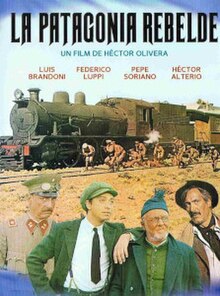

Rebellion in Patagonia (Spanish: La Patagonia rebelde) is a 1974 Argentine drama-historical film directed by Héctor Olivera and starring Héctor Alterio, Luis Brandoni, José Soriano and Federico Luppi. It was written by Olivera with Osvaldo Bayer and Fernando Ayala, based on Osvaldo Bayer's renowned novel Los vengadores de la Patagonia Trágica ("The Avengers of Tragic Patagonia"), which was based upon the military suppression of anarchist union movements in Santa Cruz Province in the early 1920s.

| Rebellion in Patagonia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Héctor Olivera |

| Screenplay by | Héctor Olivera Fernando Ayala Osvaldo Bayer |

| Based on | Los Vengadores de la Patagonia Trágica by Osvaldo Bayer |

| Produced by | Fernando Ayala |

| Starring | Héctor Alterio Luis Brandoni Federico Luppi José Soriano Fernando Iglesias 'Tacholas' |

| Cinematography | Victor Hugo Caula |

| Edited by | Oscar Montauti |

| Music by | Óscar Cardozo Ocampo |

| Distributed by | Tricontinental Film Center (United States) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 110 min. |

| Country | Argentina |

| Language | Spanish |

It was entered into the 24th Berlin International Film Festival, where it won the Silver Bear.[1]

It was selected as the second greatest Argentine film of all time in a poll conducted by the Museo del Cine Pablo Ducrós Hicken in 1984, while it ranked 3rd in the 2000 edition.[2] In a new version of the survey organized in 2022 by the specialized magazines La vida util, Taipei and La tierra quema, presented at the Mar del Plata International Film Festival, the film reached the 25 position.[3] Also in 2022, the film was included in Spanish magazine Fotogramas's list of the 20 best Argentine films of all time.[4]

Plot

editThe movie begins with the assassination of Lieutenant Coronel Zavala presumably for the events that take place during the movie, after he awakes from a nightmare full of gunshots.

Workers in Patagonia, influenced by anarcho-syndicalist ideas, demand improvements in hotel pay and conditions. During one of the meetings, a boss pays back the workers salaries and an additional fee. He takes the money out of his wallet which illustrates that to the boss it is simply pocket change where as to the workers it is a lot of money. After employers initially agree to workers' demands, which are supported by workers in other sectors and areas, the regional governor, under pressure from local employers, order the paramilitary police to intervene to suppress union and political activity, despite the protests of a local judge. In response to such harassment, a general strike is declared, paralyzing the ports and wool production for export. The national Radical Civic Union government supports the workers' rights, and the workers call for union recognition and improvements to the conditions of agricultural workers. Employers reject the demands and bring in replacement workers, but the convoys are attacked by armed strikers who shoot down the soldiers guarding them. Workers use arson and sabotage to disrupt production and take hostages. More fighting erupts between armed police and strikers.

An army- and judge-led mediation attempt commissioned by President Yrigoyen and led by Lieutenant Coronel Zavala condemns police partiality and the exploitative nature of the company store system. After six weeks, the strike is settled in the workers' favor with the first ever collective agreement for Patagonian rural workers and they hand in many of the weapons they seized from the rural estates as part of the agreement. Employers are outraged by having the unfavorable terms imposed on them by the government and respond with selective sackings and denial of service at company stores. Workers respond with boycotts and the president dismisses the governor, who is close to many of the wealthy landowners. More importantly, the landowners refuse to implement the pay rise specified in the agreement.

With workers planning another strike to enforce the terms of the agreement, employers, backed by Chile and Britain, successfully force the government to round up union leaders and militants. Another general strike is called in response. While strikers take hostages to defend themselves, bandits known as the Red Council who had previously taken part in the attack on the convoy of replacement workers and refused to disarm, take advantage of the unsettled situation to raid isolated estates.

Zavala is told of the continuing unrest despite his efforts, that he workers had not upheld their bargain by disarming, and to "Think of Chile" implying a threat to their borders, and is ordered to restore order in such a way as to permanently remove the threat of rebellion due to socialist or anarchist ideas, which they do by using acting in force, opening fire on strikers without warning, surprising the strikers who had held him in high regard for settling the earlier dispute in their favor. Following this initial fight and others using similar tactics Zavala begins carrying out summary executions, especially of the leaders and even of delegations acting under a flag of truce, some of whom are made to dig their own graves. Eventually the Red Council is captured in a villa they were raiding and the anarcho-syndicalists decide to surrender to Zavala. Armed landowners participate in the suppression of the strikers, identifying the leaders with most of the leaders of the movement being executed with only one managing to escape. Others are tied naked to fences or made to run the gauntlet.

After the slaughter, the previous agreement is annulled and wages are reduced. The film ends with oligarchs congratulating the lieutenant colonel in charge of the massacre during a celebration and singing For He's a Jolly Good Fellow in English.

Cast

edit- Pedro Aleandro - Félix Novas

- Héctor Alterio - Col. Zavala

- Luis Brandoni - Antonio Soto

- Franklin Caicedo - Farina 'El chileno'

- Horacio Dener - Obrero

- José María Gutiérrez - Gobernador Méndez Garzón

- Alfredo Iglesias - Ministro Gómez

- Fernando Iglesias 'Tacholas' - Graña 'El español'

- Maurice Jouvet - Don Federico

- Claudio Lucero - Comisario Micheri

- Federico Luppi - Jose Font, 'Facon Grande'

- Carlos Muñoz - Don Bernardo

- Eduardo Muñoz - Carballeira

- Héctor Pellegrini - Capitán Arzeno

- Jorge Rivera López - Edward Mathews

- Walter Santa Ana - Dueño del hotel

- José Soriano - Schultz, the German

- Osvaldo Terranova - Outerello

- Jorge Villalba - Florentino Cuello 'El gaucho'

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Berlinale 1974: Prize Winners". berlinale.de. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- ^ "Las 100 mejores del periodo 1933-1999 del Cine Argentino". La Mirada Cautiva (3). Buenos Aires: Museo del Cine Pablo Ducrós Hicken: 6–14. 2000. Archived from the original on 21 November 2022. Retrieved 21 November 2022 – via Encuesta de cine argentino 2022 on Google Drive.

- ^ "Top 100" (in Spanish). Encuesta de cine argentino 2022. 11 November 2022. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ Borrull, Mariona (17 July 2022). "Las 20 mejores películas argentinas de la historia". Fotogramas (in Spanish). Madrid: Hearst España. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

External links

edit