A major contributor to this article appears to have a close connection with its subject. (December 2021) |

Lakota (Lakȟótiyapi [laˈkˣɔtɪjapɪ]), also referred to as Lakhota, Teton or Teton Sioux, is a Siouan language spoken by the Lakota people of the Sioux tribes. Lakota is mutually intelligible with the two dialects of the Dakota language, especially Western Dakota, and is one of the three major varieties of the Sioux language.

| Lakota | |

|---|---|

| Lakȟótiyapi | |

| Pronunciation | [laˈkˣɔtɪjapɪ] |

| Native to | United States, with some speakers in Canada |

| Region | Primarily North Dakota and South Dakota, but also northern Nebraska, southern Minnesota, and northern Montana |

| Ethnicity | Teton Sioux |

Native speakers | (2,100, 29% of ethnic population cited 1997–2016)[1] |

Siouan

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | lkt |

| Glottolog | lako1247 |

| ELP | Lakota |

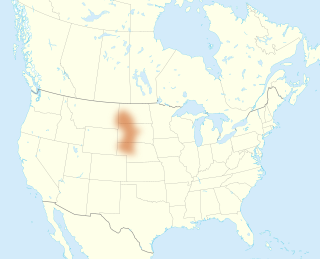

Core pre-contact Lakota territory | |

| Lakota "ally / friend" | |

|---|---|

| People | Lakȟóta Oyáte |

| Language | Lakȟótiyapi |

| Country | Lakȟóta Makóce, Očhéthi Šakówiŋ |

Speakers of the Lakota language make up one of the largest Native American language speech communities in the United States, with approximately 2,000 speakers, who live mostly in the northern plains states of North Dakota and South Dakota.[1] Many communities have immersion programs for both children and adults.

Like many indigenous languages, the Lakota language did not have a written form traditionally. However, efforts to develop a written form of Lakota began, primarily through the work of Christian missionaries and linguists, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The orthography has since evolved to reflect contemporary needs and usage.

One significant figure in the development of a written form of Lakota was Ella Cara Deloria, also called Aŋpétu Wašté Wiŋ (Beautiful Day Woman), a Yankton Dakota ethnologist, linguist, and novelist who worked extensively with the Dakota and Lakota peoples, documenting their languages and cultures. She collaborated with linguists such as Franz Boas and Edward Sapir to create written materials for Lakota, including dictionaries and grammars.[2]

Another key figure was Albert White Hat Sr., who taught at and later became the chair of the Lakota language program at his alma mater, Sinte Gleska University at Mission, South Dakota, one of the first tribal-based universities in the US.[3] His work focused on the Sicangu dialect using an orthography developed by Lakota in 1982 and which today is slowly supplanting older systems provided by linguists and missionaries.

History and origin

editThe Lakota people's creation stories say that language originated from the creation of the tribe.[4][5] Other creation stories say language was invented by Iktomi.[6]

A wholly Lakota newspaper named the Anpao Kin ("Daybreak") circulated from 1878 by the Protestant Episcopal Church in Niobrara Mission, Nebraska until its move to Mission, South Dakota in 1908 continuing until its closure in 1937. The print alongside its Dakota counterpart Iapi Oaye ("The Word Carrier") played an important role in documenting the enlistment and affairs including obituaries of Native Sioux soldiers into the army as America became involved in World War I.[7]

Phonology

editVowels

editLakota has five oral vowels, /i e a o u/, and three nasal vowels, /ĩ ã ũ/ (phonetically [ɪ̃ ə̃ ʊ̃]). Lakota /e/ and /o/ are said to be more open than the corresponding cardinal vowels, perhaps closer to [ɛ] and [ɔ]. Orthographically, the nasal vowels are written with a following ⟨ƞ⟩, ⟨ŋ⟩, or ⟨n⟩; historically, these were written with ogoneks underneath, ⟨į ą ų⟩.[8] No syllables end with consonantal /n/.

| Front | Central | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Close/High | oral | i ⟨i⟩ | u ⟨u⟩ | |

| nasal | ĩ ⟨iŋ⟩ | ũ ⟨uŋ⟩ | ||

| Mid | e ⟨e⟩ | o ⟨o⟩ | ||

| Open/Low | oral | a ⟨a⟩ | ||

| nasal | ã ⟨aŋ⟩ | |||

A neutral vowel (schwa) is automatically inserted between certain consonants, e.g. into the pairs ⟨gl⟩, ⟨bl⟩ and ⟨gm⟩. So the clan name written phonemically as ⟨Oglala⟩ has become the place name Ogallala.

Consonants

edit| Bilabial | Dental | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Velar | Uvular[9][10] | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasals | m ⟨m⟩ | n ⟨n⟩ | ŋ ⟨ň⟩ | |||||

| Plosives and affricates |

voiceless | p ⟨p⟩ | t ⟨t⟩ | tʃ ⟨č⟩ | k ⟨k⟩ | ʔ ⟨ʼ⟩ | ||

| voiced | b ⟨b⟩ | ɡ ⟨g⟩ | ||||||

| aspirated | pʰ ⟨ph⟩ / pˣ ⟨pȟ⟩ |

tʰ ⟨th⟩ / tˣ ⟨tȟ⟩ |

tʃʰ ⟨čh⟩ | kʰ ⟨kh⟩ / kˣ ⟨kȟ⟩ |

||||

| ejective | pʼ ⟨pʼ⟩ | tʼ ⟨tʼ⟩ | tʃʼ ⟨čʼ⟩ | kʼ ⟨kʼ⟩ | ||||

| Fricative | voiceless | s ⟨s⟩ | ʃ ⟨š⟩ | χ ⟨ȟ⟩ | h ⟨h⟩ | |||

| voiced | z ⟨z⟩ | ʒ ⟨ž⟩ | ʁ ⟨ǧ⟩ | |||||

| ejective | sʼ ⟨sʼ⟩ | ʃʼ ⟨šʼ⟩ | χʼ ⟨ȟʼ⟩ | |||||

| Approximant | w ⟨w⟩ | l ⟨l⟩ | j ⟨y⟩ | |||||

The voiced uvular fricative /ʁ/ becomes a uvular trill ([ʀ]) before /i/[9][10] and in fast speech it is often realized as a voiced velar fricative [ɣ]. The voiceless aspirated plosives have two allophonic variants each: those with a delay in voicing ([pʰ tʰ kʰ]), and those with velar friction ([pˣ tˣ kˣ]), which occur before /a/, /ã/, /o/, /ĩ/, and /ũ/ (thus, lakhóta, /laˈkʰota/ is phonetically [laˈkˣota]). For some speakers, there is a phonemic distinction between the two, and both occur before /e/. No such variation occurs for the affricate /tʃʰ/. Some orthographies mark this distinction; others do not. The uvular fricatives /χ/ and /ʁ/ are commonly spelled ⟨ȟ⟩ and ⟨ǧ⟩.

All monomorphemic words have one vowel which carries primary stress and has a higher tone than all other vowels in the word. This is generally the vowel of the second syllable of the word, but often the first syllable can be stressed, and occasionally other syllables as well. Stress is generally indicated with an acute accent: ⟨á⟩, etc. Compound words will have stressed vowels in each component; proper spelling will write compounds with a hyphen. Thus máza-ská, literally "metal-white", i.e. "silver; money" has two stressed vowels, the first a in each component. If it were written without the hyphen, as mazaska, it would imply a single main stress.

Phonological processes

editA common phonological process which occurs in rapid speech is vowel contraction, which generally results from the loss of an intervocalic glide. Vowel contraction results in phonetic long vowels (phonemically a sequence of two identical vowels), with falling pitch if the first underlying vowel is stressed, and rising pitch if the second underlying vowel is stressed: kê: (falling tone), "he said that", from kéye; hǎ:pi (rising tone), "clothing", from hayápi. If one of the vowels is nasalized, the resulting long vowel is also nasalized: čhaŋ̌:pi, "sugar", from čhaŋháŋpi.[9]

When two vowels of unequal height contract, or when feature contrasts exist between the vowels and the glide, two new phonetic vowels, [æː] and [ɔː], result:[9] iyæ̂:, "he left for there", from iyáye; mitȟa:, "it's mine", from mitȟáwa.

The plural enclitic =pi is frequently changed in rapid speech when preceding the enclitics =kte, =kiŋ, =kštó, or =na. If the vowel preceding =pi is high/open, =pi becomes [u]; if the vowel is non-high (mid or closed), =pi becomes [o] (if the preceding vowel is nasalized, then the resulting vowel is also nasalized): hi=pi=kte, "they will arrive here", [hiukte]; yatkáŋ=pi=na, "they drank it and...", [jatkə̃õna].[9]

Lakota also exhibits some traces of sound symbolism among fricatives, where the point of articulation changes to reflect intensity: zí, "it's yellow", ží, "it's tawny", ǧí, "it's brown".[11] (Compare with the similar examples in Mandan.)

Orthographies, standardization, and teaching materials

editSeveral orthographies as well as ad hoc spelling are used to write the Lakota language, with varying perspectives on whether standardization should be implemented.[12][13][14] In 2002, Rosebud Cultural Studies teacher Randy Emery argued that standardization of the language could cause problems "because the language is utilized diversely. If standardization is determined to be the approach... then the question is whose version will be adopted? This will cause dissent and politics to become a factor in the process."[15]

Also in 2002, Sinte Gleska University rejected a partnership with the European-owned Lakota Language Consortium.[15] Sinte Gleska uses the orthography developed by Albert White Hat,[16] which on December 13, 2012, was formally adopted by the Rosebud Sioux Tribe per Tribal Resolution No. 2012–343. This resolution also banned the Lakota Language Consortium and its "Czech orthography" from the reservation and its educational system.[17] This ban was a response to a series of protests by community members and grassroots language preservation workers, at Rosebud and other Lakota communities, against the Lakota Language Consortium (LLC).[15][18] Despite its name, the LLC is an organization formed by two Europeans.[18] Concerns arose due to the LLC's promotion of their New Lakota Dictionary, websites and other Internet projects aimed at revising and standardizing their new spelling of the Lakota language. "Lakota first language speakers and Lakota language teachers criticize the "Czech orthography" for being overloaded with markings and – foremost – for the way it is being brought into Lakota schools"; it has been criticized as "neocolonial domination."[18] Sonja John writes that "The new orthography the Czech linguist advocates resembles the Czech orthography – making it easier for Czech people to read. The Europeans predominantly use the internet to give the impression that this "Czech orthography" is a Lakota product and the standard for writing Lakota."[19] "The Rosebud Sioux Tribe was the first of the Lakota tribes to take legal action against the self-authorizing practices the LLC committed by utilizing names of Lakota language experts without their consent to obtain funding for their projects."[20] Rosebud Resolution No. 2008–295 goes further and compares these actions to what was done to children taken from their families by the residential schools.[20]

In 2006 some of the Lakota language teachers at Standing Rock chose to collaborate with Sitting Bull College, and the Lakota Language Consortium (LLC), with the aim of expanding their language curriculum. Teachers at Standing Rock use several different orthographies.[21] Language activists at Standing Rock also refer to it as simply the "SLO" or even "Suggested Lakota Orthography."[21] Tasha Hauff writes,

Choosing a writing system, or orthography, is often a serious point of contention in Indigenous communities engaging in revitalization work (Hinton, 2014). While writing a traditionally oral language can itself be considered a colonial act, standardizing a writing system is fraught with political as well as pedagogical complications. Because teachers at Standing Rock were in need of language-teaching materials, and the LLC was one of the few organizations developing such resources, Standing Rock adopted the new orthography, but not without resistance from members of the community. ... The new writing system at Standing Rock was often criticized or even rejected within the community. Some fluent speakers at Standing Rock have not accepted the new writing system. There are some who continue to work in language education and who use the LLC materials but do not write in the orthography. These are usually Elders who remain in the habit of writing the way they learned. A few people at Standing Rock, however, have been offended by the notion of a standard way of writing Lakota/Dakota, especially one that seems unlike any of the systems used by Elders. Community members have been particularly wary of the SLO ["Standard Lakota Orthography"], which appears to be developed by outsiders who are not fluent speakers and would require considerable study for a fluent speaker to use.[21]

In 2013 Lakota teachers at Red Cloud Indian School on Pine Ridge Indian Reservation discussed their use of orthography for their K–12 students as well as adult learners. The orthography used at Red Cloud "is meant to be more phonetic than other orthographies... That means there are usually more 'H's than other versions. While many orthographies use tipi... Red Cloud spells it thípi." He continues, "the orthography also makes heavy use of diacritical marks... that is not popular among some educators and academics". Delphine Red Shirt, an Oglala Lakota tribal member and a lecturer on languages at Stanford University, disagrees and prefers a Lakota orthography without diacritical marks. "I'm very against any orthography that requires a special keyboard to communicate," she said. First language speaker and veteran language teacher at Red Cloud, the late Philomine Lakota, had similar concerns with the orthography, and argues against changing the spelling forms she learned from her father. However, she did consider that, a shared curriculum could "create consistency across the region and encourage the long-term viability of the language. However, Philomine is also cognizant that it will take more than a school curriculum to preserve the language."[22] She added, "In order for a language to survive, it can't simply be taught from the top. A language is a living thing and students need to breathe life into it daily; talking with friends, family and elders in Lakota".[22]

In 2018, at the Cheyenne River Indian Reservation, Lakota speaker Manny Iron Hawk and his wife Renee Iron Hawk discussed opening an immersion school and the difficulties around choosing an orthography to write Lakota; Mr. Iron Hawk voiced support for the LLC (SLO) Orthography, saying it was accessible to second language learners, but know not all agreed with him.[23] Others in the community voiced a preference for the tribe creating their own orthography. While Mr. Iron Hawk supports this approach, Renee Iron Hawk also expressed a sense of urgency, saying "We should just use what we have, and then fix and replace it, but we need to start speaking it now". The Iron Hawks both agreed that too much time has been spent arguing over which orthography to use or not use, and not enough time is spent teaching and speaking the language.[23]

On May 3, 2022, the Tribal Council of the Standing Rock Sioux, in a near-unanimous vote, banished the Lakota Language Consortium (and specifically, LLC linguist Jan Ullrich and co-founder Wilhelm Meya) from ever again setting foot on the reservation. The council's decision was based on the LLC's history with not only the Standing Rock community, but also with at least three other communities that also voiced concerns about Meya and the LLC, "saying he broke agreements over how to use recordings, language materials and historical records, or used them without permission."[24][25]

LLC alphabet

editThe "Standard Lakota Orthography" as the LLC calls it, is in principle phonemic, which means that each character (grapheme) represents one distinctive sound (phoneme), except for the distinction between glottal and velar aspiration, which is treated phonetically.

Lakota vowels are ⟨a, e, i, o, u⟩ nasal vowels are aŋ, iŋ, uŋ. Pitch accent is marked with an acute accent: ⟨á, é, í, ó, ú, áŋ, íŋ, úŋ⟩ on stressed vowels (which receive a higher tone than non-stressed ones)[26]

The following consonants approximate their IPA values: ⟨b, g, h, k, l, m, n, ŋ, p, s, t, w, z⟩. ⟨Y⟩ has its English value of /j/. An apostrophe, ⟨'⟩, is used for the glottal stop.

A caron is used for sounds, other than /ŋ/, which are not written with Latin letters in the IPA: ⟨č⟩ /tʃ/, ⟨ǧ⟩ /ʁ/, ⟨ȟ⟩ /χ/, ⟨š⟩ /ʃ/, ⟨ž⟩ /ʒ/. Aspirates are written with ⟨h⟩: ⟨čh, kh, ph, th,⟩ and velar frication with ⟨ȟ⟩: ⟨kȟ, pȟ, tȟ.⟩ Ejectives are written with an apostrophe: ⟨č', ȟ', k', p', s', š', t'⟩.

The spelling used in modern popular texts is often written without diacritics. Besides failing to mark stress, this also results in the confusion of numerous consonants: /s/ and /ʃ/ are both written ⟨s⟩, /h/ and /χ/ are both written ⟨h⟩, and the aspirate stops are written like the unaspirates, as ⟨p, t, c, k⟩.

|

All digraphs (i.e. characters created by two letters, such as kh, kȟ, k') are treated as groups of individual letters in alphabetization. Thus for example the word čhíŋ precedes čónala in a dictionary.

Curley alphabet

editIn 1982, Lakota educator Leroy Curley (1935–2012) devised a 41-letter circular alphabet.[27]

Grammar

editWord order

editThe basic word order of Lakota is subject–object–verb, although the order can be changed for expressive purposes (placing the object before the subject to bring the object into focus or placing the subject after the verb to emphasize its status as established information). It is postpositional, with adpositions occurring after the head nouns: mas'óphiye él, "at the store" (literally 'store at'); thípi=kiŋ ókšaŋ, "around the house" (literally 'house=the around') (Rood and Taylor 1996).

Rood and Taylor (1996) suggest the following template for basic word order. Items in parentheses are optional; only the verb is required. It is therefore possible to produce a grammatical sentence that contains only a verb.

(interjection) (conjunction) (adverb(s)) (nominal) (nominal) (nominal) (adverb(s)) verb (enclitic(s)) (conjunction)

Interjections

editWhen interjections are used, they begin the sentence or end it. A small number of interjections are used only by one gender, for instance the interjection expressing disbelief is ečéš for women but hóȟ for men; for calling attention women say máŋ while men use wáŋ. Most interjections, however, are used by both genders.

Conjunctions

editIt is common for a sentence to begin with a conjunction. Both čhaŋké and yuŋkȟáŋ can be translated as and; k’éyaš is similar to English but. Each of these conjunctions joins clauses. In addition, the conjunction na joins nouns or phrases.

Adverbs, postpositions and derived modifiers

editLakota uses postpositions, which are similar to English prepositions, but follow their noun complement. Adverbs or postpositional phrases can describe manner, location, or reason. There are also interrogative adverbs, which are used to form questions.

Synonymity in the postpositions él and ektá

editTo the non-Lakota speaker, the postpositions él and ektá sound like they can be interchangeable, but although they are full synonyms of each other, they are used in different occasions. Semantically (word meaning), they are used as locational and directional tools. In the English language they can be compared to prepositions like "at", "in", and "on" (when used as locatives) on the one hand, and "at", "in", and "on" (when used as directionals), "to", "into", and "onto", on the other. (Pustet 2013)

A pointer for when to use él and when to use ektá can be determined by the concepts of location (motionless) or motion; and space vs. time. These features can produce four different combinations, also called semantic domains, which can be arranged as follows (Pustet 2013):

- space / rest: "in the house" [thípi kiŋ él] (This sentence is only describing location of an object, no movement indicated)

- space / motion: "to the house [thípi kiŋ ektá] (This sentence is referring to movement of a subject, it is directional in nature)

- time / rest: "in the winter" [waníyetu kiŋ él] (This sentence refers to a static moment in time, which happens to be during winter)

- time / motion: "in/towards the winter" [waníyetu kiŋ ektá] (Pustet 2013) (This sentence is delegated to time, but time which is soon to change to another season)

Summed up, when a context describes no motion, él is the appropriate postposition; when in motion, ektá is more appropriate. They are both used in matters of time and space.

Nouns and pronouns

editAs mentioned above, nominals are optional in Lakota, but when nouns appear the basic word order is subject–object–verb. Pronouns are not common, but may be used contrastively or emphatically.

Lakota has four articles: waŋ is indefinite, similar to English a or an, and kiŋ is definite, similar to English the. In addition, waŋží is an indefinite article used with hypothetical or irrealis objects, and k’uŋ is a definite article used with nouns that have been mentioned previously.

Demonstratives

editThere are also nine demonstratives, which can function either as pronouns or as determiners.

| Distance from speaker | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| near the speaker | near the listener | away from both speaker and listener | |

| singular | lé | hé | ká |

| dual | lenáos | henáos | kanáos |

| plural | lená | hená | kaná |

Verbs

editVerbs are the only word class that are obligatory in a Lakota sentence. Verbs can be active, naming an action, or stative, describing a property. (In English, such descriptions are usually made with adjectives.)

Verbs are inflected for first-, second- or third person, and for singular, dual or plural grammatical number.

Morphology

editVerb inflection

editThere are two paradigms for verb inflection. One set of morphemes indicates the person and number of the subject of active verbs. The other set of morphemes agrees with the object of transitive action verbs or the subject of stative verbs.[9]

Most of the morphemes in each paradigm are prefixes, but plural subjects are marked with a suffix and third-person plural objects with an infix.

First person arguments may be singular, dual, or plural; second or third person arguments may be singular or plural.

| singular | dual | plural | |

|---|---|---|---|

| first person | wa- | uŋ(k)- | uŋ(k)- ... -pi |

| second person | ya- | ya- ... -pi | |

| third person | unmarked | -pi |

Examples: máni "He walks." mánipi "They walk."

| singular | dual | plural | |

|---|---|---|---|

| first person | ma- | uŋ(k)- | uŋ(k)- ... -pi |

| second person | ni- | ni- ... -pi | |

| third person | unmarked | -pi |

| singular | dual | plural | |

|---|---|---|---|

| first person | ma- | uŋ(k)- ... -pi | |

| second person | ni- | ni- ... -pi | |

| third person | unmarked | -wicha- |

Example: waŋwíčhayaŋke "He looked at them" from waŋyáŋkA "to look at something/somebody".

Subject and object pronouns in one verb

If both the subject and object need to be marked, two affixes occur on the verb. Below is a table illustrating this. Subject affixes are marked in italics and object affixes are marked in underline. Some affixes encompass both subject and object (such as čhi- ...). The symbol ∅ indicates a lack of marking for a particular subject/object (as in the case of 3rd Person Singular forms). Cells with three forms indicate Class I, Class II, and Class III verb forms in this order.

| me | you (sg.) | him/her/it; them (inanimate) | us | you (pl.) | them (animate) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | čhi-1 ... | wa∅- ... bl∅- ... m∅- ... |

čhi- ... -pi | wičhawa- ... wičhabl- ... wičham- ... | ||

| you (sg.) | maya- ... mayal-2 ... mayan- ... |

ya∅- ... l∅- ... n∅- ... |

uŋya- ... -pi uŋl- ... -pi uŋn- ... -pi |

wičhaya- ... wičhal- ... wičhan- ... | ||

| he/she/it | ma∅- ... | ni∅- ... | ∅∅- ... | uŋ(k)∅- ... -pi | ni∅- ... -pi | wičha∅- ... |

| we | uŋni-3 ... -pi | uŋ(k)∅- ... -pi | uŋni- ... -pi | wičhauŋ(k)-4 ... -pi | ||

| you (pl.) | maya- ... -pi mayal- ... -pi mayan- ... -pi |

ya∅- ... -pi l∅- ... -pi n∅- ... -pi |

uŋya- ... -pi5 uŋl- ... -pi uŋn- ... -pi |

wičhaya- ... -pi wičhal- ... -pi wičhan- ... -pi | ||

| they | ma- ... -pi | ni- ... -pi | ... -∅pi | uŋ- ... -pi | ni- ... -pi | wičha- ... -pi |

- 1 The affix čhi- covers cases where I-subject and you-object occurs in transitive verbs.

- 2 Class II and Class III verbs have irregular yal- and yan- respectively.

- 3 These prefixes are separated when uŋ(k)- must be prefixed while ni- et al. must be infixed.

Example: uŋkánipȟepi "We are waiting for you" from apȟé "to wait for somebody".

- 4 uŋ(k)- precedes all affixes except wičha-. In the last column, verbs which require uŋ(k)- to be prefixed are more complex because of competing rules: uŋ(k)- must be prefixed, but must also follow wičha-. Most speakers resolve this issue by infixing wičhauŋ(k) after the initial vowel, then repeating the initial vowel again.

Example: iwíčhauŋkičupi "We took them" from ičú "to take something/somebody".

- 5 Since the suffix -pi can appear only once in each verb, but may pluralize either subject or object (or both), some ambiguity exists in the forms: uŋ- ... -pi, uŋni- ... -pi, and uŋya-/uŋl-/uŋn- ... -pi.

Enclitics

editLakota has a number of enclitic particles which follow the verb, many of which differ depending on whether the speaker is male or female.

Some enclitics indicate the aspect, mood, or number of the verb they follow. There are also various interrogative enclitics, which in addition to marking an utterance as a question show finer distinctions of meaning. For example, while he is the usual question-marking enclitic, huŋwó is used for rhetorical questions or in formal oratory, and the dubitative wa functions somewhat like a tag question in English (Rood and Taylor 1996; Buchel 1983). (See also the section below on men and women's speech.)

Men's and women's speech

editA small number of enclitics (approximately eight) differ in form based on the gender of the speaker. Yeló (men) ye (women) mark mild assertions. Kštó (women only according to most sources) marks strong assertion. Yo (men) and ye (women) mark neutral commands, yetȟó (men) and nitȟó (women) mark familiar, and ye (both men and women) and na mark requests. He is used by both genders to mark direct questions, but men also use hųwó in more formal situations. So (men) and se (women) mark dubitative questions (where the person being asked is not assumed to know the answer).

While many native speakers and linguists agree that certain enclitics are associated with particular genders, such usage may not be exclusive. That is, individual men sometimes use enclitics associated with women, and vice versa (Trechter 1999).

| Enclitic | Meaning | Example[28] | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| hAŋ | continuous | yá-he | "was going" |

| pi | plural | iyáyapi | "they left" |

| la | diminutive | záptaŋla | "only five" |

| kA | attenuative | wašteke | "somewhat good" |

| ktA | irrealis | uŋyíŋ kte | "you and I will go" (future) |

| šni | negative | hiyú šni | "he/she/it did not come out" |

| s’a | repeating | eyápi s’a | "they often say" |

| séčA | conjecture | ú kte séče | "he might come" |

| yeló | assertion (masc) | blé ló | "I went there (I assert)" |

| yé | assertion (fem) | hí yé | "he came (I assert)" |

| he | interrogative | Táku kȟoyákipȟa he? | "What do you fear?" |

| huŋwó | interrogative (masc. formal) | Tókhiya lá huŋwó? | "Where are you going?" |

| huŋwé | interrogative (fem. formal, obsolete) | Hé tákula huŋwé? | "What is this little thing?" |

| waŋ | dubitative question | séča waŋ | "can it be as it seems?" |

| škhé | evidential | yá-ha škhé | "he was going, I understand" |

| kéye | evidential (hearsay) | yápi kéye | "they went, they say" |

Ablaut

edit- All examples are taken from the New Lakota Dictionary.

The term "ablaut" refers to the tendency of some words to change their final vowel in certain situations. Compare these sentences.

- Šúŋka kiŋ sápa čha waŋbláke.

- Šúŋka kiŋ sápe.

- Šúŋka kiŋ sápiŋ na tȟáŋka.

The last vowel in the word "SápA" changed each time. This vowel change is called "ablaut". Words which undergo this change are referred to as A-words, since, in dictionary citations, they are written ending in either -A or -Aŋ. These words are never written with a final capital letter in actual texts. Derivatives of these words generally take the ablaut as well, however there are exceptions.

There are three forms for ablauted words: -a/-aŋ, -e, -iŋ. These are referred to as a/aŋ-ablaut, e-ablaut, and iŋ-ablaut respectively. Some words are ablauted by some and not others, like "gray" hóta or hótA. Ablaut always depends on what word follows the ablauted word.

A/aŋ-ablaut

editThis is the basic form of the word, and is used everywhere in which the other forms are not utilized.

E-ablaut

editThere are two cases in which e-ablaut is used.

- Last word in the sentence

- Followed by a word which triggers e-ablaut

1. Last word in sentence

edit- Examples

- Héčhiya yé He went there. (e-ablaut of the verb yÁ)

- Yúte She ate it. (e-ablaut of the verb yútA)

- Thípi kiŋ pahá akáŋl hé. The house stands on a cliff. (e-ablaut of the verb hÁŋ)

2. Followed by a word which triggers e-ablaut

editThere are three classes of words which trigger e-ablaut

- various enclitics, such as ȟča, ȟčiŋ, iŋčhéye, kačháš, kiló, kštó, któk, lakȟa, -la, láȟ, láȟčaka, ló, séčA, sékse, s’eléčheča, so, s’a, s’e, šaŋ, šni, uŋštó

- some conjunctions and articles, such as kiŋ, kiŋháŋ, k’éaš, k’uŋ, eháŋtaŋš

- some auxiliary verbs, such as kapíŋ, kiníča (kiníl), lakA (la), kúŋzA, phiča, ši, wačhíŋ, -yA, -khiyA

- Examples

- Škáte šni. He did not play. (enclitic)

- Škáte s’a. He plays often. (enclitic)

- Škáte ló. He plays. (enclitic (marking assertion))

- Okȟáte háŋtaŋ... If it is hot... (conjunctive)

- Sápe kiŋ The black one (definite article)

- Glé kúŋze. He pretended to go home. (auxiliary verb)

- Yatké-phiča. It is drinkable. (auxiliary verb)

Iŋ-ablaut

editThe iŋ-ablaut (pronounced i by some) occurs only before the following words:

- ktA (irrealis enclitic)

- yetȟó (familiar command enclitic)

- na, naháŋ (and)

- naíŋš (or, and or)

- yé (polite request or entreaty enclitic)

- Examples

- Waŋyáŋkiŋ yetȟó. Take a look at this, real quick.

- Yíŋ kte. She will go.

- Skúyiŋ na wašté. It was sweet and good.

- Waŋyáŋkiŋ yé. Please, look at it.

Phrases

edit"Háu kȟolá", literally "Hello, friend", is the most common greeting, and was transformed into the generic motion picture American Indian "How!", just as the traditional feathered headdress of the Teton was "given" to all movie Indians. As háu is the only word in Lakota which contains a diphthong, /au/, it may be a loanword from a non-Siouan language.[9]

Language revitalization efforts

editAssimilating Indigenous peoples into the expanding American society of the late 19th and early 20th centuries depended on suppression or full eradication of each tribe's unique language as the central aspect of its culture. Indian residential schools in the US and Canada that separated Indigenous children from their parents and relatives enforced this assimilation process with beatings and other forms of violence for speaking tribal languages(Powers).[full citation needed] The Lakota language survived this suppression. "Lakota persisted through the recognized natural immersion afforded by daily conversation in the home, the community at reservation-wide events, even in texts written in the form of letters to family and friends. people demonstrated their cultural resilience through the positive application of spoken and written Lakota." (Powers)[full citation needed]

Even so, employment opportunities were based on speaking English; a Lakota who was bilingual or spoke only English was more likely to be hired.[5]

In 1967, the Red Cloud Indian School at Pine Ridge began offering Lakota language classes. This was over two decades before the Native American Languages Act of 1990.[29]

In the mid-1970s the Rosebud Reservation established their Lakota Language and Culture department at the Sinte Gleska University under the chairmanship of Ben Black Bear, Jr., who employed textbooks and orthography developed by the Colorado University Lakota Project (CULP). A few years later Black Bear was replaced as a chair of the department by Albert White Hat, who discontinued the use of the Colorado University textbooks. In 1992 White Hat published a textbook with his own orthography, for use at all levels of language learning on Rosebud. Sinte Gleska University now uses the orthography developed by Albert White Hat.[16]

In 2002 Sinte Gleska University rejected the Lakota Language Consortium invitation to support their organization. Rosebud Cultural Studies teacher Randy Emery spoke to the Lakota Journal, stating, "The Lakota Language Consortium has created the misleading impression that Sinte Gleska University is one of the schools that supports their organization," and that the LLC had circulated a document to this effect with other misleading information about the state of the language, "The (LLC) documentation strongly implies that there are no fluent speakers younger than the elder age group and the presentation implies that the Lakota cannot deal with the problem themselves; therefore outside help must be brought in to lead the program. This appears to us as a sugar coated attack on sovereignty".[15]

In 2008, the Red Cloud School at Pine Ridge launched their Lakota language curriculum for K–12 students.[29] In November 2012, the incoming president of the Oglala Sioux Tribe, Bryan Brewer, announced that he intended "to lead a Lakota Language Revitalization Initiative that will focus on the creation and operation of Lakota language immersion schools and identifying all fluent Lakota speakers."[30] A Lakota language immersion daycare center is scheduled to open at Pine Ridge.[31] Also in 2012, Lakota immersion classes were provided for children in an experimental program at Sitting Bull College on the Standing Rock Reservation, where children speak only Lakota for their first year.[32] Tom Red Bird is a Lakota teacher at the program who grew up on the Cheyenne River Reservation. He believes in the importance of teaching the language to younger generations as this would close the gap in the ages of speakers.[33] In 2014, it is estimated that about five percent of children age four to six on Pine Ridge Indian Reservation speak Lakota.[34] Language Revitalization efforts continued to be strengthened by the establishment of several independent, grassroots Lakota language immersion schools and camps, such as those at the Dakota Access Pipeline protests camps at Standing Rock in 2016.[35]

On May 3, 2022, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Council passed Resolution Number 150-22, which, along with banishing the LLC, contains provisions to protect the Nation's intellectual property rights and data sovereignty.[24][25]

It reclaimed copyrights over all language materials created by the consortium and called for their immediate return, to be placed in the care of "the first-language speakers and knowledge-keepers in our communities."[24][25]

Lakota Language Education Program (LLEAP)

editIn 2011, Sitting Bull College (Fort Yates, North Dakota, Standing Rock) and the University of South Dakota began degree programs to create effective Lakota language teachers. By earning a Bachelor of Arts in education at the University of South Dakota or a Bachelor of Science in education at Sitting Bull College, students can major in "Lakota Language Teaching and Learning" as part of the Lakota Language Education Action Program, or LLEAP.

LLEAP is a four-year program designed to create at least 30 new Lakota language teachers by 2014, and was funded by $2.4 million in grants from the U.S. Department of Education. At the end of the initial phase, SBC and USD will permanently offer the Lakota Language Teaching and Learning degree as part of their regular undergraduate Education curriculum. The current LLEAP students' tuition and expenses are covered by the grant from the U.S. Department of Education. LLEAP is the first program of its kind, offering courses to create effective teachers in order to save a Native American language from going extinct, and potentially educate the 120,000 prospective Lakota speakers in the 21st century.[36]

Government support

editIn 1990, Senator Daniel Inouye (D-HI) sponsored the Native American Languages Act in order to preserve, protect, and promote the rights and freedoms of Native people in America to practice, develop and conduct business in their native language. This law, which took effect on October 30, 1990, reversed over 200 years of American policy that would have otherwise eliminated the indigenous languages of the United States. This legislation gave support to tribal efforts to fund language education programs.[37]

Self-study external links

editSome resources exist for self-study of Lakota by a person with no or limited access to native speakers. Here is a collection of selected resources currently available:

Additional print and electronic materials have been created by the immersion program on Pine Ridge.[examples needed]

- Lakota: A Language Course for Beginners by Oglala Lakota College (ISBN 0-88432-609-8) (with companion 15 CDs/Tapes) (high school/college level)

- Reading and Writing the Lakota Language by Albert White Hat Sr. (ISBN 0-87480-572-4) (with companion 2 tapes) (high school/college level)

- University of Colorado Lakhota Project: Beginning Lakhota, vol. 1 & 2 (with companion tapes), Elementary Bilingual Dictionary and Graded Readings, (high school/college level)

- Lakota Dictionary: Lakota-English/English-Lakota, New Comprehensive Edition by Eugene Buechel, S.J. & Paul Manhart (ISBN 0-8032-6199-3)

- English-Lakota Dictionary by Bruce Ingham, RoutledgeCurzon, ISBN 0-7007-1378-6

- A Grammar of Lakota by Eugene Buechel, S.J. (OCLC 4609002; professional level)

- The article by Rood & Taylor, in[9] (professional level)

- Dakota Texts by Ella Deloria (a bilingual, interlinear collection of folktales and folk narratives, plus commentaries). (University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 0-8032-6660-X; professional level) (Note: the University of South Dakota edition is monolingual, with only the English renditions.)

- A "Lakota Toddler" app designed for children ages 2–9 is available for the iPhone.[38]

- Matho Waunsila Tiwahe: The Lakota Berenstain Bears. DVD of 20 episodes of The Berenstain Bears, dubbed in Lakota with fluent Native speakers.

Lakota influences in English

editJust as people from different regions of countries have accents, Lakota who speak English have some distinct speech patterns. These patterns are displayed in their grammatical sequences and can be heard through some phonological differences. These unique characteristics are also observed in Lakota youth, even those who only learned English.[39]

Notes

edit- ^ a b Lakota at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

- ^ "Ella Cara Deloria". Association for Women in Science. Association for Women in Science. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ "Winged Messenger Nations: Birds in American Indian Oral Tradition: Albert White Hat Sr. & Francis Cut". The Winged Messenger Project. The Winged Messenger Project. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ Sneve, Paul (2013). "Anamnesis in the Lakota Language and Lakota Concepts of Time and Matter". Anglican Theological Review. 95 (3): 487–493.

- ^ a b Andrews, Thomas G (2002). "Turning the Tables on Assimilation: Oglala Lakotas and the Pine Ridge Day Schools 1889–1920s". Western Historical Quarterly. 33 (4): 407–430. doi:10.2307/4144766. JSTOR 4144766.

- ^ Walker, J.R.; DeMallie, R.J.; Jahner, E. (1980). Lakota Belief and Ritual. Bison books. U of Nebraska Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-8032-9867-5. Retrieved December 18, 2021.

- ^ Little, John A. (May 2020). Vietnam Akíčita: Lakota and Dakota Military Tradition in the Twentieth Century (PhD thesis). University of Minnesota. pp. 58–64.

- ^ Elementary Bilingual Dictionary English–Lakhóta Lakhóta–English (1976) CU Lakhóta Project University of Colorado

- ^ a b c d e f g h Rood, David S., and Taylor, Allan R. (1996). Sketch of Lakhota, a Siouan Language, Part I. Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 17 (Languages), pp. 440–482.

- ^ a b (2004). Lakota letters and sounds.

- ^ Mithun, Marianne (2007). The Languages of Native North America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 33.

- ^ "Language Materials Project: Lakota". UCLA. Archived from the original on 30 December 2010. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- ^ Powers, William K. (1990). "Comments on the Politics of Orthography". American Anthropologist. 92 (2): 496–498. doi:10.1525/aa.1990.92.2.02a00190. JSTOR 680162.

- ^ Palmer, 2

- ^ a b c d Thunder Hawk, Cal (Aug 30, 2002). "Sinte Gleska University to reject Lakota Language Consortium membership". Lakota Journal - Around Lakota Country. Archived from the original on 2021-12-15. Retrieved 2021-12-15.

Emery said, based on their review of "Lakota Language Revitalization: General Overview," a document published by the LLC and widely circulated in Lakota country by LLC this spring, Lakota Studies will not recommend SGU participation in the consortium. He continued, "The presentation suggests that a goal for the program is standardization of the language. We feel that this approach will cause problems because the language is utilized diversely. If standardization is determined to be the approach of the organization, then the question is whose version will be adopted? This will cause dissent and politics to become a factor in the process."

- ^ a b Arlene B. Hirschfelder (1995). Native Heritage: Personal Accounts by American Indians, 1790 to the Present. VNR AG. ISBN 978-0-02-860412-1.

- ^ John, Sonja (2018). "Orality Overwritten: Power Relations in Textualization". In Fink, Sebastian; Lang, Martin; Schretter, Manfred (eds.). Mehrsprachigkeit. Vom Alten Orient bis zum Esperanto (PDF). Zaphon, Münster www.zaphon.de. p. 98. ISBN 978-3-96327-004-8.

In a next step, the Rosebud Sioux Tribe adopted Tribal Resolution No. 2012–343, on December 13, 2012, declaring Albert White Hat's Lakota orthography to be the standard on the Rosebud reservation: "THEREFORE BE IT RESOLVED, the Rosebud Sioux Tribe hereby adopts the Official Rosebud Sioux Tribe Lakota Language Orthography recommended by the Rosebud Sioux Tribe Education Department." The tribe thus banned the LLC and its "Czech orthography" from the reservation and its educational system.

- ^ a b c John, Sonja (2018). "Orality Overwritten: Power Relations in Textualization". In Fink, Sebastian; Lang, Martin; Schretter, Manfred (eds.). Mehrsprachigkeit. Vom Alten Orient bis zum Esperanto (PDF). Zaphon, Münster www.zaphon.de. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-3-96327-004-8.

- ^ John, Sonja (2018). "Orality Overwritten: Power Relations in Textualization". In Fink, Sebastian; Lang, Martin; Schretter, Manfred (eds.). Mehrsprachigkeit. Vom Alten Orient bis zum Esperanto (PDF). Zaphon, Münster www.zaphon.de. p. 73. ISBN 978-3-96327-004-8.

- ^ a b John, Sonja (2018). "Orality Overwritten: Power Relations in Textualization". In Fink, Sebastian; Lang, Martin; Schretter, Manfred (eds.). Mehrsprachigkeit. Vom Alten Orient bis zum Esperanto (PDF). Zaphon, Münster www.zaphon.de. pp. 97–98. ISBN 978-3-96327-004-8.

In addition the residential schools aimed at separating children from the influence of their parents in order to educate them in the non-Native way.

WHEREAS, issues of non-native American sources entering the reservation and school systems with their own welfare in mind; and their entities are utilizing individuals' names without consent for the sake of contributors lists to mislead the public and further receive support of unsuspecting school districts, school boards, or programs

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED, that any individual, entity, or any other source that wishes to research or document any information regarding the Lakota Language, History, and Culture must first go through the approval of the Rosebud Sioux Tribal Council and Administration or designated entity such as Education Committee, RST Tribal Education, local Collaborations Groups, or Advisory Committee. - ^ a b c Hauff, Tasha. "Beyond Colors, Numbers and Animals". JSTOR. University of Minnesota Press. Retrieved December 16, 2021.

- ^ a b Simmons-Ritchie, Daniel. "Red Cloud School Fights to Save Lakota Language". Native Times. Rapid City Journal. Retrieved December 16, 2021.

- ^ a b Rust, Jody (8 August 2018). "Immersion School Seeks to spark everyday use of Lakota language and preserve cultural identity". West River Eagle. Retrieved December 16, 2021.

- ^ a b c Brewer, Graham Lee (3 June 2022). "Lakota elders helped a white man preserve their language. Then he tried to sell it back to them". NBC News. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ^ a b c Standing Rock Tribal Council (3 June 2022). "Standing Rock banishment resolution". NBC News. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ^ Cho, Taehong. "Some phonological and phonetic aspects of stress and intonation in Lakhota: a preliminary report", Published as a PDF at :humnet.ucla.edu "Lakhota", Linguistics, UCLA

- ^ "Ten studies in the alphabet of the Lakota language". Lakota Times. 13 November 2008.

- ^ Deloria, Ella (1932). Dakota Texts. New York: G.E. Stechert.

- ^ a b "Celebrating 125 Years". Red Cloud Country. Spring 2013. Retrieved 2021-12-17. Note: Prior to 1969, the school was known as Holy Rosary.

- ^ Cook, Andrea (2012-11-16). "Brewer pledges to preserve Lakota language". Retrieved 2012-11-20.

- ^ Aaron Moselle (November 2012). "Chestnut Hill native looks to revitalize "eroded" American Indian language". NewsWorks, WHYY. Archived from the original on 2013-05-18. Retrieved 2012-11-29.

- ^ Donovan, Lauren (2012-11-11). "Learning Lakota, one word at a time". Bismarck Tribune. Bismarck, ND. Retrieved 2012-11-20.

- ^ DONOVAN, L (2012). "Tribal College Program Teaches Lakota Language to Youngsters". Community College Week. 25 (9): 10.

- ^ Doering, Christopher (2014-06-19). "Indians press for funds to teach Native languages". Argus Leader. Retrieved 2014-06-28.

- ^ Ecoffey, Brandon (2016-09-01). "School Opens In Protector Camp". Retrieved 2021-12-10.

- ^ Campbell, Kimberlee (2011). "Sitting Bull Offers New Lakota Curriculum". Tribal College Journal. 22 (3): 69–70.

- ^ Barringer, Felicity (8 January 1991). "Faded but Vibrant, Indian Languages Struggle to Keep Their Voices Alive". The New York Times. Retrieved 2013-10-25.

- ^ "App Shopper: Lakota Toddler (Education)". Retrieved 2012-09-12.

- ^ Flanigan, Olson. "Language Variation Among Native Americans: Observations of Lakota English". Journal of English Linguistics. Retrieved 2013-10-25.

References

edit- Palmer, Jessica Dawn. The Dakota Peoples: A History of Dakota, Lakota, and Nakota through 1863.Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2008. ISBN 978-0-7864-3177-9.

- Rood, David S. and Allan R. Taylor. (1996). Sketch of Lakhota, a Siouan Language. Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 17 (Languages), pp. 440–482. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution. Online version.

- Pustet, Regina (2013). "Prototype Effects in Discourse and the Synonymy Issue: Two Lakota Postpositions". Cognitive Linguistics. 14 (4): 349–78. doi:10.1515/cogl.2003.014.

- Powers, William K (2009). "Saving Lakota: Commentary on Language Revitalization". American Indian Culture & Research Journal. 33 (4): 139–49. doi:10.17953/aicr.33.4.2832x77334756478.

- Henne, Richard B. "Verbal Artistry: A Case for Education." ANTHROPOLOGY & EDUCATION QUARTERLY no. 4 (2009): 331–349.

- Sneve, Paul (2013). "Anamnesis in the Lakota Language and Lakota Concepts of Time and Matter". Anglican Theological Review. 95 (3): 487–493.

- McGinnis, Anthony R (2012). "When Courage Was Not Enough: Plains Indians at War with the United States Army". Journal of Military History. 76 (2): 455–473.

- Andrews, Thomas G (2002). "Turning the Tables on Assimilation: Oglala Lakotas and the Pine Ridge Day Schools, 1889-1920s". Western Historical Quarterly. 33 (4): 407–430. doi:10.2307/4144766. JSTOR 4144766.

- Pass, Susan (2009). "Teaching Respect for Diversity: The Oglala Lakota". Social Studies. 100 (5): 212–217. doi:10.1080/00377990903221996. S2CID 144704897.

- Campbell, Kimberlee (2011). "Sitting Bull Offers New Lakota Curriculum". Tribal College Journal. 22 (3): 69–70.

Further reading

edit- Buechel, Eugene (1983). A Dictionary of Teton Sioux. Pine Ridge, SD: Red Cloud Indian School.

- DeMallie, Raymond J. (2001). "Sioux until 1850". In R. J. DeMallie (Ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 2, pp. 718–760). W. C. Sturtevant (Gen. Ed.). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0-16-050400-7.

- de Reuse, Willem J. (1987). "One hundred years of Lakota linguistics (1887-1987)". Kansas Working Papers in Linguistics. 12: 13–42. doi:10.17161/KWPL.1808.509. hdl:1808/509.

- de Reuse, Willem J. (1990). "A supplementary bibliography of Lakota languages and linguistics (1887-1990)". Kansas Working Papers in Linguistics. 15 (2): 146–165. doi:10.17161/KWPL.1808.441. hdl:1808/441.

- Parks, Douglas R.; & Rankin, Robert L. (2001). "The Siouan languages". In Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 1, pp. 94–114). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- Trechter, Sarah (1999). "Contextualizing the Exotic Few: Gender Dichotomies in Lakhota". In Bucholtz, M.; Liang, A. C.; Sutton, L. (eds.). Reinventing Identities. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 101–122. ISBN 0-19-512629-7.

External links

edit- Lakota Language Reclamation Project - "Open sourcing the People's language for all Lakota and Dakota people and our allies"

- Red Cloud Indian School Lakota Language Project[usurped]

- Niobrara Wocekiye Wowapi: The Niobrara Prayer Book (1991) Episcopal Church prayers in Lakota

- Our Languages: Lakota (Saskatchewan Indian Cultural Centre)

- Swadesh vocabulary lists for Lakota and other Siouan languages (from Wiktionary)

- Systemic racism in linguistics - comparison of different Lakota translations and orthographies