmes in other languages. For example, apart from programmes in Mandarin, Channel U also broadcasts Korean television programmes at specific allotted times.

Chinese varieties in local films

editThe use of Chinese varieties other than Mandarin in Singapore media is restricted by the Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts (MICA). The rationale given for the resistance towards nonstandard Chinese varieties was that their presence would hinder language learning of English and Mandarin.[104] However, in order to cater to older Singaporeans who speak only non-standard Chinese varieties, videos, VCDs, DVDs, paid subscription radio services and paid TV channels are exempted from MICA's restrictions. Two free-to-air channels, Okto and Channel 8, are also allowed to show operas and arthouse movies with some non-standard variety content, respectively.[105]

The use of Chinese varieties is not controlled tightly in traditional arts, such as Chinese opera. As such, they have managed to survive, and even flourish in these areas. In Singapore, various types of Chinese opera include Hokkien, Teochew, Hainanese and Cantonese. In the past, this diversity encouraged the translation between varieties for scripts of popular stories. After the implementation of the bilingual policy and Speak Mandarin Campaign, Mandarin subtitles were introduced to help the audience understand the performances. Today, as usage of English rises, some opera troupes not only provide English subtitles but also English translations of their works. For these English-Chinese operas, subtitles may be provided in either Mandarin, other Chinese varieties, or both. In this way, Chinese opera will be able to reach out to a wider audience despite being variety-specific.[106]

Similar to Chinese opera, there are no language restrictions on entries for film festivals. In recent years, more local film makers have incorporated non-standard Chinese varieties into their films.[106] For example, the local movie 881 revived the popularity of getai after it was released. Getai, which is mainly conducted in Hokkien and Teochew, became more popular with the younger generations since the release of the movie. On the effect triggered by the release of the movie 881, Professor Chua Beng Huat, Head of the Department of Sociology of the National University of Singapore, commented in the Straits Times that "putting Hokkien on the silver screen gives Hokkien a kind of rebellious effect. It's like the return of the repressed."[107] The success of 881 is also reflected by album sales of 881 movie soundtrack, which became the first local film soundtrack to hit platinum in Singapore.[108] In other instances, the movie Singapore Ga Ga, a tissue seller sings a Hokkien song while Perth features a Singaporean taxi driver using Hokkien and Cantonese. Local directors have commented that non-standard Chinese varieties are vital as there are some expressions which just cannot be put across in Mandarin Chinese, and that the different Chinese varieties are an important part of Singapore that adds a sense of authenticity that locals will enjoy.[106]

Indian languages in the media

editIndian languages besides Tamil are managed slightly differently from the Chinese varieties. Even though only Tamil has official language status, there have been no attempts to discourage the use of other Indian languages such as Bengali, Gujarati, Hindi, Malayalam, Punjabi, Telugu, and Urdu. For one, movies in these languages are shown in some local cinemas, such as Rex and Screens of Bombay Talkies.[109] Furthermore, the local Indian TV channel Vasantham has also allocated specific programme timeslots to cater to the variety of Indian language speakers in Singapore.

Language-specific societies

editChinese clan associations play a role in maintaining the non-standard Chinese varieties. In the past, they provided support to migrant Chinese, based on the province they originated. Today, they provide a place for people who speak the same variety to gather and interact. For example, the Hokkien Huay Kuan holds classes for performing arts, calligraphy, and Hokkien Chinese. They also organise the biennial Hokkien Festival, which aims to promote Hokkien customs and culture.[110] With such efforts, perhaps non-standard Chinese varieties in Singapore will be better equipped to resist erosion.[111]

Apart from the efforts to maintain local Chinese varieties, the Eurasian Association holds Kristang classes for people who are interested in learning Kristang. In this way, it hopes to preserve what it perceives to be a unique part of the Eurasian heritage in Singapore.[64]

Notes

edit- ^ "The national language shall be the Malay language and shall be in the Roman script …" (Constitution of the Republic of Singapore, PART XIII).

References

edit- ^ "Singapore Infopedia".

- ^ a b c d e f g h Dixon, L.Q. (2009). "Assumptions behind Singapore's language-in-education policy: Implications for language planning and second language acquisition". Language Policy. 8 (2): 117–137. doi:10.1007/s10993-009-9124-0. S2CID 143659314.

- ^ David, Maya Esther (2008). "Language Policies Impact on Language Maintenance and Teaching Focus on Malaysia Singapore and The Philippines" (PDF). University of Malaya Angel David Malaysia. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- ^ Lewis, M. Paul (2009). "Languages of Singapore". Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Archived from the original on 25 May 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lee, C.L. (2013). "Saving Chinese-language education in Singapore". Current Issues in Language Planning. 13 (4): 285–304. doi:10.1080/14664208.2012.754327. S2CID 143543454.

- ^ a b c Bao, Z.; Aye, K.K. (2010). "Bazaar Malay topics". Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages. 25 (1): 155–171. doi:10.1075/jpcl.25.1.06bao.

- ^ "Address By President Halimah Yacob For Second Session Of The Thirteenth Parliament". 2018.

- ^ Goh, Chok Tong (11 October 2014). "English version of Speech in Mandarin by the Prime Minister, Mr Goh Chok Tong". Speak Mandarin Campaign. Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

- ^ a b Abu Baker, Jalelah (8 March 2009). "One generation – that's all it takes 'for a language to die'". The Straits Times. Singapore. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Census of Population 2010 Archived 13 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine" (table 4), Singapore Department of Statistics. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ See Language education in Singapore.

- ^ a b "Greater Flexibility with Implementation of Double-Barrelled Race Option from 1 January 2011". Archived from the original on 26 November 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ^ Gupta, A.F. Fischer, K. (ed.). "Epistemic modalities and the discourse particles of Singapore". Approaches to Discourse Particles. Amsterdam: Elsevier: 244–263. Archived from the original (DOC) on 5 February 2011. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ a b Dixon, L. Quentin. (2005). The Bilingual Education Policy in Singapore: Implications for Second Language Acquisition. In James Cohen, J., McAlister, K. T., Rolstad, K., and MacSwan, J (Eds.), ISB4: Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Bilingualism. p. 625-635, Cascadilla Press, Somerville, MA.

- ^ "31 March 2000". Moe.gov.sg. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- ^ What are some commonly misspelled English words?|ASK!ASK! Archived 3 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tan, Sherman, p. 340-341. "The four recognised official languages are English, Mandarin, Tamil, and Malay, but in practice, English is Singapore's default lingua franca."

- ^ Pakir, Anne (1999). "Bilingual education with English as an official language: Sociocultural implications" (PDF). Georgetown University Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2013. ()

- ^ "Bilingual Education". National Library Board, Singapore. 12 November 2009. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ Deterding, David. (2007). Singapore English. Edinburgh University Press.

- ^ Singapore English definition – Dictionary – MSN Encarta. Archived from the original on 30 July 2003.

- ^ "Singapore Company Registration and Formation". Healy Consultants. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- ^ Tan, Amelia (29 December 2009). "Refine bilingual policy". The Straits Times. Singapore. Archived from the original on 31 December 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ Census of Population 2010 Statistical Release 1: Demographic Characteristics, Education, Language and Religion (PDF). Department of Statistics, Ministry of Trade & Industry, Republic of Singapore. January 2011. ISBN 978-981-08-7808-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2011. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- ^ General Household Survey 2015 Archived 20 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine p. 18

- ^ "Demographics, Characteristics, Education, Language and Religion" (PDF). Statistics Singapore. 2020.

- ^ "Chinese-based lexicon in Singapore English, and Singapore-Chinese culture" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 November 2010. Retrieved 18 April 2010.

- ^ a b Tan, Hwee Hwee (29 July 2002). "A war of words over 'Singlish'". Time Magazine. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- ^ "Use of Language Article 21. a." (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 February 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ "Singlish and our National Identity". www.sg101.gov.sg. Retrieved 13 May 2023.

- ^ Mathews, Mathews; Tay, Melvin; Selvarajan, Shanthini; Tan, Zhi Han. "Language Proficiency, Identity & Management: Results From the IPS Survey on Race, Religion, & Language" (PDF). lkyspp.nus.edu.sg. Retrieved 13 May 2023.

- ^ Auto, Hermes (15 June 2020). "Singaporeans feel English should be main language used in public, with space for other languages: IPS study | The Straits Times". www.straitstimes.com. Retrieved 13 May 2023.

- ^ "The language the government tried to suppress". BBC Culture. 19 September 2016. Archived from the original on 10 July 2019. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ a b c "Census 2020" (PDF). Singapore Department of Statistics. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 June 2022. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- ^ a b Lee, Edmund E. F. "Profile of the Singapore Chinese Dialects" (PDF). Singapore Department of Statistics, Social Statistics Section. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- ^ Lee Kuan Yew, From Third World to First: The Singapore Story: 1965–2000, HarperCollins, 2000. ISBN 0-06-019776-5.

- ^ "Mandarin will become Singaporean mother tongue – People's Daily Online". People's Daily. Archived from the original on 15 October 2012. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- ^ "Dominant Home Language of Chinese Primary One Students". Ministry of Education, Singapore. Archived from the original on 26 December 2010. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- ^ a b Tan, Sherman, p. 341.

- ^ Oi, Mariko (5 October 2010). "BBC News – Singapore's booming appetite to study Mandarin". BBC. Archived from the original on 28 September 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- ^ "Singapore – Language". Countrystudies.us. Archived from the original on 21 November 2010. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- ^ "Chapter 2 Education and Language" (PDF). General Household Survey 2005, Statistical Release 1: Socio-Demographic and Economic Characteristics. Singapore Department of Statistics. 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ Fagao Zhou (1986). Papers in Chinese Linguistics and Epigraphy. Chinese University Press. p. 56. ISBN 9789622013179. Archived from the original on 20 July 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- ^ Constitution, Article 153A.

- ^ Tan, P.K.W. (2014). "Singapore's balancing act, from the perspective of the linguistic landscape". Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia. 29 (2): 438–466. doi:10.1355/sj29-2g. S2CID 143547411. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ Singapore Arms and Flag and National Anthem Act (Cap. 296, 1985 Rev. Ed.)

- ^ Hamilton, A. W. (1922). "Penang Malay". Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 85 (1–2): 67–96. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00105970. JSTOR 41561397.

- ^ Benjamin, Geoffrey (2021). "Singapore's 'other' Austronesian languages: What do we know?". In Jain, Ritu (ed.). Multilingual Singapore: language policies and linguistic realities. London, New York: Routledge. pp. 116–7. ISBN 9780429280146.

- ^ a b Phyllis Ghim-Lian Chew (2012). A Sociolinguistic History of Early Identities in Singapore: From Colonialism to Nationalism (illustrated ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 78–84. ISBN 9781137012333. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ^ a b Fishman, Joshua A (1993). The Earliest Stage of Language Planning: "The First Congress" Phenomeno (illustrated ed.). Walter de Gruyter. pp. 184–185. ISBN 9783110848984. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ^ Cook, Vivian; Bassetti, Benedetta (2005). Second Language Writing Systems. Multilingual Matters. p. 359. ISBN 9781853597930. Archived from the original on 19 July 2019. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ^ "Update Change of Name in IC". Immigration and Checkpoints Authority. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ^ Clyne, Michael G (1992). Pluricentric Languages: Differing Norms in Different Nations. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 410–411. ISBN 9783110128550. Archived from the original on 22 November 2016. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ^ Mohd Aidil Subhan bin Mohd Sulor (2013). "Standardization or Uniformity: in Pursuit of a Guide for Spoken Singapore Malay" (PDF). E-Utama. 4.

- ^ Mikhlis Abu Bakar; Lionel Wee (2021). "Pronouncing the Malay identity". In Jain, Ritu (ed.). Multilingual Singapore: Language Policies and Linguistic Realities. Routledge. ISBN 9781000386929.

- ^ Euvin Loong Jin Chong; Mark F. Seilhamer (18 August 2014). "Young people, Malay and English in multilingual Singapore". World Englishes. 33 (3): 363–365. doi:10.1111/weng.12095.

- ^ Gloria R. Poedjosoedarmo (1997). "What is Happening to Malay in Singapore?". In Odé, Cecilia (ed.). Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics: Leiden 22–27 August 1994. Rodopi. ISBN 9789042002531.

- ^ Gupta, Anthea Fraser, Singapore Colloquial English (Singlish) Archived 18 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Language Varieties. Retrieved 2013-11-11.

- ^ Reinhard F Hahn, "Bahasa Baba Archived 2 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine". Retrieved 2010-11-18.

- ^ "Census of Population 2010: Advance Census Release" (PDF). Singapore Department of Statistics. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2012. Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- ^ Schiffman, Harold F. (1995). "Language Shift in the Tamil Communities of Malaysia and Singapore: the Paradox of Egalitarian Language Policy". Language Loss and Public Policy. 14 (1–2). Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ^ Schiffman, Harold (2007). "Tamil Language Policy in Singapore". In Vaish, Viniti; Gopinathan, Saravanan; Liu, Yongbing (eds.). Language, capital, culture : critical studies of language and education in Singapore. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. pp. 226–228. ISBN 978-9087901233. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- ^ tamilarasan (29 May 2024). "Tamil Boy Baby Names starting with அ (A) - தமிழ் உலகம் ✨". Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ a b de Rozario, Charlotte (2006). "Kristang: a language, a people" (PDF). Community Development Council. Singapore. Retrieved 18 November 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Language and Globalization: Center for Global Studies at the University of Illinois". Archived from the original on 10 May 2013.

- ^ Chan, Leong Koon (2009). "Envisioning Chinese Identity and Managing Multiracialism in Singapore" (PDF). University of New South Wales, Nanyang Technological University of Singapore. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- ^ Vaish, V (2008). "Mother tongues, English, and religion in Singapore". World Englishes. 27 (3/4): 450–464. doi:10.1111/j.1467-971x.2008.00579.x.

- ^ Romaine, Suzanne. (2004). The bilingual and multilingual community. In Bhatia, Tej K. and Ritchie, William C. (eds). The Handbook of Bilingualism. pp. 385–406. Oxford: Blackwell.

- ^ "About the Fund". Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ Kassim, Aishah Md (2008). "Malay Language As A Foreign Language And The Singapore's Education System. In". GEMA Online Journal of Language Studies. 8 (1): 47–56.

- ^ "Our function as UPTLC". Umar Pulavar Tamil Language Centre, Ministry of Education, Singapore. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- ^ The Board (2014). Board for the Teaching & Testing of South Asian Languages(BTTSAL). Retrieved 18 October 2014, from "Bttsal – Bttsal". Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ^ Ministry of Education Media Centre (2007). "Nurturing language proficiency amongst singaporeans". Archived from the original on 28 October 2010. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

- ^ Tan, Amelia (22 July 2008). "Conversational Chinese and Malay at more schools". Asiaone. Singapore. Archived from the original on 22 May 2009. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

- ^ Oon, Clarissa (8 September 2008). "PM: Don't lose bilingual edge". Asiaone. Singapore. Archived from the original on 28 January 2012. Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- ^ "SCCL". Archived from the original on 15 March 2012. Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- ^ "Population Trends 2009" (PDF). Department of Statistics, Ministry of Trade & Industry, Republic of Singapore. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 13 October 2010.

- ^ Jamie Ee, Wen Wei, "Sorry, no English Archived 5 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine", AsiaOne, 1 September 2009.

- ^ "English test for foreign service staff from July". 26 January 2010. Archived from the original on 31 January 2010. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- ^ "Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong's National Day Rally 2014(Speech in Malay)". Government of Singapore. Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- ^ Phua, A. (9 February 2012). "Teochew candidate key to their votes". The New Paper. Archived from the original on 27 October 2014. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- ^ Tan, L (11 May 2012). "Life after GE – Chan Chun Sing". The New Paper. Archived from the original on 27 October 2014. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- ^ a b "The Roles of Singapore Standard English and Singlish" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- ^ Loo, G (23 May 2014). "Come in Kangkong Commander! Mr Brown gives his take on air force Singlish". The New Paper. Archived from the original on 10 July 2015. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- ^ "Use of dialects interfere with learning of Mandarin & English". Singapore: Channel NewsAsia. 6 March 2009. Archived from the original on 7 March 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ Liang, Chong Ching (1999). "Inter-generational cultural transmission in Singapore: A brief discussion". Oral History Centre, National Archives of Singapore. Archived from the original on 24 January 2016. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- ^ Lai, L (23 October 2013). "Young people speak up for dialects". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on 19 October 2014. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- ^ Ng, J.Y.; Woo, S.B. (22 April 2012). "Dialects find a voice" (PDF). The Straits Times. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- ^ "ABOUT TEOCHEW FESTIVAL 2014". Archived from the original on 28 October 2014. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- ^ Mendoza, D. (25 September 2014). "Singapore Teochew Festival: Celebrating tradition with modern approaches". Today Online. Archived from the original on 16 October 2014. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- ^ Lee, Kuan Yew (2012). My Lifelong Challenge: Singapore's Bilingual Journey. Straits Times Press. pp. 166–167.

- ^ Foolish to Advocate The Learning of Dialects, Straits Times Forum letter, 7 March 2009

- ^ "SPEECH BY MR LEE KUAN YEW, MINISTER MENTOR, AT SPEAK MANDARIN CAMPAIGN'S 30TH ANNIVERSARY LAUNCH, 17 MARCH 2009, 5:00 PM AT THE NTUC AUDITORIUM". National Archives of Singapore.

- ^ Phyllis Ghim-Lian Chew (2009). "An Ethnographic Survey of Language Use, Attitudes and Beliefs of Singaporean Daoist Youths" (PDF). Asian Research Institute, Nanyang Technological University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 September 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2010. ()

- ^ "Dialects draw more new learners". The Straits Times. 9 April 2009. Archived from the original on 4 September 2009. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- ^ Yeo, Jessica (6 May 2007). "Students learn dialect to communicate with elderly". ChannelNewAsia. Singapore. Archived from the original on 24 April 2011. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ Yanqin, Lin (21 April 2008). "Dialects spark new bonding". Singapore: Channel NewsAsia. Archived from the original on 19 February 2014. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)". www.pioneers.gov.sg. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ "Raising Awareness of the Pioneer Generation Package". Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ "Hospital Signages | Ministry of Health". www.moh.gov.sg. Archived from the original on 19 October 2014. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ^ Tufi, Stefania; Blackwood, Robert (2010). "Trademarks in the linguistic landscape: methodological and theoretical challenges in qualifying brand names in the public space". International Journal of Multilingualism. 7 (3): 197–210. doi:10.1080/14790710903568417. S2CID 145448875.

- ^ "Guide to Singapore: Movies, Events and Restaurant Deals". Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ Abu Baker, Jalelah (6 November 2014). "Wrong Tamil translation of Lau Pa Sat name makes its rounds on Facebook". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on 21 May 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ Ng, C.L.P. (2014). "Mother tongue education in Singapore: Concerns, issues and controversies". Current Issues in Language Planning. 15 (4): 361–375. doi:10.1080/14664208.2014.927093. S2CID 143265937.

- ^ "Provision of More Dialect Programmes". REACH Singapore. Singapore. 26 March 2009. Archived from the original on 5 January 2011. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- ^ a b c Foo, Lynlee (6 July 2008). "Local filmmakers include more Chinese dialects in recent works" (reprint). Singapore: Channel NewsAsia. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ^ "Singapore film on music for dead brings Hokkien to life". Reuters. 1 September 2007. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- ^ "Eric Ng on 881 Soundtrack 2". Sinema.Sg. 20 October 2007. Archived from the original on 8 May 2011. Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- ^ See List of cinemas in Singapore.

- ^ "All things Hokkien in Fest". The Straits Times. Singapore. 15 October 2008. Archived from the original on 9 October 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- ^ Chua, Soon Pong (2007). "Translation and Chinese Opera: The Singapore Experience". Singapore: Chinese Opera Institute. Archived from the original (doc) on 12 September 2011. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

Further reading

edit- Bokhorst-Heng, Wendy D.; Santos Caleona, Imelda (2009). "The language attitudes of bilingual youth in multilingual Singapore". Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. 30 (3): 235–251. doi:10.1080/01434630802510121. S2CID 145000429.

- Tan, Sherman (2012). "Language ideology in discourses of resistance to dominant hierarchies of linguistic worth: Mandarin Chinese and Chinese 'dialects' in Singapore". The Australian Journal of Anthropology. 23 (3): 340–356. doi:10.1111/taja.12004.