The Kankanaey people are an indigenous peoples of northern Luzon, Philippines. They are part of the collective group of indigenous peoples in the Cordillera known as the Igorot people.

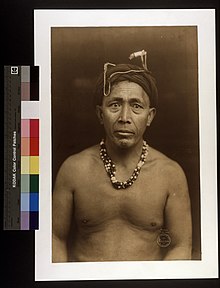

A Kankanaey chief from the town of Suyoc, in Mankayan, Benguet (taken c. 1904). | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 466,970[1] (2020 census) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Kankanaey, Ilocano, Tagalog | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Indigenous folk religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Igorot peoples |

Demographics

editThe Kankanaey live in western Mountain Province, northern Benguet, northeastern La Union and southeastern Ilocos Sur.[2] The Kankanaey of the western Mountain Province are sometimes identified as Applai or Aplai. Because of the differences in culture from the Kankanaey of Benguet, the "Applai" have been accredited as a separate tribe.[3]

Few Kankanaey can be found in some areas in of the Philippines. They form a minority in the Visayas, especially in Cebu, Iloilo and Negros provinces. They can also be found as a minority in Mindanao, particularly in the provinces of Sultan Kudarat in Soccsksargen and Lanao del Norte in Northern Mindanao. [4] [5]

The 2010 Philippines census counted 362,833 self-identifying Kankanaey and 67,763 self-identifying Applai.[6]

Prehistory

editRecent DNA studies show that the Kankanaey along with the Atayal people of Taiwan, were most probably among the original ancestors of the Lapita people and modern Polynesians.[7][8][9] They might even reflect a better genetic match to the original Austronesian mariners than the aboriginal Taiwanese, as the latter were influenced by more recent migrations to Taiwan, whereas the Kankanaey are thought to have remained an isolated relict population.[10]

Northern Kankanaey

editThe Northern Kankanaey or Applai live in Sagada and Besao, western Mountain province, and constitute a linguistic group. H. Otley Beyer believed they originated from a migrating group from Asia who landed on the coasts of Pangasinan before moving to Cordillera. Beyer's theory has since been discredited, and Felix Keesing speculated the people were simply evading the Spanish. Their smallest social unit is the sinba-ey, which includes the father, mother, and children. The sinba-eys make up the dap-ay/ebgan which is the ward. Their society is divided into two classes: the kadangyan (rich), who are the leaders and who inherit their power through lineage or intermarriage, and the kado (poor). They practice bilateral kinship.[11]

The Northern Kankana-eys believe in many supernatural beliefs and omens, and in gods and spirits like the anito (soul of the dead) and nature spirits.[11]

They also have various rituals, such as the rituals for courtship and marriage and death and burial. The courtship and marriage process of the Northern Kankana-eys starts with the man visiting the woman of his choice and singing (day-eng), or serenading her using an awiding (harp), panpipe (diw-as), or a nose flute (kalelleng). If the parents agree to their marriage, they exchange work for a day (dok-ong and ob-obbo), i.e. the man brings logs or bundled firewood as a sign of his sincerity, the woman works on the man’s father’s field with a female friend. They then undergo the preliminary marriage ritual (pasya) and exchange food. Then comes the marriage celebration itself (dawak/bayas)inclusive of the segep (which means to enter), pakde (sacrifice), betbet (butchering of pig for omens), playog/kolay (marriage ceremony proper), tebyag (merrymaking), mensupot (gift giving), sekat di tawid (giving of inheritance), and buka/inga, the end of the celebration. The married couple cannot separate once a child is born, and adultery is forbidden in their society as it is believed to bring misfortune and illness upon the adulterer.[11]

The Northern Kankana-eys have rich material culture among which is the four types of houses: the two-story innagamang, binang-iyan, tinokbob and the elevated tinabla. Other buildings include the granary (agamang), male clubhouse (dap-ay or abong), and female dormitory (ebgan). Their men wear rectangular woven cloths wrapped around their waist to cover the buttocks and the groin (wanes). The women wear native woven skirts (pingay or tapis) that cover their lower body from waist to knees and is held by a thick belt (bagket).[11]

Their household is sparsely furnished with only a bangkito/tokdowan, po-ok (small box for storage of rice and wine), clay pots, and sokong (carved bowl). Their baskets are made of woven rattan, bamboo or anes, and come in various shapes and sizes.[11]

The Kankana-eys have three main weapons, the bolo (gamig), the axe (wasay) and the spear (balbeg), which they previously used to kill with but now serve practical purposes in their livelihood. They also developed tools for more efficient ways of doing their work like the sagad (harrow), alado (plow dragged by carabao), sinowan, plus sanggap and kagitgit for digging. They also possess Chinese jars (gosi) and copper gongs (gangsa).[11]

For a living, the Northern Kankana-eys take part in barter and trade in kind, agriculture (usually on terraces), camote/sweet potato farming, slash-and-burn/swidden farming, hunting, fishing and food gathering, handicraft and other cottage industry. They have a simple political life, with the Dap-ay/abong being the center of all political, religious, and socials activities, with each dap-ay experiencing a certain degree of autonomy. The council of elders, known as the Amam-a, are a group of old, married men expert in custom law and lead in the decision-making for the village. They worship ancestors (anitos) and nature spirits.[11]

Southern Kankanaey

editThe Southern Kankanaey are one of the ethnolinguistic groups in the Cordillera. They live in the mountainous regions of Mountain Province and Benguet, more specifically in the municipalities of Tadian, Bauko, Sabangan, Bakun, Kibungan, Buguias and Mankayan.They are predominantly a nuclear family type (sinbe-ey,buma-ey, or sinpangabong), which are either patri-local or matri-local due to their bilateral kinship, composed of the husband, wife and their children. The kinship group of the Southern Kankana-eys consists of his descent group and, once he is married, his affinal kinsmen. Their society is divided into two social classes based primarily on the ownership of land: The rich (baknang) and the poor (abiteg or kodo). The baknang are the primary landowners to whom the abiteg render their services to. The Mankayan Kankana-eys, however, has no clear distinction between the baknang and the abiteg and all have equal access to resources such as the copper and gold mines.[12]

Contrary to popular belief, the Southern Kankana-eys do not worship idols and images. The carved images in their homes only serve decorative purposes. They believe in the existence of deities, the highest among which is Adikaila of the Skyworld whom they believe created all things. Next in the hierarchy is the Kabunyan, who are the gods and goddesses of the Skyworld, including their teachers Lumawig and Kabigat. They also believe in the spirits of ancestors (ap-apo or kakkading), and the earth spirits they call anito. They are very superstitious and believe that performing rituals and ceremonies help deter misfortunes and calamities. Some of these rituals are pedit (to bring good luck to newlyweds), pasang (cure sterility and sleeping sickness, particularly drowsiness) and pakde (cleanse community from death-causing evil spirits).[12]

The Southern Kankana-eys have a long process for courtship and marriage which starts when the man makes his intentions of marrying the woman known to her. Next is the sabangan, when the couple makes their wish to marry known to their family. The man offers firewood to the father of the woman, while the woman offers firewood to the man’s father. The parents then talk about the terms of the marriage, including the bride price to be paid by the man’s family. On the day of the marriage, the relatives of both parties offer gifts to the couple, and a pig is butchered to have its bile inspected for omens which would show if they should go on with the wedding. The wedding day for the Southern Kankana-eys is an occasion for merrymaking and usually lasts until the next day. Though married, the bride and groom are not allowed to consummate their marriage and must remain separated until such a time that they move to their own separate home.[12]

The Southern Kankana-eys have different types of houses among which are binang-iyan (box-like compartment on 4 posts 5 feet high), apa or inalpa (a temporary shelter smaller than bingang-iyan), inalteb (has a gabled roof and shorter eaves allowing for the installation of windows and other opening at the side), allao (a temporary built in the fields), at-ato or dap-ay (a clubhouse or dormitory for men, with a long, low gable-roofed structure with only a single door for entrance and exit), and ebgang or olog (equivalent to the at-ato, but for women). Men traditionally wear a loincloth (wanes) around the waist and between the legs which is tightened at the back. Both ends hang loose at the front and back to provide additional cover. Men also wear a woven blanket for an upper garment and sometimes a headband, usually colored red like the wanes. The women, on the other hand, wear a tapis, a skirt wrapped around to cover from the waist to the knees held together by a belt (bagket) or tucked in the upper edges usually color white with occasional dark blue color. As adornments, both men and women wear bead leglets, copper or shell earrings, and beads of copper coin. They also sport tattoos which serve as body ornaments and "garments".[12]

Southern Kankana-eys are economically involved in hunting and foraging (their chief livelihood), wet rice and swidden farming, fishing, animal domestication, trade, mining, weaving and pottery in their day-to-day activities to meet their needs. The leadership structure is largely based on land ownership, thus the more well-off control the community's resources. The village elders (lallakay/dakay or amam-a) who act as arbiters and jurors have the duty to settlements between conflicting members of the community, facilitate discussion among the villagers concerning the welfare of the community and lead in the observance of rituals. They also practice trial by ordeal. Native priests (mansip-ok, manbunong, and mankotom) supervise rituals, read omens, heal the sick, and remember genealogies.[12]

Gold and copper mining is abundant in Mankayan. Ore veins are excavated, then crushed using a large flat stone (gai-dan). The gold is separated using a water trough (sabak and dayasan), then melted into gold cakes.[12]

Musical instruments include the tubular drum (solibao), brass or copper gongs (gangsa), Jew's harp (piwpiw), nose flute (kalaleng), and a bamboo-wood guitar (agaldang).[12]

There is no more pure Southern Kankana-ey culture because of culture change that modified the customs and traditions of the people. The socio-cultural changes are largely due to a combination of factors which include the change in the local government system when the Spaniards came, the introduction of Christianity, the education system that widened the perspective of the individuals of the community, and the encounters with different people and ways of life through trade and commerce.[12]

Culture

editLike most ethnic groups, the Kankanaey built sloping terraces to maximize farm space in the rugged terrain of the Cordillera Administrative Region.

The Kankanaey differ in the way they dress. The soft-speaking Kankanaey women's dress has a color combination of black, white and red. The design of the upper attire is a criss-crossed style of black, white and red colors. The skirt or tapis is a combination of stripes of black, white and red.

The hard-speaking Kankanaey women's dress is composed of mainly red and black with a little white styles, as for the skirt or tapis which is mostly called bakget and gateng[clarification needed]. The men wear a woven loincloth known as wanes to the Kankanaeys of Besao and Sagada. The design of the wanes may vary according to social status or municipality.

The Kankanaey's major dances include tayaw, pattong and balangbang. The Tayaw is a community dance that is usually performed at weddings; it may be also danced by the Ibaloi people but has a different style. Pattong is also a community dance from Mountain Province which every municipality has its own style. Balangbang is the modern word for pattong. There are also some other dances that the Kankanaeys dance, such as the sakkuting, pinanyuan (wedding dance) and bogi-bogi (courtship dance). Kankanaey houses are built like the other Igorot houses, which reflect their social status.

Cuisine

editWet rice agriculture is the main economic activity of the Northern Kankanaey with some fields toiled twice a year while other only once due to too much water or no water at all. There are two varieties of rice called topeng which are planted in June and July and harvested in November and December, and ginolot which are planted in November and December and harvested in June and July. Northern kankana-eys also farm camote. Camote delicacies include (1) makimpit which are dried camotes, (2) boko which are camote sliced into thin pieces that could be steamed (sinalopsop) or cooked as in and sweetened with sugar (inab-abos-sang). These are good substitutes for rice that could be sliced into thin pieces and added to rice before cooking (kineykey) mixing the sweetness when the rice cooks. Squash, cucumber and other climbing vines are also planted. They also hunt and fish small fishes and eel which is a special delicacy when cooked. Crabs are also caught to make tengba, a gravy of pounded rice mixed with crabs, salted and placed in jars to age. This is common viand of every household and is eaten during childbirth.[11]

Although Southern Kankanaey also engage in wet rice agriculture, the chief means of livelihood is hunting and foraging. Wild animal meat such as deer, boar, civet cats and lizards are salted and dried under the sun to preserve it. Wild roots, honey and fruits are also gathered to supplement diet. Just like their northern counterparts, there are also two varieties of rice namely kintoman and saranay or bayag. The kintoman, just as mentioned earlier, is more popularly known as red rice due to its color. On the other hand, saranay is whitish and small grained. The usual types of fish caught are eel (dagit or igat) and small river fishes as well as crabs and other crustaceans. Pigs, chickens, dogs and cattle are domesticated as additional sources of food. Dog meat is considered as a delicacy and pigs and chickens are used mainly for ceremonial activities.[12]

A blood sausage known as pinuneg is eaten by the Kankanaey people.[14]

Funerary practices

editHanging coffins are one of the funerary practices among the Kankanaey people of Sagada, Mountain Province. They have not been studied by archaeologists, so the exact age of the coffins is unknown, though they are believed to be centuries old. The coffins are placed underneath natural overhangs, either on natural rock shelves/crevices or on projecting beams slotted into holes dug into the cliff-side. The coffins are small because the bodies inside the coffins are in a fetal position. This is due to the belief that people should leave the world in the same position as they entered it, a tradition common throughout the various pre-colonial cultures of the Philippines. The coffins are usually carved by their eventual occupants during their lifetimes.[15]

Despite their popularity, hanging coffins are not the main funerary practice of the Kankanaey. It is reserved only for distinguished or honorable leaders of the community. They must have performed acts of merit, made wise decisions, and led traditional rituals during their lifetimes. The height at which their coffins are placed reflects their social status. Most people interred in hanging coffins are the most prominent members of the amam-a, the council of male elders in the traditional dap-ay (the communal men's dormitory and civic center of the village). There is also one documented case of a woman being accorded the honor of a hanging coffin interment.[16]

The more common burial custom of the Kankanaey is for coffins to be tucked into crevices or stacked on top of each other inside limestone caves. Like in hanging coffins, the location depends on the status of the deceased as well as the cause of death. All of these burial customs require specific pre-interment rituals known as the sangadil. The Kankanaey believe that interring the dead in caves or cliffs ensures that their spirits (anito) can roam around and continue to protect the living.[17]

The Northern Kankana-eys honor their dead by keeping vigil and performing the rituals sangbo (offering of 2 pigs and 3 chickens), baya-o (singing of a dirge by three men), menbaya-o (elegy) and sedey (offering of pig). They finish off the burial ritual with dedeg (song of the dead), and then, the sons and grandsons carry the body to its resting place.[11] The funeral ritual of the Southern Kankana-eys lasts up to ten days, when the family honors their dead by chanting dirges and vigils and sacrificing a pig for each day of the vigil. Five days after the burial of the dead, those who participated in the burial take a bath in a river together, butcher a chicken, then offer a prayer to the soul of the dead.[12]

Tattoos

editAncient tattoos can be found among mummified remains of various Cordilleran peoples in cave and hanging coffin burials in northern Luzon, with the oldest surviving examples of which going back to the 13th century. The tattoos on the mummies are often highly individualized, covering the arms of female adults and the whole body of adult males. A 700 to 900-year-old Kankanaey mummy in particular, nicknamed "Apo Anno", had tattoos covering even the soles of the feet and the fingertips. The tattoo patterns are often also carved on the coffins containing the mummies.[18] Tattooing survived up until the mid-20th century, until modernization and conversion to Christianity finally made tattooing traditions extinct among the Kankanaey.[19][20]

Language

editIn intonation, there is a hard- (Applai) and soft-speaking Kankanaeys. Speakers of hard Kankanaey are from Sagada, Besao and the surrounding parts or barrios of the said municipalities. They speak Kankanaey with hard intonation and they differ in some words from the soft-speaking Kankanaey. The soft-speaking Kankanaeys come from Northern and some parts of Benguet and from the municipalities of Sabangan, Tadian and Bauko in Mountain Province. In words, for example, an Applai might say otik or beteg (pig) and the soft-speaking Kankanaey may say busaang or beteg as well. The Kankanaeys may also differ in some words like egay or aga, maid or maga. The Kankanaeys also speak Ilocano.

Religion

editImmortals

edit- Lumawig: the supreme deity; creator of the universe and preserver of life[21]

- Bugan: married to Lumawig[21]

- Bangan: the goddess of romance; a daughter of Bugan and Lumawig[21]

- Obban: the goddess of reproduction; a daughter of Bugan and Lumawig[21]

- Kabigat: one of the deities who contact mankind through spirits called anito and their ancestral spirits[21]

- Balitok: one of the deities who contact mankind through spirits called anito and their ancestral spirits[21]

- Wigan: one of the deities who contact mankind through spirits called anito and their ancestral spirits[21]

- Timugan: two brothers who took their sankah (handspades) and kayabang (baskets) and dug a hole into the lower world, Aduongan; interrupted by the deity Masaken; one of the two agreed to marry one of Masaken's daughters, but they both went back to earth when the found that the people of Aduongan were cannibals[22]

- Masaken: ruler of the underworld who interrupted the Timugan brothers[22]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Ethnicity in the Philippines (2020 Census of Population and Housing)". Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved July 4, 2023.

- ^ Fry, Howard (2006). A History of the Mountain Province (Revised ed.). Quezon City, Philippines: New Day Publishers. p. 22. ISBN 978-971-10-1161-1.

On the west side (of) the Bontok people . . . the Lepanto provincial area . . . (whose) population is somewhat mixed . . . but which I think is mainly Kankanai, who also people the northern part of Benguet . . . (and) the entire valley of the river Amburayan . . .

- ^ Jefrernovas, V; Perez, PL (2011). "Defining indigeneity representation and the indigenous people's rights act of 1997". Identity Politics in the Public Realm: Bringing Institutions Back In. UBC Press: 91.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "The Kankanaey People of the Philippines: History, Culture, Customs and Tradition [Indigenous People | Cordillera Ethnic Tribes]".

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20160424192103/http://sultankudaratprovince.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/SEP-2010_Sultan-Kudarat-Province.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "2010 Census of Population and Housing, Report No. 2A: Demographic and Housing Characteristics (Non-Sample Variables) - Philippines" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ Gibbons, Ann (2016-10-03). "'Game-changing' study suggests first Polynesians voyaged all the way from East Asia". www.sciencemag.org.

- ^ Weule, Genelle (2016-10-03). "DNA reveals earliest Pacific Islander ancestors came from Asia". ABC News - Science.

- ^ Skoglund, Pontus; Posth, Cosimo; Sirak, Kendra; et al. (2016). "Genomic insights into the peopling of the Southwest Pacific". Nature. 538 (7626): 510–513. Bibcode:2016Natur.538..510S. doi:10.1038/nature19844. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 5515717. PMID 27698418.

- ^ Mörseburg, Alexander; Pagani, Luca; Ricaut, Francois-Xavier; et al. (2016). "Multi-layered population structure in Island Southeast Asians". European Journal of Human Genetics. 24 (11): 1605–1611. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2016.60. PMC 5045871. PMID 27302840. S2CID 2682757.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). "7 The Northern Kankana-eys". Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. pp. 136–155. ISBN 9789711011093.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). "8 The Southern Kankana-eys". Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. pp. 156–175. ISBN 9789711011093.

- ^ Marche, Antoine-Alfred (1887). Luçon et Palaouan, six années de voyages aux Philippines. Paris: Librairie Hachette. pp. 153–155.

- ^ "Baguio eats: Head to this restaurant for a literal taste of blood". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- ^ Panchal, Jenny H.; Cimacio, Maria Beatriz (2016). "Culture Shock – A Study of Domestic Tourists in Sagada, Philippines" (PDF). 4th Interdisciplinary Tourism Research Conference: 334–338.

- ^ Comila, Felipe S. (2007). "The Disappearing Dap-ay: Coping with Change in Sagada". In Arquiza, Yasmin D. (ed.). The Road to Empowerment: Strengthening the Indigenous Peoples Rights Act (PDF). Vol. 2: Nurturing the earth, nurturing life. International Labour Organization. pp. 1–16.

- ^ Macatulad, JB; Macatulad, Renée (5 February 2015). "The Hanging Coffins of Echo Valley, Sagada, Mountain Province". Will Fly For Food. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ Salvador-Amores, Analyn (2012). "The Recontextualization of Burik (Traditional Tattoos) of Kabayan Mummies in Benguet to Contemporary Practices". Humanities Diliman. 9 (1): 74–94.

- ^ Salvador-Amores, Analyn. "Burik: Tattoos of the Ibaloy Mummies of Benguet, North Luzon, Philippines". Ancient Ink: The Archaeology of Tattooing. University of Washington Press, Seattle, Washington: 37–55.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Salvador-Amores, Analyn (June 2011). "Batok (Traditional Tattoos) in Diaspora: The Reinvention of a Globally Mediated Kalinga Identity". South East Asia Research. 19 (2): 293–318. doi:10.5367/sear.2011.0045. S2CID 146925862.

- ^ a b c d e f g Jocano, F. L. (1969). Philippine Mythology. Quezon City: Capitol Publishing House Inc.

- ^ a b Wilson, L. L. (1947). Apayao Life and Legends. Baugio City: Private.

External links

edit- Media related to Kankanaey people at Wikimedia Commons