Lake Stevens is a city in Snohomish County, Washington, United States, that is named for the lake it surrounds. It is located 6 miles (9.7 km) east of Everett and borders the cities of Marysville to the northwest and Snohomish to the south. The city's population was 35,630 at the 2020 census.

Lake Stevens | |

|---|---|

Northeast shore of lake on which the city is located | |

| Motto(s): "One community, around the lake" | |

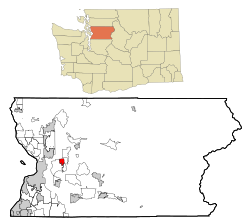

Location of Lake Stevens, Washington | |

| Coordinates: 48°1′11″N 122°3′58″W / 48.01972°N 122.06611°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Washington |

| County | Snohomish |

| Founded | 1889 |

| Incorporated | November 29, 1960 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council |

| • Mayor | Brett Gailey |

| Area | |

• Total | 9.30 sq mi (24.09 km2) |

| • Land | 9.17 sq mi (23.74 km2) |

| • Water | 0.14 sq mi (0.35 km2) |

| Elevation | 217 ft (66 m) |

| Population | |

• Total | 35,630 |

• Estimate (2022)[3] | 39,848 |

| • Density | 3,887.2/sq mi (1,500.9/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific (PST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP Code | 98258 |

| Area code | 425 |

| FIPS code | 53-37900 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1512695[4] |

| Website | lakestevenswa |

The lake was named in 1859 for territorial governor Isaac Stevens and was originally home to the Skykomish in the Pilchuck River basin. The first modern settlement on Lake Stevens was founded at the northeastern corner of the lake in 1889. It was later sold to the Rucker Brothers, who opened a sawmill in 1907 that spurred early growth in the area, but closed in 1925 after the second of two major fires. The Lake Stevens area then became a resort community before developing into a commuter town in the 1960s and 1970s.

Lake Stevens was incorporated as a city in 1960, following an exodus of businesses from the downtown area to a new shopping center. The city has since grown through annexations to encompass most of the lake, including the original shopping center, and quadrupled in population from 2000 to 2010. A revitalized downtown area is planned alongside new civic buildings in the 2020s.

History

editLake Stevens was named in 1859 for territorial governor Isaac Stevens and was originally listed as "Stevens Lake" on early maps.[5] The area around the lake was used for berry gathering by the indigenous Skykomish, who also used most of the Pilchuck River basin for hunting.[6] The first homesteads around the lake were established by emigrants in the 1880s, beginning with Joseph William Davison's 160-acre (0.65 km2) claim along the east shore filed in 1886.[7] A two-block townsite at the northeast end of the lake named "Outing" was claimed on October 8, 1889, by Charles A. Missimer and platted the following year.[8] The construction of the Seattle, Lake Shore and Eastern Railway along the eastern side of the Pilchuck River Valley in 1889 spurred the creation of more settlements in the area. Among them were Machias in 1890, which was followed by Hartford (originally named "Ferry"), later a major junction for the Everett and Monte Cristo Railway completed in 1892.[9][10]

Outing was later vacated and sold between various investors before the townsite was acquired in 1905 by the Rucker Brothers, who planned to build a sawmill after a previous venture by Jacob Falconer had failed.[11] The Rucker Brothers constructed a railroad spur from Hartford and redirected the flow of Cassidy Creek, the main outlet of the lake, to prepare land for their shingle mill, which opened in 1907.[8] A plat for the town of Lake Stevens was filed by the Rucker Brothers on February 8, 1908, including a business district and residences to accommodate the mill's 250 workers.[12] The sawmill, one of the largest in the United States, was partially destroyed in a 1919 fire and later rebuilt.[13] It was permanently closed after a second fire in 1925 and dismantled, causing many residents to leave the area.[8] One of the remnants from the old mill was a locomotive that sunk in the early 1910s and was rediscovered in 1995 by a U.S. Navy training team, following a request from the local historical society.[14]

By the mid-1920s, the entire shoreline of Lake Stevens had been divided into small lots and tracts for summer homes and resorts.[12] Following the demise of the Rucker mill, Lake Stevens was primarily a resort community that drew 3,000 visitors on busy days to fish, swim, and water-ski on the lake.[15][16] While the major lakeside resorts were successful, the Lake Stevens area saw little residential and commercial development for several decades as the downtown area stagnated.[17] The first Hewitt Avenue Trestle was completed in 1939, providing an elevated highway over the Snohomish River floodplain between Everett and Cavalero Hill, with onward connections to areas around Lake Stevens.[18]

Suburban development around Lake Stevens began in the 1950s, shortly after plans were announced to build a large shopping center named Frontier Village at the intersection of two state highways west of the lake (later State Route 9 and State Route 204). Business owners in downtown Lake Stevens proposed incorporation in 1958 to prevent retailers from relocating to the new shopping center, offering local control of policing and street maintenance with no increase in taxes.[19] On November 19, 1960, Lake Stevens voted 299–40 in favor of incorporating as a city, which was certified by the state government on November 29. The town boundaries were set around downtown and included an estimated 900 residents.[13][20] The city government purchased a former post office building for use as a city hall, which included a jail that was never used due to a change in state laws.[19][20]

The development of resorts around Lake Stevens also caused water quality to deteriorate, necessitating the creation of a voluntary drainage district in 1932 to manage runoff and pollution. It was replaced in 1963 by an independent sewer district, which mandated vegetation buffers for homes and later installed a large aeration system to slow the growth of algae in the lake.[8][21] Frontier Village opened in 1960 and later expanded as State Route 9 and State Route 204 were improved through the area. A new highway bypassing downtown, State Route 92, opened at the end of the decade.[8] The area around Frontier Village was developed into a suburban commuter town in the 1970s and 1980s with the construction of several residential subdivisions.[22][23] Hewlett-Packard won approval from the county government to build a 125-acre (51 ha) manufacturing plant northwest of Lake Stevens in 1983, despite opposition from local residents looking to preserve the area's rural character.[24][25]

By the late 1990s, the city had over 5,700 residents and was among the fastest-growing cities in the state. The unincorporated areas to the west of the lake also grew to over 20,000 people, adding multi-family housing to its existing inventory of single-family neighborhoods, and rejected an attempt to build a second shopping center and commercial complex on Cavalero Hill.[11][23] Lake Stevens unsuccessfully attempted to annex the western neighborhoods in 1993, but adopted plans to create "one community around the lake" and revitalize its downtown.[11][26] The first major annexations were completed in 2006, adding 1,563 acres (633 ha) around Frontier Village and the north end of the lake.[27] From 2000 to 2010, the city quadrupled in population to nearly 30,000 people and added 5 square miles (13 km2).[28] The largest annexation, consisting of 9 square miles (23 km2) in the southwest corner of the Lake Stevens urban growth area, was completed in December 2009 and added more than 10,000 residents.[29] Further annexations of areas to the southeast of the lake are planned to complete the full encirclement of Lake Stevens.[30]

The city government adopted plans in 2018 to redevelop downtown Lake Stevens with denser housing and commercial use, including mixed-use buildings and walkable streets.[31] The former city hall in downtown was demolished in 2017 as part of an expansion for North Cove Park, with city services temporarily relocated at an adjacent building until a permanent replacement is built.[32][33] The police station was relocated to an abandoned fire station and will open a new headquarters building on Chapel Hill in the 2020s.[31][34] An earlier plan to combine city services, the police station, and a new library at a civic campus on Chapel Hill fell through after the failure of a library bond measure.[35] The 3-acre (1.2 ha) property had been acquired in 2016 and is planned to be rezoned for commercial use.[36]

Geography

editLake Stevens is located 35 miles (56 km) northeast of Seattle and 6 miles (9.7 km) northeast of Everett, between the cities of Marysville and Snohomish.[37][38] The city's boundaries are generally defined to the north by State Route 92, to the east by the Centennial Trail, to the south by 28th Street Southeast, and to the west by State Route 204.[39] According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 9.30 square miles (24.09 km2), of which 9.17 square miles (23.75 km2) is land and 0.14 square miles (0.36 km2) is water.[1] The eponymous lake is not part of the city, but is part of the unincorporated urban growth area that also covers several neighborhoods on the southeast side of the lake. The urban growth area has been sought for annexations in the early 21st century.[30][39][40]

The city lies on a plateau between the Snohomish River delta, which separates it from Everett and Ebey Island to the west, and the foothills of the Cascade Mountains.[41] It surrounds the north and east sides of Lake Stevens, the largest and deepest lake in Snohomish County, with an area of 1,040 acres (420 ha) and an average depth of 64 feet (20 m).[38][42] The lake has 7.1 miles (11.4 km) of shoreline and is fed by Lundeen Creek, Mitchell (Kokanee) Creek, and Stitch Creek. It drains into Catherine Creek, which then flows to the Pilchuck River.[43] The lake's relatively small watershed, at 4,371 acres (1,769 ha), minimizes the effect of upstream pollution but reduces flow to remove pollutants.[42] Lake Stevens installed aeration system in the 1990s to control the release of phosphorus from lake sediments, which caused unwanted algae growth.[44] Most of the shoreline is heavily developed, with little remaining native vegetation, and Lake Stevens is used for recreational fishing, swimming, boating, and skiing.[42]

Lake Stevens has two major commercial centers: downtown and Frontier Village. Downtown Lake Stevens is located on the northeastern arm of the lake and has been undergoing redevelopment since the 1990s.[45] Frontier Village is located west of the lake at the intersection of State Route 9 and State Route 204 and is a traditional suburban shopping center with strip malls and big box stores.[46] The city government also has several designated neighborhoods and planning areas: Cavalero Hill, Frontier Village, the Hartford Industrial Area, and Machias.[47]

Economy

editAs of 2018[update], Lake Stevens has an estimated workforce population of 23,393 people, of which 15,084 are employed. The largest sectors of employment are manufacturing (18%), followed by educational and health services (17%), retail (13%), and professional services (11%).[48] The majority of workers in the city commute to other areas for employment, including 20 percent to Everett, 13 percent to Seattle, and 4 percent to Bellevue. Approximately 6.3 percent of Lake Stevens residents work within the city limits.[49][50] Over 81 percent of workers commute in single-occupant vehicles, while 2 percent take public transportation and less than 10 percent use carpools.[48]

The city had 1,553 registered businesses with 4,202 total jobs, according to 2012 estimates by the U.S. Census and Puget Sound Regional Council.[51][52] The largest provider of jobs in Lake Stevens came from businesses in the services sector, at 1,595, followed by education (991) and retail (696).[52] The city's largest employer is the Lake Stevens School District, followed by aerospace manufacturer Cobalt Enterprises, which is headquartered in the Hartford industrial area and expanded its facilities in 2016.[53][54] Over 20 percent of people with jobs based in Lake Stevens live within city limits, while the rest commute from nearby cities in northern Snohomish County.[50]

Hewlett-Packard opened a large manufacturing facility on Soper Hill northwest of Lake Stevens in 1985 for its test and measurement division, following a planning dispute with the county government. The test and measurement division was later spun off into Agilent and shared its Lake Stevens facility with Solectron. The 270,000-square-foot (25,000 m2) plant had 1,000 employees at its peak, but was closed in 2002 after several rounds of layoffs.[55][56] The 133-acre (54 ha) site was later redeveloped into a suburban housing complex in the mid-2000s.[57]

Lake Stevens is home to a large retail district anchored by Frontier Village, a shopping center located at the intersection of State Route 9 and State Route 204. It was developed beginning in the 1960s and now encompasses more than 208,000 square feet (19,300 m2) of retail space, spread across several strip malls.[46] A Costco store opened in December 2022 at the intersection of State Route 9 and 20th Street Southeast with a 160,000-square-foot (15,000 m2) building, a gas station with 30 pumps, and 800 parking stalls. A development agreement was approved by the city government in December 2019 after a year of planning and several lawsuits from residents over impacts to the environment and traffic conditions.[58][59]

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 2,586 | — | |

| 1960 | 1,538 | −40.5% | |

| 1970 | 1,283 | −16.6% | |

| 1980 | 1,660 | 29.4% | |

| 1990 | 3,380 | 103.6% | |

| 2000 | 6,361 | 88.2% | |

| 2010 | 28,069 | 341.3% | |

| 2020 | 35,630 | 26.9% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[60] | |||

Lake Stevens is the fifth-largest city in Snohomish County, with an estimated population of 33,378 in 2018.[61] The city is the fastest growing in Snohomish County since 2000, increasing by 18 percent from 2010 to 2018 through new residential development in the southwest and annexation of other areas.[62][63] The city was originally the 11th largest in the county, but jumped to fifth by annexing 10,000 people in December 2009.[29]

2010 census

editAs of the 2010 census, there were 28,069 people, 9,810 households, and 7,250 families residing in the city. The population density was 3,160.9 inhabitants per square mile (1,220.4/km2). There were 10,414 housing units at an average density of 1,172.7 per square mile (452.8/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 85.1% White, 1.7% African American, 0.9% Native American, 3.6% Asian, 0.4% Pacific Islander, 3.2% from other races, and 5.1% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 8.6% of the population.[64]

There were 9,810 households, of which 45.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 56.3% were married couples living together, 11.9% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.8% had a male householder with no wife present, and 26.1% were non-families. 19.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 5.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.86 and the average family size was 3.26.[64]

The median age in the city was 32.5 years. 29.9% of residents were under the age of 18; 8.5% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 32.2% were from 25 to 44; 23% were from 45 to 64; and 6.5% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 49.9% male and 50.1% female.[64]

2000 census

editAs of the 2000 census, there were 6,361 people, 2,139 households, and 1,683 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,951.8 people per square mile (1,142.3/km2). There were 2,234 housing units at an average density of 1,036.7 per square mile (401.2/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 92.31% White, 0.60% African American, 0.91% Native American, 1.10% Asian, 0.31% Pacific Islander, 0.90% from other races, and 3.87% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 3.55% of the population.[65]

There were 2,139 households, out of which 49.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 65.5% were married couples living together, 9.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 21.3% were non-families. 15.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 5.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.96 and the average family size was 3.30.[65]

In the city, the age distribution of the population shows 33.9% under the age of 18, 6.5% from 18 to 24, 36.3% from 25 to 44, 17.6% from 45 to 64, and 5.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 32 years. For every 100 females, there were 101.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 97.0 males.[65]

The median income for a household in the city was $65,231, and the median income for a family was $68,250. Males had a median income of $51,536 versus $30,239 for females. The per capita income for the city was $22,943. About 3.8% of families and 4.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 3.9% of those under age 18 and 9.0% of those age 65 or over.[65]

Government and politics

editLake Stevens is a non-charter code city with a mayor–council system of government.[66] The city council serves as the legislative body of the city government and has seven members who are elected at-large to four-year terms in staggered elections.[67][68]: 34 The council holds regular meetings twice a month at the Lake Stevens School District administrative headquarters and a work session during other weeks as needed.[69][70] The mayor is a full-time position that is also elected by Lake Stevens residents and serves as the executive of the city government during a four-year term.[71] Former city councilmember Brett Gailey, who was also employed by the Everett Police Department, was elected as mayor in 2019.[72][73]

The city government has budgeted expenditures of $50.4 million and revenues of $43.4 million in 2020, largely funded by sales, property, and utility taxes.[68] It has 85 employees organized into departments of economic development, finance, human resources, parks and recreation, planning, policing, and public works.[67][68]: 23 Lake Stevens has several non-elected executive positions, including the city administrator, city clerk, police chief, planning director, public works director, and community programs planner.[70] Several regional agencies provide other services, such as fire protection, library access, and water management.[70]

In addition to elected and executive positions, Lake Stevens has seven boards and commissions that advise the city council on a variety of specific issues. They are composed of volunteer citizens who are appointed to set terms by the mayor with the approval of the city council.[74][75] The boards and commissions are tasked with managing arts, civil service and police, the public library, parks and recreation, planning, city salaries, and veterans' rights.[70][76]

At the federal level, Lake Stevens is part of the 1st congressional district, which is represented by Democrat Suzan DelBene and stretches from Arlington to Bellevue.[77][78] The city was part of the 2nd congressional district until a redistricting in 2012 that split most of Northwestern Washington.[79][80] At the state level, Lake Stevens shares the 39th legislative district with Darrington, Granite Falls, and eastern Skagit County.[81] It was part of the 44th legislative district until 2022.[82] The city lies in the Snohomish County Council's 5th district, which also includes Snohomish and the Skykomish Valley.[83]

Culture

editThe city's annual summer festival, Aquafest, is held at North Cove Park in downtown Lake Stevens over a three-day weekend in late July. It was founded in 1960 and includes a boat parade, carnival rides, a car show, and a circus. The 2018 festival was attended by 30,000 people.[84] An annual Ironman 70.3 triathlon was added to Aquafest in the 2000s and features a 70.3-mile (113.1 km) course with swimming, cycling, and running segments.[85] The triathlon also serves as a qualifier for the Ironman World Championship.[86][87]

Parks and recreation

editLake Stevens has 195 acres (79 ha) of parks and open space managed by the city government, Snohomish County, and the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife.[88] The city government owns 158 acres (64 ha) and has nine parks that are categorized as community parks, neighborhood parks, mini-parks, and other facilities.[89] In addition to public facilities, the Lake Stevens area has 139 acres (56 ha) of private parks and open spaces that are owned by homeowner associations and other entities.[89]

The largest city-owned park is Eagle Ridge Community Park, located on 28 acres (11 ha) near the northwest shore of the lake, but largely undeveloped.[90] The county government owns three community parks in the Lake Stevens area. Cavalero Community Park opened in 2009 and consists of two fenced dog parks, an open field, and a planned skate park on 32 acres (13 ha).[91] Lake Stevens Community Park is located east of downtown and includes several soccer and baseball fields on 43 acres (17 ha) of former timber land.[89]: 7–8 [92] Davies Beach (formerly Willard Wyatt Park) lies at the foot of Chapel Hill on the western lakeshore and includes a beach, boat launch, and a boathouse for rowing teams.[93][94]

Several city parks are located along the shore of Lake Stevens, providing beaches with swimming areas and fishing docks.[89]: 11–14 Lundeen Park is the largest of the city's beaches and was developed out of a former resort that opened in 1908.[8] It also offers paddleboard and kayak rentals, a visitors center, and a concession stand.[95] At the northeast end of the lake is North Cove Park, a downtown park that is planned to be developed into an urban gathering space.[31] A disc golf course was opened in 2000 at Catherine Creek Park, a small park with hiking trails and natural areas.[85][89]: 10

The county government also owns Centennial Trail, an inter-city hiking, bicycling, and equestrian rail trail. It travels 30 miles (48 km) between Arlington and Snohomish, passing through the east side of Lake Stevens.[96] The city has several short trails that are owned by the Lake Stevens School District and private housing subdivisions, along with informal trails along a transmission line corridor.[89]: 19 Lake Stevens plans to develop and connect these routes into a full network, including the Bayview Trail on the transmission line in collaboration with the City of Marysville.[97][98] The city government also manages a community center near the city hall and library. Several local rowing clubs use Lake Stevens, including the in-city Lake Stevens Rowing Club that was founded in 1997.[89]: 21–24 [99]

Historical preservation

editThe local historical society operated a museum adjacent to the city library that opened in 1989 and included exhibits with fixtures from historic buildings and a collection of documents and photographs.[15] The museum grounds also included the Grimm House, a historic house that is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The house was constructed in 1903 for a mill worker and moved to the museum grounds in 1996, later undergoing extensive renovations before opening for public tours in 2004.[100] The museum was closed and demolished in June 2017 as part of the North Cove Park redevelopment, which also included moving the Grimm House to a new location adjacent to a future museum site.[101][102]

Notable people

edit- Travis Bracht, singer[103]

- Jacob Eason, professional American football player[104]

- Cory Kennedy, professional skateboarder[105]

- Kathryn Holloway, Paralympic volleyball player[106]

- Chris Pratt, actor[107]

- Karla Wilson, politician[108]

Education

editThe Lake Stevens School District operates a system of public schools within the city and surrounding areas, including a portion of southeastern Marysville.[109] The school district had an enrollment of approximately 8,838 students in 2016, with 436 total teachers and 239 other staff.[110] It has one high school, Lake Stevens High School, which opened at its current campus in 1979 and was approved for renovation work in 2016.[111] The renovation cost $116 million and began construction in June 2018, opening its first phase in November 2019.[112][113] The school district also has one mid-high school for grades 8–9, two middle schools, and seven elementary schools. The newest elementary school, Stevens Creek, opened in 2018 alongside an adjacent early learning center.[114]

The city's nearest post-secondary educational institutions are Everett Community College and Edmonds College.[115] During the late 2000s, Lake Stevens was a leading candidate for a proposed branch campus of the University of Washington (UW). The city government presented a 98-acre (40 ha) site on the southwest side of Cavalero Hill that was among the four finalists in 2007, but attracted controversy from neighbors for using land promised for a county park.[116][117] The Lake Stevens proposal scored the lowest in a survey of the finalists and the project was abandoned entirely in 2008 due to a state budget shortfall.[118][119]

Library

editThe first public library in Lake Stevens opened in 1946 at the home of a local resident and moved into a former post office three years later.[120] The city government moved the library to a former pharmacy in 1985 and contracted with Sno-Isle Libraries, an inter-county system that later annexed Lake Stevens in 2008.[28][121] The 2,400-square-foot (220 m2) downtown library building was the smallest in the Sno-Isle system and was determined to be unable to support the community's needs, necessitating plans for a replacement in the 2010s.[28]

Sno-Isle proposed a larger library with 20,000 square feet (1,900 m2) of space as part of a civic campus on Chapel Hill near Frontier Village, which would cost $17 million and be financed by a bond issue paid through property taxes.[33][122] The bond was approved by voters in the February 2017 election, but fell 749 votes short of meeting the turnout requirement to pass.[61] A second attempt in February 2018 was also rejected after failing to meet the 60 percent threshold for bonds.[123]

The library was demolished in June 2021 as part of renovations to North Cove Park and was replaced with a temporary library at Lundeen Park.[102][124] Sno-Isle moved into a former police station in August after it was renovated into a new facility with fewer amenities.[125][126] In January 2022, the city government proposed leaving the Sno-Isle system and using levy funds for the proposed civic campus as well as a privatized library system.[127] A few days later, the proposal was withdrawn and Sno-Isle announced that it would continue to pursue plans for a permanent library building with $3.1 million in state grants.[128] Site clearing at a site on Chapel Hill for the new library began in March 2023;[129] the two-story library building, which will incorporate mass timber construction and include 15,000 square feet (1,400 m2) of space, is scheduled to begin construction in 2025.[130]

Infrastructure

editTransportation

editLake Stevens is traversed by three state highways that connect the area to other parts of Snohomish County: State Route 9, running north–south through the west of the city and continuing to Snohomish and Arlington;[37] State Route 92, which continues northeast to Granite Falls; and State Route 204, which connects Frontier Village to U.S. Route 2 (US 2).[39][131] The intersection of State Route 9 and State Route 204 and several roads around Frontier Village were replaced by a series of four roundabouts in 2023 after a proposed interchange was scrapped.[132][133] The Hewitt Avenue Trestle, which carries US 2 to Everett, is a four-lane freeway that is frequently congested and is planned to be rebuilt to fix capacity issues.[134]

The city is also served by Community Transit, which operates bus routes between cities in Snohomish County. The agency provides all-day bus service from Lake Stevens to Everett, Granite Falls, Lynnwood, Marysville, and Snohomish.[135] The city has a small park and ride that opened in 2004 and is served by local routes as well as an express route to Lynnwood City Center station during peak hours on weekdays.[136][137]

Utilities

editThe city's electric power and tap water are provided by the Snohomish County Public Utility District (PUD), a consumer-owned public utility that serves all of Snohomish County.[138] The PUD sources its water from the City of Everett system at Spada Lake and Lake Chaplain, which is delivered to Lake Stevens and Granite Falls.[139] The city is also bisected by a pair of north–south electrical transmission lines operated by the Bonneville Power Administration that travel towards British Columbia.[140] Natural gas for Lake Stevens residents and businesses is provided by Puget Sound Energy.[141]

The city government contracts with Republic Services and Waste Management to provide curbside collection and disposal of garbage, recycling, and yard waste for different areas of Lake Stevens.[142] The Lake Stevens Sewer District, established in 1957, operates the city's sewer system and is planned to merge with the city government in 2032.[143] The sewer district built a treatment plant in 2013 at a cost of $100 million, and the debt payments on the project have caused disputes with the city.[144]

Healthcare

editLake Stevens has two urgent care centers that also provide medical services: a branch of The Everett Clinic (part of UnitedHealth Optum); and a 4,000-square-foot (370 m2) MultiCare Indigo Urgent Care Clinic that opened in 2017.[145][146]

References

edit- ^ a b "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 20, 2024.

- ^ "QuickFacts: Lake Stevens city, Washington". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 20, 2024.

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places in Washington: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2022". United States Census Bureau. May 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2024.

- ^ "Lake Stevens". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. September 10, 1979. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ Phillips, James W. (1971). Washington State Place Names. University of Washington Press. p. 138. ISBN 0-295-95158-3. OCLC 1052713900. Retrieved November 18, 2019 – via The Internet Archive.

- ^ Hollenbeck, Jan L.; Moss, Madonna (1987). A Cultural Resource Overview: Prehistory, Ethnography and History: Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest. United States Forest Service. p. 167. OCLC 892024380. Retrieved April 30, 2020 – via HathiTrust.

- ^ Twekesbury, Don (May 15, 1989). "Lake Stevens tackles ambitious birthday projects". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. p. B1.

- ^ a b c d e f Blake, Warner (December 8, 2017). "Lake Stevens — Thumbnail History". HistoryLink. Retrieved February 14, 2019.

- ^ Whitfield, William M. (1926). History of Snohomish County, Washington. Chicago: Pioneer Historical Publishing Company. pp. 614, 617. OCLC 8437390. Retrieved April 30, 2020 – via HathiTrust.

- ^ Hastie, Thomas P.; Batey, David; Sisson, E.A.; Graham, Albert L., eds. (1906). "Chapter VI: Cities and Towns". An Illustrated History of Skagit and Snohomish Counties. Chicago: Interstate Publishing Company. p. 372. LCCN 06030900. OCLC 11299996. Retrieved May 13, 2020 – via The Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c Schubert, Ruth (September 5, 1998). "Struggling to hold on to the small-town feel". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. p. D1.

- ^ a b Whitfield (1926), pp. 616–617.

- ^ a b "Looking back: Lake Stevens votes to become a city". The Everett Herald. November 23, 2019. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ^ Barrios, Joseph (July 24, 1995). "Lake Stevens' locomotive legend a reality". The Seattle Times. p. B1. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- ^ a b Whitely, Peyton (August 20, 2003). "Museum collection keeps close track of small city's history". The Seattle Times. p. H3. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- ^ Cameron, David A.; LeWarne, Charles P.; May, M. Allan; O'Donnell, Jack C.; O'Donnell, Lawrence E. (2005). Snohomish County: An Illustrated History. Index, Washington: Kelcema Books LLC. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-9766700-0-1. OCLC 62728798.

- ^ Whitely, Peyton (September 15, 2004). "Book recalls time before downtown was "ghost town"". The Seattle Times. p. H16. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- ^ Cameron et al. (2005), p. 253.

- ^ a b Blake, Warner (December 8, 2017). "Town of Lake Stevens incorporates on November 21, 1960". HistoryLink. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ a b Shoudy, Ad (July 24, 1985). "City celebrates first twenty-five years". Lake Stevens Journal. pp. 8–9. Archived from the original on March 30, 2022. Retrieved May 14, 2020 – via Lake Stevens Historical Museum.

- ^ Whitely, Peyton (July 14, 2004). "Lake aerator ready, but isn't needed yet". The Seattle Times. p. H26. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- ^ Siderius, Christina (March 25, 2007). "Lake Stevens: City looks big but feels like a small town". The Seattle Times. p. E5. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ a b Snohomish County Natural Hazard Mitigation Plan Update, Volume 2: Planning Partner Annexes (Report). Snohomish County. September 2015. p. 8-2. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- ^ Underwood, Doug (April 5, 1981). "SORE point: Hewlett-Packard rezoning faces challenge". The She Seattle Times. p. D5.

- ^ Bergsman, Jerry (February 6, 1985). "Hewlett-Packard begins move to new home". The Seattle Times. p. H1.

- ^ Logg, Cathy (December 2, 2005). "Lake Stevens attempts maximum annexations". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ Holtz, Jackson (December 22, 2006). "City takes over control of lake". The Everett Herald.

- ^ a b c Bray, Kari (August 15, 2014). "Rapid expansion has caused growing pains for Lake Stevens". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ a b Sheets, Bill (December 29, 2009). "Lake Stevens to add more than 10,000 through annexation". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ a b Bray, Kari (October 21, 2016). "Annexations would add thousands of people to Lake Stevens". The Everett Herald. Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- ^ a b c Bray, Kari (July 14, 2018). "Plan paints picture of change for downtown Lake Stevens". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ Bray, Kari (December 5, 2016). "Demolition time: Lake Stevens readies for new City Hall". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ a b Bray, Kari (December 29, 2017). "Voters again will consider a Lake Stevens library bond". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ Davey, Stephanie (September 30, 2019). "Lake Stevens police may soon have a new station". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ Bray, Kari (May 12, 2015). "Plan for new Lake Stevens civic center resurfaces". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ Haun, Riley (November 25, 2022). "On site once planned for city hall, Lake Stevens OK's commercial rezone". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- ^ a b Lindblom, Mike (September 3, 2019). "Washington's unofficial freeway: Highway 9 in Lake Stevens strains under a suburban boom". The Seattle Times. p. A1. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ^ a b "Lake Stevens". Snohomish County Public Works. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ^ a b c City of Lake Stevens Address and Street Map (Map). City of Lake Stevens. November 2017. Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- ^ Davey, Stephanie (January 5, 2021). "Thousands of residents — and the lake — could join Lake Stevens". The Everett Herald. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ "Chapter 1: Introduction". City of Lake Stevens 2015–2035 Comprehensive Plan. City of Lake Stevens. September 2015. p. 2. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- ^ a b c "State of the Lakes Report: Lake Stevens". Snohomish County Public Works. March 2003. pp. 2–4. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ "Lake Stevens At A Glance". City of Lake Stevens. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- ^ "Lake Stevens Lake Water Quality Restoration History". Snohomish County Public Works. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ Goffredo, Theresa (June 2, 2001). "A downtown is taking shape in Lake Stevens". The Everett Herald. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

- ^ a b Fetters, Eric (June 27, 2004). "Expanding Frontier". The Everett Herald Business Journal. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

- ^ "Chapter 2: Land Use". City of Lake Stevens 2015–2035 Comprehensive Plan. City of Lake Stevens. September 2015. pp. 10–11. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ a b "Selected Economic Characteristics: Lake Stevens, Washington". American Community Survey. United States Census Bureau. 2019. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ "Lake Stevens Economic Assessment". City of Lake Stevens. January 7, 2011. pp. 22–24. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ a b "Work Destination Report — Where Workers are Employed Who Live in the Selection Area — by Places (Cities, CDPs, etc.)". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 8, 2020 – via OnTheMap.

- ^ "Profile: Lake Stevens, Washington". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ a b "2012 Covered Employment Estimates". Puget Sound Regional Council. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ "Profile: Lake Stevens, Washington". Economic Alliance Snohomish County. Retrieved May 8, 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Catchpole, Dan (May 4, 2017). "Aerospace suppliers spending huge sums to boost capacity". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ "Agilent to close Lake Stevens campus, lay off 40". The Everett Herald Business Journal. September 2002. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- ^ Corliss, Bryan (December 18, 2001). "Solectron plant to close". The Everett Herald. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- ^ Fetters, Eric (October 17, 2003). "Former Agilent site to be redeveloped". The Everett Herald. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- ^ Haun, Riley (December 4, 2022). "The wait is over as Costco opens in Lake Stevens". The Everett Herald. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- ^ Davey, Stephanie (December 11, 2019). "Lake Stevens City Council approves Costco agreement". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ "Decennial Census of Population and Housing". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 26, 2013.

- ^ a b Bray, Kari (March 1, 2017). "After election, Lake Stevens Library awaits next chapter". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ Haglund, Noah; Bray, Kari (May 28, 2017). "Explosive growth encircles once-idyllic Lake Stevens". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ Davey, Stephanie (November 1, 2019). "City Council members face off in Lake Stevens mayoral race". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c "QuickFacts: Lake Stevens, Washington". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: Lake Stevens city, Washington" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 2000. Retrieved May 14, 2020 – via Puget Sound Regional Council.

- ^ "Chapter 2.04: Noncharter Code City". Lake Stevens Municipal Code. City of Lake Stevens. Retrieved April 30, 2020 – via Code Publishing Company.

- ^ a b "Accountability Audit Report: City of Lake Stevens (2017)". Washington State Auditor. February 4, 2019. p. 6. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ^ a b c "City of Lake Stevens 2020 Adopted Budget". City of Lake Stevens. November 1, 2019. p. 13. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- ^ "City Council". City of Lake Stevens. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Lake Stevens City Government". City of Lake Stevens. Archived from the original on February 14, 2008. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ^ Cornfield, Jerry (October 20, 2021). "Lake Stevens' first full-time mayor will make $80,000 a year". The Everett Herald. Retrieved March 12, 2021.

- ^ Haglund, Noah (November 6, 2019). "Edmonds, Lake Stevens and Sultan usher in changes at the top". The Everett Herald. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- ^ Bryan, Zachariah (May 4, 2020). "Everett settles cop's discrimination lawsuit for $549,000". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ^ Bray, Kari (September 3, 2014). "Lake Stevens sets up city salary commission". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ Bray, Kari (May 7, 2017). "Lake Stevens forms group to focus on rights, needs of veterans". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ "Title 2: Administration and Personnel" (PDF). Lake Stevens Municipal Code. City of Lake Stevens. February 2020. pp. 35–47. Retrieved May 5, 2020 – via Code Publishing Company.

- ^ Cornfield, Jerry (October 24, 2022). "Incumbents DelBene, Larsen say country is heading in right direction". The Everett Herald. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Census Bureau Geography Division (2023). 118th Congress of the United States: Washington – Congressional District 1 (PDF) (Map). 1:118,000. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Cornfield, Jerry (January 3, 2012). "Stymied by redistricting, Liias scraps run for Congress". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ Cornfield, Jerry (July 28, 2018). "DelBene faces four challengers looking to change dynamic in DC". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ Washington State Redistricting Commission (July 15, 2022). "Legislative District 39" (PDF) (Map). District Maps Booklet 2022. Washington State Legislative Information Center. p. 40. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Cornfield, Jerry (December 3, 2021). "State Supreme Court declines to draw new redistricting plan". The Everett Herald. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Snohomish County: County Council Districts (Map). Snohomish County Elections. May 12, 2022. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Brown, Andrea (July 27, 2019). "Aquafest is three-day party on the Lake Stevens waterfront". The Everett Herald. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ^ a b Fiege, Gale (August 15, 2014). "Lake is just the jumping off point for fun in Lake Stevens". The Everett Herald. Retrieved March 25, 2019.

- ^ "Aussies duel at Lake Stevens Ironman triathlon". The Everett Herald. July 7, 2008. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- ^ Cane, Mike (July 21, 2006). "Committed to the triathlon challenge". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- ^ Mattingly-Arthur, Megan (February 10, 2016). "Natural beauty of Lake Stevens". The Everett Herald. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Chapter 5: Parks, Recreation and Open Space Element". City of Lake Stevens 2015–2035 Comprehensive Plan. City of Lake Stevens. September 2015. pp. 4–5. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ^ "Eagle Ridge Park". City of Lake Stevens. April 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Bray, Kari (December 9, 2016). "'Worth the wait': Lake Stevens skate park could open by August". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ^ "Lake Stevens Community Park". City of Lake Stevens. April 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Banel, Feliks (February 21, 2020). "All Over The Map: Family responds to name being removed from Lake Stevens park". MyNorthwest.com. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ^ Sanders, Julia-Grace (May 2, 2019). "New Lake Stevens boathouse honors one of the 'Boys' of 1936". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ^ Bray, Kari (June 28, 2016). "Changes at Lake Stevens park include paddlesport rentals". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ^ Fiege, Gale (August 9, 2013). "People traveling Centennial Trail, end to end, for 1st time". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ^ Watanabe, Ben (February 14, 2022). "Transportation package could bring $600M to Snohomish County". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- ^ Watanabe, Ben (April 30, 2023). "Lake Stevens, Marysville seek Bayview Trail design input". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- ^ Bray, Kari (January 19, 2017). "Lake Stevens Rowing Club brings together people of all ages". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ^ Thompson, Evan (October 6, 2019). "This Lake Stevens house is a relic of a time long gone". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- ^ Bray, Kari (February 9, 2018). "Vote on Tuesday could be crucial for Lake Stevens project". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- ^ a b Breda, Isabella (June 26, 2021). "History will live on in a transformed Lake Stevens downtown". The Everett Herald. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ O'Donnell, Jack (July 30, 2014). "Seems Like Yesterday". The Everett Herald. Retrieved June 6, 2020.

- ^ Vorel, Mike (April 25, 2020). "After falling to Indianapolis Colts in fourth round of NFL draft, former UW QB Jacob Eason vows to prove critics wrong". The Seattle Times. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- ^ Clarridge, Christine; Lacitis, Erik (September 1, 2017). "Local pro skateboarder Cory Kennedy arrested after Vashon Island crash kills beloved videographer". The Seattle Times. Retrieved February 13, 2019.

- ^ "Katie Holloway". Team USA. United States Olympic Committee. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved March 12, 2021.

- ^ Bray, Kari (September 25, 2014). "Chris Pratt's star rises, but Lake Stevens roots keep him grounded". The Everett Herald. Retrieved February 13, 2019.

- ^ Brown, Andrea (January 31, 2023). "Former state Rep. Karla Wilson, 88, remembered as 'smart, energetic'". The Everett Herald. Retrieved February 2, 2023.

- ^ Snohomish County School Districts Map (PDF) (Map). Snohomish County. December 21, 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 23, 2020. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

- ^ "Public School District Directory Information: Lake Stevens School District". National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

- ^ Frey, Lorna (September 26, 1979). "What high school students are saying about life at the new Viking High". Lake Stevens Journal. p. 1. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved April 28, 2020 – via Lake Stevens Historical Museum.

- ^ Davey, Stephanie (February 29, 2020). "Lake Stevens now has a Snapchat-worthy high school". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ Davey, Stephanie (March 22, 2019). "Lake Stevens High School remodeling delayed and over budget". The Everett Herald. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

- ^ Bray, Kari (March 5, 2017). "Opening day for new Lake Stevens elementary delayed a year". The Everett Herald. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

- ^ "College Navigator: ZIP Code 98258". National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ Thompson, Lynn (November 7, 2007). "Each of 4 finalist sites has promise, problems". The Seattle Times. p. I14.

- ^ Cornfield, Jerry (November 5, 2007). "Lake Stevens UW site loses ground". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- ^ Cornfield, Jerry (January 24, 2008). "Lake Stevens officials make case for UW campus". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- ^ Long, Katherine (May 23, 2011). "Steps taken toward creating WSU branch campus in Everett". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- ^ Parker, Jackie (April 6, 2021). "Lake Stevens Library Through History". Sno-Isle Libraries. Retrieved December 23, 2023.

- ^ Stevick, Eric (June 6, 2008). "Lake Stevens Library reopens after flood". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ Bray, Kari (October 31, 2016). "Two measures for new Lake Stevens library on Feb. 14 ballot". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ Bray, Kari (February 18, 2018). "Bond for new Lake Stevens library falling short of required votes". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ "Sno-Isle Libraries prepares for heat with libraries as 'cooling centers'". North County Outlook. June 25, 2021. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ "Lake Stevens Library opens doors to its latest home". Sno-Isle Libraries. August 30, 2021. Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- ^ "Temporary Lake Stevens Library to open this summer". The Everett Herald. July 30, 2021. Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- ^ Breda, Isabella (January 22, 2022). "Lake Stevens proposes cutting ties with Sno-Isle Libraries". The Everett Herald. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- ^ Breda, Isabella (January 25, 2022). "Lake Stevens ditches plan to cut ties with Sno-Isle Libraries". The Everett Herald. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ Gates, Sophia (March 24, 2023). "Site clearing begins for new Lake Stevens library". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- ^ Hinchliffe, Emma (February 12, 2024). "Mass timber library set for Lake Stevens". Seattle Daily Journal of Commerce. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- ^ Washington State Department of Transportation (2014). Washington State Highways, 2014–2015 (PDF) (Map). 1:842,000. Olympia: Washington State Department of Transportation. Puget Sound inset. Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- ^ Hansen, Jordan (September 2, 2023). "Blessing or baffling? Lake Stevens' new roundabout maze divides drivers". The Everett Herald. Retrieved September 3, 2023.

- ^ Giordano, Lizz (February 25, 2019). "Maybe 4 roundabouts can fix this nightmare intersection". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ Cornfield, Jerry (March 3, 2018). "Taming the traffic-troubled U.S. 2 trestle". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ Haglund, Noah (August 27, 2016). "Community Transit's new bus routes to serve Highway 9 corridor". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ Schwarzen, Christopher (December 15, 2004). "New way to downtown Seattle". The Seattle Times. p. H15. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ "New bus routes for Seattle commuters". Community Transit. July 22, 2024. Retrieved November 8, 2024.

- ^ "Quick Facts for Snohomish County PUD" (PDF). Snohomish County Public Utility District. October 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 29, 2018. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- ^ Malakoff, Morris (February 25, 2008). "Dry season no threat to local H2O supply". The Enterprise. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- ^ BPA Transmission Lines and Facilities (PDF) (Map). Bonneville Power Administration. February 2, 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 28, 2017. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ "PSE locations". Puget Sound Energy. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ "Public Utilities". City of Lake Stevens. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ Bray, Kari (July 23, 2017). "City of Lake Stevens, sewer district plan to merge". The Everett Herald. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- ^ Haglund, Noah; Davey, Stephanie (September 18, 2019). "Sewer dispute spills into public in Lake Stevens". The Everett Herald. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- ^ Salyer, Sharon (February 29, 2016). "DaVita HealthCare Partners completes Everett Clinic purchase". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ Davis, Jim (July 28, 2017). "Everett Clinic, two others open new health-care clinics". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 8, 2020.