This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (December 2016) |

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in German. (February 2011) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

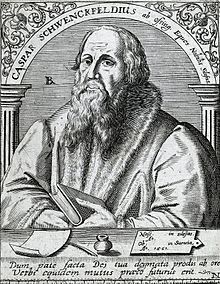

Caspar (or Kaspar) Schwen(c)kfeld von Ossig (ⓘ) (1489 or 1490 – 10 December 1561) was a German theologian, writer, physician, naturalist, and preacher who became a Protestant Reformer and spiritualist. He was one of the earliest promoters of the Protestant Reformation in Silesia.

Schwenckfeld came to Reformation principles through Thomas Müntzer and Andreas Karlstadt. However, he developed his own principles and fell out with Martin Luther over the eucharistic controversy (1524). He had his own views on the sacraments, known as the Heavenly Flesh doctrine, that were developed in close association with Valentin Crautwald, his humanist colleague. His followers became a new sect, which was outlawed in Germany. Its ideas were influenced by Anabaptism, Pietism in Europe, and Puritanism in England.

Many of his followers were persecuted in Europe and thus forced to either convert or flee. Because of this, there are Schwenkfelder Church congregations in the United States, which was then the Thirteen Colonies of British America until American independence was achieved following the American Revolutionary War.

Early life and education

editSchwenckfeld was born in Ossig near Liegnitz, Silesia now Osiek, near Legnica, Poland, to noble parents in 1489.[1] Between 1505 and 1507, he was a student in Cologne. In 1507, he enrolled at the University of Frankfurt on the Oder. Between 1511 and 1523, Schwenckfeld served the Duchy of Liegnitz as an adviser to Duke Charles I (1511–1515), Duke George I (1515–1518), and Duke Frederick II (1518–1523).

Career

editIn 1518 or 1519, Schwenckfeld experienced an awakening that he called a "visitation of God". Martin Luther's writings had a deep influence on Schwenckfeld, and he embraced the "Lutheran" Reformation and became a student of the scriptures. In 1521, Schwenckfeld began to preach the gospel, and in 1522 won Duke Friedrich II over to Protestantism. He organized a Brotherhood of his converts for the purpose of study and prayer in 1523. In 1525, he rejected Luther's idea of real presence and came to a spiritual interpretation of the Lord's Supper, which was subsequently rejected by Luther.

Schwenckfeld began to teach that the true believer ate the spiritual body of Christ. He pushed for reformation wherever he went, but also criticized reformers that he thought went to extremes. He emphasized that for one to be a true Christian, one must not change only outwardly but inwardly. Because of the communion and other controversies, Schwenckfeld broke with Luther and followed what some describe as a "middle way". Because of his break from Luther and the Magisterial Reformation, scholars typically categorize Schwenckfeld as a member of the Radical Reformation. He voluntarily exiled himself from Silesia in 1529 in order to relieve pressure on and embarrassment of his duke. He lived in Strasbourg from 1529 to 1534, and then in Swabia.

Teachings

editSome of the teachings of Schwenckfeld included opposition to war, secret societies, and oath-taking, that the government had no right to command one's conscience, that regeneration is by grace through inner work of the Spirit, that believers feed on Christ spiritually, and that believers must give evidence of regeneration. He rejected infant baptism, outward church forms, and "denominations". His views on the Eucharist prompted Luther to publish several sermons on the subject in his 1526 The Sacrament of the Body and Blood of Christ—Against the Fanatics.

Publications

editIn 1540 Luther expelled Schwenckfeld from Silesia. In 1541, Schwenckfeld published the Great Confession on the Glory of Christ. Many considered the writing to be heretical. He taught that Christ had two natures, divine and human, but that he became progressively more divine. He also published a number of works about interpreting the scriptures during the 1550s, often responding to the rebuttals of the Lutheran Reformer Matthias Flacius Illyricus.[2]

Schwenckfeld's Theriotropheum Silesiae is considered the world's oldest published local faunal list, containing a list of the animals of Silesia, including 150 bird species.[3][4]

Death

editIn 1561, Schwenckfeld became sick with dysentery, and gradually grew weaker until he died in Ulm on the morning of December 10, 1561. Due to his enemies, the fact of his death and the place of his burial were kept secret.

Schwenkfelder Church

editSchwenckfeld did not organize a separate church during his lifetime, but followers seemed to gather around his writings and sermons. In 1700, there were about 1,500 of them in Lower Silesia. Many fled Lower Silesia under persecution of the Austrian emperor, and some found refuge on the lands of Count Nicolaus Ludwig Zinzendorf and his Herrnhuter Brüdergemeine. These followers became known as Schwenkfelders. A group arrived in Philadelphia in 1731, followed by five more migrations up to 1737. In 1782, the Society of Schwenkfelders was formed, and in 1909 the Schwenkfelder Church was organized.

Schwenkfelder Church has remained small with approximately 2,695 total members as of 2010, and four churches, including Schwenkfelder Missionary Church in Philadelphia. Each of its the existing churches are within a 50 mi (80 km) radius of Philadelphia.

Schwenkfelder Library & Heritage Center

editSchwenkfelder Library & Heritage Center is a small museum, library and archives in Pennsburg, Pennsylvania. It is the only institution dedicated to the preservation and interpretation of the history of Schwenkfelder, including Schwenckfeld, the Radical Reformation, religious toleration, the Schwenkfelders in Europe and America, and the Schwenkfelder Church. The Schwenkfelder Library & Heritage Center hosts exhibits and programs throughout the year.

Notes

edit- ^ Some sources state he was born in 1490, but late in 1489 appears to be the most commonly reported date of his birth.

- ^ Arbeiten zur Geschichte und Theologie des Luthertums, Neue Folge, Band 5 (Hannover, Lutherisches Verlagshaus: 1984).

- ^ Haffer, J. (2007). "The development of ornithology in central Europe". Journal of Ornithology. 148: 125–153. doi:10.1007/s10336-007-0160-2. S2CID 38874099.

- ^ Andrejew, Adolf (1995). "[Kaspar Schwenckfeldt - a Silesian physician, Renaissance student of nature and bibliophile" (PDF). Kwartalnik Historii Nauki I Techniki R. 40 (5): 89–104. PMID 11624921.

References

edit- Peter C. Erb: Schwenckfeld in his Reformation Setting. Valley Forge, Pa: Judson Press, 1978.

- Edited by Chester David Hartranft et alii: Corpus Schwenkfeldianorum. Vols. 1-19. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1907–1961.

- Paul L. Maier: Caspar Schwenckfeld on the Person and Work of Christ. A Study of Schwenckfeldian Theology at Its Core. Assen, The Netherlands: Royal Van Gorcum Ltd, 1959.

- R. Emmet McLaughlin: Caspar Schwenckfeld, reluctant radical : his life to 1540. New Haven : Yale University Press, 1986 ISBN 0-300-03367-2

- Rufus M. Jones: Spiritual reformers in the 16th and 17th centuries. London: Macmillan, 1914.

- Douglas H. Shantz: Crautwald and Erasmus. A Study in Humanism and Radical Reform in Sixteenth Century Silesia. Baden-Baden: Valentin Koerner, 1992.

External links

edit- Official website

- The Life & Thought of Caspar Schwenckfeld von Ossig on Christianity Today

- Caspar von Schwenckfeld in Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.