This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2016) |

The Louisville and Nashville Railroad (reporting mark LN), commonly called the L&N, was a Class I railroad that operated freight and passenger services in the southeast United States.

| |

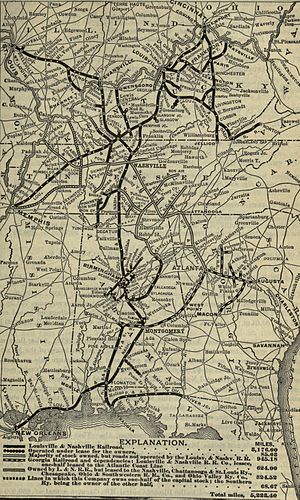

L&N system map, c. 1901 | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Louisville and Nashville Railroad Office Building, 908 West Broadway, Louisville, Kentucky (1907–1980) Seaboard Coast Line Railroad Building, 500 Water Street, Jacksonville, Florida (1980–1982) |

| Reporting mark | LN |

| Locale | Alabama Florida Georgia Illinois Indiana Kentucky Louisiana Mississippi Missouri Ohio Tennessee Virginia North Carolina |

| Dates of operation | 1850–1982 |

| Successor | Seaboard Coast Line Railroad |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Previous gauge | 5 ft (1,524 mm), converted by 1870.[1][2] |

| Length | 10,396 miles (16,731 kilometers) |

Chartered by the Commonwealth of Kentucky in 1850, the road grew into one of the great success stories of American business. Operating under one name continuously for 132 years, it survived civil war and economic depression and several waves of social and technological change. Under Milton H. Smith, president of the company for 30 years, the L&N grew from a road with less than three hundred miles (480 km) of track to a 6,000-mile (9,700 km) system serving fourteen states. As one of the premier Southern railroads, the L&N extended its reach far beyond its namesake cities, stretching to St. Louis, Memphis, Atlanta, and New Orleans. The railroad was economically strong throughout its lifetime, operating freight and passenger trains in a manner that earned it the nickname, "The Old Reliable".

Growth of the railroad continued until its purchase and the tumultuous rail consolidations of the 1980s which led to continual successors. By the end of 1970, L&N operated 6,063 miles (9,757 km) of road on 10,051 miles (16,176 km) of track, not including the Carrollton Railroad.

In 1971 the Seaboard Coast Line Railroad, successor to the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad, purchased the remainder of the L&N shares it did not already own, and the company became a subsidiary. By 1982, the Seaboard Coast Line had absorbed the Louisville & Nashville Railroad entirely. Then in 1986, the Seaboard System merged with the C&O and B&O (known as the Chessie System) and the combined company became CSX Transportation (CSX), which now owns and operates all of the former Louisville and Nashville lines.

Early history and Civil War

editIts first line extended barely south of Louisville, Kentucky, and it took until 1859 to span the 180-odd miles (290 km) to its second namesake city of Nashville. There were about 250 miles (400 km) of track in the system by the outbreak of the Civil War, and its strategic location, spanning the Union/Confederate lines, made it of great interest to both governments.

During the Civil War, different parts of the network were pressed into service by both armies at various times, and considerable damage from wear, battle, and sabotage occurred. (For example, during the Battle of Lebanon in July 1863, the company's depot in Lebanon, Kentucky, was used as a stronghold by outnumbered Union troops). However, the company benefited from being based in Kentucky, a southern border state that initially had competing Unionist and Confederate state governments, but with Bowling Green (the latter's capital) and Nashville falling to Union forces within the first year of the war, remaining in their hands for the war's duration. The company profited from Northern haulage contracts for troops and supplies, paid in sound Federal greenbacks, as opposed to the rapidly depreciating Confederate dollars. After the war, other railroads in the South were devastated to the point of collapse, and the general economic depression meant that labor and materials to repair its roads could be had fairly cheaply.

Buoyed by these fortunate circumstances, the firm began an expansion that never really stopped. Within 30 years the network reached from Ohio and Missouri to Louisiana and Florida. By 1884, the firm had such importance that it was included in the Dow Jones Transportation Average, the first American stock market index. It was such a large customer of the Rogers Locomotive and Machine Works, the country's second-largest locomotive maker, that in 1879 the firm presented L&N with a free locomotive as a thank-you bonus.

Beginning in 1858 and continuing throughout its history, the primary repair shops for rolling stock were located in Louisville, Kentucky. The first shops were acquired from the Kentucky Locomotive Works in 1858. However, this location could not be expanded, so a new tract of land was purchased in 1904 at the south side of the city. The new shops featured a central, 920-foot long transfer table that connected the main buildings. From that year until the 1920s, the South Louisville Shop built many of its own locomotives as well as repairing them. The shops in Decatur, Alabama were used to build most of the system's freight cars. The only other significant shops were located in Howell, Indiana, built in 1889.[citation needed]

Coal and capital in the Gilded Age

editSince all locomotives of the time were steam-powered, many railroads had favored coal as their engines' fuel source after wood-burning models were found unsatisfactory. The L&N guaranteed not only its own fuel sources but a steady revenue stream by pushing its lines into the difficult but coal-rich terrain of eastern Kentucky, and also well into northern Alabama. There the small town of Birmingham had recently been founded amidst undeveloped deposits of coal, iron ore and limestone, the basic ingredients of steel production. The arrival of L&N transport and investment capital helped create a great industrial city and the South's first postwar urban success story. The railroad's access to good coal enabled it to claim for a few years starting in 1940 the nation's longest unrefuelled run, about 490 miles (790 km) from Louisville to Montgomery, Alabama.

In the Gilded Age of the late 19th century there were no such things as anti-trust or fair-competition laws and very little financial regulation. Business was a keen and mean affair, and the L&N was a formidable competitor. It would exclude upstarts like the Tennessee Central Railway Company from critical infrastructure like urban stations. Where that wasn't possible, as with the Nashville, Chattanooga and St. Louis Railway (which was older than the L&N), it simply used its financial muscle—in 1880 it acquired a controlling interest in its chief competitor. A public outcry convinced the L&N directors that there were limits to their power. They discreetly continued the NC&StL as a separate subsidiary, but now working with, instead of in competition with, the L&N.

Ironically, in 1902 financial speculations by financier J.P. Morgan delivered control of the L&N to its rival Atlantic Coast Line Railroad, but that company did not attempt to control L&N operations, and for many decades there were no consequences of this change.

The L&N also attempted an expansion into foreign trade, through investments into the Export Coal Company, and the creation of a wholly owned subsidiary the "Gulf Transit Company" in 1895. This operated three ships, the SS Pensacola, the SS August Belmont, and the SS E. O. Saltmarsh. The venture ended with the sale of the Pensacola in 1906 and the selling off of the remaining assets in 1915.[3]

20th century

editThe World Wars placed heavy demand on the L&N. Its widespread and robust network coped well with the demands of war transport and production, and the resulting profits harked back to the boost it had received from the Civil War. In the postwar period, the line shifted gradually to diesel power, and the new streamlined engines pulled some of the most elegant passenger trains of the last great age of passenger rail, such as the Dixie Flyer, the Humming Bird, and the Pan-American.

Though well past its 100th anniversary, the line was still growing. The railroad retired its last steam locomotive, a J-4 class 2-8-2 Mikado #1882, from active service on January 28, 1957.[4] Also in that year, the Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis was finally fully merged. In the 1960s, acquisitions in Illinois allowed a long-sought entry into the premier railroad nexus of Chicago, and some of the battered remains of the old rival, the Tennessee Central, were sold to the L&N as well.

In 1971 the Seaboard Coast Line Railroad, successor to the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad, purchased the remainder of the L&N shares it did not already own, and the company became a subsidiary. Prior to the purchase, the L&N, like other railroads, had curtailed passenger service in response to dwindling ridership. Amtrak, the government-formed passenger railway service, took over the few remaining L&N passenger trains in 1971. In 1979, amid great lamentations in the press, the last passenger service over L&N rails ceased when Amtrak discontinued The Floridian, which had connected Louisville with Nashville and continued to Florida via Birmingham.

By 1982, as the railroad industry consolidated, the Seaboard Coast Line absorbed the Louisville & Nashville Railroad entirely. The merged company was known as "SCL/L&N", "Family Lines", and was depicted as such on the railroad's rolling stock. During the next few years several smaller acquisitions resulted in the creation of the Seaboard System Railroad. Yet more consolidation was ahead, and in 1986, the Seaboard System merged into the C&O/B&O combined system known as the Chessie System. The combined company became CSX Transportation (CSX), which now owns and operates all of the former Louisville and Nashville lines, except for some routes abandoned or sold off.

Legacy

editSeveral historical groups and publications devoted to the line exist, and L&N equipment is well represented in the model railroading hobby. The L&N Railroad is mentioned by country music pioneer Jimmie Rodgers in his "Blue Yodel #7". It is also the subject of the 2003 Rhonda Vincent bluegrass song "Kentucky Borderline", as well as "The L&N Don't Stop Here Anymore" by Jean Ritchie and individually performed by Michelle Shocked, Johnny Cash, Billy Bragg & Joe Henry, and Kathy Mattea. Dutch blues/rock band The Bintangs had a hit in the Dutch charts in the late 1960s with "Ridin' on the L&N" (a cover from the Dan Burley/Lionel Hampton composition from 1946). This composition also was covered by John Mayall & the Bluesbreakers. The L&N is also mentioned in the Lost Dog Street Band song “Last Train”, written by Benjamin Tod, from their 2024 album Survived.

In 1926 the L&N turned over approximately 137 acres[5] to the Kentucky State Park Commission, making possible the creation of the state's Natural Bridge State Park.

| L&N | NC&StL | LH&StL | Cumberland & Manchester | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1925 | 12506 | 1306 | 410 | 4 |

| 1933 | 6871 | 851 | (incl in L&N) | (into L&N) |

| 1944 | 17398 | 2766 | ||

| 1956 | 15257 | 2073 | ||

| 1960 | 16455 | (merged) | ||

| 1970 | 30580 | |||

| Totals do not include the Carrollton Railroad. | ||||

Passenger operations

editThe Humming Bird and Pan-American, both from Cincinnati to New Orleans and Memphis, were two of the L&N's most popular passenger trains that ran entirely on its own lines. However, the Humming Bird later added a Chicago to New Orleans section in conjunction with the Chicago & Eastern Illinois Railroad utilizing the Georgian north of Nashville. (The Official Guide of the Railroads, February 1952) The railroad also hosted other named trains, including:[citation needed]

- Azalean (Cincinnati – New Orleans) (had through Pullman Company Sleeping Cars between Cincinnati and New York over the Pennsylvania Railroad) ran combined with the Washington – Atlanta – New Orleans Express (New York – New Orleans in conjunction with the Pennsylvania Railroad, Southern Railway and the West Point Route); these trains combined south of Montgomery.

- Pre-Amtrak Crescent (New York – New Orleans in conjunction with the Pennsylvania Railroad, Southern Railway and the West Point Route)

- Dixie Flagler (Chicago – Miami in conjunction with the Chicago & Eastern Illinois Railroad, Nashville, Chattanooga and St. Louis Railway, Atlantic Coast Line Railroad and the Florida East Coast Railway)

- Dixie Flyer and Dixie Limited (Chicago and St. Louis to Jacksonville in conjunction with the Chicago & Eastern Illinois Railroad, Nashville, Chattanooga and St. Louis Railway, Central of Georgia Railway and the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad)

- Dixieland (Chicago – Miami in conjunction with the Chicago & Eastern Illinois Railroad, Nashville, Chattanooga and St. Louis Railway, Atlantic Coast Line Railroad and the Florida East Coast Railway)

- Dixiana (Chicago – Miami in conjunction with the Chicago & Eastern Illinois Railroad, Nashville, Chattanooga and St. Louis Railway, Atlantic Coast Line Railroad and the Florida East Coast Railway)

- Flamingo (Cincinnati – Jacksonville in conjunction with the Central of Georgia Railway, Atlantic Coast Line)

- Florida Arrow (seasonal train, Chicago – Louisville – Birmingham – Miami in conjunction with the Pennsylvania Railroad, Atlantic Coast Line Railroad and the Florida East Coast Railway)

- Georgian (Originally St. Louis – Atlanta, later changed to Chicago-Atlanta in conjunction with the Chicago & Eastern Illinois Railroad and the Nashville, Chattanooga and St. Louis Railway)

- Gulf Wind (New Orleans – Jacksonville in conjunction with the Seaboard Air Line Railroad)

- Piedmont Limited (New York – New Orleans in conjunction with the Pennsylvania Railroad, Southern Railway and the West Point Route)

- Southland (Chicago – St. Petersburg, Tampa and Miami in conjunction with the Pennsylvania Railroad, Central of Georgia Railway and the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad. The Wabash Railroad had a connection in Fort Wayne, for trips from Detroit.)

- South Wind (Chicago – Miami in conjunction with the Pennsylvania Railroad, Atlantic Coast Line Railroad and the Florida East Coast Railway)

The L&N was one of few railroads to discontinue a passenger train that was en route. On January 9, 1969, as soon as a judge lifted the injunction preventing its discontinuance, the L&N discontinued its southbound Humming Bird at Birmingham, in mid-run from Cincinnati to New Orleans. The 14 passengers continuing south did so by bus.[6]

Preservation

editThere are several preservation organizations of L&N equipment and L&N lines, such as the Kentucky Railway Museum, The Historic Railpark and Train Museum in Bowling Green, Kentucky, and the L&N Historical Society.

The city of Atlanta, Georgia, is home to the General and the Texas, two 4-4-0 locomotives originally built for the Western and Atlantic Railroad, which was later leased to L&N predecessor Nashville, Chattanooga, and St. Louis. The lease of the W&A was passed to, and renewed by, L&N and its successors. The General and the Texas became famous for being participants in The Great Locomotive Chase during the Civil War. The General had been placed on display in the railroad's Union Depot in Chattanooga in 1901. In 1957, the L&N removed the engine and restored it to operating condition. The engine pulled the railroad's wooden center-door Jim Crow combine coach No. 665 as it traveled throughout the eastern U.S. as part of the observance of the Civil War Centennial, including a visit to the 1964 New York World's Fair. Between 1966 and 1971, a legal battle ensued between the railroad and the city of Chattanooga as the former had planned to send the engine to Georgia, while the latter claimed to be the owners of the engine. After the dispute was settled, the engine was formally presented to the state of Georgia in 1971. The engine currently resides at the Southern Museum of Civil War and Locomotive History in Kennesaw, Georgia, while the Texas is currently at the North Carolina Transportation Museum in Spencer, North Carolina undergoing restoration for inclusion into an addition to house it and the cyclorama painting of the battle of Atlanta. The Texas should return to Georgia in late 2016.

The Kentucky Railway Museum consists of many pieces of L&N equipment, as well as a portion of the Lebanon Branch. The museum owns the following L&N equipment: K2A Light Pacific 4-6-2 No. 152, a steam locomotive; heavyweight coaches Nos. 2572 and 2554; an observation car; heavyweight combine No. 1603; combine coach No. 665; sleeper the Pearl River, the Pullman heavyweight 10 section sleeper-lounge Mt. Broderick which was assigned to the L&N but owned and operated by Pullman; several baggage cars; a steam-powered crane; and E-6 diesel locomotive No. 770. All of the last seven pieces of equipment listed need restoration.

The Historic Railpark and Train Museum owns or operates several pieces of L&N equipment, including an E-8 diesel locomotive, a Railway Post Office car, dining car No. 2799, a sleeping car, an observation car, along with a Jim Crow combine in need of major overhaul.

Several other museums own L&N equipment, including the Bluegrass Railroad Museum.

L&N 2132, a South Louisville Shops steam locomotive, is also on static display in Corbin, Kentucky. 2132 was moved from Bainbridge, Georgia to Corbin and underwent a full cosmetic restoration. Along with 2132 and her tender is L&N caboose 1056.[7]

The Wilderness Road Trail is a rail trail built on the ROW from Cumberland Gap National Historical Park to Ewing, Virginia.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Maury Klein (2013). History of the Louisville & Nashville Railroad. University Press of Kentucky. p. 95. ISBN 9780813146751.

- ^ "Mortgages, Charters and Other Documents of the Louisville and Nashville ..." Books.google.com. 1871. Archived from the original on January 29, 2024. Retrieved October 27, 2020.

- ^ Herr 2000, pp. 106–107.

- ^ "L&N 0-8-0 No. 2132 to come home to Kentucky". Trains.com. February 26, 2015. Archived from the original on October 15, 2023. Retrieved November 14, 2023.

- ^ "Louisville & Nashville Employes' Magazine :: Louisville and Nashville Railroad Company Records". Digital.library.louisville.edu. Archived from the original on February 14, 2017. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ "Union Station". Bhamwiki.com. Archived from the original on February 5, 2023. Retrieved February 3, 2023.

- ^ Flanary, Ron. "An "Old Reliable" Comes home to Kentucky". Trains. Vol. 83, no. March 2023. Kalmbach Media. pp. 14–21.

Further reading

edit- Castner, Charles B.; Flanary, Ron; Dorin, Patrick (1996). Louisville & Nashville Railroad: The Old Reliable (1st ed.). TLC Publishing. ISBN 978-1883089191.

- Cotterill, R. S. "The Louisville and Nashville Railroad 1861-1865", American Historical Review (1924) 29#4 pp. 700–715 in JSTOR

- Herr, Kincaid A. (2000) [1964]. The Louisville and Nashville Railroad 1850–1963. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2184-1.

- Klein, Maury (2002). History of the Louisville & Nashville Railroad. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2263-5.

- Owen, Thomas McAdory (1921). History of Alabama and Dictionary of Alabama Biography, Volume 1. Chicago, IL: The S. J. Clarke Publishing Company.

- Starr, Timothy (2024). The Back Shop Illustrated, Volume 3: Southeast and Western Regions. Privately printed.