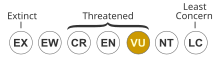

The New Zealand king shag (Leucocarbo carunculatus), also known as the rough-faced shag, king shag or kawau tūī, is a rare bird endemic to New Zealand. Some taxonomic authorities, including the International Ornithologists' Union, place this species in the genus Leucocarbo. Others place it in the genus Phalacrocorax.

| New Zealand king shag | |

|---|---|

| |

| New Zealand king shags | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Suliformes |

| Family: | Phalacrocoracidae |

| Genus: | Leucocarbo |

| Species: | L. carunculatus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Leucocarbo carunculatus (Gmelin, 1789)

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Phalacrocorax carunculatus | |

Taxonomy

editThe New Zealand king shag was formally described in 1789 by the German naturalist Johann Friedrich Gmelin in his revised and expanded edition of Carl Linnaeus's Systema Naturae. He placed it in the genus Pelecanus and coined the binomial name Pelecanus carunculatus.[2] Gmelin based his description on the "carunculated shag" that had been described in 1785 by the English ornithologist John Latham in his book A General Synopsis of Birds . Latham had based his description on a specimen in the Leverian Museum.[3] The New Zealand king shag is now one of 16 species placed in the genus Leucocarbo that was introduced in 1856 by the French naturalist Charles Lucien Bonaparte.[4][5] The name Leucocarbo combines the Ancient Greek leukos meaning "white" with the genus name Carbo introduced by Bernard Germain de Lacépède in 1799. The specific epithet is from Latin caruncula meaning "small piece of flesh".[6] The species is monotypic: no subspecies are recognised.[5]

Description

editIt is a large (76 cm long, 2.5 kg in weight) black and white cormorant with pink feet. White patches on the wings appear as bars when the wings are folded. Yellow-orange swellings (caruncles) are found above the base of the bill. The grey gular pouch is reddish in the breeding season. A blue eye-ring indicates its kinship with the other blue-eyed shags.[7] They show sexual dimorphism, with males being larger than females. This difference is noticeable as early as 17 days after hatching.[8]

Distribution and habitat

editNew Zealand king shags can be seen from the Cook Strait ferries in Queen Charlotte Sound opposite the beginning of the Tory Channel. Prehistorically, the king shag lived on coastal colonies on both the North Island and South Island of New Zealand.[9] Today, they live and breed in the coastal waters of the Marlborough Sounds at nine colonies that are occupied year-round. King shags are non-migratory birds, with their only dispersal being between colonies. They are found at Stewart Island, Trio Island, The Twins, Duffers Reef, Blumine Island, Tawhitinui, Hunia Rock, Rahuinui, and White Rocks.[10] The most commonly observed breeding colonies are Duffers Reef, North Trio Island (Kuru Pongi), White Rocks, and Tawhitinui.[8] Annual surveys show fluctuating numbers of breeding pair nests at the colonies. North Trios (Kuru Pongi) and Duffer's Reef are the largest colonies, with over 100 nests apiece. The estimated population of king shags is 792, as of 2022.[8]

Behaviour

editBreeding

editThe king shag breeding season spans from February to April, with eggs being laid as late as May. They are considered asynchronous breeders because the time of breeding is dependent on the colony the bird is in, rather than internal cues only. King shags show strong nesting site fidelity, returning to the same colony to breed on repeated years.[8] They also have high mate fidelity, with monogamous, experienced pairs being the most successful.[8] Clutches are 2-3 eggs. They do not consistently lay one egg right after another. Up to 13 days can pass between eggs.[8] If the clutch is damaged or the chicks do not survive, it is rare for replacement clutches to be laid.[8] The eggs incubate for 28–32 days before hatching. After 6 weeks, the chicks reach adult body mass, and after 8 weeks are fully feathered.[8]

Parental care lasts, on average, 21 weeks. This is measured from the last feeding of the chick. One parent remains at the nest at all times, while the other forages.[11] Both males and females take turns being the caregiver and hunter.[11] Juveniles begin to disperse from their nests anywhere from 4–12 months after hatching.[8] King shags experience high levels of juvenile mortality, especially shortly after dispersal. After one year, an estimated 54% of juveniles died.[8] Other species of cormorants experience similar levels of juvenile mortality.[12] The level of parental care strongly impacts the survival rate of juveniles, with longer parental care increasing the chances of survival.[8] Colony location can also increase juvenile survival. Colonies on the outer edge of the Marlborough Sounds saw higher mortality rates, likely due to lack of shelter against weather.[8]

Feeding

editKing shags feed by diving to catch benthic fish. These dives are 25–40 metres deep on average, but have been recorded as deep as 90 metres.[13] On average, a king shag can dive for between one and three minutes. Each dive is separated by a period of rest before diving again. These last, on average, 157 seconds but can span up to 12 minutes.[13] Individual king shags show a wide range in variation of diving durations and depths. Males and females show significantly different diving behaviour. Female king shags dive at 8–62 metres depth, and a majority of dives are done before 1 pm. Male king shags dive at a wider range of depths, 8–71 metres, and hunt later in the day, with a majority of dives occurring after 12 pm. Due to the increased depth, male king shags tend to dive for longer durations than females. Different colonies have different diving behaviours due to the different marine geology in the Marlborough Sounds. Male king shags tend to travel further from the colony to forage, but this relies heavily on the location of the colonies. Blue-eyed shags (Leucocarbo) are highly individualistic foragers, and the king shag follows this pattern.[8] The foraging range of king shags is highly dependent on the colony where they reside. King shags can forage anywhere from 8-24 kilometres away from their colonies. There is a significant difference in distance travelled between the sexes in the Tawhitinui, The Twins, and Duffers Reef colonies, with males travelling further.[8]

The most prevalent prey of king shags are witch (Pleuronectidae) and crested flounder (Bothidae).[14] These are both flatfish, and reside on the floor of the ocean. King shags typically consume their prey underwater, but there have been multiple observations of individuals surfacing carrying flatfish.[13] King shags also feed on opalfish, lemon sole, and smooth leatherjacket most commonly.[14] Smooth leatherjackets are one of the few pelagic fish found in many king shag pellets. Remnants of octopus, crab, and lobster have been found within the pellets of king shags, but it is unlikely that the birds consume them directly. Instead, it is thought to be the stomach contents of the fish eaten, and thus be a secondary dietary item.[8] Compared with other cormorants, the king shag has a reduced diversity in their diets. The high prevalence of flatfish in their pellets indicates they are feeding on primarily benthic fish, and rarely pelagic fish.

Human interference

editMussel Farms

editThe Marlborough Sounds is home to over 900 mussel farms.[15] The region produces 65,000 tonnes of green-lipped mussels annually.[15] King shags are regularly seen in small numbers around mussel farms. In non-breeding seasons, higher numbers of adults are seen at mussel farms. This is because there is no need for one adult to stay at the nest to care for chicks.[11] Mussel farms seem to have a neutral effect on king shags. There was worry that the space used for mussel farming would reduce foraging grounds for king shags, but the populations are not affected meaningfully by current aquaculture. Colony proximity to the farms is a predictor of foraging within them.[8] Both adults and juveniles have been seen roosting temporarily during the evening at mussel farms. It is thought that the structure of mussel farms, with their floating buoys, offer temporary spots to roost and preen before returning to the colony.[11] Areas surrounding the farms also see king shag foraging activity during the day. There is no indication that king shags consume the mussels, rather than the farms attract fish they then prey on.[8]

Disturbance

editFishing and travel through the Marlborough Sounds by boat are considered the largest forms of disturbance to king shags.[8] When loud boats infringe on king shag territories, they will be abandoned. Most notably, the Sentinel Rock colony of king shags was once one of the largest, and now is abandoned.[8] On average, studied individuals were disturbed once every 2 days. The highest proportion of disturbances occurred on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday.[8] On these days, activity from mussel farms is greatly reduced, but recreational fishing is popular. Recreational fishing in areas around king shag colonies threatens to drive the birds away. This could reduce available nesting space, and could cause a population reduction if not managed.[8]

References

edit- ^ BirdLife International (2018). "Leucocarbo carunculatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T22696846A133555760. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22696846A133555760.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ Gmelin, Johann Friedrich (1789). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae : secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1, Part 1 (13th ed.). Lipsiae [Leipzig]: Georg. Emanuel. Beer. p. 576.

- ^ Latham, John (1785). A General Synopsis of Birds. Vol. 3, Part 1. London: Printed for Leigh and Sotheby. p. 603.

- ^ Bonaparte, Charles Lucien (1856). "Excusion dans les divers Musées d'Allemagne, de Hollande et de Belgique, et tableaux paralléliques de l'ordre des échassiers (suite)". Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires des Séances de l'Académie des Sciences (in French). 43: 571–579 [575].

- ^ a b Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (August 2022). "Storks, frigatebirds, boobies, darters, cormorants". IOC World Bird List Version 12.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- ^ Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 223, 92. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ Schuckard, R. (2017). "New Zealand king shag". nzbirdsonline.org.nz. Retrieved 2019-05-17.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Bell, Mike (October 2022). Bell, Mike (ed.). "Kawau pāteketeke/King Shag (Leucocarbo carunculatus) Research 2018-2022. Final report on the Marine Farming Association and Seafood innovations Limited King Shag research project. Unpublished Toroa Consulting Technical Report to the Marine Farming Association and Seafood Innovations Limited" (PDF). Marine Farming. Retrieved 14 October 2024.

- ^ Rawlence, Nicolas J.; Till, Charlotte E.; Easton, Luke J.; Spencer, Hamish G.; Schuckard, Rob; Melville, David S.; Scofield, R. Paul; Tennyson, Alan J. D.; Rayner, Matt J.; Waters, Jonathan M.; Kennedy, Martyn (2017-10-01). "Speciation, range contraction and extinction in the endemic New Zealand King Shag complex". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 115: 197–209. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2017.07.011. ISSN 1055-7903.

- ^ Schuckard, Rob; Melville, David S.; Taylor, Graeme (2015). "Population and breeding census of New Zealand king shag (Leucocarbo carunculatus) in 2015" (PDF). Notornis. 62 (4): 209–218 – via birdsnz.org.

- ^ a b c d Fisher, Paul; Boren, Laura (2021). "New Zealand king shag (Leucocarbo carunculatus) foraging distribution and use of mussel farms in Admiralty Bay, Marlborough Sounds" (PDF). Notornis. 59: 105–115 – via birdsnz.org.

- ^ Hénaux, Viviane; Bregnballe, Thomas; Lebreton, Jean-Dominique (2007). "Dispersal and Recruitment during Population Growth in a Colonial Bird, the Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis". Journal of Avian Biology. 38 (1): 44–57. ISSN 0908-8857. JSTOR 30244776.

- ^ a b c Brown, Derek (2001). "Dive duration and some diving rhythms of the New Zealand king shag (Leucocarbo carunculatus)" (PDF). Notornis. 48: 177–178 – via birdsnz.org.

- ^ a b Lalas, Chris; Brown, Derek (14 October 2024). "The diet of New Zealand King Shags (Leucocarbo caranculatus) in Pelorus Sound". Nelson Marlborough Conservancy. Retrieved 14 October 2024.

- ^ a b District Council, Marlborough (14 October 2024). "Marine Farming". Marlborough District Council. Retrieved 14 October 2024.