This article may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (December 2011) |

The House of Keglević or Keglevich is a Croatian noble family originally from Northern Dalmatia, whose members were prominent public citizens and military officers. As experienced warriors, they actively participated in the Croatian–Ottoman and Ottoman–Hungarian wars, as well were patrons of the arts and holders of the rights of patronage over churches and parishes.[2][3]

| Keglević | |

|---|---|

| Croatian-Hungarian noble family | |

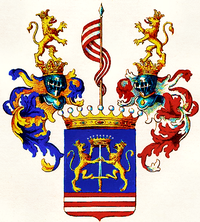

Coat of arms granted to the Keglevich family along with the hereditary title of Count in 1687 by Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor | |

| Parent house | Prkalj (Perkal)[1] |

| Country |

|

| Founded | c. 1322[1] |

| Founder | Kegalj Prkalj[1] |

| Final ruler | Oskar Keglević[1] |

| Titles | Baron, Count, Graf, , Vicebanus, Ban |

| Dissolution | 1918 (Croatian branch) extant (Hungaro-Brazilian branch)[1] |

| Cadet branches | Porički, Gradački, Bužimski[1] |

History

editThe first known ancestor was Peter de genere[4] Percal, a castle lord, who was mentioned in a supreme court verdict by Mladen II Šubić in Northern Dalmatia (Pozrmanje[5]) about the right to judge a case concerning grazing rights in a village in the year 1322.[1] Peter was mentioned as a son of Budislav de genere Percal and as a brother of Jakob de genere Percal, and his family was explicitly called nostra nobilissima familia (our most noble family).[6][7][8]

Stephanos Keglevich de Porychane was mentioned in 1386 as "Stephanus Maurus the procurator of the church of Saint Saviour (St. Salvator) in Šibenik", in 1413 he inherited the "terra Porychan" (beneath their Kegaljgrad[5]) as "Stephanus Maurus" and in 1435 he was mentioned as "Stephanos Keglevich de Porychane the son of Kegal de genere Percal".[6][7] Since 1412 the family is mentioned only under the patronymic of Kegal/Kegalj - Keglević.[1] The church of the Holy Saviour (Sveti Spas, St. Salvator) in Šibenik was built until 1390, belonged to a Benedictine convent and was since 1807 until 1810 the Orthodox parish church, but it is not the present church of Holy Saviour in Šibenik, because this was built in 1778 as Christ's Ascension Church and later changed the name. It is since 1810 the Assumption of Mary Church.[9] The Procurators work closely with architects and engineers to ensure the building of the church. Pope Boniface IX founded in 1391 the monastery of Saint Clara in Šibenik and ordered to build another church for it, because, as he wrote, there were some wives at the newly built church of St. Salvator, but they were obviously not sitting on rules.[10]

Since 1487 their estates expanded into županijas of Knin, Nebljuh, Gacka, and Lika, as well city of Bužim in 1495. Since the Ottoman intrusion family and its branches migrated to županija of Zagreb, Varaždin, region of Slavonia, and the Kingdom of Hungary (where was founded in the 17th century the Hungarian branch of the family). In the 16th century they had so many estates in Međimurje that were obligated by Croatian Sabor in 1542 to return the region to Ferdinand I, Holy Roman Emperor, but Ferdinand I returned the most of it five years later. Because of it, had half a century conflict with the Székely von Kövend noble family for Krapina and Kostel estates.[5]

Gloss

editThis surname became a victim of the Austrian Nazi propaganda.[11][12][13][14][clarification needed]

Properties

edit-

Bužim fortress, owned by Keglevich family from 1495 until 1576

-

Ruins of Kalnik fortress, Kalnik mountain, Croatia

-

Ruins of fortress Kegaljgrad, Mokro Polje, Croatia

-

Čakovec fortress, Croatia, owned by Keglevich family from 1540-1546

-

Keglevich palace in Bratislava, Slovakia

-

Keglevich castle in Pétervására, Hungary

-

Keglevich palace in Sveti Križ Začretje, Croatia

-

Keglevich castle in Csécsei, Nógrád County, Hungary

-

New castle Krapina, Croatia

-

Opeka castle, built by Keglevich family in 1674

-

Keglevich house, Nagykáta, Hungary

Coats of arms

edit| Coat of arms of the House of Keglević de Porychane until 1490. de gueules à deux fasces d'argent. Gules, two bars argent. with a lion holding a sun,[15] see also: Lion and Sun |

| Coat of arms of the House of Keglević de Buzin since 1494.[16] |

| Coat of arms of the House of Keglević de Buzin since 1687.[17] |

Notable members

edit- Petar Keglević II (ca. 1485 – ca. 1555) was captain and later ban of Jajce, from 1521 to 1522. In 1526, some months before the battle of Mohács, he got the jus gladii. However, he did not take part in the battle of Mohács (he arrived too late). From 1533 to 1537 he was the royal commissary for Croatia and Slavonia as attorney general. From 1537 to 1542 he was the Ban of Croatia and Slavonia.

- Juraj/György Keglević III (unknown – 1622) was Commander-in-chief, General, Vice-Ban of Croatia, Slavonia and Dalmatia (14 April 1598 – 21 October 1599) and since 1602 Baron in Transylvania.[18] Matthias II imprisoned him, but soon left him free again. At that time was the Principality of Transylvania a fully autonomous, but only semi-independent state under the nominal suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire, where it was the time of the Sultanate of Women.

- Petar Keglević V (1609–1665) was the adjoining Colonel at Nagykanizsa, when he became Vice-General in 1649.[19]

- Petar Keglević VII (1660–1724) was the Commander-in-chief, General, Vice-Ban of Croatia, Slavonia and Dalmatia and since 1687 Count in Hungary.

- Nikola Keglević was since 1687 Count of Torna County in Kingdom of Hungary, now Slovakia.[20][21] Nicolaus Keglevich started Keglevich dynasty in Kingdom of Hungary.

- Sigismund Keglević was the Titular bishop of Mrkan between 1764 and 1805.[22]

- Aleksandar Keglević was in 1770 or 1771 rector of the University of Trnava,[23] it began the moving of the University into the Royal Palace Buda Castle with the permission of Maria Theresa of Austria, it was moved in 1777 to Buda and finally to Pest in 1784.

- Tereza Keglević, the Countess of Bratislava in Kingdom of Hungary (now Slovakia). She bought a Keglevich Palace from Joseph Duchoň in 1745 on 15 February, for 7 000 crowns.[24]

- Josip I Keglević was very liked by Emperor Peter III of Russia, who called him "Sir brother".[25] His father, also called Josip, had been ambassador to Russia. He was curator of the tenant of the court theatre in Vienna (1773–1776) of Johann count Kohary, who had come into financial problems.[26] He was one of the two crown guards of the Holy Crown of Hungary (1772-1795).[27] He was the magister agazonum (Marshal) between 1794 and 1798.[28] and also the Count of Torna County.[20]

- Josip II Keglević was the secretary of the Vice-council, member of the Diet of Hungary ("Hungarian Parliament") and also, like his father, the protector of the Royal Crown. He had lived in Bratislava, in Keglevich Palace.

- Franjo Keglević was the husband of the sister of the director of the court theater Hoftheater Burgtheater in Vienna Wenzel count Sporck and was chairman of the committee for financing the court theater Hoftheater Burgtheater in Vienna between 1773 and 1776.[29] In 1809, he or another Franciscus Keglevich promised to the Emperor Francis a particular exchange rate between gold in natura and gold coins or silver coins, because he had got gold in natura 2 years before the bankruptcy of the state of Austria in 1811.[30][31]

- Charles Keglevich became in 1773 director of the city theater Theater am Kärntnertor in Vienna.[32]

Keglevich, today it is not known whether Alexander, Francis or Charles has financed a variety of expenses of Maria Theresa of Austria, which supposedly should have been returned by the theater fund.[33]

- Ana Luiza Barbara Keglević (1780-1813), also called Babette was the daughter of Karlo Keglević and Catherine Zichy.[21] She was a student of Ludwig van Beethoven in Vienna and Bratislava,[34] who dedicated to her his Piano Sonata No. 4 in E-flat major op. 7 and his Piano Concerto No. 1 in C major op. 15.[35][36]

- Katarina Patačić, born Keglević published a 'Croatian Songbook' in 1781 that featured lyric and melodramatic pieces with love songs to her husband and a fable of Aesop written in the Croatian Kaj dialect. She wrote for the court audience, but she did not use common versification. A number of minor poets and other writers continued to imitate her style of writing.[37]

- Nera Keglević became a fictional character in the most famous cycle of 7 novels Grička vještica (The Witch of Grič) by Marija Jurić Zagorka. The novels start with Nera's 17th birthday in 1775. She is fighting against believing in witches and witchcraft in this novels. But the problem in this novels is that the towns judge Krajačić is accusing Nera to be a witch for revenge. Finally she became the last accused witch in Legal history in Croatia.

- Balthasar Melchior Gaspar Keglovich became a fictional character in the poem Keglovichiana by Miroslav Krleža who in another of his poems claimed that Josip Broz Tito was an illegitimate child of Franjo Keglević.[38][39] Franjo J Keglević, son of Franjo Keglević who was a wholesaler of pigs in Koprivnica in 1905, where in 1837 Bartol Keglević was a butcher, published the journal "Slobodni glas" ("the free vote"), whose first issue came out in Ogulin on 18 September 1909, where in 1868 Škender Keglević, who was a merchant, was a subscriber of the journal "Dragoljub" ("precious love") and where Tito soon found himself imprisoned in a 15th-century Frankopan tower, the jail of the county court of Ogulin.[40][41][42][43] Franjo J Keglević became a fictional character as a pilot of the Hungarian Red Army with his private plane of the Imperial Army, a member of the Central Executive Committee of the Soviet Hungary and a Communist in a story in the Russian journal "Наши достижения" ("our achievements") by Maksim Gorky, who in the same year came into house arrest.[44]

- Johannes Keglević, brother of Stjepan Bernhard Keglević, became Colonel in 1796. He distinguished himself in the battle of Mainz in 1795 with his private Hessian (soldiers).[27] He was awarded the Military Order of Maria Theresa in 1798 "for by his own initiative undertaken and successfully a campaign significantly affecting feats of arms, which an officer of honor would may have omitted without blame." He died at Offenburg in 1799.[45]

- Stjepan Bernhard Keglević, brother of Johann Keglevich, became Major General in 1793 and was killed in the winter of 1793/1794 in the battle of Uttenhoffen with some of his private Serbian soldiers as they were attacked by surprise in their hidden winter camp in a wood near Uttenhoffen.[27][46][47]

- Julije Keglević was due to his letters an interesting personality. In 1784 he wrote to Joseph II a letter in which he wrote: "I write German, not because of the instruction, your grace, but because I have to do with a German citizen." It took time until this "German citizen" Joseph II visited him as a private person. Julije Keglević, local patron, has denied any obligation towards the Church, because the bishop did not respect the patron's rights regarding the promotion of the new parish priest. A young priest has concluded that there was no point to repair this church and in 1794 he wrote a letter addressed to the county with the suggestion that a new parish church had to be built. This conflict whether the new church should be built or not lasted for two years and the County remained neutral during this time.

- Karl Keglević composed at the ages of 24 and 25 also a coronation march for pianoforte for 4 hands in C major and a waltz with trio and coda forte, which were published by Anton Diabelli and Company in 1830 and 1831 in Vienna.

- Ivan Keglević (magister pincernarum (Master of the Cup-bearers), knight of the papal Order of Christ; 1839–1847), who died in 1856, was in 1812 at an age of 26 years one of the co-founder of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde (Society of Music Friends) in Vienna known as the Musikverein (Music Association) and one of the permanent members of its committee.[48] In his palace in Vienna, today Palais Schönburg, lived the Turkish ambassador Ahmed Paşa and Miloš Obrenović I, Prince of Serbia when this visited Vienna.[49]

- Ivan Keglović was the magister curiae regis (Curia Regia) between 1847 and 1860. In the conclusion of the so-called April Laws is written: "given by Banus Count Keglevich of Buzin."[50]

- Gábor Keglević was the magister tavernicorum regalium (Treasurer (Kingdom of Hungary)) between 1842 and 1848. He and some others founded in 1845 a financing association to finance the Hungarian industry and to protect the loan repayments. The share capital amounted 100'000 forints and the establishing of the common shares were worth 960'000 forints at the beginning of this association in 1845.[51]

- Stjepan Keglević became the youngest member of the Hungarian Parliament in 1861 at an age of 21. In 1867 he laid back his parliamentary mandate on the same day as Gyula Andrássy became Prime Minister, and he began to take care about the economy of his goods. In 1873 he went bankrupt at the Vienna stock market crash (see Panic of 1873), he was in debt to his wife, his children and his relatives, who had taken over the third-largest bank in Hungary, the bankruptcy estate was auctioned until 1890. He started in 1873 from zero. He gave out lottery - loans again as before in 1847, which were covered with all his assets, which, however, was zero at this time, what, may be, not everyone knew. He became very successful. He was the Intendant of the National Theater in Budapest between 1886 and 1887. He became again a member of the Parliament. In 1895 he proved with arguments the permission of the state to reform the marriage law, that also Christians compels to the form of the civil marriage at the registry office, because it was in his opinion not a question of the freedom of conscience. He inferred from this a necessity to reform the Upper House of the Parliament. In 1905 he was killed in a duel by another member of the Parliament.[52][53][54][55][56][57]

- Nevenka Dörr (ehem. Jurisa)

- Barbara "Babsi" Dörr

- Andrea Bauer (ehem. Dörr)

- Karen Tallian member of the Indiana Senate, USA. (Paul Tallian had the largest holdings in the puszta after 1856, his mother was born Keglevich.)

- Maria-Jenke (1921-1983), daughter of Count Stephan Keglevic de Buzin, and second wife of CrownPrince Albrecht of Bavaria (1905-1996)

See also

edit- List of titled noble families in the Kingdom of Hungary

- Keglevich (Italian brand of vodka)

References

editNotes

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h Majnarić & Katušić 2009.

- ^ Enciklopedija, opća i nacionalna u 20 knjiga, Antun Vujić, Pro Leksis (etc.), Zagreb 2005.

- ^ Građa za istoriju vojne granice u XVIII veku, Slavko Gavrilović, Radovan Samardžić, Srpska akademija nauka i umetnosti, Beograd 1989.

- ^ From the 1220s, several individuals commenced to refer to their clan in the official documents by using the expression de genere ("from the kindred of") following their name which suggests that the relevance even of distant kinship started to increase. See Fügedi, Erik (1986). Ispánok, bárók, kiskirályok ('Counts, Barons and Petty Kings'). Budapest: Magvető Könyvkiadó, p. 79. ISBN 963-14-0582-6

- ^ a b c Croatian Encyclopaedia 2020.

- ^ a b Starine, svezak 44, stranica 250, Jugoslavenska akademija znanosti i umjetnosti, Hrvatska akademija znanosti i umjetnosti. Razred za društvene znanosti, Akademija, 1952.

- ^ a b Zsigmondkori oklevéltár: 1413-1414, Volume 25 of Publicationes archivi nationalis Hungarici / 2, page 287, Magyar Országos Levéltár (Budapest), Magyar Országos Levéltár kiadványai: Forráskiadványok Volume 4 of Zsigmondkori oklevéltár, Elemér Mályusz, Iván Borsa, Akadémiai Kiadó, 1994, ISBN 978-963-05-7026-8

- ^ Acta Keglevichiana annorum 1322 - 1527: najstarije isprave porodice Keglevića do boja na Muhačkom polju, Vjekoslav Klaić, 1917.

- ^ Treasures of Yugoslavia: an encyclopedic touring guide, page 233, Nebojša Tomašević, translated by Madge Tomašević and Karin Radovanović, Yugoslaviapublic 1982.

- ^ Pope Boniface IX about the wives in Šibenik

- ^ Hans Hinkel (1939). Judenviertel Europas | Die Juden zwischen Ostsee und Schwarzen Meer [Jew Quarter of Europe] (in German). Volk und Reich Verlag.

- ^ Life. Vol. 32. April 1952. p. 21.

- ^ Österreichische Geschichte (in German). Vol. 10. Roman Sandgruber Ueberreuter Verlag. 1995.

- ^ "Arisierungen," beschlagnahmte Vermögen, Rückstellungen und Entschädigungen in Oberösterreich (in German). Daniela Ellmauer, Michael John, Regina Thumser. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag. 2004.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ cit: Hunc iste, postquam Dalmatae pacto hoc a Hungaria separati se non tulissent, revocatum contra Emericum armis vindicavit, ac Chelmensi Ducatu, ad mare sito, parteque Macedoniae auxit. AD 1199. Luc. lib. IV. cap. III. Diplomata Belae IV. AD 1269.

- ^ cit: Leopold I, King of Hungary in 1687 in Bratislava: "Counts in Hungary", "Invictus est.", Der Adel von Kroatien und Slawonien, Nürnberg 1899, Nachdruck Neustadt and d. Aisch, Bauer & Raspe, 1986, ISBN 3-87947-035-9

- ^ Deutsche Grafenhäuser der Gegenwart: in heraldischer, historischer und genealogischer Beziehung. A - Z, Band 3, Ernst Heinrich Kneschke, Weigel, 1854.

- ^ Nikolaus von Preradovich

- ^ Petar Keglević V

- ^ a b Frederik Federmayer: Rody starého Prešporka. Bratislava/Pressburg/Pozsony 2003

- ^ a b Ján Lacika: Bratislava a okolie - turistický sprievodca. Vydavateľstvo Príroda, s.r.o., Bratislava 2004

- ^ T.E.: Keglevich Zsigmond, buzini, gr. (MKL)

- ^ Ungarische Revue, Volume 11, S.53, Magyar Tudományos Akadémia, Franklin-Verein, 1891.

- ^ Jana Oršulová: Heraldické pamiatky Bratislavy. Albert Marenčin Vydavateľstvo PT, Bratislava 2007

- ^ 1747, 1752 bis 1763, Johann Karl Christian Heinrich von Zinzendorf, Maria Breunlich, Böhlau Verlag Wien, 1998.

- ^ Théâtre, nation & société en Allemagne au XVIIIe siècle, Roland Krebs, Jean Marie Valentin, Presses universitaires de Nancy, 1990.

- ^ a b c Europäische Aufklärung zwischen Wien und Triest: die Tagebücher des Gouverneurs Karl Graf von Zinzendorf, 1776-1782, S. 300, Karl Zinzendorf (Graf von), Grete Klingenstein, Eva Faber, Antonio Trampus, Böhlau Verlag, Wien 2009.

- ^ WWW-Personendatenbank des höheren Adels in Europa, Herbert Stoyan

- ^ Alt und Neu Wien: Geschichte der österreichischen Kaiserstadt, Band 2, von Karl Eduard Schimmer, Horitz Bermann, Wien 1904, Seite 215

- ^ Historia critica regum Hungariæ. [42 vols. in 41 pt. Vols. 7 and 21 were apparently omitted from the numeration in this edition]. page 438, István Katona, Buda 1817.

- ^ The Life of Beethoven, page 110, David Wyn Jones, Cambridge University Press, 1998, ISBN 978-0521568784

- ^ Katalog der Portrait-Sammlung der k.u.k. General-Intendanz der k.k. Hoftheater: zugleich ein biographisches Hilfsbuch auf dem Gebiet von Theater und Musik, Burgtheater, Wien 1892, A. W. Künast

- ^ Briefe an ihre Kinder und Freunde; Verfasser/in: Maria Theresa, Empress of Austria; Alfred Ritter von Arneth, Verlag: Braumüller, Wien 1881.

- ^ "BBC - Radio 3 - Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 4 in e flat, Op. 7".

- ^ Zweite Beethoveniana: Nachgelassene Aufsätze, Seite 512, Bibliothek der deutschen Literatur, Gustav Nottebohm, Verlag Peters, 1887.

- ^ Ludwig van Beethoven's Leben, Alexander Wheelock Thayer, Hermann Deiters, Hugo Riemann, Verlag: Berlin, W. Weber, 1901-11.

- ^ Trois ecritures, trois langues: pierres gravées, manuscrits anciens et publications croates à travers les siècles, Josip Stipanov, Srećko Lipovčan, Zlatko Rebernjak, Bibliothèque royale de Belgique, Erasmus naklada, 2004.

- ^ Franjo Keglević [dead link]

- ^ S Krležom iz dana u dan: Trubač u pustinji duha, Enes Čengić, Miroslav Krleža, Globus, 1985.

- ^ Life, Volume 32, Nr. 17, 28 April 1952, page 62, ISSN 0024-3019

- ^ Sabrana djela, svezak 18., stranica 227., Dr. Antun Radić, Stjepan Radić, Seljačka sloga, Zagreb 1939.

- ^ Dragoljub: zabavan i poučan tjednik, svezak 2., stranica 816., godina 1868.

- ^ O trgovini u staroj Koprivnici, stranica 62. Hrvoje Petrić, Radovi Zavoda za znanstveni rad, HAZU Varaždin, Original Scientific Paper, 2009.

- ^ Наши достижения, Maxim Gorky, p. 66, Журнально-газетное объединение, 1934.

- ^ Die reiter-regimenter der k.k.österreichischen armee, Andreas Thürheim (Graf.), F.B. Geitler, 1862.

- ^ map from 1795

- ^ The crown of Opatija

- ^ Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des österreichischen Kaiserthumes, Verfasser/in: Austria, Verlag: Wien: Aus der k. k. Hof- und Staats-Aerarial-Druckerey, Ausgabe/Format: Zeitschrift: Nationale Regierungsveröffentlichung

- ^ Augsburger Postzeitung, Haas & Grabherr, 13.März 1836.

- ^ Stenographische Protokolle über die Sitzungen des Hauses der Abgeordneten des österreichischen Reichsrates, Ausgaben 318-329, Seite 29187, Austria, Reichsrat, Abgeordnetenhaus, published 1905.

- ^ Jahrbücher für slawische Literatur, Kunst und Wissenschaft, Band 3, Seite 72, Dr. J. P. Jordan, Universität Leipzig, 1845, Zentralantiquariat der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik.

- ^ Der ungarische Reichstag, 1861, Hungary országgyülés, 1861.

- ^ Neue Würzburger Zeitung / Morgenblatt, 1867.

- ^ Studia musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, Bände 1-2, Magyar Tudományos Akadémia, Acad., 1961.

- ^ Schulthess' europäischer Geschichtskalender, 1895.

- ^ Sendbote des göttlichen Herzens Jesu, Band 33, Apostleship of Prayer (Organization), Franziskaner-Vätern, 1906.

- ^ Entwicklung und Ungleichheit: Österreich im 19. Jahrhundert, S. 142, Michael Pammer, Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 978-3-515-08064-4

Sources

edit- Croatian Encyclopaedia (2020), Keglevići

- Majnarić, Ivan; Katušić, Maja (2009), "Keglević", Croatian Biographical Lexicon (HBL) (in Croatian), Miroslav Krleža Lexicographical Institute