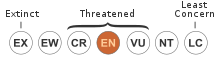

The gray woolly monkey (Lagothrix lagothricha cana) or Geoffroy's woolly monkey is a subspecies of the common woolly monkey from South America. It is found in Bolivia, Brazil and Peru. L. l. cana gets its common name, gray woolly monkey, from its thick gray coat. Its hands, feet, face and the inside of the arms are dark in color.[3] The gray woolly monkey has been considered endangered by IUCN since 2008. The subspecies is listed as endangered because it suffered a 50% decrease in population over the past 45 years due to deforestation and hunting.[2]

| Gray woolly monkey[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Near the Tarumã Açu River, Brazil | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Atelidae |

| Genus: | Lagothrix |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | L. l. cana

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Lagothrix lagothricha cana (É. Geoffroy, 1812)

| |

| |

| Geographic range (includes L. l. tschudii) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Lagothrix cana | |

Taxonomy

editInitially thought to be a subspecies of the common woolly monkey (L. lagothricha), it was later reclassified as its own species. Two subspecies of Lagothrix cana were known: L. c. cana and L. c. tschudii. L. c. cana in both Brazil and Peru and L. c. tschudii in southeastern Peru and in the Madidi National Park in Bolivia. However, a 2014 study supported reclassifying it again within L. lagothrica, with both subspecies being different subspecies of L. lagothrica.[2][4][5][6]

Habitat

editThe gray woolly monkey predominantly lives in cloud forest, a type of forest under cloud cover for most of the year. They can be found anywhere from 1,000 to 2,500 metres above sea level. The population of gray woolly monkeys in Bolivia have been reported to be found as low as 700 metres above sea level.[4] They spend the majority of their time high in the tree tops in search of food.[7] They move through the trees using their large prehensile tails, which is a common trait seen in the family Atelidae.[8] They are capable of hanging from their tails and often use them to bridge gaps between trees when travelling in them.[9]

Diet

editThe gray woolly monkey predominantly eats fruit, but occasionally when fruit is scarce will eat young leaves and sometimes seeds.[7]

Groups

editGray woolly monkeys live in groups of 11 to 25 members. These groups are of both mixed ages and sexes.[8] The group will move together and show little aggression towards other groups, and will often share the best feeding spots with other groups.[3]

Size

editIn general, males are larger than females. A male's head-body length ranges from 46 to 65 cm in length. A female's head-body length ranges from 46 to 58 cm in length. The tail length of the gray woolly monkey is on average from 66 to 68 cm in length.[3] The male gray woolly monkey weighs an average of 9.5 kg. The female gray woolly monkey weighs an average of 7.7 kg.[10]

Threats

editThe main threat the subspecies faces is hunting. They are hunted for food and pets. The females are often targeted for hunting as they are shot and then their offspring are taken and sold as pets. One story from the western Amazon reported several hunters who killed over 200 woolly monkeys in less than two years, which led to their local extinction. Deforestation is another major threat. Mining for cassiterite, a mineral used to make tin, is also a threat for both losing habitat and hunting.[11]

Conservation

editThe gray woolly monkey is currently protected in many national parks.[2] They are also listed in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade of Endagenered Species (CITES).[12] The following is a list of protected areas in Brazil where the gray woolly monkey occurs or may occur.[2]

- Amazonia National Park

- Mapinguari National Park

- Abufari Biological Reserve

- Jaru Biological Reserve

- Iquê Ecological Station

- Rio Acre Ecological Station

- Cuniã Ecological Station

- Jatuarana National Forest

- Macauá National Forest

- São Francisco National Forest

- Santa Rosa do Purus National Forest

- Humaita National Forest

- Jamari National Forest

- Bom Futuro National Forest

- Purus National Forest

- Mapiá-Inauini National Forest

- Pau Rosa National Forest

- Tefe National Forest

The entire known population of these monkeys in Bolivia are found in the Apolobamba Natural Area of Integrated Management and the Madidi National Park and Natural Area of Integrated Management.[2]

References

edit- ^ Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 151–152. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b c d e f Cornejo, F.M.; Stevenson, P.R.; Wallace, R.B.; Ravetta, A.L.; Valença-Montenegro, M.M.; Rylands, A.B. & Messias, M.R. (2021). "Lagothrix lagothricha ssp. cana". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T39962A192308612. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-1.RLTS.T39962A192308612.en.

- ^ a b c Rowe, N. (1996) The Pictorial Guide to the Living Primates. Pogonias Press, Rhode Island. ISBN 0964882515.

- ^ a b Wallace, R.B.; Painter, R.L.E. (1999). "A new primate record for Bolivia: an apparently isolated population of common woolly monkeys representing a southern range extension for the genus Lagothrix" (PDF). Neotropical Primates. 7 (4): 111–112.

- ^ "ITIS - Report: Lagothrix lagothricha". www.itis.gov. Retrieved 2021-11-20.

- ^ Messias, Mariluce Rezende; Valença-Montenegro, Mônica Mafra; Stevenson, Pablo R.; Ravetta, André Luis; Groups), Robert B. Wallace (IUCN SSC Specialist Group member-several; Fanny M. Cornejo (Dept. of Anthropology, Stony Brook University); International), Anthony B. Rylands (Conservation (2020-03-16). "IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Lagothrix lagothricha ssp. cana". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- ^ a b Peres, C. A. (1994). "Diet and feeding ecology of gray woolly monkeys (lagothrix lagotricha cana) in Central Amazonia: Comparisons with other Atelines". International Journal of Primatology. 15 (3): 333–372. doi:10.1007/BF02696098. S2CID 42459327.

- ^ a b Di Fiore, A. and Campbell, C.J. (2007) The atelines: variation in ecology, behavior, and social organization. In: Campbell, C.J., Fuentes, A., MacKinnon, K.C., Panger, M. and Bearder, S.K. (Eds.) Primates in Perspective. Oxford University Press, New York. ISBN 0195171349.

- ^ Rosenberger, A.L.; Strier, K.B. (1989). "Adaptive radiation of the ateline primates". Journal of Human Evolution. 18 (7): 717–750. doi:10.1016/0047-2484(89)90102-4.

- ^ Ford, S. M.; Davis, L. C. (1992). "Systematics and body size: Implications for feeding adaptations in new world monkeys". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 88 (4): 415–68. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330880403. PMID 1503118.

- ^ Peres, C.A. (1990). "Effects of hunting on western Amazonian primate communities". Biological Conservation. 54 (1): 47–59. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(90)90041-m.

- ^ CITES (December, 2011) http://www.cites.org/