The Convention of Kanagawa, also known as the Kanagawa Treaty (神奈川条約, Kanagawa Jōyaku) or the Japan–US Treaty of Peace and Amity (日米和親条約, Nichibei Washin Jōyaku), was a treaty signed between the United States and the Tokugawa Shogunate on March 31, 1854. Signed under threat of force,[2] it effectively meant the end of Japan's 220-year-old policy of national seclusion (sakoku) by opening the ports of Shimoda and Hakodate to American vessels.[3] It also ensured the safety of American castaways and established the position of an American consul in Japan. The treaty precipitated the signing of similar treaties establishing diplomatic relations with other Western powers.

| Japan–US Treaty of Peace and Amity | |

|---|---|

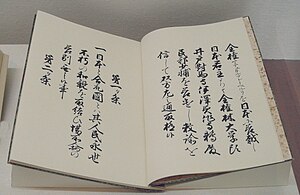

Japanese copy of the Convention of Kanagawa, ratified February 21, 1855 | |

| Signed | 31 March 1854 |

| Location | Yokohama, Japan |

| Sealed | March 31, 1854 |

| Effective | September 30, 1855 |

| Condition | Ratification by US Congress, signing by President Franklin Pierce and signing by Emperor Kōmei[1] |

| Signatories | |

| Depositary | Diplomatic Record Office of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Japan) |

| Languages | |

| Full text | |

Isolation of Japan

editSince the beginning of the 17th century, the Tokugawa Shogunate pursued a policy of isolating the country from outside influences. Foreign trade was maintained only with the Dutch and the Chinese and was conducted exclusively at Nagasaki under a strict government monopoly. This "Pax Tokugawa" period is largely associated with domestic peace, social stability, commercial development, and expanded literacy.[4] This policy had two main objectives:

- To suppress the spread of Christianity. By the early 17th century, Catholicism had spread throughout the world. Tokugawa feared that trade with western powers would cause further instability in the nation. Thus, the isolation policy expelled foreigners and did not allow international travel.[5][6]

- The Japanese feared that foreign trade and the wealth developed would lead to the rise of a daimyō powerful enough to overthrow the ruling Tokugawa clan, especially after seeing what happened to China during the Opium Wars.[7][4]

By the early 19th century, this policy of isolation was increasingly under challenge. In 1844, King William II of the Netherlands sent a letter urging Japan to end the isolation policy on its own before change would be forced from the outside. In 1846, an official American expedition led by Commodore James Biddle arrived in Japan asking for ports to be opened for trade but was sent away.[8]

Perry expedition

editIn 1853, United States Navy Commodore Matthew C. Perry was sent with a fleet of warships by U.S. President Millard Fillmore to force the opening of Japanese ports to American trade,[9] through the use of gunboat diplomacy if necessary. President Fillmore's letter shows the U.S. sought trade with Japan to open export markets for American goods like gold from California, enable U.S. ships to refuel in Japanese ports, and secure protections and humane treatment for any American sailors shipwrecked on Japan's shores.[10] The growing commerce between America and China, the presence of American whalers in waters offshore Japan, and the increasing monopolization of potential coaling stations by the British and French in Asia were all contributing factors. The Americans were also driven by concepts of manifest destiny and the desire to impose the perceived benefits of western civilization and Christianity on what they perceived as backward Asian nations.[11] From the Japanese perspective, increasing contacts with foreign warships and the increasing disparity between western military technology and the Japanese feudal armies fostered growing concern. The Japanese had been keeping abreast of world events via information gathered from Dutch traders in Dejima and had been forewarned by the Dutch of Perry's voyage.[11] There was a considerable internal debate in Japan on how best to meet this potential threat to Japan's economic and political sovereignty in light of events occurring in China with the Opium Wars.

Perry arrived with four warships at Uraga, at the mouth of Edo Bay on July 8, 1853. He blatantly refused Japanese demands that he proceed to Nagasaki, which was the designated port for foreign contact. After threatening to continue directly on to Edo, the nation's capital, and to burn it to the ground if necessary, he was allowed to land at nearby Kurihama on July 14 and to deliver his letter.[12] Such refusal was intentional, as Perry wrote in his journal: “To show these princes how little I regarded their order for me to depart, on getting on board I immediately ordered the whole squadron underway, not to leave the bay… but to go higher up… would produce a decided influence upon the pride and conceit of the government, and cause a more favorable consideration of the President’s letter."[3] Perry's power front did not stop with refusing to land in Uraga, but he continued to push the boundaries of the Japanese. He ordered the squadron to survey Edo bay, which led to a stand-off between Japanese officers with swords and Americans with guns. By firing the guns into the water, Perry demonstrated their military might, which greatly affected Japanese perceptions of Perry and the United States. Namely, a perception of fear and disrespect.[13]

Despite years of debate on the isolation policy, Perry's letter created great controversy within the highest levels of the Tokugawa shogunate. The shōgun himself, Tokugawa Ieyoshi, died days after Perry's departure and was succeeded by his sickly young son, Tokugawa Iesada, leaving effective administration in the hands of the Council of Elders (rōjū) led by Abe Masahiro. Abe felt that it was impossible for Japan to resist the American demands by military force and yet was reluctant to take any action on his own authority for such an unprecedented situation. Attempting to legitimize any decision taken, Abe polled all of the daimyō for their opinions. This was the first time that the Tokugawa shogunate had allowed its decision-making to be a matter of public debate and had the unforeseen consequence of portraying the shogunate as weak and indecisive.[14] The results of the poll also failed to provide Abe with an answer; of the 61 known responses, 19 were in favour of accepting the American demands and 19 were equally opposed. Of the remainder, 14 gave vague responses expressing concern of possible war, 7 suggested making temporary concessions and 2 advised that they would simply go along with whatever was decided.[15]

Perry returned again on February 11, 1854, with an even larger force of eight warships and made it clear that he would not be leaving until a treaty was signed. Perry continued his manipulation of the setting, such as keeping himself aloof from lower-ranking officials, implying the use of force, surveying the harbor, and refusing to meet in the designated negotiation sites. Negotiations began on March 8 and proceeded for around one month. Each party shared a performance when Perry arrived. The Americans had a technology demonstration, and the Japanese had a sumo wrestling show.[16] While the new technology awed the Japanese people, Perry was unimpressed by the sumo wrestlers and perceived such performance as foolish and degrading: “This disgusting exhibition did not terminate until the whole twenty-five had, successively, in pairs, displayed their immense powers and savage qualities."[3] The Japanese side gave in to almost all of Perry's demands, with the exception of a commercial agreement modelled after previous American treaties with China, which Perry agreed to defer to a later time. The main controversy centered on the selection of the ports to open, with Perry adamantly rejecting Nagasaki.

The treaty, written in English, Dutch, Chinese and Japanese, was signed on March 31, 1854, at what is now Kaikō Hiroba (Port Opening Square) Yokohama, a site adjacent to the current Yokohama Archives of History.[15] The celebratory events for the signing ceremony included a Kabuki play from the Japanese side and, from the American side, U.S. military band music and blackface minstrelsy.[17]: 32–33

Treaty of Peace and Amity (1854)

editThe "Japan-US Treaty of Peace and Amity" has twelve articles:

| Article | Summary |

|---|---|

| § I | Mutual peace between the United States and the Empire of Japan |

| § II | Opening of the ports of Shimoda & Hakodate |

| § III | Assistance to be provided to shipwrecked American sailors |

| § IV | Shipwrecked sailors not to be imprisoned or mistreated |

| § V | Freedom of movement for temporary foreign residents in treaty ports (with limitations)[18] |

| § VI | Trade transactions to be permitted |

| § VII | Currency exchange to facilitate any trade transactions to be allowed |

| § VIII | Provisioning of American ships to be a Japanese government monopoly |

| § IX | Japan to give the United States any favourable advantages which might be negotiated by Japan with any other foreign government in the future |

| § X | Forbidding the United States from using any other ports aside from Shimoda and Hakodate |

| § XI | Opening of an American consulate at Shimoda |

| § XII | Treaty to be ratified within 18 months of signing |

At the time, shōgun Tokugawa Iesada was the de facto ruler of Japan; for the Emperor of Japan to interact in any way with foreigners was out of the question. Perry concluded the treaty with representatives of the shogun, led by plenipotentiary Hayashi Akira (林韑) and the text was endorsed subsequently, albeit reluctantly, by Emperor Kōmei.[19] The treaty was ratified on February 21, 1855.[20]

Consequences of the treaty

editIn the short term, the U.S. was content with the agreement since Perry had achieved his primary objective of breaking Japan's sakoku policy and setting the grounds for protection of American citizens and an eventual commercial agreement. On the other hand, the Japanese were forced into this trade, and many saw it as a sign of weakness. The Tokugawa shogunate could point out that the treaty was not actually signed by the shogun, or indeed any of his rōjū, and that it had at least temporarily averted the possibility of immediate military confrontation.[21]

Externally, the treaty led to the United States-Japan Treaty of Amity and Commerce, the "Harris Treaty" of 1858, which allowed the establishment of foreign concessions, extraterritoriality for foreigners, and minimal import taxes for foreign goods. The Japanese chafed under the "unequal treaty system" which characterized Asian and western relations during this period.[22] The Kanagawa treaty was also followed by similar agreements with the United Kingdom (Anglo-Japanese Friendship Treaty, October 1854), Russia (Treaty of Shimoda, February 7, 1855), and France (Treaty of Amity and Commerce between France and Japan, October 9, 1858).

Internally, the treaty had far-reaching consequences. Decisions to suspend previous restrictions on military activities led to re-armament by many domains and further weakened the position of the shogun.[23] Debate over foreign policy and popular outrage over perceived appeasement to the foreign powers was a catalyst for the sonnō jōi movement and a shift in political power from Edo back to the Imperial Court in Kyoto. The opposition of Emperor Kōmei to the treaties further lent support to the tōbaku (overthrow the shogunate) movement, and eventually to the Meiji Restoration, which affected all realms of Japanese life. Following this period came an increase in foreign trade, the rise of Japanese military might, and the later rise of Japanese economic and technological advancement. Westernization at the time was a defense mechanism, but Japan has since found a balance between Western modernity and Japanese tradition.[24]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Miller, Bonnie M. (2021). "Commodore Perry and the Opening of Japan". Bill of Rights Institute. Retrieved 2022-07-06.

- ^ "Despatchers from U.S. Consuls in Kanagawa, Japan, 1861–1897". Gale Primary Sources, Nineteenth Century Collections Online. December 26, 1861. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- ^ a b c Perry

- ^ a b J. Green, "Samurai, Daimyo, Matthew Perry, and Nationalism: Crash Course World History #34. CrashCourse, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nosq94oCl_M

- ^ P. Duus, Modern Japan, ch. 4

- ^ A. T. Embree & C. Gluck, Asia in Western and World History: A guide for teaching

- ^ Beasley, pp. 74–77

- ^ Beasley, p. 78

- ^ Millard Fillmore, President of the United States of America (November 13, 1852). "Letters from U.S. President Millard Fillmore and U.S. Navy Commodore Matthew C. Perry to the Emperor of Japan (1852–1853)" (PDF). Columbia University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2010-06-22. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- ^ Hall, p. 207.

- ^ a b Beasley, p. 88.

- ^ Beasley, p. 89.

- ^ Kitahara, M. (1986), pp. 53–65

- ^ Hall, p. 211.

- ^ a b Beasley, pp. 90–95.

- ^ Kitahara (1986), pp. 53–65.

- ^ Driscoll, Mark W. (2020). The Whites are Enemies of Heaven: Climate Caucasianism and Asian Ecological Protection. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-1-4780-1121-7.

- ^ "From Washington; The Japanese Treaty-Its Advantages and Disadvantages-The President and Col. Rinney, &c.," New York Times. October 18, 1855.

- ^ Cullen, pp. 173–185.

- ^ Diplomatic Record Office of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Japan) exhibit.

- ^ Beasley, pp. 96–97

- ^ Edstrom p. 101.

- ^ Hall, pp. 211–213.

- ^ Kitahara (1983), pp. 103–110.

References

edit- Arnold, Bruce Makoto (2005). Diplomacy Far Removed: A Reinterpretation of the U.S. Decision to Open Diplomatic Relations with Japan (Thesis). University of Arizona. [1]

- Auslin, Michael R., Negotiating with Imperialism: The Unequal Treaties and the Culture of Japanese Diplomacy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-674-01521-0; OCLC 56493769

- Beasley, William G (1972). The Meiji Restoration. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0804708159.

- Cullen, L. M., A History of Japan, 1582–1941: Internal and External Worlds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-521-52918-2

- Edström, Bert, The Japanese and Europe: Images and Perceptions. London: Routledge, 2000. ISBN 978-1-873410-86-8

- Hall, John Whitney (1991). Japan: From Prehistory to Modern Times. University of Michigan. ISBN 978-0939512546.

- Kitahara, M., "Popular Culture in Japan: A Psychoanalytic Interpretation," The Journal of Popular Culture, XVII, 1983.

- Kitahara, Michio (March 1986). "Commodore Perry and the Japanese: A Study in the Dramaturgy of Power". Symbolic Interaction. 9 (1): 53–65. doi:10.1525/si.1986.9.1.53. ISSN 0195-6086.

- Perry, Matthew Calbraith, Narrative of the expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan, 1856. Archived 2017-05-19 at the Wayback Machine New York: D. Appleton and Company. 1856. Digitized by University of Hong Kong Libraries, Digital Initiatives, "China Through Western Eyes."

- Taylor, Bayard, A visit to India, China, and Japan in the year 1853 Archived 2016-03-11 at the Wayback Machine New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1855. Digitized by University of Hong Kong Libraries, Digital Initiatives, "China Through Western Eyes".