Charles III (Spanish: Carlos Sebastián de Borbón y Farnesio;[a] 20 January 1716 – 14 December 1788) was King of Spain in the years 1759 to 1788. He was also Duke of Parma and Piacenza, as Charles I (1731–1735); King of Naples, as Charles VII; and King of Sicily, as Charles III (1735–1759). He was the fourth son of Philip V of Spain and the eldest son of Philip's second wife, Elisabeth Farnese. He was a proponent of enlightened absolutism and regalism.

| Charles III | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Portrait by Anton Raphael Mengs, c. 1761 | |||||

| King of Spain | |||||

| Reign | 10 August 1759 – 14 December 1788 | ||||

| Predecessor | Ferdinand VI | ||||

| Successor | Charles IV | ||||

| Regent | Elisabeth Farnese (1759–1760) | ||||

| Chief Ministers | |||||

| King of Naples and Sicily as Charles VII of Naples and III of Sicily | |||||

| Reign | 3 July 1735 – 6 October 1759 | ||||

| Coronation | 3 July 1735, Palermo Cathedral | ||||

| Predecessor | Charles VI & IV | ||||

| Successor | Ferdinand IV & III | ||||

| Duke of Parma and Piacenza as Charles I | |||||

| Reign | 26 February 1731 – 3 October 1735 | ||||

| Predecessor | Antonio Farnese | ||||

| Successor | Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor | ||||

| Regent | Dorothea Sophie of Palatinate-Neuburg (1731-1735) | ||||

| Born | 20 January 1716 Royal Alcazar of Madrid, Spain | ||||

| Died | 14 December 1788 (aged 72) Royal Palace of Madrid, Spain | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue Detail | |||||

| |||||

| House | Bourbon | ||||

| Father | Philip V of Spain | ||||

| Mother | Elisabeth Farnese | ||||

| Religion | Catholic Church | ||||

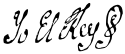

| Signature |  | ||||

In 1731, the 15-year-old Charles became Duke of Parma and Piacenza following the death of his childless grand-uncle Antonio Farnese. In 1734, at the age of 18, he led Spanish troops in a bold and almost entirely bloodless march down Italy to seize the Kingdom of Naples and Kingdom of Sicily and enforce the Spanish claim to their thrones. In 1738, he married the Princess Maria Amalia of Saxony, daughter of Augustus III of Poland, who was an educated, cultured woman. The couple had 13 children, eight of whom reached adulthood. They resided in Naples for 19 years. Charles gained valuable experience in his 25-year rule in Italy, so that he was well prepared as the monarch of the Spanish Empire. His policies in Italy prefigured ones he would put in place in his 30-year rule of Spain.[1]

Charles succeeded to the Spanish throne in 1759 upon the death of his childless half-brother Ferdinand VI. As king of Spain, Charles III made far-reaching reforms to increase the flow of funds to the crown and defend against foreign incursions on the empire. He facilitated trade and commerce, modernized agriculture and land tenure, and promoted science and university research. He implemented regalist policies to increase the power of the state regarding the church. During his reign, he expelled the Jesuits from the Spanish Empire[2] and fostered the Enlightenment in Spain. Charles launched enquiries into the Iberian Peninsula's Muslim past, even after succeeding to the Spanish throne. He strengthened the Spanish Army and the Spanish Navy. Although he did not achieve complete control over Spain's finances, and was sometimes obliged to borrow to meet expenses, most of his reforms proved successful in providing increased revenue to the crown and expanding state power, leaving a lasting legacy.[3]

In the Spanish Empire his regime enacted a series of sweeping reforms with the aim of bringing the overseas territories under firmer control by the central government, reversing the trend toward local autonomy, and gaining more control over the Church. Reforms including the establishment of two new viceroyalties, realignment of administration into intendancies, creating a standing military, establishing new monopolies, revitalizing silver mining, excluding American-born Spaniards (criollos) from high civil and ecclesiastical offices, and eliminating many privileges (fueros) of clergy.[4]

Historian Stanley Payne writes that Charles "was probably the most successful European ruler of his generation. He had provided firm, consistent, intelligent leadership. He had chosen capable ministers ... [his] personal life had won the respect of the people."[5] John Lynch's assessment is that in Bourbon Spain "Spaniards had to wait half a century before their government was rescued by Charles III."[6]

Spanish imperial legacy

editIn 1713, the Treaty of Utrecht concluded the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–14) and reduced the political and military power of Spain, which the House of Bourbon had ruled since 1700. Under the terms of the treaty, the Spanish Empire retained its American territories and the Philippines, but ceded the Spanish Netherlands, the kingdoms of Naples and Sardinia, the Duchy of Milan, and the State of Presidi to Habsburg Austria. The House of Savoy gained the Kingdom of Sicily, and the Kingdom of Great Britain gained the island of Menorca and the fortress at Gibraltar.

In 1700, Charles's father, originally a French Bourbon prince, Philip of Anjou, became King of Spain as Philip V. For the remainder of his reign (1700–46), he continually attempted to regain the ceded territories in Europe. In 1714, after the death of the king's first wife, the Princess Maria Luisa Gabriella of Savoy, the Piacenza Cardinal Giulio Alberoni successfully arranged the swift marriage between Philip and the ambitious Elisabeth Farnese, niece and stepdaughter of Francesco Farnese, Duke of Parma. Elisabeth and Philip married on 24 December 1714; she quickly proved a domineering consort and influenced King Philip to make Cardinal Giulio Alberoni the prime minister of Spain in 1715.

On 20 January 1716, Elisabeth gave birth to the Infante Charles of Spain at the Royal Alcázar of Madrid. He was fourth in line to the Spanish throne, after three elder half-brothers: the Infante Luis, Prince of Asturias (who ruled briefly as Louis I of Spain before dying in 1724); the Infante Felipe (who died in 1719); and Ferdinand (the future Ferdinand VI). Because the Duke Francesco of Parma and his heir were childless, Elisabeth sought the Duchy of Parma and Piacenza for Charles, since he was unlikely to be king of Spain. She also sought for him the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, because Gian Gastone de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany (1671–1737) was also childless. He was a distant cousin of hers, related via her great-grandmother Margherita de' Medici, giving Charles a claim to the title through that lineage.

Early years

editThe birth of Charles encouraged Prime Minister Alberoni to start laying out grand plans for Europe. In 1717 he ordered the Spanish invasion of Sardinia. In 1718, Alberoni also ordered the invasion of Sicily, which was also ruled by the House of Savoy. In the same year Charles's first sister, Infanta Mariana Victoria was born on 31 March. In reaction to the Quadruple Alliance of 1718, the Duke of Savoy then joined the Alliance and went to war with Spain. This war led to the dismissal of Alberoni by Philip in 1719. The Treaty of The Hague of 1720 included the recognition of Charles as heir to the Italian Duchies of Parma and Piacenza.

Charles's half-brother, Infante Philip Peter, died on 29 December 1719, putting Charles third in line to the throne after Luis and Ferdinand. He would retain his position behind these two until they died and he succeeded to the Spanish throne. His second full brother, Infante Philip of Spain, was born on 15 March 1720.

Beginning in 1721, King Philip had been negotiating with the Duke of Orléans, the French regent, to arrange three Franco-Spanish marriages that could potentially ease tense relations. The young Louis XV of France would marry the three-year-old Infanta Mariana Victoria and thus she would become Queen of France; Charles's half-brother Louis would marry the fourth surviving daughter of the regent, Louise Élisabeth d'Orléans. Charles himself would be engaged to Philippine Élisabeth d'Orléans, who was the fifth surviving daughter of the Duke of Orléans.

In 1726 Charles met Philippine Élisabeth for the first time; Elisabeth Farnese later wrote to the regent and his wife regarding their meeting:

"I believe, that you will not be displeased to learn of her first interview with her little husband. They embraced very affectionately and kissed one another, and it appears to me that he does not displease her. Thus, since this evening they do not like to leave one another. She says a hundred pretty things; one would not credit the things that she says unless one heard them. She has the mind of an angel, and my son is only too happy to possess her . . . She has charged me to tell you that she loves you with all her heart and that she is quite content with her husband."

And to the duchesse d'Orléans she writes:

"I find her the most beautiful and most lovable child in the world. It is the most pleasing thing imaginable to see her with her little husband: how they caress one another and how they love one another already. They have a thousand little secrets to tell one another, and they cannot part for an instant."[7]

Out of these proposed marriages, only Louis and Louise Élisabeth would wed. Elisabeth Farnese looked for other potential brides for her eldest son. For this, she looked to Austria, Spain's principal opponent for influence on the Italian Peninsula. She proposed to Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor, that the Infante Charles marry the eight-year-old Archduchess Maria Theresa and that her second surviving son, the Infante Philip, marry the seven-year-old Archduchess Maria Anna.

The alliance of Spain and Austria was signed on 30 April 1725 and included Spanish support for the Pragmatic Sanction, a document drafted by Emperor Charles in 1713 to assure support for Maria Theresa in the succession to the throne of the Habsburgs. The emperor also relinquished all claims to the Spanish throne and promised to support Spain in its attempts to regain Gibraltar. The ensuing Anglo-Spanish War stopped the ambitions of Elisabeth Farnese, and the marriage plans were abandoned with the signing of the Treaty of Seville on 9 November 1729. Provisions of the treaty did allow the Infante Charles the right to occupy Parma, Piacenza, and Tuscany by force if necessary.

After the Treaty of Seville, Philip V disregarded its provisions and formed an alliance with France and the Kingdom of Great Britain. Antonio Farnese, the Duke of Parma, died on 26 February 1731 without naming an heir. This was because the widow of Antonio, Enrichetta d'Este was thought to have been pregnant at the time of his death. The Duchess was examined by many doctors without any confirmation of her pregnancy. As a result, the Second Treaty of Vienna on 22 July 1731 officially recognized the young Infante Charles as Duke of Parma and Piacenza.

The duchy was occupied by Count Carlo Stampa, who served as the lieutenant of Parma for the young Charles. Charles was from then on known as HRH Don Charles of Spain (or Borbón), Duke of Parma and Piacenza, Infante of Spain. Since he was still a minor, his maternal grandmother, Dorothea Sophie of Neuburg, was named regent.

Rule in Italy

editArrival in Italy

editAfter a solemn ceremony in Seville, Charles was given the épée d'or ("sword of gold") by his father; the sword had been given to Philip V of Spain by his grandfather Louis XIV before his departure to Spain in 1700. Charles left Spain on 20 October 1731 and traveled overland to Antibes; he then sailed to Tuscany, arriving at Livorno on 27 December 1731. His cousin Gian Gastone de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, was named his co-tutor and despite Charles being the second in line to inherit Tuscany, the Grand Duke still gave him a warm welcome. En route to Florence from Pisa, Charles was taken ill with smallpox.[8] Charles made a grand entrance to the Medici capital of Florence on 9 March 1732 with a retinue of 250 people. He stayed with his host at the ducal residence, the Palazzo Pitti.[8]

Gian Gastone staged a fête in honor of the Patron Saint of Florence, St. John the Baptist, on 24 June. At this fête Gian Gastone named Charles his heir, giving him the traditional Tuscan title of Hereditary Prince of Tuscany, and Charles paid homage to the Florentine senate, as was the tradition for heirs to the Tuscan throne. When Emperor Charles VI heard about the ceremony, he was enraged that Gian Gastone had not informed him, since he was overlord of Tuscany and the nomination should have been his prerogative. Despite the celebrations, Elisabeth Farnese urged her son to go on to Parma, which he did in October 1732, where he was warmly greeted. On the front of the ducal palace in Parma was written Parma Resurget (Parma shall rise again). At the same time the play La Venuta di Ascanio in Italia was created by Carlo Innocenzo Frugoni. It was later performed at the Teatro Farnese in the city.[9][10]

Conquest of Naples and Sicily

editIn 1733, the death of Augustus II, King of Poland, sparked a succession crisis in Poland. France supported one pretender, and Austria and Russia another. France and Savoy formed an alliance to acquire territory from Austria. Spain, which had allied with France in late 1733 (the Bourbon Compact), also entered the conflict. Charles's mother, as regent, saw the opportunity to regain the Kingdoms of Naples and Sicily, which Spain had lost in the Treaty of Utrecht.

On 20 January 1734, Charles, now 18, reached his majority, and was "free to govern and to manage in a manner independent its states".[11] He was also named commander of all Spanish troops in Italy, a position he shared with the Duke of Montemar. On 27 February, King Philip declared his intention to capture the Kingdom of Naples, claiming he would free it of "excessive violence by the Austrian Viceroy of Naples, oppression, and tyranny".[12] Charles, now "Charles I of Parma", was to be in charge. Charles inspected the Spanish troops at Perugia, and marched toward Naples on 5 March. The army passed through the Papal States then ruled by Clement XII.[11]

The Austrians, already fighting the French and Savoyard armies to retain Milan, had only limited resources for the defense of Naples and were divided on how best to oppose the Spanish. The Emperor wanted to keep Naples, but most of the Neapolitan nobility was against him, and some conspired against his viceroy. They hoped that Philip would give the kingdom to Charles, who would be more likely to live and rule there, rather than having a viceroy and serve a foreign power. On 9 March the Spanish took Procida and Ischia, two islands in the Bay of Naples. A week later they defeated the Austrians at sea. On 31 March, his army closed in on the Austrians in Naples. The Spanish flanked the defensive position of the Austrians under general Traun and forced them to withdraw to Capua. This allowed Charles and his troops to advance on to the city of Naples itself.

The Austrian viceroy, Giulio Borromeo Visconti, and the commander of his army, Giovanni Carafa , left some garrisons holding the city's fortresses and withdrew to Apulia. There they awaited reinforcements sufficient to defeat the Spanish. The Spanish entered Naples and laid siege to the Austrian-held fortresses. During that interval, Charles received the compliments of the local nobility, and the city keys and the privilege book from a delegation of the city's elected officials.[13] Chronicles of the time reported that Naples was captured "with humanity" and that the combat was only due to a general climate of courtesy between the two armies, often under the eyes of the Neapolitans that approached with curiosity

The Spanish took the Carmine Castle on 10 April; Castel Sant'Elmo fell on 27 April; the Castel dell'Ovo on 4 May, and finally the Castel Nuovo on 6 May. This all occurred even though Charles had no military experience, seldom wore uniforms, and could only with difficulty be persuaded to witness a review.

Arrival in Naples and Sicily, recognition as king 1734-35

editCharles had his triumphant entrance to Naples on 10 May 1734, through the old city gate at Capuana surrounded by the city councilors along with a group of people who threw money to the locals. The procession went on through the streets and ended up at the Naples Cathedral, where Charles received a blessing from the local archbishop, Cardinal Pignatelli. Charles took up residence at the Royal Palace of Naples, which had been built by his ancestor, Philip III of Spain.

Two chroniclers of the era, the Florentine Bartolomeo Intrieri, and the Venetian Cesare Vignola made conflicting reports on the view of the situation by Neapolitans. Intrieri writes that the arrival was a historic event and that the crowd cried out that "His Royal Highness is beautiful, that his face is as the one of San Gennaro on the statue that the representative".[14] Vignola wrote in contrast that "there were only some acclamations", and that the crowd applauded with "a lot of languors" and only "to incite those that threw the money to throw it in more abundance".[15]

Charles's father, King Philip V of Spain, wrote the following letter to Charles.

The letter began with the words "To the King of Naples, My Son, and My Brother".[16] Charles was unique in the fact that he was the first ruler of Naples to actually live there, after two centuries of viceroys. However, Austrian resistance had not yet been completely eliminated. The emperor had sent reinforcements to Naples directed by the Prince of Belmonte, which arrived at Bitonto.

Spanish troops led by the Count of Montemar attacked the Austrians on 25 May 1734 at Bitonto, and achieved a decisive victory. Belmonte was captured after he fled to Bari, while other Austrian troops were able to escape to the sea. To celebrate the victory, Naples was illuminated for three nights, and on 30 May, the Duke of Montemar, Charles's army commander, was named the Duke of Bitonto.[17] Today there is an obelisk in the city of Bitonto commemorating the battle constructed and designed by Giovanni Antonio Medrano.

After the fall of Reggio Calabria on 20 June, Charles also conquered the towns of L'Aquila (27 June) and Pescara (28 July). The last two Austrian fortresses were Gaeta and Capua. The Siege of Gaeta, which Charles observed, ended on 6 August. Three weeks later, the Duke of Montemar left the mainland for Sicily where they arrived in Palermo on 2 September 1734, beginning a conquest of the island's Austrian-held fortresses that ended in early 1735. Capua, the only remaining Austrian stronghold in Naples, was held by von Traun until 24 November 1734. In the kingdom, independence from the Austrians was popular.

In 1735, pursuant to the treaty ending the war, Charles formally ceded Parma to Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI in exchange for his recognition as King of Naples and Sicily. Following the loss of Parma, Charles removed the Farnese Collection to Naples.

Conflict with the Holy See

editDuring the early years of Charles's reign, the Neapolitan court was engaged in a dispute with the Holy See over jurisdiction, clerical appointments, and revenues. The Kingdom of Naples was an ancient fief of the Papal States. For this reason, Pope Clement XII considered himself the only one entitled to invest the king of Naples, and so he did not recognize Charles of Bourbon as a legitimate sovereign. Through the apostolic nuncio, the Pope let Charles know he did not consider valid the nomination received by him from Charles's father, Philip V, King of Spain. In response, a committee headed by the Tuscan lawyer Bernardo Tanucci in Naples concluded that papal investiture was not necessary because the crowning of a king could not be considered a sacrament.[18]

The situation worsened when, in 1735, just a few days before the coronation of Charles, the Pope chose to accept the traditional offering of a Hackney horse from the Holy Roman Emperor rather than from Charles. The Hackney was a white mare and a sum of money which the King of Naples offered the Pope as feudal homage every 29 June, at the feast of Saints Peter and Paul. The reason for this choice was that Charles had not yet been recognized as ruler of the Kingdom of Naples by a peace treaty, and so the Emperor was considered still de jure King of Naples. Receiving the Hackney from the Holy Roman Empire was common while receiving it from a Bourbon was unusual. The Pope, therefore, considered the first option a less dramatic gesture, and in doing so provoked the wrath of the religious Spanish infante.

Meanwhile, Charles had landed in Sicily. Although the Bourbon conquest of the island was not complete, he was crowned King of the Two Sicilies ("utriusque Siciliae rex") on 3 July in the ancient Palermo Cathedral, after having traveled overland to Palmi, and by sea from Palmi to Palermo. The coronation bypassed the authority of the Pope thanks to the apostolic legation of Sicily, a medieval privilege which ensured the island a special legal autonomy from the Church. Thus, the papal legate did not attend the ceremony as Charles would have wanted.[19]

In March 1735 a new discord developed between Rome and Naples. In Rome, it was discovered that the Bourbons had confined Roman citizens in the basement of Palazzo Farnese, which was the personal property of King Charles; people were brought there to impress them into the newborn Neapolitan army. Thousands of inhabitants in the suburb of Trastevere stormed the palace to liberate them. The riot then degenerated into pillage. Next, the crowd directed itself toward the embassy of Spain in Piazza di Spagna. During the clashes that followed, several Bourbon soldiers were killed, including an officer. The disturbances spread to the town of Velletri, where the population attacked Spanish troops on the road to Naples.

The episode was perceived as a serious affront to the Bourbon court. Consequently, the Spanish and Neapolitan ambassadors left Rome, the seat of the papacy, while apostolic nuncios were dismissed from Madrid and Naples. The regiments of Bourbon troops invaded the Papal States. The threat was such that some of the gates of Rome were barred and the civil guard was doubled. Velletri was occupied and forced to pay 8000 crowns for the occupation. Ostia was sacked, while Palestrina avoided the same fate by the payment of a ransom of 16,000 crowns.

The commission of cardinals to whom the case was assigned decided to send a delegation of prisoners of Trastevere and Velletri to Naples as reparations. The papal subjects were punished with just a few days in jail and then, after seeking royal pardon, were granted it.[19] The Neapolitan king subsequently managed to iron out his differences with the Pope, after long negotiations, through the mediation of its ambassador in Rome, Cardinal Acquaviva, the archbishop Giuseppe Spinelli and the chaplain Celestino Galiani. The agreement was achieved on 12 May 1738.

After the death of Pope Clement in 1740, he was replaced by Pope Benedict XIV, who the following year allowed the creation of a concordat with the Kingdom of Naples. This allowed the taxation of certain property of the clergy, the reduction of the number of the ecclesiastical, and the limitation of their immunity and autonomy of justice via the creation of a mixed tribunal.[20][clarification needed]

Choice of name

editCharles was the seventh king of that name to rule Naples, but he never styled himself Charles VII. He was known simply as Charles of Bourbon (Italian: Carlo di Borbone). This was intended to emphasize that he was the first King of Naples to live there, and to mark the discontinuity between him and previous rulers named Charles, specifically his predecessor, the Habsburg Charles VI.[citation needed]

In Sicily, he was known as Charles III of Sicily and of Jerusalem, using the ordinal III rather than V. The Sicilian people had not recognized Charles I of Naples (Charles d'Anjou) as their sovereign (they rebelled against him), nor Emperor Charles, whom they also disliked.[citation needed]

| Carolus Dei Gratia Rex utriusque Siciliae[21], & Hyerusalem, &c. Infans Hispaniarum, Dux Parmae, Placentiae, Castri, &c. Ac Magnus Princeps Haereditarius Hetruriae, &c.[22] | Charles, by the Grace of God King of Naples, Sicily and of Jerusalem, etc. Infante of Spain, Duke of Parma, Piacenza and of Castro etc. Great Hereditary Prince of Tuscany. |

| Family of Philip V including Charles in 1743 |

|---|

Peace with Austria

editA preliminary peace with Austria was concluded on 3 October 1735. However, the peace was not finalized until three years later with the Treaty of Vienna (1738), ending the War of the Polish Succession.

Naples and Sicily were ceded by Austria to Charles, who gave up Parma and Tuscany in return. (Charles had inherited Tuscany in 1737 on the death of Gian Gastone.) Tuscany went to Emperor Charles VI's son-in-law Francis Stephen, as compensation for ceding the Duchy of Lorraine to the deposed Polish King Stanislaus I.

The treaty included the transfer to Naples of all the inherited goods of the House of Farnese. He took with him the collection of artwork, the archives and the ducal library, the cannons of the fort, and even the marble stairway of the ducal palace.[23]

War of the Austrian Succession

editThe peace between Charles and Austria was signed in Vienna in 1740. That year, Emperor Charles died leaving his Kingdoms of Bohemia and Hungary (along with many other lands) to his daughter Maria Theresa; he had hoped the many signatories to the Pragmatic Sanction would not interfere with this succession. However, this was not the case, and the War of the Austrian Succession broke out. France was allied with Spain and Prussia, all of whom were against Maria Theresa. Maria Theresa was supported by Great Britain, ruled by George II, and the Kingdom of Sardinia, which was then ruled by Charles Emmanuel III of Sardinia.

Charles had wanted to stay neutral during the conflict, but his father wanted him to join in and gather troops to aid the French. Charles arranged for 10,000 Spanish soldiers that were to be sent to Italy under the command of the Duke of Castropignano, but they were obliged to retreat when a Royal Navy squadron under Commodore William Martin threatened to bombard Naples if they did not stay out of the conflict.[24]

The decision to remain neutral was again revived and was poorly received by the French and his father in Spain. Charles's parents encouraged him to take arms as his brother Infante Felipe had done. After publishing a proclamation on 25 March 1744 reassuring its subjects, Charles took the command of an army against the Austrian armies of the prince of Lobkowitz, who were at that point marching for the Neapolitan border.

In order to oppose the small but powerful pro-Austrian party in Naples, a new council was formed under the direction of Tanucci that resulted in the arrest of more than 800 people. In April Maria Theresa addressed the Neapolitans with a proclamation in which she promised pardons and other benefits for those who rose against the "usurpers", meaning the Bourbons.[25]

The participation of Naples and Sicily in the conflict resulted, on 11 August in the decisive Battle of Velletri, where Neapolitan troops directed by Charles and the Duke of Castropignano, and Spanish troops under the Count of Gages, defeated the Austrians of Lobkowitz, who retreated with heavy losses. The courage shown by Charles caused the King of Sardinia, his enemy, to write that "he revealed a worthy consistency of his blood and that he behaved gloriously".[26]

The victory at Velletri assured Charles the right to give the title Duke of Parma to his younger brother Infante Felipe. This was recognized in the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle signed in 1748; it was not until the next year that Infante Felipe would officially be the Duke of Parma, Piacenza, and Guastalla.

Impact of rule in Naples and Sicily

editCharles left a lasting legacy on his kingdom, introducing reforms during his reign. In Naples, Charles began internal reforms that he later continued in peninsular Spain and the ultramarine Spanish Empire. His chief minister in Naples, Bernardo Tanucci, had a considerable influence over him. Tanucci had found a solution to Charles's acceding to the throne, but then implemented a major regalist policy toward the Church, substantially limiting the privileges of the clergy, whose vast possessions enjoyed tax exemption and their own jurisdiction. His realm was financially a backward, underdeveloped stagnant agrarian economy, with 80% of the land being owned or controlled by the church and therefore tax-exempt. Landlords often registered their properties with the church to benefit from tax exemptions. Their rural tenants were under their landlords' control rather than royal jurisdiction. Taxes were collected by tax farming through low paid employees who supplemented their income by the exploitation of their position. "Smuggling and corruption were institutionalized at all levels."[27]

Charles encouraged the development of skilled craftsmen in Naples and Sicily, after centuries of foreign domination. Charles is recognized for having recreated the "Neapolitan nation", building an independent and sovereign kingdom.[28] He also instituted reforms that were more administrative, more social and more religious than the kingdom had seen for a long time. In 1746 the Inquisition was introduced in domains bought by the Cardinal Spinelli, though this was not popular and required intervention by Charles.

Charles was the most popular king the Neapolitans had had for many years. He was very supportive of the people's needs, regardless of class, and has been hailed[29] as an Enlightenment king. Among the initiatives aimed at bringing the kingdom out of difficult economic conditions, Charles created the "commerce council" that negotiated with the Ottomans, Swedes, French, and Dutch. He also founded an insurance company and took measures to protect the forests, and tried to start the extraction and exploitation of the natural resources.

On 3 February 1740, King Charles issued a proclamation containing 37 paragraphs, in which Jews were formally invited to return to Sicily, from where they had been brutally expelled in 1492. This move had a little practical effect: though a few Jews did come to Sicily, though there was no legal impediment to their living there, they felt their lives insecure, and they soon went back to Turkey. Despite the King's goodwill, the Jewish community of Sicily which had flourished in the Middle East was not re-established. Still, this was a significant symbolic gesture, the King clearly repudiating a past policy of religious intolerance. Moreover, the expulsion of the Jews from Sicily had been an application of the Spanish Alhambra Decree - which would be repudiated in Spain itself only much later.

The Kingdom of Naples remained neutral during the Seven Years' War (1756–1763). The British Prime Minister, William Pitt wanted to create an Italian league where Naples and Sardinia would fight together against Austria, but Charles refused to participate. This choice was sharply criticized by the Neapolitan Ambassador in Turin, Domenico Caraccioli, who wrote:

"The position of Italian matters is not more beautiful; but it is worsened by the fact that the King of Naples and the King of Sardinia, adding troops to larger forces of the others, could oppose itself to the plans of their neighbors; to defend itself against the dangers of the peace of the enemies themselves they were in a way united, but they are separated by their different systems of government."[30]

With the Republic of Genoa relations were stretched: Pasquale Paoli, general of Corsican pro-independence rebels, was an officer of the Neapolitan army and the Genoese suspected that he received the assistance of the Kingdom of Naples.

He constructed a collection of palaces in and around Naples. Charles was in awe of the Palace of Versailles and the Royal Palace of Madrid in Spain (the latter being modeled on Versailles itself). He undertook and oversaw the construction of one of Europe's most lavish palaces, the Royal Palace of Caserta (Reggia di Caserta). Construction ideas for the stunning palace started in 1751 when he was 35 years old. The site had previously been home to a small hunting lodge, as had Versailles, which he was fond of because it reminded him of the Royal Palace of La Granja de San Ildefonso in Spain. Caserta was also much influenced by his wife, the very cultured Maria Amalia of Saxony. The site of the palace was also far away from the large volcano of Mount Vesuvius, which was a constant threat to the capital, as was the sea. Charles himself laid the foundation stone of the palace amid many festivities on his 36th birthday, 20 January 1752. Other buildings he had built in his kingdom were the Palace of Portici (Reggia di Portici), he had Giovanni Antonio Medrano design the Teatro di San Carlo—constructed in just 270 days—and the Palace of Capodimonte (Reggia di Capodimonte); he also had the Royal Palace of Naples renovated. He and his wife had the Capodimonte porcelain Factory constructed in the city. He also founded the Accademia Ercolanese and the National Archaeological Museum, Naples, which still operates today.

During his rule the Roman cities of Herculaneum (1738), Stabiae and Pompeii (1748) were re-discovered. The king encouraged their excavation and continued to be informed about findings even after moving to Spain. Camillo Paderni who was in charge of excavated items at the king's palace in Portici was also the first to attempt in reading obtained scrolls from the Villa of the Papyri in Herculaneum.[31]

After Charles departed for Spain, Minister Tanucci presided over the Council of Regency that ruled until Charles' third son Ferdinand reached 16, the age of majority.

King of Spain, 1759–1788

editCharles was not expected to ascend to the throne of Spain, since his father had sons from his first wife who were more likely to rule. As the first son of his father's second wife, Charles benefited from his mother's ambition that he have a kingdom to rule, an experience that served him well when he ascended to the throne of Spain and ruled the Spanish Empire.

Accession to the Spanish throne

editAt the end of 1758, Charles's half brother Ferdinand VI was displaying the same symptoms of depression that their father used to suffer from. Ferdinand lost his devoted wife, Barbara of Portugal, in August 1758, and fell into deep mourning for her. He named Charles his heir presumptive on 10 December 1758 before leaving Madrid to stay at Villaviciosa de Odón, where he died on 10 August 1759.

At that point, Charles was proclaimed King of Spain under the name of Charles III of Spain. Upon gaining the Spanish throne, he abdicated those of Naples and Sicily, respecting the third Treaty of Vienna that stated he would not be able to join the Neapolitan and Sicilian territories to the Spanish throne.

Continued connection to Italy

editCharles was later given the title of Lord of the Two Sicilies. The Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, which Charles had not ratified, foresaw the eventuality of his accession to Spain; thus Naples and Sicily went to his brother Philip, Duke of Parma, while the possessions of the latter were divided between Maria Theresa (Parma and Guastalla) and the King of Sardinia (Piacenza).

Determined to maintain the hold of his descendants on the court of Naples, Charles undertook lengthy diplomatic negotiations with Maria Theresa, and in 1758 the two signed the Fourth Treaty of Versailles, by which Austria formally renounced the Italian Duchies. Charles Emmanuel III of Sardinia, however, continued to pressure on the possible gain of Piacenza and even threatened to occupy it.

In order to defend the Duchy of Parma from Charles Emmanuel's threats, Charles deployed troops on the borders of the Papal States. Thanks to the mediation of Louis XV, Charles Emmanuel renounced his claims to Piacenza in exchange for financial compensation. Charles thus assured the succession of one of his sons, the protection of his brother Philip's duchy and, at the same time, reduced Charles Emmanuel's ambitions. According to Domenico Caracciolo, this was "a fatal blow to the hopes and designs of the king of Sardinia".[32]

The eldest son of Charles, Infante Philip, Duke of Calabria, had learning difficulties and was thus taken out of the line of succession to any throne; he died in Portici, where he had been born, in 1747. The title of Prince of Asturias was given to Charles, the second-born. The right of succession to Naples and Sicily was reserved for his third son, Ferdinand; he would stay in Italy while his father was in Spain. Charles formally abdicated the crowns of Naples and Sicily on 6 October 1759 in favor of Ferdinand. Charles left his son's education and care to a regency council composed of eight members, which would govern the kingdom until the young king was 16 years old. Charles and his wife arrived in Barcelona on 7 October 1759.

Ruler of Spain

editHis twenty years in the Italian Peninsula had been very fruitful, and he came to the throne of Spain with significant experience.[33] Internal politics, as well as diplomatic relationships with other countries, underwent complete reform. Charles represented a new type of ruler, who followed Enlightened absolutism. This was a form of absolute monarchy or despotism in which rulers embraced the principles of the Enlightenment, especially its emphasis upon rationality, and applied them to their territories. They tended to allow religious toleration, freedom of speech and the press, and the right to hold private property. Most fostered the arts, sciences, and education. Charles shared these ideals with other monarchs, including Maria Theresa of Austria, her son Joseph, and Catherine the Great of Russia.

The principles of the Enlightenment were applied to his rule in Naples, and he intended to do the same in Spain though on a much larger scale. Charles went about his reform along with the help of the Marquis of Esquilache, Count of Aranda, Count of Campomanes, Count of Floridablanca, Ricardo Wall and the Genoan aristocrat Jerónimo Grimaldi.

Under Charles's reign, Spain began to be recognized as a nation state rather than a collection of kingdoms and territories with a common sovereign. This was a long process that his Bourbon predecessors had initiated. Philip V had abolished the special privileges (fueros) of the Kingdoms of Aragon and Valencia, subordinating them to the Crown of Castile and ruled by the Council of Castile. In the Nueva Planta decrees, Philip V also disbanded the Generalitat de Catalunya, abolished its Constitutions, banned the Catalan language from any official use and mandated the use of Castilian Spanish in legal affairs. He incorporated these formerly privileged entities into the Cortes of Castile, in effect, the Cortes of Spain.[34] When Charles III became King of Spain, he further solidified the standing of the nation as a single political entity. He created the national anthem and a flag, a capital city worthy of the name, and the construction of a network of coherent roads converging on Madrid. On 3 September 1770 Charles III declared that the Marcha Real was to be used in official ceremonies. It was Charles who chose the colors of the present flag of Spain: two red stripes above and below a central yellow stripe double in width and the arms of Castile and León. The flag of the military navy was introduced by the king on 28 May 1785. Until then, Spanish vessels sported the white flag of the Bourbons with the arms of the sovereign. Charles replaced it due to his concern that it looked too similar to the flags of other nations.

Military conflicts

editBourbon Spain, like their Habsburg predecessors, were drawn into European conflicts, not necessarily to Spain's benefit. The traditional friendship with Bourbon France brought about the idea that the power of Great Britain would decrease and that of Spain and France would do the opposite; this alliance was marked by a Family Compact signed on 15 August 1761 (called the "Treaty of Paris"). Charles had become deeply concerned that British success in the Seven Years War would upset the balance of power, and they would soon seek to declare war against the Spanish Empire as well. The French government ceded its largest territory in North America, New France, to Britain as a result of the conflict.

In early 1762, Spain entered the war. The major Spanish objectives to invade Portugal and capture Jamaica were both failures. Britain and Portugal not only repulsed the Spanish attack on Portugal, but captured the cities of Havana, Cuba, a strategic port for all of Spanish America, and Manila, in the Philippines, Spain's stronghold for its Asian trade and colony of strategic islands. Charles III wanted to keep fighting the following year, but he was persuaded by the French leadership to stop. In the 1763 Treaty of Paris, Spain ceded Florida to Great Britain in exchange for the return of Havana and Manila. This was partly compensated by the acquisition of French Louisiana, given to Spain by France as compensation for Spain's war losses. Britain's easy victories in capturing Spanish ports prompted Spain to create a standing army and local militias in key parts of Spanish America and fortify vulnerable forts.[35]

In the Falklands Crisis of 1770 the Spanish came close to war with Great Britain after expelling the British garrison of the Falkland Islands. However, Spain was forced to back down when it realized its vulnerability to the British Royal Navy and France declined to support Spain.[36]

On 7 July 1771, Tadeo de Medrano y Acedo wrote a letter to Joaquín López de Zúñiga y Castro, 12th Duke of Béjar. In this letter, Tadeo informs the Duke of a military campaign in which Charles III of Spain led an army of over 14,000 men, including Turks and Moors, and recounts how he had the fortune to witness the first shots fired during the battle.[37]

The invasion of Algiers in 1775 was ordered by Charles, who was attempting to demonstrate to the Barbary States the power of the revitalized Spanish military after the disastrous Spanish experience in the Seven Years' War. The assault was also meant to demonstrate that Spain would defend its North African territories against any Ottoman or Moroccan encroachment.

Continuing territorial disputes with Portugal led to the First Treaty of San Ildefonso, on 1 October 1777, in which Spain got Colonia del Sacramento, in present-day Uruguay, and the Misiones Orientales, in present-day Brazil, but not the western regions of Brazil, and also the Treaty of El Pardo, on 11 March 1778, in which Spain again conceded that Portuguese Brazil had expanded far west of the longitude specified in the Treaty of Tordesillas, and in return Portugal ceded present-day Equatorial Guinea to Spain.[38]

Concerns about the intrusions of British and Russian merchants into Spain's colonies in California prompted the extension of Franciscan missions to Alta California, as well as presidios.[39][40]

The rivalry with Britain also led him to support the American revolutionaries in their war of independence (1776-1783), despite his misgivings about the example it would set for Spain's overseas territories. During the war, Spain recovered Menorca and West Florida in several military campaigns, but failed in their attempt to capture Gibraltar. Spanish military operations in West Florida and on the Mississippi River helped the Thirteen Colonies secure their southern and western frontiers during the war. The capture of Nassau in the Bahamas enabled Spain to also recover East Florida during peace negotiations. The Treaty of Paris of 1783 confirmed the recovery of the Floridas and Menorca and restricted the actions of British commercial interests in Central America.[41]

Domestic political policies

editCharles had able and enlightened ministers who helped craft his reform policies. During his early rule in Spain, he appointed Italians, including the Marquess of Esquilache and Duke of Grimaldi, who supported reforms by the Count of Campomanes. The Count of Floridablanca was an important minister late in Charles's reign, who was carried over as minister after Charles's death. Also important was the Count of Aranda, who dominated the Council of Castile (1766-1773).[42]

His internal government was, on the whole, beneficial to the country. He began by compelling the people of Madrid to give up emptying their slops out of the windows, and when they objected he said they were like children who cried when their faces were washed. At the time of his accession to Spain, Charles named secretary to the Finances and Treasurer the Marquis of Esquillache and both realized many reforms. The Spanish Army and Navy were reorganized despite the losses from the Seven Years War.

Charles also eliminated the tax on flour and generally liberalized most commerce. Despite this action, it provoked the overlord to charge high prices because of the "monopolizers" speculating on the bad harvests of the previous years. On 23 March 1766, his attempt to force the madrileños to adopt French dress for public security reasons was the excuse for a riot (Motín de Esquilache), during which he did not display much personal courage. For a long time after, he remained at Aranjuez, leaving the government in the hands of his minister the Count of Aranda. Not all his reforms were of this formal kind.

The Count of Campomanes tried to show Charles that the true leaders of the revolt against Esquilache were the Jesuits. The wealth and power of the Jesuits were very great; and by the royal decree of 27 February 1767, known as the Pragmatic Penalty of 1767, the Jesuits were expelled from Spain, and all their possessions were confiscated. His quarrel with the Jesuits, and the memory of those with the Pope while he was King of Naples, turned him towards a general policy of restriction of what he saw as the overgrown power of the Church. The number of reputedly idle clergy, and more particularly of the monastic orders, was reduced, and the Spanish Inquisition, though not abolished, was rendered torpid.

In the meantime, much-antiquated legislation that tended to restrict trade and industry was abolished, and roads, canals, and drainage works were established. Many of his paternal ventures led to little more than the wasting of monies, or the creation of hotbeds of jobbery; on the whole, however, the country prospered. The result was largely due to the king who, even when ill-advised, did at least work steadily at his task of government.

Charles also sought to reform Spanish colonial policy, in order to make Spain's colonies more competitive with the plantations of the French Antilles (particularly the French colony of Saint-Domingue) and Portuguese Brazil. This resulted in the creation of the "Códigos Negros Españoles", or Spanish Black Codes. The Black Codes, which were partly based on the French Code Noir and 13th-century Castilian Siete Partidas, aimed to establish greater legal control over slaves in the Spanish colonies, in order to expand agricultural production. The first code was written for the city of Santo Domingo in 1768, while the second code was written for the recently acquired Spanish territory of Louisiana in 1769. The third code, which was named the "Código Negro Carolino" after Charles himself, divided the freed black and slave populations of Santo Domingo into strictly stratified socio-economic classes.[43]

In Spain, he continued with his work trying to improve the services and facilities of his people. He created the Luxury Porcelain factory under the name of Real Fábrica del Buen Retiro in 1760; Crystal followed by the Real Fábrica de Cristales de La Granja and then there was the Real Fábrica de Platería Martínez in 1778. During his reign, the areas of Asturias and Catalonia industrialized quickly and produced much revenue for the Spanish economy. He then turned to the foreign economy looking towards his colonies in the Americas. In particular, he looked at the finances of the Philippines and encouraged commerce with the United States, starting in 1778. He also carried out a number of public works; he had the Imperial Canal of Aragon constructed, as well a number of routes that led to the capital of Madrid, which is located in the center of Spain. Other cities were improved during his reign; Seville for example saw the introduction of many new structures such as hospitals and the Archivo General de Indias. In Madrid, he was nicknamed "el Mejor Alcalde de Madrid" (the Best Mayor of Madrid). Charles was responsible for granting the title "Royal University" to the University of Santo Tomás in Manila, which is the oldest in Asia.

In the capital, he also had the famous Puerta de Alcalá constructed along with the statue of Alcachofa fountain, and moved and redesigned the Real Jardín Botánico de Madrid. He had the future Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía built, as well as the Museo del Prado. At Aranjuez he added wings to the palace.

He created the Spanish Lottery and introduced Christmas cribs following Neapolitan models. During his reign, the movement to found "Economic Societies" (an early form of Chamber of Commerce) was born.

The Royal Palace of Madrid underwent many alterations under his rule. It was in his reign that the huge Comedor de gala (Gala Dining room) was built during the years of 1765–1770; the room took the place of the old apartments of Queen Maria Amalia. He died in the palace on 14 December 1788.

Ruler of the Spanish Empire

editCentralizing rule and raising revenue

editThe policies that centralized the Spanish state on the Iberian Peninsula were extended to its overseas territories, especially after the end of the Seven Years' War, when Havana and Manila were captured (1762–63) by the British. Charles's predecessors on the throne had begun reforming the relationship between the Iberian metropole Spanish American and Philippine possessions, to create a centralized and unified empire. The Seven Years' War had demonstrated to Charles that Spain's military was insufficient for a war with Britain. Military defense of the empire was a top priority, an expensive but necessary undertaking. With the 1763 peace treaty ending the Seven Years' War, Spain regained its ports of Havana, Cuba, and Manila, in the Philippines. Esquilache needed to find revenue to support the establishment of a standing military and fortification of ports. To raise funds, the sales tax alcabala was increased from 2% to 5%. To increase trade, Havana and other Caribbean ports were allowed to trade with other ports within the Spanish empire, not full trade, but comercio libre was freer trade. With the expansion, Spain hoped to undermine Britain's secret trade with Spanish America, and gain more revenue for the Spanish crown.[44]

Charles sent José de Gálvez as inspector general (visitor) to New Spain in 1765 to find ways to extract further revenue from its richest overseas possession and to observe conditions. The position gave sweeping powers to its holder, sometimes greater than that of the viceroy. Following his return to Spain in 1771, Gálvez became Minister of the Indies and proceeded with sweeping administrative changes, replacing the old system of governance with administrative districts (intendancies) and strengthening centralized crown control.[45]

Expulsion of the Jesuits, 1767

editCharles's Italian minister Esquilache was hated in Spain, seen as a foreigner, and responsible for policies that many Spaniards opposed. Bread riots in 1766, known as the Esquilache Riots, pinned the blame on the minister, but behind the uprising, the Society of Jesus was seen as the real culprit. After exiling Esquilache, Charles expelled the Jesuits from Spain and its empire in 1767. In Spanish America, the impact was significant, since the Jesuits were a wealthy and powerful religious order, owning lucrative haciendas that produced revenue funding its missions on the frontier and its educational institutions. For American-born Spaniards, at a stroke, the most wealthy and prestigious religious order that educated their sons and accepted a chosen few into their ranks were consigned to Italian exile. Jesuit properties, included thriving haciendas, were confiscated, the colleges educating their sons closed, and frontier missions were turned over to other religious orders. Politically, culturally, and economically the expulsion was a blow into the fabric of the empire.[46]

Bourbon Reforms

editThe government of Spain, in an effort to streamline the operation of its colonial empire, began introducing what became known as the Bourbon Reforms throughout South America.[47] In 1776, as part of these reforms, it created the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata by separating Upper Peru (modern Bolivia) and the territory that is now Argentina from the Viceroyalty of Peru. These territories included the economically important silver mines at Potosí, whose economic benefits began to flow to Buenos Aires in the east, instead of Cuzco and Lima to the west. The economic hardship this introduced to parts of the Altiplano combined with systemic oppression of Indian and mestizo underclasses created an environment in which a large-scale uprising could occur. In 1780 an indigenous insurrection of mostly Aymara and Quechua peoples took place against the colonial rulers of the Viceroyalty of Peru, led by Túpac Amaru II.[48] Túpac Amaru's uprising was simultaneous with the rebellion of Túpac Katari in colonial-era Upper Peru.[49]

Personal life

editCharles received the strict and structured education of a Spanish Infante by Giovanni Antonio de Medrano; he was very pious and was often in awe of his domineering mother, who according to many contemporaries, he resembled greatly. The Alvise Giovanni Mocenigo, Doge of Venice and Ambassador of Venice to Naples declared[10] that "...he received an education removed from all studies and all applications in order to be able to govern himself" (...tenne sempre un'educazione lontanissima da ogni studio e da ogni applicazione per diventare da sé stesso capace di governo).[50]

Giovanni Antonio de Medrano taught him geography, history and mathematics, as well as military art and architecture during his stay in the cities of Florence, Parma and Piacenza. He was also educated in printmaking (remaining an enthusiastic etcher), painting, and a wide range of physical activities, including a future favourite of his, hunting. Sir Horatio Mann, a British diplomat in Florence noted that he was greatly impressed at the fondness Charles had for the sport.

His physical appearance was dominated by the Bourbon nose that he had inherited from his father's side of the family. He was described as "a brown boy, who has a lean face with a bulging nose", and was known for his happy and exuberant character.[51]

Charles's mother Elisabeth Farnese sought potential brides for her son, when he was formally recognized as King of Naples and Sicily. It was impossible to get an Archduchess of Austria as a bride, so she looked to Poland, choosing Princess Maria Amalia of Saxony, a daughter of the newly elected Polish king Augustus III and his (ironically) Austrian wife Maria Josepha of Austria. Maria Josepha was a niece of Emperor Charles; the marriage was seen as the only alternative to an Austrian marriage. Maria Amalia was only 13 when she was informed of her proposed marriage. The marriage date was confirmed on 31 October 1737. Maria Amalia was married by proxy at Dresden in May 1738, with her brother Frederick Christian, Elector of Saxony representing Charles. This marriage was looked upon favorably by the Holy See and effectively ended its diplomatic disagreement with Charles. The couple met for the first time on 19 June 1738 at Portella, a village on the frontier of the kingdom near Fondi. At court, festivities lasted till 3 July. As part of the celebration, Charles created the Order of Saint Januarius—the most prestigious order of chivalry in the kingdom. He later had the Order of Charles III created in Spain on 19 September 1771.

The first crisis that Charles had to deal with as King of Spain was the death of his beloved wife Maria Amalia. She died unexpectedly at the Buen Retiro Palace on the eastern outskirts of Madrid, aged 35, on 27 September 1760. She was buried at the El Escorial in the royal crypt. Charles did not marry again. The example of his actions and works was not without effect on other Spanish nobles. In his domestic life, King Charles was regular, and was a considerate master, though he had a somewhat caustic tongue and took a rather cynical view of humanity. He was passionately fond of hunting. During his later years he had some trouble with his eldest son and daughter-in-law.

Charles was one of the largest slave owners in the Spanish Empire, owning 1,500 slaves in the Iberian Peninsula and a further 18,500 in Spain's American colonies. His slave ownership influenced the Spanish nobility, which started to emulate Charles by purchasing more slaves, to the point where by the 1780s 4% of Madrid's population was enslaved.[52] Charles was buried at the Pantheon of the Kings located at the Royal Monastery of El Escorial.

Relationship with Freemasonry

editThis section needs editing to comply with Wikipedia's Manual of Style#First-person pronouns. In particular, it has problems with the final paragraph of section (in sentences starting "But I also accept that..."), which appears to be either the editor talking in first person, plagiarism from a first person essay, a failed attempt at translating, &/or close paraphrasing from an uncited source.. (November 2023) |

Freemasonry arrived in Spain in 1726, by the year 1748, there were already 800 members in Cádiz, which was the door to Spanish America. During the reign of Carlos III, Freemasonry enjoyed wide liberties, where the most influential political leaders and social figures were distinguished members of the lodges (rumored to be the Rodríguez Campomanes, Esquilache, Wall, Azara, Miguel de la Nava, Pedro del Río, Jovellanos, Valle, Salazar, Olavide, Roda, the Duke of Alba, the Count Floridablanca and the Count of Aranda), managing to convince the king to limit the authority of the Spanish Inquisition (even being behind the Expulsion of the Jesuits), because the presence of Freemasonry was very influential in the Cortes of Carlos III and Carlos IV to encourage enlightened despotism, being almost omnipresent in the noble, literary and military aristocracies that surrounded him. It is not surprising that in the year 1751, when the Peruvian Inquisition had a case of accusation against a Frenchman, this revealed that in the city of Lima there were already at least 40 initiates in Freemasonry.[53][54][55][56][57][58] It is also mentioned that through Francisco Saavedra and the Gálvez brothers (Matías de Gálvez y Gallardo together with José de Gálvez y Gallardo), Freemasonry presented links with the government of the colonial territories in Hispanic America.[53]

However, despite this rosy legend of his relative tolerance, Charles III remained a devout Catholic who persecuted Freemasonry, first in the Kingdom of Naples (where in 1751 he had published an edict prohibiting Freemasonry as disturbing public tranquility and of violating the rights of Royal sovereignty) [59] and later in Spain, gaining the fame of being the most distinguished European monarch in repressing Freemasonry (according to the record of his letters) and being obedient to the anti-Masonic indications of the bull Providas Romanorum Pontificum of Pope Benedict XIV, which made impossible the development of an organized Freemasonry in Spain until the Napoleonic Era.[60][61] Authors such as José Antonio Ferrer Benimeli came to deny the Masonic influence during the Enlightenment in Spain.

However, authors such as Miguel Morayta (endorsing the thesis that Charles III was a Freemason) that his anti-Masonic attitudes were actually due to his concern "for his foreign dependence" (for the interests of the United Kingdom and to a lesser extent of his rivals in the French Enlightened), or that even his anti-Masonic policies were apparent, according to the Masonic oath of obedience and his vow of secrecy about his activities within Freemasonry (being, then, apparent and agreed persecutions).[62] Despite this, there is a consensus that the expansion of Freemasonry in the enlightened Spain of Charles III unquestionably developed, in the same way as it was developed in the other European countries (specifically in the royal and noble houses of Germany, France and England). According to the Freemason Carlos José Gutiérrez de los Ríos, he believes that the increase in the number of people joining Freemasonry, during the reign of Charles III, was the product of the naivety of many Spaniards: [63]

"The other initiates ignore it and enter in good faith for the attraction of fun and even flatter the recruits with mutual aid, they enjoy all the occasions of great ease to enter and find friends everywhere..."

Legacy

editThe rule of Charles III has been considered the "apogee of empire" and not sustained after his death.[64] Charles III ascended the throne of Spain with considerable experience in governance, and enacted significant reforms to revivify Spain's economy and strengthen its empire. Although there were European conflicts to contend with, he died in 1788, months before the eruption of the French Revolution in July 1789. Charles III did not equip his son and heir, Charles IV with skills or experience in governance. Charles IV continued a number of policies of his more distinguished father, but was forced to abdicate by his son Ferdinand VII of Spain and then imprisoned by Napoleon Bonaparte who invaded Spain in 1808.

The arms used by Charles while King of Spain were used until 1931 when his great-great-great grandson Alphonso XIII lost the crown, and the Second Spanish Republic was proclaimed (there was also a brief interruption from 1873 to 1875). Felipe VI of Spain, Spain's current monarch, is a direct male-line descendant of Charles the rey alcalde and a descendant by four of his great-great-grandparents. Felipe VI is also a descendant of Maria Theresa of Austria.

Charles III University of Madrid, established in 1989 and one of the world's top 300 universities,[65] is named after him.

-

Statue of Charles III in Madrid

-

Statue of Charles III in Madrid (Juan Adsuara), 1966

-

Charles III, statue du Real Jardín Botánico de Madrid

Family

editIssue

edit| Name | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Princess Maria Isabel Antonietta de Padua Francisca Januaria Francisca de Paula Juana Nepomucena Josefina Onesifora of Naples and Sicily | Palace of Portici, Portici, Modern Italy, 6 September 1740 | Naples, 2 November 1742 | died in childhood. |

| Princess Maria Josefa Antonietta of Naples and Sicily | Palace of Portici, 20 January 1742 | Naples, 1 April 1742 | died in childhood. |

| Princess María Isabel Ana of Naples and Sicily | Palace of Capodimonte, 30 April 1743 | Palace of Capodimonte, 5 March 1749 | died in childhood. |

| Princess María Josefa Carmela of Naples and Sicily | Gaeta, Italy 6 July 1744 | Madrid, 8 December 1801 | unmarried |

| Princess Maria Luisa of Naples and Sicily | Palace of Portici, 24 November 1745 | Imperial Palace of the Hofburg, Vienna, 15 May 1792 | married the future Leopold II, Holy Roman Emperor in 1765 and had issue. |

| Prince Felipe Antonio Genaro Pasquale Francesco de Paula of Naples and Sicily | Palace of Portici, 13 June 1747 | Palace of Portici, 19 September 1777 | Duke of Calabria; excluded from succession to the throne due to his imbecility |

| Prince Carlos Antonio Pascual Francisco Javier Juan Nepomuceno Jose Januario Serafin Diego of Naples and Sicily | Palace of Portici, 11 November 1748 | Palazzo Barberini, Rome, 19 January 1819 | future King Charles IV of Spain; married Princess Maria Luisa of Parma and had issue. |

| Princess Maria Teresa Antonieta Francisca Javier Francisca de Paula Serafina of Naples and Sicily | Royal Palace of Naples, 2 December 1749 | Palace of Portici, 2 May 1750 | died in childhood. |

| Prince Ferdinando Antonio Pasquale Giovanni Nepomuceno Serafino Gennaro Benedetto of Naples and Sicily | Naples, 12 January 1751 | Naples, 4 January 1825 | married twice; first married to Archduchess Maria Carolina of Austria and had issue; current line of the Two Sicilies descends from them; married secondly in a Morganatic marriage to Lucia Migliaccio of Floridia. Ferdinand saw the creation of the Two Sicilies in 1816. |

| Prince Gabriel Antonio Francisco Javier Juan Nepomuceno José Serafin Pascual Salvador of Naples and Sicily | Palace of Portici, 11 May 1752 | Casita del Infante, San Lorenzo de El Escorial, Spain, 23 November 1788 | married Infanta Mariana Vitória of Portugal, daughter of Maria I of Portugal; had three children, two of whom died young. |

| Princess Maria Ana of Naples and Sicily | Palace of Portici, 3 July 1754 | Palace of Capodimonte, 11 May 1755 | died in childhood. |

| Prince Antonio Pascual Francisco Javier Juan Nepomuceno Aniello Raimundo Sylvestre of Naples and Sicily | Caserta Palace, 31 December 1755 | 20 April 1817 | married his niece, Infanta Maria Amalia of Spain (1779–1798) in 1795 and had no issue. |

| Prince Francisco Javier Antonio Pascual Bernardo Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno Aniello Julian of Naples and Sicily | Caserta Palace, 15 February 1757 | Royal Palace of Aranjuez, Spain, 10 April 1771 | died 14 years old |

Ancestry

edit| Ancestors of Charles III of Spain[66] |

|---|

Heraldry

edit- Heraldry of Charles III of Spain

-

Coat of arms as Infante of Spain, Sovereign Duke of Parma, Piacenza and Guastalla, and Grand Prince and Heir of Tuscany

(1731–1735)[67] -

Coat of arms as Infante of Spain and King of Naples

(1736–1759)[67] -

Coat of arms as Infante of Spain and King of Sicily

(1736–1759) -

Coat of arms as King of Spain

(1761–1788)[68]

Further reading

edit- Acton, Sir Harold (1956). The Bourbons of Naples, 1734–1825. London: Methuen.

- Chávez, Thomas E. Spain and the Independence of the United States: An Intrinsic Gift, Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2002.

- Henderson, Nicholas. "Charles III of Spain: An Enlightened Despot," History Today, Nov 1968, Vol. 18 Issue 10, pp. 673-682 and Issue 11, pp. 760–768.

- Herr, Richard. "Flow and Ebb, 1700–1833" in Spain: A History, ed. Raymond Carr. Oxford: Oxford University Press 2000. ISBN 978-0-19-280236-1

- Herr, Richard. The Eighteenth Century Revolution in Spain. Princeton: Princeton University Press 1958.

- Lößlein, Horst. 2019. Royal Power in the Late Carolingian Age: Charles III the Simple and His Predecessors. Cologne: MAP.[permanent dead link]

- Lynch, John (1989). Bourbon Spain, 1700–1808. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-14576-1.

- Petrie, Sir Charles (1971). King Charles III of Spain: An Enlightened Despot. London: Constable. ISBN 0-09-457270-4.

- Stein, Stanley J. and Barbara H. Stein. Apogee of Empire: Spain and New Spain in the Age of Charles III, 1759–1789. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press 2003. ISBN 978-0801873393

- Thomas, Robin L. Architecture and Statecraft: Charles of Bourbon's Naples, 1734–1759 (Penn State University Press; 2013) 223 pages

Notes

editReferences

edit- ^ Stein, Stanley J. and Barbara H. Stein. Apogee of Empire: Spain and New Spain in the Age of Charles III, 1759–1789. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press 2003, p. 3.

- ^ Mörner, Magnus. "The expulsion of the Jesuits from Spain and Spanish America in 1767 in light of eighteenth-century regalism." The Americas 23.2 (1966): 156-164.

- ^ Nicholas Henderson, "Charles III of Spain: An Enlightened Despot," History Today, Nov 1968, Vol. 18 Issue 10, p673-682 and Issue 11, pp 760–768

- ^ Kuethe, Allan J. "Bourbon Reforms" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 1, pp. 399-401. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

- ^ Stanley G. Payne, History of Spain and Portugal (1973) 2:371

- ^ Lynch, John. Bourbon Spain, 1700-1808. Blackwell 1989, p. 2.

- ^ "Full text of "Unruly daughters; a romance of the house of Orléans"". Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- ^ a b Gleijeses, Don Carlos, Naples, Edizioni Agea, 1988, pp. 46–48.

- ^ (in Italian) Harold Acton, I Borboni di Napoli (1734–1825), Florence, Giunti, 1997, p. 18.

- ^ a b (in Italian) Vittorio Gleijeses, Don Carlos, Napoli, Edizioni Agea, 1988, p. 48.

- ^ a b Acton, Harold. I Borboni di Napoli (1734–1825) Florence, Giunti, 1997 p. 20

- ^ Gleijeses, Vittorio. Don Carlos Naples, Edizioni Agea, 1988. p. 49

- ^ Vittorio Gleijeses, Don Carlos, Naples, Edizioni Agea, 1988. p. 50-53

- ^ Harold Acton, I Borboni di Napoli (1734–1825), Florence, Giunti, 1997, p. 25

- ^ Vittorio Gleijeses, Don Carlos, Naples, Edizioni Agea, 1988. p. 59

- ^ Vittorio Gleijeses, Don Carlos, Naples, Edizioni Agea, 1988. p. 60

- ^ Vittorio Gleijeses, Don Carlos, Naples, Edizioni Agea, 1988. p. 61-62

- ^ Vittorio Gleijeses, Don Carlos, Naples, Edizioni Agea, 1988, p. 63-64.

- ^ a b Vittorio Gleijeses, Don Carlos, Naples, Edizioni Agea, 1988, pp. 65–66

- ^ Giovanni Drei, Giuseppina Allegri Tassoni (a cura di) I Farnese. Grandezza e decadenza di una dinastia Italiana, Rome, La Libreria Dello Stato, 1954.

- ^ Rex Neapolis before his coronation on 3 July 1735 at Palermo.

- ^ Liste des décrets sur le site du ministère de la Culture espagnole.

- ^ Acton, Harold. I Borboni di Napoli (1734–1825), Florence, Giunti, 1997

- ^ Luigi del Pozzo, Cronaca Civile e Militare delle Due Sicilie sotto la dinastia borbonica dall'anno 1734 in poi, Naples, Stamperia Reale, 1857.

- ^ Giuseppe Coniglio, I Borboni di Napoli, Milan, Corbaccio, 1999.

- ^ Gaetano Falzone, Il Regno di Carlo di Borbone in Sicilia. 1734–1759, Bologne, Pàtron Editore, 1964.

- ^ Stein and Stein, Apogee of Empire, pp. 4-5.

- ^ The Academy of Real Navy 10 December 1735, was the first institution to be established by Charles III for cadets, followed 18 November 1787 by the Royal Military Academy (later Military School of Naples): Buonomo, Giampiero (2013). "Goliardia a Pizzofalcone tra il 1841 ed il 1844". L'Ago e Il Filo Edizione Online (in Italian).

- ^ (in Italian) Quei Lumi accesi nel Mezzogiorno.

- ^ Francesco Renda, Storia della Sicilia Dalle origini ai giorni nostri vol. II, Palerme, Sellerio editore, 2003.

- ^ Jo Marchant (2018). "Buried by the Ash of Vesuvius, These Scrolls Are Being Read for the First Time in Millennia". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- ^ Franco Valsecchi, Il riformismo borbonico in Italia, Rome, Bonacci, 1990

- ^ Burkholder, Suzanne Hiles. "Charles III of Spain" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture vol. 2, p. 81-82. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996

- ^ Herr, Richard. "Flow and Ebb, 1700-1833" in Spain: A History. Raymond Carr, ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press 2000, p. 176.

- ^ Kuethe, "Bourbon Reforms", p 400.

- ^ Lynch, p. 319

- ^ Letter from Tadeo de Medrano y Acedo to the 12th Duke of Béjar https://pares.mcu.es/ParesBusquedas20/catalogo/description/3921330

- ^ Fegley, Randall (1989). Equatorial Guinea: An African Tragedy, p. 5. Peter Lang, New York. ISBN 0820409774

- ^ Weber, David J. The Spanish Frontier in North America. New Haven: Yale University Press 1992

- ^ Moorhead, Max L. (1991). The Presidio: Bastion of the Spanish Borderlands. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma. ISBN 978-0-8061-2317-2.

- ^ Lynch, pp. 319–321

- ^ Burkholder, Suzanne Hiles. "Charles III of Spain" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 1, pp. 81-82. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

- ^ Obregón, Liliana (January 1999). "Black Codes in Latin America". Africana: Eneyhpedia of the African and African. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ^ Kuethe, "Bourbon Reforms", p. 400

- ^ Kent, Jacquelyn Briggs. "Intendancy System" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 3, 286-87. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

- ^ D.A. Brading, The First America: The Spanish Monarchy, Creole Patriots, and the Liberal State, 1492-1867. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1991, pp. 453-58.

- ^ Robins, Nicholas A.: Genocide and millennialism in Upper Peru: the Great Rebellion of 1780–1782

- ^ Serulnikov, Sergio (2013). Revolution in the Andes: The Age of Túpac Amaru. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822354833.

- ^ Robins, Nicholas A.; Jones, Adam (2009). Genocides by the Oppressed: Subaltern Genocide in Theory and Practice. Indiana University Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0-253-22077-6. Archived from the original on 15 October 2015.

- ^ Il di lui talento è naturale, e non-stato coltivato da maestri, sendo stato allevato all'uso di Spagna, ove i ministri non-amano di vedere i loro sovrani intesi di molte cose, per poter indi più facilmente governare a loro talento. Poche sono le notizie delle corti straniere, delle leggi, de' Regni, delle storie de' secoli andati, e dell'arte militare, e posso con verità assicurare la MV non-averlo per il più sentito parlar d'altro in occasione del pranzo, che dell'età degli astanti, di caccia, delle qualità de' suoi cani, della bontà ed insipidezza de' cibi, e della mutazione de' venti indicanti pioggia o serenità. Michelangelo Schipa, Il regno di Napoli al tempo di Carlo di Borbone, Napoli, Stabilimento tipografico Luigi Pierro e figlio, 1904, p. 72.

- ^ (in Italian) Michelangelo Schipa, Il regno di Napoli al tempo di Carlo di Borbone, Naples, Stabilimento tipografico Luigi Pierro e figlio, 1904, p. 74.

- ^ Kassam, Ashifa (2 April 2024). "'Hidden in plain sight': the European city tours of slavery and colonialism". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 13 September 2024.

- ^ a b Pérez-Bustamante, Rogelio (2017). "Miguel Cayetano Soler en el espíritu del reformismo ilustrado y masónico". Memòries de la Reial Acadèmia Mallorquina d'Estudis Genealògics, Heràldics i Històrics (27): 145–169. ISSN 1885-8600. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ Benimeli, José Antonio Ferrer (1973). Masonería e Inquisición en Latinoamérica durante el siglo XVIII (in Spanish). Universidad Católica/Andrés Bello, Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ Ferrer Benimeli, José Antonio (1976). Masonería, Iglesia e Ilustración: un conflicto ideológico-político-religioso. Fundación Universitaria Española. ISBN 9788473920872. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ Benimeli, José Antonio Ferrer (1968). La masonería después del Concilio (in Spanish). Editorial AHR. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ Berteloot, Joseph (1947). La franc-maçonnerie et l'église catholique. Collection hommes et cité. Éd. du Monde Nouveau. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ "Historia de las sociedades secretas, antiguas y modernas en España y especialmente de la Francmasonería - Wikisource". es.wikisource.org (in Spanish). Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ Benimeli, José Antonio Ferrer (1 January 1974). La masonería espãnola en el siglo XVIII (in Spanish). Siglo XXI de España Editores. ISBN 9788432301407. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ Barbadillo, Pedro Fernández (20 February 2017). "Carlos III, un rey que nos vino ya enseñado". Libertad Digital - Cultura (in European Spanish). Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ "LA MASONERÍA EN ESPAÑA (1728-1979)". www2.uned.es. Archived from the original on 23 March 2023. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ Morayta, Miguel (1915). Masoneria española: páginas de su historia (in Spanish). Establecimiento Tipográfico. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ Cervantes, Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de. "Vida de Carlos III. Tomo I". Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes (in Spanish). Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ Stein, Stanley and Barbara H. Stein. Apogee of Empire: Spain and New Spain in the Age of Charles III, 1759–1789. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press 2003. ISBN 978-0801873393

- ^ "Universidad Carlos III de Madrid (UC3M)". Top Universities. 13 December 2012. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ^ Genealogie ascendante jusqu'au quatrieme degre inclusivement de tous les Rois et Princes de maisons souveraines de l'Europe actuellement vivans [Genealogy up to the fourth degree inclusive of all the Kings and Princes of sovereign houses of Europe currently living] (in French). Bourdeaux: Frederic Guillaume Birnstiel. 1768. p. 8.

- ^ a b Menéndez-Pidal De Navascués, Faustino; (1999)El escudo; Menéndez Pidal y Navascués, Faustino; O´Donnell, Hugo; Lolo, Begoña. Símbolos de España. Madrid: Centro de Estudios Políticos y Constitucionales. ISBN 84-259-1074-9, p. 208.209

- ^ "Carlos III, Rey de España (1716-1788)". Ex-Libris Database (in Spanish). Royal Library of Spain. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

External links

edit- Historiaantiqua. Carlos III; (Spanish) (2008)

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.