Night of the Living Dead is a 1968 American independent horror film directed, photographed, and edited by George A. Romero, written by Romero and John Russo, produced by Russell Streiner and Karl Hardman, and starring Duane Jones and Judith O'Dea. The story follows seven people trapped in a farmhouse in rural Pennsylvania, under assault by flesh-eating reanimated corpses. Although the monsters that appear in the film are referred to as "ghouls", they are credited with popularizing the modern portrayal of zombies in popular culture.

| Night of the Living Dead | |

|---|---|

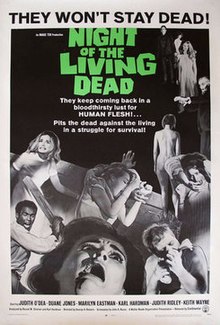

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | George A. Romero |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | George A. Romero |

| Edited by | George A. Romero |

Production company | Image Ten |

| Distributed by | Continental Distributing |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 96 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $114,000–$125,000[2][3] |

| Box office | $30,236,452 (est.)[a] |

Having gained experience creating television commercials, industrial films, and Mister Rogers' Neighborhood segments through their production company The Latent Image, Romero, Russo, and Streiner decided to make a horror film to capitalize on interest in the genre. Their script primarily drew inspiration from Richard Matheson's 1954 novel I Am Legend. Principal photography took place between July 1967 and January 1968, mainly on location in Evans City, Pennsylvania, with Romero using guerrilla filmmaking techniques he had honed in his commercial and industrial work to complete the film on a budget of approximately US$100,000. Unable to procure a proper set, the crew rented a condemned farmhouse to destroy during the course of filming.

Night of the Living Dead premiered in Pittsburgh on October 1, 1968. It grossed US$12 million domestically and US$18 million internationally, earning more than 250 times its budget and making it one of the most profitable film productions of all time. Released shortly before the adoption of the Motion Picture Association of America rating system, the film's explicit violence and gore were considered groundbreaking, leading to controversy and negative reviews. It eventually garnered a cult following and critical acclaim and has appeared on lists of the greatest and most influential films by such outlets as Empire, The New York Times and Total Film. Frequently identified as a touchstone in the development of the horror genre, retrospective scholarly analysis has focused on its reflection of the social and cultural changes in the United States during the 1960s, with particular attention towards the casting of Jones, an African-American, in the leading role.[5] In 1999, the film was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" by the Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry.[6][7][8]

Night of the Living Dead created a successful franchise that includes five sequels released between 1978 and 2009, all directed by Romero. Due to an error when titling the original film, it entered the public domain upon release,[9] resulting in numerous adaptations, remakes, and a lasting legacy in the horror genre. An official remake, written by Romero and directed by Tom Savini, was released in 1990.

Plot

editSiblings Barbra and Johnny drive to a cemetery in rural Pennsylvania to visit their father's grave, where a pale man in a tattered suit kills Johnny and attacks Barbra. She flees to a nearby farmhouse but finds the resident's corpse lying half-eaten on the stairs. A growing horde of ghouls soon surround the house as a stranger, Ben, arrives and initially mistakes Barbra for the homeowner. After driving back several ghouls, he boards the windows and doors. While searching the home for supplies, he locates a lever-action rifle.

A nearly catatonic Barbra is surprised to find people already taking shelter in the home's cellar. Harry, his wife Helen, and their young daughter Karen fled there after a group of the same monsters overturned their car and bit Karen on the arm, leaving her seriously ill. A couple, Tom and Judy, took shelter after hearing an emergency broadcast about a series of brutal killings. Tom and Ben secure the farmhouse while Harry protests that it is unsafe aboveground before returning to the cellar. Ghouls continue to besiege the farmhouse in increasing numbers.

The refugees listen to radio and television reports of an army of cannibalistic corpses committing mass murder across the East Coast of the United States and of the posses of armed men patrolling the countryside to exterminate the living dead. Reports confirm that the ghouls can die again from heavy blows to the head, bullets to the brain, or being burned. Various rescue centers offer refuge and safety, and scientists theorize that radiation from an exploding space probe returning from Venus caused the reanimations.

Ben devises a plan to obtain medical supplies for Karen and transport the group to a rescue center by refueling his truck at a pump on the farm. Ben, Tom, and Judy drive there together, holding the ghouls off with torches and Molotov cocktails. However, the gas from the pump spills and causes the truck to catch fire and explode, killing Tom and Judy. Ben returns and breaks down the door when Harry does not let him in.

The remaining survivors attempt to figure a way out. They pause their discussion to watch the 3 a.m. news update until the power cuts out. The ghouls soon break through the doors and windows of the unlit home. In the chaos, Harry grabs Ben's gun but is disarmed and shot by Ben. Harry staggers down to the cellar and dies next to his daughter.

Karen dies from her injuries, becomes a ghoul, and eats her father's remains. She stabs her mother to death with a masonry trowel. Barbra tries to help Ben keep the ghouls out, but a reanimated Johnny drags her away. As the horde breaks in, Ben takes refuge in the cellar, where he shoots Harry's and Helen's ghouls.

In the morning, an armed posse arrives to dispatch the remaining ghouls. Awoken by their gunfire and sirens, Ben emerges from the cellar, but they shoot him, mistaking Ben for a ghoul. His body is thrown onto a bonfire and burned with the rest of the corpses.

Cast

editThe low-budget film included no well-known actors,[10] but propelled the careers of some cast members.[11] Two independent film companies from Pittsburgh—Hardman Associates and director George A. Romero's The Latent Image—combined to form Image Ten, a production company chartered only to create Night of the Living Dead.[12] The cast consisted of members of Image Ten, actors previously cast for their commercials, acquaintances of Romero, and Pittsburgh stage actors.[13]

- Duane Jones as Ben. The casting was potentially controversial in 1968 when it was rare for a black man to be cast as the hero of an American film primarily composed of white actors, but Romero said that Jones performed the best in his audition.[14] Jones went on to appear in other films, including Ganja & Hess (1973) and Beat Street (1984),[15] but worried that people only recognized him as Ben.[16]

- Judith O'Dea as Barbra. A 23-year-old commercial and stage actress, O'Dea previously worked for Hardman and Eastman in Pittsburgh. O'Dea was in Hollywood seeking entry to the movie business when contacted about the role.[17] O'Dea expressed surprise at the film's cultural impact and the renown it brought her.[18]

- Karl Hardman as Harry Cooper. President of Hardman Associates, Karl Hardman, played the hostile father. Cooper's wife was played by Hardman's real-life business and romantic partner Marilyn Eastman.[19][20]

- Marilyn Eastman as Helen Cooper.[21] Vice president of Hardman Associates, Marilyn Eastman played the doomed mother Helen Cooper and the unnamed, bug-eating zombie. She later appeared in Santa Claws (1996), directed by John Russo.[20][22]

- Kyra Schon as Karen Cooper. Hardman's daughter in real life,[23] 9-year-old Schon also portrayed the mangled corpse on the house's upstairs floor that Ben drags away.[24]

- Keith Wayne as Tom. "Keith Wayne" was Ronald Keith Hartman's stage name.[24] After this lone acting role, Wayne went on to work as a singer, dancer, musician, and night-club owner.[25][24] Wayne became a successful chiropractor in North Carolina.[25] Wayne explained the change in careers during a 1992 interview, "I am not that person anymore. [...] I got to a point in my life where I wanted to have some control. I didn't want to wake up at 40 or 50 and not be in control."[26] In 1995, he took his own life at age 50.[27][28]

- Judith Ridley as Judy. The 19-year-old receptionist from Hardman Associates auditioned for Barbra without any acting experience and was given the less-demanding role of Judy.[29] Ridley starred in Romero's unsuccessful second feature There's Always Vanilla (1971).[30]

- Bill Hinzman, who played the first ghoul encountered by Barbra and Johnny in the cemetery, went on to work on a number of horror films including The Majorettes (1986) and Flesheater (1988).[31][32]

- George Kosana as Sheriff McClelland. Kosana also served as the film's production manager.[33]

- Bill "Chilly Billy" Cardille as himself.[34] Cardille was well known in Pittsburgh as a TV presenter who hosted a horror film anthology series, Chiller Theatre.[35] His daughter Lori would go on to star in Romero's Day of the Dead (1985).[36][37]

Production

editDevelopment and pre-production

edit| External videos | |

|---|---|

| The Calgon Story The creation of a high-budget television commercial for Calgon brand detergent spurred the film's producers to create a horror movie.[38] |

George Romero embarked upon his career in the film industry while attending Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh.[39] He directed and produced television commercials and industrial films for The Latent Image, a company he co-founded with his friend Russell Streiner.[40] The Latent Image started small, but after producing a high-budget Calgon commercial spoofing Fantastic Voyage (1966), Romero felt that the company had the experience and equipment to produce a feature film.[38] They wanted to capitalize on the film industry's "thirst for the bizarre", according to Romero.[41] He, Streiner, and John A. Russo contacted Karl Hardman and Marilyn Eastman, president, and vice president respectively, of a Pittsburgh-based industrial film firm called Hardman Associates, Inc. The Latent Image pitched their idea for a then-untitled horror film.[42]

These discussions led to the creation of Image Ten, a production company chartered to produce a single feature film. The initial budget was $6,000;[12] each member of the production company invested $600 for a share of the profits.[43][b] Ten more investors contributed another $6,000, but this was still insufficient.[44] Production stopped multiple times during filming while Romero used early footage to persuade additional investors.[45] Image Ten eventually raised approximately $114,000 for the budget ($999,000 today).[46][44]

Writing

editThe script was co-written by Russo and Romero. They abandoned an early horror comedy concept about adolescent aliens,[47] after realizing they would not have the budget to create a convincing spaceship.[48] Russo proposed a more constrained narrative where a young man runs away from home and discovers aliens harvesting human corpses for food in a cemetery.[49][50] Romero combined this idea with an unpublished short story about flesh-eating ghouls,[51] and they began filming with an incomplete script.[45][47] According to Russo, the screenplay written prior to filming only covered events up to the emergence of the Cooper family.[52] Russo completed the script while filming and Romero later expanded the final pages of his short story into the sequels Dawn of the Dead (1978) and Day of the Dead (1985).[53]

Romero drew inspiration from Richard Matheson's I Am Legend (1954),[54][c] a horror novel about a plague that ravages a futuristic Los Angeles. The infected in I Am Legend become vampire-like creatures and prey on the uninfected.[55][44][56] Matheson described Romero's interpretation as "kind of cornball",[57] and more theft than homage.[58] In an interview, Romero contrasted Night of the Living Dead with I Am Legend. He explained that Matheson wrote about the aftermath of a complete global upheaval; Romero wanted to explore how people would respond to that kind of disaster as it developed.[59]

Much of the dialogue was altered, rewritten, or improvised by the cast.[60] Lead actress Judith O'Dea told an interviewer, "I don't know if there was an actual working script! We would go over what basically had to be done, then just did it the way we each felt it should be done".[18] One example offered by O'Dea concerns a scene where Barbra tells Ben about Johnny's death. O'Dea said that the script vaguely had Barbra talk about riding in the car with Johnny before they were attacked. She described Barbra's dialogue for the scene as entirely improv.[61] Eastman modified the scenes written for Helen and Harry Cooper in the cellar.[42] Karl Hardman attributed Ben's lines to lead actor Duane Jones. Ben was an uneducated truck driver in the script until Jones began to rewrite his character.[62][42]

The lead role was initially written for a white actor, but upon casting black actor Duane Jones, Romero intentionally did not alter the script to reflect this.[63] The film appeared in theaters at a time when very few black actors played leading roles. The rare exceptions, like the consciously black heroes played by Sidney Poitier, were written as subservient to make those characters palatable to white audiences.[64][65] Asked in 2013 if he took inspiration from the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in the same year that the movie was made, Romero responded in the negative, noting that he only heard about the shooting when he was on his way to find distribution for the finished film.[63]

Filming

editPrincipal photography

editThe small budget dictated much of the production process.[42][66] Scenes were filmed near Evans City, Pennsylvania, 30 miles (48 km) north of Pittsburgh in rural Butler County;[67] the opening sequence was shot at the Evans City Cemetery on Franklin Road, south of the borough.[68][d] Lacking the money to build or purchase a house for the main set, the filmmakers rented a nearby farmhouse scheduled for demolition. Though it lacked running water, some crew members slept there during the shooting, taking baths in a nearby creek.[71] The building's neglected cellar was not a viable location for filming, so the few basement scenes were shot beneath The Latent Image offices.[72] The basement door shown in the film was cut into a wall by the production team and led nowhere.[73]

Props and special effects were simple and limited by the budget. The blood, for example, was Bosco Chocolate Syrup drizzled over cast members' bodies.[74] The human flesh consumed by ghouls consisted of meat and offal donated by an investor's butcher shop.[75][76] Zombie makeup varied during the film. Initially, makeup was limited to white skin with blackened eyes. As filming progressed, mortician's wax simulated wounds and decaying flesh.[77] Filming took place between July 1967 and January 1968 under various titles. Work began under the generic working title Monster Flick, was changed to Night of Anubis after Romero's short story that provided the basis for the script, and was completed as Night of the Flesh Eaters, a title not used in the final release due to a potential conflict with a similarly named film.[78][79][80] The small budget led Romero to shoot on 35 mm black-and-white film. The completed film ultimately benefited from the decision, as film historian Joseph Maddrey describes the black-and-white filming as "guerrilla-style", resembling "the unflinching authority of a wartime newsreel". He found the exploitation film to resemble a documentary on social instability.[81]

Directing

editNight of the Living Dead was the first feature-length film directed by George A. Romero. His initial work involved filming advertisements, industrial films, and shorts for Pittsburgh public broadcaster WQED's children's series Mister Rogers' Neighborhood.[82][83][84] Romero's decision to direct Night of the Living Dead launched his career as a horror director. He took the helm of the sequels as well as Season of the Witch (1972), The Crazies (1973), Martin (1978), Creepshow (1982) and The Dark Half (1993).[85][86] Critics saw the influence of the horror and science-fiction films of the 1950s in Romero's directorial style. Stephen Paul Miller, for instance, witnessed "a revival of fifties schlock shock ... and the army general's television discussion of military operations in the film echoes the often inevitable calling-in of the army in fifties horror films". Miller admits that "Night of the Living Dead takes greater relish in mocking these military operations through the general's pompous demeanor" and the government's inability to source the zombie epidemic or protect the citizenry.[87] Romero described the film's intended mood as a downward arc from near hopelessness to complete tragedy. Film historian Carl Royer praised the film's sophistication—especially considering Romero's limited experience—and noted the use of chiaroscuro (film noir style) lighting to create a mood of increasing alienation.[88]

Night was visually influenced by Golden Age horror comics.[89] The EC Comics books that Romero read as a child were graphic stories set in modern America. They often featured brutal deaths and reanimated corpses seeking revenge on the living.[90] Romero said that he tried to bring into the film the "real hard shadows and weird angles and beautiful lighting that a comic book artist can create."[91] He later collaborated with horror writer Stephen King and former EC Comics artists on the homage Creepshow.[92]

While some critics dismissed Romero's film because of the graphic scenes, writer R. H. W. Dillard claimed that the "open-eyed detailing" of taboo heightened the film's success. He asked, "What girl has not, at one time or another, wished to kill her mother? And Karen, in the film, offers a particularly vivid opportunity to commit the forbidden deed vicariously."[93] Romero featured social taboos as key themes, especially cannibalism. Film historian Robin Wood interprets the flesh-eating scenes of Night of the Living Dead as a late-1960s critique of American capitalism. Wood argues that the zombies' consumption of people represents the logical endpoint of human interactions under capitalism.[94]

Post-production

editMembers of Image Ten were involved in filming and post-production, participating in loading camera magazines, gaffing, constructing props, recording sounds and editing.[95] Production stills were shot and printed by Karl Hardman, assisted by a "production line" of other cast members.[42] Upon completion of post-production, Image Ten found it difficult to secure a distributor willing to show the film with the gruesome scenes intact. Columbia rejected the film for its lack of color, and American International Pictures declined after requests to soften it and re-shoot the final scene were rejected by producers.[45] The Walter Reade Organization agreed to show the film uncensored but changed the title from Night of the Flesh Eaters to Night of the Living Dead because of an existing film with a similar title. While changing the title, the copyright notice was accidentally deleted from the early releases of the film.[9][96]

Soundtrack

editThe film's music consisted of existing pieces that were mixed or modified for the film. Much of the soundtrack had been used by previous films.[e] Romero selected tracks from the Hi-Q music library, and Hardman cut them to match the scenes and augmented them with electronic effects.[98][42] A soundtrack album featuring music and dialogue cues from the film was compiled and released on LP by Varèse Sarabande in 1982. In 2008, the recording group 400 Lonely Things released the album Tonight of the Living Dead, an instrumental album with music and sounds sampled from the 1968 film.[99]

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Driveway to the Cemetery (Main Theme)" | Spencer Moore | 02:19 |

| 2. | "At the Gravesite/Flight/Refuge" | William Loose/Loose—Seely/W. Loose | 03:42 |

| 3. | "Farmhouse/First Approach" | Geordie Hormel | 01:16 |

| 4. | "Ghoulash (J.R.'s Demise)" | Ib Glindemann | 03:30 |

| 5. | "Boarding Up" | G. Hormel/Loose—Seely/Glindemann | 03:00 |

| 6. | "First Radio Report/Torch on the Porch" | Phil Green/G. Hormel | 02:27 |

| 7. | "Boarding Up 2/Discovery: Gun 'n Ammo" | G. Hormel | 02:07 |

| 8. | "Cleaning House" | S. Moore | 01:36 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9. | "First Advance" | Ib Glindemann | 02:43 |

| 10. | "Discovery of TV/Preparing to Escape/Tom & Judy" (All the samples of the track were composed by Geordie Hormel) | G. Hormel/J. Meakin/J. Meakin | 04:20 |

| 11. | "Attempted Escape" | G. Hormel | 01:29 |

| 12. | "Truck on Fire/Ben Attacks Harry/Leg of Leg*" (*electronic sound effects by Karl Hardman) | G. Hormel | 03:41 |

| 13. | "Beat 'Em or Burn 'Em/Final Advance" (Final Advance was composed by Harry Bluestone and Emil Cadkin) | G. Hormel | 02:50 |

| 14. | "Helen's Death*/Dawn/Posse in the Fields/Ben Awakes" (*electronic sound effects by Karl Hardman) | S. Moore | 03:05 |

| 15. | "O.K. Vince/Funeral Pyre (End Title)" | S. Moore | 01:10 |

Release

editPremiere controversy

editNight of the Living Dead premiered on October 1, 1968, at the Fulton Theater in Pittsburgh.[21] Nationally, it was a Saturday afternoon matinée—typical for horror films at the time—and attracted the usual horror film audience of mainly pre-teens and adolescents.[100][101][102] The MPAA film rating system was not in place until the following month, so children were able to purchase tickets. Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times chided theater owners and parents who allowed children access to a film they were entirely unprepared for. Ebert noted that the children in the audience initially displayed typical reactions to '60s horror films, including shouting when ghouls appeared on the screen. He said that the atmosphere in the theater shifted to grim silence as the protagonists each began to fail, die, and be consumed—either by fire or the undead.[102] The deaths of Ben, Barbra, and the supporting cast showed audiences an uncomfortable, nihilistic outlook that was unusual for the genre.[103] According to Ebert:

The kids in the audience were stunned. There was almost complete silence. The movie had stopped being delightfully scary about halfway through, and had become unexpectedly terrifying. There was a little girl across the aisle from me, maybe nine years old, who was sitting very still in her seat and crying ... It's hard to remember what sort of effect this movie might have had on you when you were six or seven. But try to remember. At that age, kids take the events on the screen seriously, and they identify fiercely with the hero. When the hero is killed, that's not an unhappy ending but a tragic one: Nobody got out alive. It's just over, that's all.[102]

A review in Variety denounced the movie as a moral failing of the film's makers, the horror genre, and regional cinema.[104] The reviewer claimed that the "unrelieved orgy of sadism" was effectively pornography due to its extreme violence.[105] These early denouncements would not limit the film's commercial success or later critical recognition.[106]

Critical reception

editIn 1969, George Abagnalo published the film's first positive critical review in the fourth issue of Warhol's Interview magazine.[107] That issue also contained an interview of director George A. Romero by Abagnalo along with William Terry Ork.[108] The review and interview are known as the first acknowledgements of the importance of the film.[109][110][111]

Five years after the film's premiere, Paul McCullough of Take One observed that Night of the Living Dead was the "most profitable horror film ever ... produced outside the walls of a major studio".[112] In the decade after its release, the film grossed over $15 million at the U.S. box office. It was translated into over 25 languages.[113] The Wall Street Journal reported that it was the top-grossing film in Europe in 1968.[93][93] In a 1971 Newsweek article, Paul D. Zimmerman noted that the film had "become a bona fide cult movie for a burgeoning band of blood-lusting cinema buffs".[114]

Decades after its release, the film enjoys a reputation as a classic and still receives positive reviews.[115][116][117] In 2008, the film was ranked by Empire magazine No. 397 of The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time.[118] The New York Times also placed the film on their Best 1000 Movies Ever list.[119] In January 2010, Total Film included the film on its list of The 100 Greatest Movies of All Time.[120] Rolling Stone named Night of the Living Dead one of The 100 Maverick Movies in the Last 100 Years.[121] Reader's Digest found it to be the 12th scariest movie of all time.[122] On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 95% of 84 critics' reviews are positive, with an average rating of 8.9/10. The website's consensus reads: "George A. Romero's debut set the template for the zombie film, and features tight editing, realistic gore, and a sly political undercurrent."[123] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 89 out of 100, based on 17 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[124]

Night of the Living Dead was awarded two distinguished honors decades after its debut. The Library of Congress added the film to the National Film Registry in 1999 with other films deemed "culturally, historically or aesthetically significant".[6][33][125][126] In 2001, the film was ranked No. 93 by the American Film Institute on their AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Thrills list, a list of America's most heart-pounding movies.[127] The zombies in the picture were also a candidate for AFI's AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Heroes & Villains, in the villains category, but failed to make the official list.[128] The Chicago Film Critics Association named it the 5th scariest film ever made.[129] The film also ranked No. 9 on Bravo's The 100 Scariest Movie Moments.[130]

New Yorker critic Pauline Kael called the film "one of the most gruesomely terrifying movies ever made – and when you leave the theatre you may wish you could forget the whole horrible experience. ... The film's grainy, banal seriousness works for it – gives it a crude realism".[131] A Film Daily critic commented, "This is a pearl of a horror picture that exhibits all the earmarks of a sleeper."[132] While Roger Ebert criticized the matinée screening, he admitted that he "admires the movie itself".[102] Critic Rex Reed wrote, "If you want to see what turns a B movie into a classic ... don't miss Night of the Living Dead. It is unthinkable for anyone seriously interested in horror movies not to see it."[133]

Copyright status and home media

editIn the United States, Night of the Living Dead was mistakenly released into the public domain because the original distributor failed to replace the copyright notice when changing the film's name.[9][134] Image Ten displayed a notice on the title frames of the film beneath the original title, Night of the Flesh Eaters, but the Walter Reade Organization removed it when changing the title.[9][135] At that time, United States copyright law held that public dissemination required copyright notice to maintain a copyright.[136] Several years after the film's release, its creators discovered that the original prints distributed to theaters had no copyright protection.[134]

Because Night of the Living Dead was not copyrighted, it has received hundreds of home video releases on VHS, Betamax, DVD, Blu-ray, and other formats.[137] Over two hundred distinct versions of the film have been released on tapes alone.[138] Numerous versions of the film have appeared on DVD, Blu-ray, and LaserDisc with varying quality.[139] The original film is available to view or download for free on many websites.[f] As of September 2024[update], it is the Internet Archive's third most-viewed film, with over 3.5 million views.[148]

The film received a VHS release in 1993 through Tempe Video.[149] The next year, a THX certified 25th anniversary Laserdisc was released by Elite Entertainment. It features special features, including commentary, trailers, gallery files, and more.[150] In 1999, Russo's revised version of the film, Night of the Living Dead: 30th Anniversary Edition, was released on VHS and DVD by Anchor Bay Entertainment.[149] In 2002, Elite Entertainment released a special edition DVD featuring the original cut.[149] Dimension Extreme released a restored print of the film on DVD.[149] This was followed by a 4K restoration Blu-ray released by The Criterion Collection on February 13, 2018, sourced from the original camera negative owned by the Museum of Modern Art and acquired by Janus Films.[151][152] This release also features a workprint edit of the film under the title of Night of Anubis, in addition to various bonus materials.[153] In February 2020, Netflix took down Night of the Living Dead from its streaming service in Germany following a legal request in 2017 because "a version of the film is banned in that country."[154][155]

Revisions

editThere are numerous revised versions of the film with content added, deleted, rearranged, or more heavily modified. From its initial release into the public domain, Night of the Living Dead was widely screened from inferior prints in grindhouse theaters, a trend that continued among the bottom-tier home video companies. The first major revisions of Night of the Living Dead involved colorization by home video distributors. Hal Roach Studios released a colorized version in 1986 that featured ghouls with pale green skin.[156][157] Another colorized version appeared in 1997 from Anchor Bay Entertainment with grey-skinned zombies.[158] In 2009, Legend Films co-produced a colorized 3D version of the film with PassmoreLab, a company that converts 2-D film into 3-D format.[159] The film was theatrically released on October 14, 2010.[160] According to Legend Films founder Barry Sandrew, Night of the Living Dead is the first entirely live action 2-D film to be converted to 3-D.[161]

In 1999, co-writer Russo released a modified version called Night of the Living Dead: 30th Anniversary Edition.[162] He wrote and directed additional scenes and recorded a revised soundtrack composed by Scott Vladimir Licina, who also played the role of Reverend John Hicks. Bill Hinzman, in addition to serving as cinematographer for the new scenes, also reprised his role as Zombie No. 1, who gets an extended backstory of a convicted child murderer who was executed and rose again as a zombie on his burial day. In an interview with Fangoria magazine, Russo explained that he wanted to "give the movie a more modern pace".[163] Russo took liberties with the original script. The additions are neither clearly identified nor even listed. Entertainment Weekly reported "no bad blood" between Russo and Romero. The magazine quoted Romero as saying, "I didn't want to touch Night of the Living Dead".[164] Critics disliked the revised film, notably Harry Knowles of Ain't It Cool News, who promised to permanently ban anyone from his publication who offered positive criticism of the film.[165][166]

A collaborative animated project known as Night of the Living Dead: Reanimated was screened at several film festivals[167] and was released onto DVD on July 27, 2010, by Wild Eye Releasing.[168][169] This project aims to "reanimate" the 1968 film by replacing Romero's celluloid images with animation done in a wide variety of styles by artists from around the world, laid over the original audio from Romero's version.[170] Night of the Living Dead: Reanimated was nominated in the category of Best Independent Production (film, documentary or short) for the 8th Annual Rondo Hatton Classic Horror Awards.[171]

Starting in 2015, and working from the original camera negatives and audio track elements, a 4K digital restoration of Night of the Living Dead was undertaken by the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and The Film Foundation.[172] The fully restored version was shown in November 2016 as part of To Save and Project: The 14th MoMA International Festival of Film Preservation.[173][174] This same restoration was released on Blu-ray by The Criterion Collection on February 13, 2018,[151] and on Ultra HD Blu-ray on October 4, 2022.[175]

Related works

editRomero's Dead films

editNight of the Living Dead is the first of six ... of the Dead films directed by George Romero. Following the 1968 film, Romero released Dawn of the Dead, Day of the Dead, Land of the Dead, Diary of the Dead and Survival of the Dead.[176] Each film traces the evolution of the living dead epidemic in the United States and humanity's desperate attempts to cope with it. As in Night of the Living Dead, Romero peppered the other films in the series with critiques specific to the periods in which they were released.[177][178][179] Romero died with several "Dead" projects unfinished, including the posthumously completed novel The Living Dead[180] and the upcoming film The Twilight of the Dead.[181]

Return of the Living Dead series

editThe Return of the Living Dead series takes place in an alternate continuity where both the original film and the titular living dead exist. The series has a complicated relationship with Romero's Dead films.[182] Co-writer John Russo wrote the novel Return of the Living Dead (1978) as a sequel to the original film and collaborated with Night alumni Russ Streiner and Rudy Ricci on a screenplay under the same title. In 1981, investment banker Tom Fox bought the rights to the story. Fox brought in Dan O'Bannon to direct and rewrite the script, changing nearly everything but the title.[183][184] O'Bannon's The Return of the Living Dead arrived in theaters in 1985 alongside Day of the Dead. Romero and his associates attempted to block Fox from marketing his film as a sequel and demanded the name be changed. In a previous court case, Dawn Associates v. Links (1978), they had prevented Illinois-based film distributor William Links from re-releasing an unrelated film under the title Return of the Living Dead. Fox was forced to cease his advertising campaign but allowed to retain the title.[185][184][186][187]

Rise of the Living Dead

editGeorge Cameron Romero, the son of director George A. Romero, wrote a prequel to his father's classic, under the working titles Origins and Rise of the Living Dead. George Cameron Romero said that he created Rise of the Living Dead as an homage to his father's work, a glimpse into the political turmoil of the mid-to-late 1960s, and a bookend piece to his father's original story. Despite raising funds for the film on Indiegogo in 2014,[188] as of 2023 the film has yet to go into production.[189] In April 2021, Heavy Metal magazine published the first issue of a graphic novel adaptation of the story titled The Rise from Romero's script and with art by Diego Yapur.[190][191]

Remakes and other related films

editMany remakes have attempted to reimagine the original film's story, most notably the 1990 remake written by Romero and directed by special effects artist Tom Savini. Savini had planned to work on the 1968 film before being drafted into the Vietnam War,[192][193] and, after the war, worked with Romero on the sequels.[194] The remake was based on the original screenplay but included a revised plot that portrayed Barbra (Patricia Tallman) as a capable and active heroine.[195] Film historian Barry Grant interprets the new Barbara as a reversal of the original film's portrayal of feminine passivity.[196] He explores how the 1990 Barbra embodies—arguably masculine—virtuous professionalism, as depicted in the works of classic Hollywood director Howard Hawks, a major influence on Romero.[197] Grant describes her as the film's only Hawksian professional. After changing from a mousy outfit that mirrors the original into the visually militaristic clothing she discovers in the farmhouse, Barbra is the lone character able to separate her emotions from the objective necessity to exterminate the living dead.[198] According to Grant, Romero is able to offer one of the most important feminist outlooks in horror because the undead disrupt all traditional values including patriarchy.[199]

Due to its public domain status, many independent producers have created remakes of Night of the Living Dead.[9][134] The film has been remade more than any other movie.[200] Independent remakes have used the film's titular "living dead" as an allegory for racial tension, terrorism, nuclear war, and beyond.[200]

In other media

editIn 1988, Savage Software released a text adventure on the TRS-80 Color Computer titled "Night of the Living Dead", based off of the film, offering a $500 prize for the first person who could demonstrate having beat the game.[201]

At the suggestion of Bill Hinzman (the actor who played the zombie that first attacks Barbra in the graveyard and kills her brother Johnny at the beginning of the original film), composers Todd Goodman and Stephen Catanzarite composed an opera Night of the Living Dead based on the film.[202] The Microscopic Opera Company produced its world premiere, which was performed at the Kelly-Strayhorn Theater in Pittsburgh, in October 2013.[203] The opera was awarded the American Prize for Theater Composition in 2014.[204]

A play called Night of the Living Dead Live! was published in 2017[205] and has been performed in major cities including Toronto, Leeds and Auckland.[206][207][208]

Legacy

editRomero revolutionized the horror film genre with Night of the Living Dead; according to Almar Haflidason of the BBC, the film represented "a new dawn in horror film-making".[209] The film ushered in the splatter film subgenre. Earlier horror films had largely involved rubber masks, costumes, cardboard sets, and mysterious figures lurking in the shadows. They were set in locations far removed from rural and suburban America.[210] Romero revealed the power behind exploitation and setting horror in ordinary, unexceptional locations and offered a template for making an effective film on a small budget.[211] Night spawned countless imitators in cinema, television, and video gaming.[7] According to author Barry Keith Grant, the slasher films of the 1970s and 1980s such as John Carpenter's Halloween (1978), Sean S. Cunningham's Friday the 13th (1980), and Wes Craven's A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) are indebted to Romero's use of gore in a familiar setting.[212]

The film is regarded as one of the launching pads for the modern zombie movie,[213] and effectively redefined the "zombie".[214] Before the film's release, the term "zombie" described a concept from Haitian folklore whereby a bokor could reanimate a corpse into an insensate slave.[215] Early zombie films like White Zombie (1932) combined this with racial and postcolonial anxieties.[216] Romero never used the word "zombie" in the 1968 film or its script—using instead, ghoul—because he said that his flesh-eaters were something new.[21][217][218][63] The term "zombie" was retroactively applied to Night after its cannibalistic undead became the dominant zombie concept in the United States,[219] to such an extent that zombie has become a byword for concepts that failed to "die".[220]

According to professor of religious studies Kim Paffenroth, Romero's antagonists broke with earlier traditions of "voodoo zombies" by having no human villain in control of the zombie and thus no potential to ever restore the monsters' humanity.[221] Compared to the vampires and Haitian zombies that served as inspiration, Romero's antagonists derive more horror from abjection, the disgust that arises from an inability to separate clean from corrupt. While the vampire myth offers a potential escape from mundane life, the zombie offers an infinite decay more abject than conventional death.[222] Cultural critic Steven Shaviro has remarked that—unlike with other movie characters—audiences cannot identify with the zombies because there is no identity left within their bodies, and that they instead provide audiences a combination of disgust and fascinated attraction.[214][223]

Critical analysis

editSince its release, many critics and film historians have interpreted Night of the Living Dead as a subversive film that critiques 1960s American society, international Cold War politics and domestic racism.[65] Film historian Robin Wood organized "The American Nightmare"—a sixty-film retrospective combining screenings and director interviews to frame horror in terms of oppression and repression—for the 1979 Toronto International Film Festival. His essay from the program notes, "An Introduction to the American Horror Film", was highly influential, especially in film criticism where horror as a genre had not previously been considered a topic for serious analysis.[224][225] Wood interprets notable horror films including Night through a psychoanalytic framework.[226] He discusses how traits deemed unacceptable are repressed on the personal level or when not repressed, oppressed on the societal level.[226] He identifies repressed taboos and othered groups as the psychological basis for horror monsters.[226] Wood and later critics used this framework to discuss Night as a commentary on repressed sexuality, the marginalized groups of 1960s America, and the disruption to societal norms resulting from the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War.[227][228]

Elliot Stein of The Village Voice sees the film as an ardent critique of American involvement in the Vietnam War, arguing that it "was not set in Transylvania, but Pennsylvania – this was Middle America at war, and the zombie carnage seemed a grotesque echo of the conflict then raging in Vietnam".[229] Film historian Sumiko Higashi concurs, arguing that Night of the Living Dead draws from the visual vocabulary the media used to report on the war, noting especially that the photographs of the napalm girl and the execution of Nguyễn Văn Lém would be fresh in the minds of the film's creators and audience.[230] She points to aspects of the Vietnam War paralleled in the film: grainy black-and-white newsreels, search and destroy operations, helicopters, and graphic carnage.[231] In 1968, the news was still broadcast in black and white, and the graphic photographs that appear during the closing credits resemble the contemporary Vietnam War photojournalism.[65]

Critics have compared the shooting of the film's black protagonist to the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.[65][232][233] Stein explains, "In this first-ever subversive horror movie, the resourceful black hero survives the zombies only to be surprised by a redneck posse".[229] In 2018, on the film's 50th anniversary, Mark Lager of CineAction noted a clear parallel between the killing and destruction of Ben's body by white police and the violence directed at African Americans during the civil rights movement. Lager described it as a more honest exploration of 1960s America than anything produced by Hollywood.[234]

Night shows influence from Alfred Hitchcock's The Birds.[214] In both films, a small group takes refuge in an isolated house and attempts to fend off an inexplicable attack.[235] Film historian Robin Wood comments that the zombies and birds both function as projections of the familial tensions.[236] The living dead appear during a familial dispute at the cemetery, and the danger escalates as familial resent builds in the farmhouse.[237] Professor of Film Studies Carter Soles argues that the films offer different perspectives on an "environmental apocalypse".[238] Hitchcock's birds were a force of nature, but Romero's zombies were a direct product of human actions. Soles argues that this reflects changing cultural attitudes, especially after the 1962 environmental science book Silent Spring made Americans aware of harm done by the pesticide DDT.[239]

Film historian Gregory Waller identifies broad-ranging critiques of American institutions including the nuclear family, private homes, media, government, and "the entire mechanism of civil defense".[240] Film historian Linda Badley explains that the film was so horrifying because the monsters were not creatures from outer space or some exotic environment, but rather that "They're us."[241] In the 2009 documentary film Nightmares in Red, White and Blue, the zombies in the film are compared to the "silent majority" of the U.S. in the late 1960s.[242]

See also

editNotes

edit

- ^ Night of the Living Dead's worldwide box office:

- ^ The initial ten members for which Image Ten gets its name are:

- George A. Romero

- John Russo

- Russell Streiner

- Marilyn Eastman

- Karl Hardman

- Vince Survinski (production manager)

- Richard Ricci (actor)

- Rudy Ricci (actor)

- Gary Streiner (sound)

- Dave Clipper (attorney)

(Kane 2010, p. 22)

- ^ Official film adaptations of Matheson's novel include The Last Man on Earth (1964), The Omega Man (1971), and the 2007 release I Am Legend.

- ^ In 2011, when the cemetery chapel was under warrant for demolition, Gary R. Steiner led a successful effort to raise funding to restore the building.[69][70]

- ^ The opening title music with the car on the road had been used in a 1961 episode of the TV series Ben Casey entitled "I Remember a Lemon Tree" and is also featured in an episode of Naked City entitled "Bullets Cost Too Much". Most of the music in the film had previously been used on the soundtrack for the science-fiction B-movie Teenagers from Outer Space (1959), as well as several pieces used in the classic Steve McQueen western series Wanted Dead or Alive (1958–61). The piece playing when Ben finds the rifle can be heard in a more complete form during the beginning of The Devil's Messenger (1961) starring Lon Chaney Jr. Another piece, accompanying Barbra's flight from the cemetery zombie, was taken from the score for The Hideous Sun Demon (1959) (Kane 2010, pp. 71–72).

- ^ Online hosts include:

Citations

edit- ^ "Night of the Living Dead (X)". British Board of Film Classification. November 18, 1980. Archived from the original on August 5, 2016. Retrieved June 7, 2016.

- ^ a b Hughes, Mark (October 30, 2013). "The Top Ten Best Low-Budget Horror Movies of All Time". Forbes. Archived from the original on December 27, 2014. Retrieved December 27, 2014.

- ^ "Night of the Living Dead (1968)". AFI Catalog of Feature Films: The First 100 Years 1893–1993. American Film Institute. December 21, 2021. Archived from the original on December 20, 2021. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ "Night of the Living Dead". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on May 31, 2023. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

- ^ Klawans, Stuart (February 13, 2018). "Night of the Living Dead: Mere Anarchy Is Loosed". The Criterion Collection. Archived from the original on January 23, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- ^ a b Allen, Jamie (November 16, 1999). "U.S. film registry adds 25 new titles". Entertainment. CNN. Archived from the original on June 16, 2020. Retrieved November 20, 2017.

- ^ a b Maçek III, J.C. (June 14, 2012). "The Zombification Family Tree: Legacy of the Living Dead". PopMatters. Archived from the original on July 3, 2017. Retrieved October 18, 2017.

- ^ "Preserving the Silver Screen (December 1999) – Library of Congress Information Bulletin". www.loc.gov. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Boluk & Lenz 2011, p. 5.

- ^ Sandell, Scott (July 21, 2017). "Classic Hollywood: George Romero, Mr. Rogers and the Pittsburgh connection". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 22, 2023. Retrieved October 22, 2023.

- ^ Kane 2010, ch. 4.

- ^ a b Kane 2010, pp. 20–23.

- ^ Kane 2010, ch. 4, pp. 42–48.

- ^ Jones 2005, p. 118.

- ^ Fraser, C. Gerald (July 28, 1988). "Duane L. Jones, 51, Actor and Director of Stage Works, Dies". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 4, 2011. Retrieved January 24, 2012.

- ^ Jones, Duane (2002). Bonus interviews. Night of the Living Dead (DVD). Millennium Edition. Elite Entertainment.

- ^ Collum 2004, pp. 3–9.

- ^ a b Collum 2004, p. 4.

- ^ "Night of the Living Dead Cast and Crew – Karl Hardman". www.image-ten.com. Archived from the original on August 26, 2023. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- ^ a b Barnes, Mike (August 23, 2021). "Marilyn Eastman, Actress and Vital Behind-the-Scenes Player on 'Night of the Living Dead,' Dies at 87". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on August 26, 2023. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- ^ a b c Collum 2004, p. 3.

- ^ Nolan, Emma (August 24, 2021). "Tributes for Marilyn Eastman, 'Night of the Living Dead' Star, Dead at 87". Newsweek. Archived from the original on August 26, 2023. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- ^ Kane 2010, p. 42.

- ^ a b c Kane 2010, p. 43.

- ^ a b Hazlett, Terry (March 14, 1974). "Former Houston Man Heading for Stardom". Observer-Reporter. p. C-6. Archived from the original on January 18, 2020. Retrieved December 30, 2022 – via Google News Archive Search.

- ^ Langford, Bob (December 18, 1992). "A Zombie in His Closet". The News and Observer. Raleigh, North Carolina. pp. 1D, 3D. Archived from the original on August 31, 2023. Retrieved August 30, 2023.

- ^ Kane 2010, p. 204.

- ^ Hartman, Keith (1995). "How to Find Chiropractic Help, Bursitis and Tendinitis, Sternum Noises, Knee and Neck Care; plus the Notice of the Death of Dr. Hartman". Hard Gainer. No. 40. Archived from the original on July 5, 2022.

- ^ Kane 2010, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Kane 2010, pp. 90–92.

- ^ Barton, Steve (February 6, 2012). "Rest in Peace: Bill Hinzman". Dread Central. Archived from the original on August 26, 2023. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- ^ "Night of the Living Dead actor Bill Hinzman dies". BBC News. February 7, 2012. Archived from the original on August 26, 2023. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- ^ a b Barnes, Mike (January 3, 2017). "George Kosana, 'Night of the Living Dead' Actor (and Investor), Dies at 81". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on October 19, 2017. Retrieved October 18, 2017.

- ^ Kane 2010, p. 45.

- ^ Hasch, Michael (September 3, 2007). "Bill Cardille marks 50 years on Pittsburgh airwaves". Tribune-Review. Pennsylvania: Total Media LLC. Archived from the original on August 26, 2023. Retrieved September 2, 2023.

- ^ Squires, John (October 26, 2021). "First Image of Original 'Day of the Dead' Cast Reunited in Upcoming 'Night of the Living Dead 2' [Exclusive]". Bloody Disgusting!. Retrieved March 10, 2024.

- ^ Cardille, Lori. "Lori Cardille". Bloody Good Horror (Interview). Interviewed by Eric N. Retrieved March 10, 2024.

- ^ a b Kane 2010, p. 28.

- ^ Kane 2010, p. 25.

- ^ Kane 2010, pp. 26–27.

- ^ "George A Romero, godfather of zombie horror – obituary". The Telegraph. July 17, 2017. Archived from the original on August 27, 2023. Retrieved August 27, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Hardman, Karl; Eastman, Marilyn. "Interview with Karl Hardman and Marilyn Eastman". Homepage of the Dead (Interview). Archived from the original on November 7, 2015. Retrieved October 16, 2017.

- ^ Thorne, Will (January 3, 2017). "'Night of the Living Dead' Actor George Kosana Dies at 81". Variety. Archived from the original on January 4, 2017. Retrieved January 4, 2017.

- ^ a b c Russo 1985, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b c Peary 1981, p. 227.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ a b Kane 2010, p. 23.

- ^ Kane 2010, p. 21.

- ^ Russo 1985, pp. 31, 61.

- ^ Kane 2010, pp. 20–24.

- ^ Bishop 2006, p. 199.

- ^ Surmacz 1975, p. 16.

- ^ Romero, George A. (February 2, 1997). "George A. Romero interview". Forbidden Weekend (Interview). BBC2.

- ^ Dinello 2006, p. 257.

- ^ Paffenroth 2006, pp. 138–143.

- ^ Matheson, Richard (1995) [1954]. I Am Legend. Orb Books. ISBN 978-0-312-86504-7.

- ^ Weaver 1999, p. 307.

- ^ Collis, Clark (December 7, 2007). "An Author You Can't Refuse". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on July 31, 2018.

- ^ McConnell, Marianna (January 24, 2008). "Interview: George A. Romero On Diary of the Dead". Cinema Blend. Archived from the original on December 26, 2019.

- ^ Kane 2010, pp. 33–34, 40, 45.

- ^ Collum 2004, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Kane 2010, pp. 32–35.

- ^ a b c Robey, Tim (November 8, 2013). "George A Romero: Why I don't like The Walking Dead". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on December 7, 2020. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

- ^ McGreevy, Nora (January 7, 2022). "How Sidney Poitier Rewrote the Script for Black Actors in Hollywood". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on January 8, 2022. Retrieved January 8, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Harper 2005.

- ^ Newman 2000, p. 57.

- ^ Kane 2010, p. 46.

- ^ Kane 2010, pp. 55–6.

- ^ "Save the Evans City Cemetery Chapel". Living Dead Festival, LLC. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013. Retrieved October 4, 2013.

- ^ Farkas, Rachel (August 31, 2013). "Zombie fans celebrate iconic 'Night of the Living Dead'". TribLIVE. Trib Total Media. Archived from the original on November 16, 2018. Retrieved October 4, 2013.

- ^ Hervey 2008, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Kane 2010, pp. 28, 29, 59.

- ^ McCormick, Colin (February 4, 2021). "10 Hidden Details Everyone Missed In Night Of The Living Dead". ScreenRant. Archived from the original on September 2, 2023. Retrieved September 2, 2023.

- ^ Kane 2010, p. n184.

- ^ Hoberman & Rosenbaum 1983, p. 121.

- ^ Winterhalter, Elizabeth (November 5, 2020). "The D-I-Y Origins of Night of the Living Dead". JSTOR Daily. Archived from the original on September 2, 2023. Retrieved September 2, 2023.

- ^ Kane 2010, pp. 47–49, 58.

- ^ Romero, George A. et al. (2002). Scrapbook. Night of the Living Dead (DVD). Millennium Edition. Elite Entertainment.

- ^ Heffernan 2004, p. 219.

- ^ Hart, Adam Charles. "Night of the Flesh Eaters mini-banners". Horror Studies Collection. University of Pittsburgh Library Systems. Archived from the original on September 2, 2023. Retrieved September 2, 2023.

- ^ Maddrey 2004, p. 51.

- ^ "George A. Romero Bio". Dawn of the Dead (DVD) (Special Divimax ed.). Anchor Bay. 2004..

- ^

- Romero, George A. (January 7, 2004). "Bloody Diary: Part 1". diamonddead.com. Archived from the original on February 14, 2007.

- Romero, George A. (January 15, 2004). "Bloody Diary: Part 2". diamonddead.com. Archived from the original on February 16, 2007.

- Romero, George A. (January 28, 2004). "Bloody Diary: Part 3". diamonddead.com. Archived from the original on October 26, 2006.

- ^ Reigle, Matt (March 30, 2022). "How Mr Rogers Gave Night Of The Living Dead Director George Romero His Start". Grunge. Archived from the original on September 4, 2023. Retrieved September 4, 2023.

- ^ Gallagher, Declan (August 17, 2023). "George Romero movies, ranked". EW.com. Archived from the original on September 4, 2023. Retrieved September 4, 2023.

- ^ "George A. Romero". Center for the Book. Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Libraries. Archived from the original on September 4, 2023. Retrieved September 4, 2023.

- ^ Miller 1999, p. 81.

- ^ Royer 2005, p. 15.

- ^ Chute 1982, p. 15.

- ^ Hervey 2008, p. 36.

- ^ Selby 2004, 43:40.

- ^ Selby 2004, 44:25.

- ^ a b c Dillard & Waller 1988, p. 15.

- ^ Wood 1985, p. 213.

- ^ Russo 1985, p. 7.

- ^ Mulligan, Rikk; Prisbylla, Andy; Scherer, David. "Legacy of the Dead: Zombie Redux". CMU Libraries. Carnegie Mellon University. Archived from the original on September 4, 2023. Retrieved September 4, 2023.

- ^ Drogla, Paul (2015). "Des Krieges neue Kinder. Überlegungen zur Ikonografie des Zombiearchetyps im Kontext des Vietnamkriegs" [New Children of War: On the Iconography of the Zombie Archetype in the Context of the Vietnam War]. Zeitschrift für Fantastikforschung (in German) (2): 31:24.

[...] Lehrfilms Fallout: When and How to Protect Yourself Against (USA 1959, produziert von Creative Arts Studio Inc. im Auftrag des Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization). Was im Aufklärungsfilm einleitend Aufnahmen von Nuklearexplosionen begleitet, unterlegt in NIGHT die dokumentierte Katastrophe im Abspann (vgl. Höltgen 23).

[[...] educational film Fallout: When and How to Protect Yourself Against It (USA 1959, produced by Creative Arts Studio Inc. on behalf of the Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization). What accompanies the introductory shots of nuclear explosions in the educational film is accompanied by the documented catastrophe in the end credits in NIGHT (cf. Höltgen 23).] - ^ Kane 2010, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Corupe, Paul (August 2009). "They're Coming to Remix You, Barbra". Rue Morgue (92): 63.

- ^ Russo 1985, p. 70.

- ^ Heffernan 2002, pp. 59–60.

- ^ a b c d Ebert, Roger (January 5, 1969). "Night of the Living Dead". Chicago Sun-Times. Chicago. Archived from the original on March 14, 2015. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- ^ Jones 2005, pp. 117–18.

- ^ "'Night of the Living Dead': Film Review". Variety. October 15, 1968. Retrieved July 23, 2024.

- ^ Russell 2008, p. 65.

- ^ Paffenroth 2006, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Abagnalo, George (1969). "Night of the Living Dead" (PDF). Interview. 1 (4): 23.

- ^ Ork, Terry; Abagnalo, George (1969). "Night of the Living Dead – Interview with George A. Romero". Interview. 1 (4): 23.

- ^ Hervey 2008, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Punch, David A. (October 2, 2018). "Night of the Living Dead: Horrors of Reality Manifested in the Flesh". Medium. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ Kuhns, Rob (director) (2014). Birth of the Living Dead. First Run Features (Documentary Film).

- ^ McCullough, Paul (July–August 1973). "A Pittsburgh Horror Story". Take One. Vol. 4, no. 6. p. 8.

- ^ Higashi 1990, p. 175.

- ^ Zimmerman, Paul D. (November 8, 1971). "We Killed 'Em in Pittsburgh". Newsweek. p. 118.

- ^ Rouner, Jef (July 3, 2018). "'Night of the Living Dead': What a zombie classic says about death in America". Houston Chronicle. Hearst Newspapers, LLC.

- ^ Kenny, Glenn (February 16, 2018). "'Night of the Living Dead': Zombies Restored to Their Full Beauty". New York Times. Archived from the original on August 23, 2018. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- ^ Mann, Brian (December 23, 2018). "When An Undead Apocalypse First Swept America In The 'Night Of The Living Dead'". NPR. Archived from the original on April 17, 2023. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time". Empire. Archived from the original on January 18, 2012. Retrieved August 5, 2010.

- ^ "The Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made". The New York Times. April 29, 2003. Archived from the original on June 12, 2008. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- ^ "100 Greatest Movies Of All Time". Features. Total Film. January 25, 2010. p. 7. Archived from the original on May 19, 2011.

- ^ "100 Maverick Movies in the Last 100 Years". Rolling Stone. Published by AMC Filmsite.org. Archived from the original on June 5, 2021. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ "The 31 Scariest Movies of All Time". Reader's Digest. Archived from the original on December 21, 2020. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- ^ "Night of the Living Dead". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved October 12, 2023.

- ^ "Night of the Living Dead". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Retrieved October 31, 2023.

- ^ "Librarian of Congress Names 25 More Films to National Film Registry". Library of Congress. November 16, 1999. Archived from the original on July 7, 2016.. Retrieved June 24, 2006.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Thrills" (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 14, 2019. Retrieved June 24, 2006.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Heroes and Villains: The 400 Nominated Characters" (PDF). afi.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 7, 2011. Retrieved June 6, 2010.

- ^ "Chicago Critics' Scariest Films". AltFilmGuide.com. Archived from the original on February 26, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ^ "Bravo's The 100 Scariest Movie Moments". Archived from the original on October 30, 2007. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ^ Kael 1991, p. 526.

- ^ Higashi 1990, p. 175, Film Daily, review of Night of the Living Dead.

- ^ Petsko 2011, p. 108.

- ^ a b c Kane 2010, pp. 93–94.

- ^ United States Senate, Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on Technology and the Law, Legal Issues that Arise when Color is Added to Films Originally Produced, Sold and Distributed in Black and White (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1988), p. 83.

- ^ "Copyright Notice, Deposit, and Registration". Copyright Law of the United States (Circular 92 ed.). U.S. Copyright Office. sec. Omission of notice on certain copies and phonorecords. Archived from the original on December 18, 2020.

- ^ Hervey 2008, p. 14.

- ^

- Locklin, Kristy (September 16, 2021). "'Night of the Living Tapes' details classic zombie film's record-setting afterlife on VHS". NEXTpittsburgh. Archived from the original on June 6, 2023. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- Turner, Geoff (2021). Night of the Living Tapes. Image Ten. ISBN 979-8598529812.

- Turner, Geoff (2021). "Collector's Checklist" (PDF). nightofthelivingtapes.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- ^ Gingold, Michael (May 19, 2019). "DVD Review: Night of the Living Dead 40th Anniversary Edition". Fangoria. Archived from the original on March 26, 2023. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Egan, Toussaint; Volk, Pete; Goslin, Austen; Staff, Polygon (October 16, 2021). "The best horror movies you can watch right now". Polygon. Archived from the original on September 2, 2023. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- ^ Perry, Nick; Marnell, Blair (September 1, 2023). "The best free movies on YouTube right now (September 2023)". Digital Trends. Archived from the original on September 4, 2023. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- ^ Budowski, Jade (July 26, 2017). "Did You Know You Can Stream A Ton Of Classic Films Online For Free?". Decider. Archived from the original on January 27, 2023. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- ^ Manno, Jackie (October 14, 2022). "10 Terrifying Horror Movies to Watch on Peacock". Archived from the original on October 2, 2023. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ^ a b c Roark, Elijah (February 12, 2023). "5 movies to help celebrate Black History Month". The Reflector. Archived from the original on February 15, 2023. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- ^ Night of the Living Dead at Internet Archive. Retrieved June 24, 2006.

- ^ Night of the Living Dead. Archived from the original on January 25, 2012. Retrieved January 28, 2012 – via Hulu.

- ^ "File:Night of the Living Dead (1968).webm". Wikimedia Commons. 1968. Retrieved October 31, 2023.

- ^ "Most viewed films". Internet Archive. Retrieved September 12, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Kane 2010, p. 205.

- ^ "Night of the Living Dead: 25th Anniversary (1968) THX ELITE [EE1114]". Hollywood Laserdisc. Archived from the original on November 5, 2021. Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- ^ a b "Night of the Living Dead". Criterion Collection. Archived from the original on November 16, 2017. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- ^ Axmaker, Sean (October 6, 2022). "'Night of the Living Dead' restored on HBO Max and Criterion Channel". Stream On Demand. Archived from the original on March 27, 2023. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- ^ Squires, John (November 17, 2017). "Home Video 'Night of Anubis': What to Expect from Criterion's 'Night of the Living Dead' Workprint". Bloody Disgusting. Archived from the original on July 20, 2019. Retrieved November 14, 2019.

- ^ Spangler, Todd (February 7, 2020). "Netflix Reveals All the TV Shows and Movies It's Removed Because of Foreign Government Takedown Demands". Variety. Archived from the original on January 29, 2021. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- ^ Waltz, Amanda. "Report reveals Netflix removed Night of the Living Dead from Germany's streaming services". Pittsburgh City Paper. Archived from the original on August 11, 2023. Retrieved August 11, 2023.

- ^ Kane 2010, p. 157.

- ^ "Night of the living dead. Detailed Record View". United States Copyright Office. June 14, 1991. Archived from the original on July 18, 2023. Retrieved July 17, 2013.

- ^ Night of the Living Dead (VHS, Anchor Bay Entertainment, 1997), ASIN 6301231864.

- ^ "Johnny Ramone Tribute Includes Night of the Living Dead in 3D". Dread Central. Archived from the original on September 24, 2009. Retrieved March 26, 2010.

- ^ "Zombie Classic "Night of the Living Dead, Now in 3D!" Begins Its First Theatrical Run". PRWeb. Vocus. October 17, 2010. Archived from the original on June 3, 2011. Retrieved September 4, 2011.

- ^ ""Night of the Living Dead" to Be Released in Color and 3D". Business Wire. December 23, 2008. Archived from the original on December 26, 2008. Retrieved January 2, 2009.

- ^ Night of the Living Dead: 30th Anniversary Edition (DVD). 1999.

- ^ Kane 2010, p. 174.

- ^ Pinsker, Beth (April 23, 1999). "Return to the Night of the Living Dead". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on September 8, 2023. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- ^ Kane 2010, p. 177.

- ^ Knowles, Harry (September 19, 1999). "NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD – 30th Anniversary DVD Special Edition". Ain't It Cool News. Archived from the original on March 5, 2019. Retrieved October 17, 2017.

- ^

- "Night of the Living Dead Reanimated". Metro Cinema. Archived from the original on March 14, 2016. Retrieved March 26, 2010.

- "Tempe Film: Night of the Living Dead: Reanimated on Thursday 1/28". Events.getoutaz.com. January 28, 2010. Archived from the original on August 7, 2016. Retrieved March 26, 2010.

- "MOHAI's zombie film fest to feature Port Gamble movie". The Seattle Times. September 25, 2009.

- ^ Stevens, Michael (June 18, 2010). "Wild Eye and MVD Resurrect "Night of the Living Dead: Reanimated"". Sneak Peek. Archived from the original on October 19, 2017. Retrieved October 17, 2017.

- ^ "Interview with Night of the Living Dead: Reanimated's Mike Schneider". Shoot for the Head. Archived from the original on November 5, 2013. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ "Official NOTLD:Reanimated Site". Archived from the original on March 31, 2009. Retrieved October 16, 2009.

- ^ "Rondo Hatton Awards 2009 Winners". Rondoaward.com. Archived from the original on February 26, 2018. Retrieved January 19, 2013.

- ^ Bramesco, Charles (November 4, 2016). "Night of the Living Dead has always looked awful, but the 4K restoration is terrific". theverge.com. The Verge. Archived from the original on January 5, 2017. Retrieved January 5, 2017.

- ^ "Night of the Living Dead. 1968. Directed by George A. Romero". moma.org. Museum of Modern Art. Archived from the original on January 6, 2017. Retrieved January 5, 2017.

- ^ "To Save and Project: The 14th MoMA International Festival of Film Preservation". moma.org. Museum of Modern Art. Archived from the original on January 6, 2017. Retrieved January 5, 2017.

- ^ Squires, John (August 2, 2022). "'Night of the Living Dead' Getting 4K Ultra HD Upgrade from Criterion Collection This Halloween". Bloody Disgusting. Archived from the original on July 18, 2023. Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- ^ Millican, Josh (February 15, 2020). "This Day in Horror: 'Diary of the Dead' Was Released 12 Years Ago". Dread Central. Archived from the original on October 30, 2020. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- ^ Schott, Gareth (September 8, 2023). "Dawn of the Digital Dead: The Zombie as Interactive Social Satire in American Popular Culture". Australasian Journal of American Studies. 29 (1): 61–75. JSTOR 41054186. Archived from the original on February 11, 2023. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- ^ Cusson, Katie (March 27, 2023). "Why George Romero Movies Aren't Just About the Horror of Zombies". MovieWeb. Archived from the original on September 1, 2023. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- ^ Benson-Allott, Caetlin (July 18, 2017). "The Defining Feature of George Romero's Movies Wasn't Their Zombies. It Was Their Brains". Slate. Archived from the original on April 23, 2023. Retrieved September 8, 2023 – via slate.com.

- ^ Murray, Noel (August 3, 2020). "George Romero's final project unites all his zombie movies". Polygon. Archived from the original on June 9, 2023. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- ^ Couch, Aaron (April 30, 2021). "'Twilight of the Dead,' George A. Romero's Final Zombie Movie, in the Works (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 20, 2021. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- ^ Kane 2010, pp. 147–153.

- ^ Kane 2010, p. 147.

- ^ a b Fordy, Tom (December 19, 2020). "The horror film that won't die: how Night of the Living Dead spawned a spin-off zombie army". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on October 2, 2023. Retrieved September 23, 2023.

- ^ Kane 2010, ch. 10.

- ^ Patrick J. Flinn, Handbook of Intellectual Property Claims and Remedies: 2004 Supplement (New York: Aspen Publishers, 1999), pp. 24–25, ISBN 978-0-7355-1125-5.

- ^ Dowell, Jonathan (1998). "Bytes and Pieces: Fragmented Copies, Licensing, and Fair Use in a Digital World". California Law Review. 86 (4). California Law Review, Inc: 871–872. doi:10.2307/3481141. JSTOR 3481141.

- ^ Squires, John (November 1, 2017). "George Romero's Son Announces 'Rise of the Living Dead'". Archived from the original on November 2, 2017. Retrieved November 1, 2017.

- ^ "Production Diary". Films Used to be Dangerous. November 26, 2019. Archived from the original on October 2, 2023. Retrieved September 9, 2023.

- ^ Squires, John (March 22, 2021). "'The Rise': Preview George C. Romero's 'Night of the Living Dead' Prologue Comic from Heavy Metal Magazine! [Exclusive]". Archived from the original on May 7, 2021. Retrieved May 6, 2021.

- ^ Romero, George Cameron (w), Yapur, Diego (a). The Rise, no. 1 (April 7, 2021). Heavy Metal.

- ^ Skal 1993, pp. 307–309.

- ^ James, Caryn (October 19, 1990). "The Zombies Return, in Living (or Is It Dead?) Color". The New York Times.

- ^ Grant 2015, p. 230.

- ^ Grant 2015, pp. 228, 230–231.

- ^ Grant 2015, p. 228.

- ^ Grant 2015, pp. 232, 234.

- ^ Grant 2015, p. 234.

- ^ Grant 2015, p. 239.

- ^ a b Ramella, Brynne (November 19, 2020). "Why There Are So Many Night of the Living Dead Remakes". Screen Rant.

- ^ "Night of the Living Dead". MobyGames. Retrieved November 19, 2024.

- ^ Podurgiel, Bob (October 30, 2015). "'Night of the Living Dead' opera arrives in time for Halloween". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on October 31, 2015. Retrieved September 8, 2020.

- ^ "Night of the Living Dead – The Opera". Carnegie Mellon University. Archived from the original on December 4, 2020. Retrieved September 8, 2020.

- ^ "Composition Winners 2014". www.theamericanprize.org. Archived from the original on July 15, 2019. Retrieved May 7, 2021.

- ^ Bond, Christopher; Boyer, Dale; Martin (Screenwriter), Trevor; Lamb, Jamie; Harrison, Christopher; Pattison, Phil (2017). Night of the Living Dead Live. Samuel French. ISBN 978-0-573-70595-3.

- ^ "Night Of the Living Dead Live!". www.nightofthelivingdeadlive.com. Archived from the original on August 2, 2021. Retrieved August 3, 2021.

- ^ Wiegand, Chris (January 14, 2020). "Cue the zombies! Night of the Living Dead remade in real time on stage". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 3, 2021. Retrieved August 3, 2021.

- ^ "Ultimate Collision Of Form Brings Zombies And Cinema To Silo". Scoop News. August 3, 2021. Archived from the original on August 3, 2021. Retrieved August 3, 2021.

- ^ Haflidason, Almar (March 20, 2001). "Night of the Living Dead (1968)". BBC. Archived from the original on August 18, 2020. Retrieved June 24, 2006.

- ^ Jones 2005, p. 117.

- ^ Rockoff 2002, p. 35.

- ^ Grant 2015, p. 229.

- ^ Paffenroth 2006, pp. 2–3.

- ^ a b c Stommel 2013.

- ^ Bishop 2006, pp. 198–199.

- ^ Boluk & Lenz 2011, pp. 27, 32–34, 44.

- ^ Tudor 1989, p. 101.

- ^ Poole 2011, pp. 194–195.

- ^ Zimmerman 2013, p. 78.

- ^ Petsko 2011.

- ^ Paffenroth 2006, p. 3.

- ^ Zimmerman 2013, pp. 78–80.

- ^ Shaviro 2017, sec. The Seductiveness of Horror.

- ^ Lowenstein 2022, ch. 1.

- ^ Wood & Lippe 2018, p. 181.

- ^ a b c Wood 1985, sec. I.

- ^ Higashi 1990, p. 176–178.

- ^ Wood 1985, sec. II: Since Psycho.

- ^ a b Stein, Elliot (January 7, 2003). "The Dead Zones: 'George A. Romero' at the American Museum of the Moving Image". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on October 19, 2017. Retrieved December 21, 2015.

- ^ Higashi 1990, p. 184.

- ^ Higashi 1990, p. 181.

- ^ Paffenroth 2006, pp. 38, 157–158, sec. 39.

- ^ Kane 2010, p. 36.

- ^ Lager, Mark (2018). "Night of the Living Dead & Texas Chainsaw Massacre – Race and Capitalism in Trump's America". CineAction. Archived from the original on July 29, 2023. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

- ^ Johnson 2020.

- ^ Wood & Lippe 2018, p. 162.

- ^ Wood & Lippe 2018, pp. 162–164.

- ^ Rust & Soles 2014, p. 511.

- ^ Soles 2014, pp. 526–527.

- ^ Dillard & Waller 1988, p. 4.

- ^ Badley 1995, p. 25.

- ^ Monument, Andrew (director) (2009). Nightmares in Red, White and Blue (motion picture).

References

edit- Badley, Linda (1995). Film, Horror, and the Body Fantastic. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-27523-4.

- Bishop, Kyle (2006). "Raising the Dead: Unearthing the Nonliterary Origins of Zombie Cinema". Journal of Popular Film and Television. 33 (4): 196–205. doi:10.3200/JPFT.33.4.196-205. S2CID 191630456. ProQuest 199456220.

- Boluk, Stephanie; Lenz, Wylie (2011). "Introduction: Generation Z, the Age of Apocalypse". In Boluk, Stephanie; Lenz, Wylie (eds.). Generation Zombie: Essays on the Living Dead in Modern Culture. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-6140-0. Archived from the original on June 5, 2021. Retrieved November 18, 2020.

- Chute, David (September–October 1982). "Films go EC/DC. The Great Frame Robbery". Film Comment. 18 (5). Film Society of Lincoln Center: 13–17. JSTOR 43452895.

- Collum, Jason Paul (2004). Assault of the Killer B's: Interviews with 20 Cult Film Actresses. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-1818-3.

- Dillard, R. H. W.; Waller, Gregory A. (1988). "Night of the Living Dead: It's Not Like Just a Wind That's Passing Through". American Horrors: Essays on the Modern American Horror Film. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-01448-2.

- Dinello, Daniel (2006). Technophobia!: Science Fiction Visions of Posthuman Technology. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-70986-7.

- Grant, Barry Keith (2015) [1996]. "Taking Back the Night of the Living Dead: George Romero, Feminism and the Horror Film". The Dread of Difference: Gender and the Horror Film (2nd ed.). University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292771376.

- Harper, Stephen (November 2005). "Night of the Living Dead: Reappraising an Undead Classic". Bright Lights Film Journal. No. 50.

- Heffernan, Kevin (2002). "Inner-City Exhibition and the Genre Film: Distributing Night of the Living Dead (1968)". Cinema Journal. 41 (3): 59–77. doi:10.1353/cj.2002.0009. S2CID 192213816.

- Heffernan, Kevin (2004). Ghouls, Gimmicks, and Gold: Horror Films and the American Movie Business, 1953–1968. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-3215-2.

- Hervey, Ben A. (2008). Night of the Living Dead. BFI Film Classics. British Film Institute. ISBN 9781839022029.

- Higashi, Sumiko (1990). "Night of the Living Dead: A Horror Film about the Horrors of the Vietnam Era". In Dittmar, Linda; Michaud, Gene (eds.). From Hanoi to Hollywood: The Vietnam War in American Film. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-813-51587-8.

- Hoberman, J.; Rosenbaum, Jonathan (1983). Midnight Movies. New York: Harper and Rowe. ISBN 0060909900.

- Johnson, Steve (December 2, 2020). "Dreams and the Human Material in Night of the Living Dead". Bright Lights.

- Jones, Alan (2005). The Rough Guide to Horror Movies. London: Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-843-53521-8.

- Kane, Joe (2010). Night of the Living Dead: Behind the Scenes of the Most Terrifying Zombie Movie Ever. Citadel Press. ISBN 978-0-806-53331-5.

- Kael, Pauline (1991). 5001 Nights at the Movies. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-0-8050-1367-2.

- Lowenstein, Adam (2022). "1. A Reintroduction to the American Horror Film: Revisiting Robin Wood and 1970s Horror". Horror Film and Otherness (digital ed.). Columbia University Press. pp. 19–44. doi:10.7312/lowe20576-004. ISBN 9780231556156.

- Maddrey, Joseph (2004). Nightmares in Red, White and Blue: The Evolution of the American Horror Film. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-1860-2.

- Miller, Stephen Paul (1999). The Seventies Now: Culture as Surveillance. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-2166-8.

- Newman, Robert (2000). "The Haunting of 1968". South Central Review. 16 (4): 53–61. doi:10.2307/3190076. JSTOR 3190076.