This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (December 2020) |

Junius Richard Jayewardene (Sinhala: ජුනියස් රිචඩ් ජයවර්ධන; Tamil: ஜூனியஸ் ரிச்சட் ஜயவர்தனா; 17 September 1906 – 1 November 1996), commonly abbreviated in Sri Lanka as J.R., was a Sri Lankan lawyer, public official and statesman who served as Prime Minister of Sri Lanka from 1977 to 1978 and as the second President of Sri Lanka from 1978 to 1989. He was a leader of the nationalist movement in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) who served in a variety of cabinet positions in the decades following independence. A longtime member of the United National Party, he led it to a landslide victory in the 1977 parliamentary elections and served as prime minister for half a year before becoming the country's first executive president under an amended constitution.[1]

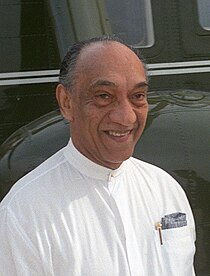

J. R. Jayewardene | |

|---|---|

Jayewardene in 1984 | |

| 2nd President of Sri Lanka | |

| In office 4 February 1978 – 2 January 1989 | |

| Prime Minister | Ranasinghe Premadasa |

| Preceded by | William Gopallawa |

| Succeeded by | Ranasinghe Premadasa |

| 7th Prime Minister of Sri Lanka | |

| In office 23 July 1977 – 4 February 1978 | |

| President | William Gopallawa |

| Preceded by | Sirimavo Bandaranaike |

| Succeeded by | Ranasinghe Premadasa |

| 6th Leader of the Opposition | |

| In office 7 June 1970 – 18 May 1977 | |

| Prime Minister | Sirimavo Bandaranaike |

| Preceded by | Sirimavo Bandaranaike |

| Succeeded by | A. Amirthalingam |

| 6th Secretary General of Non-Aligned Movement | |

| In office 4 February 1978 – 9 September 1979 | |

| Preceded by | William Gopallawa |

| Succeeded by | Fidel Castro |

| Minister of Finance | |

| In office 24 April 1960 – 20 July 1960 | |

| Prime Minister | Dudley Senanayake |

| Preceded by | Oliver Ernest Goonetilleke |

| Succeeded by | Stanley de Zoysa |

| In office 26 September 1947 – 13 October 1953 | |

| Prime Minister |

|

| Succeeded by | Oliver Ernest Goonetilleke |

| Member of Parliament for Colombo West | |

| In office 4 August 1977 – 4 February 1978 | |

| Preceded by | Constituency created |

| Succeeded by | Anura Bastian |

| Member of Parliament for Colombo South | |

| In office 5 August 1960 – 18 May 1977 | |

| Preceded by | Edmund Samarawickrema |

| Succeeded by | Constituency abolished |

| Member of the Ceylonese Parliament for Kelaniya | |

| In office 30 March 1960 – 23 April 1960 | |

| Preceded by | R.G. Senanayake |

| Succeeded by | R.S. Perera |

| In office 14 October 1947 – 18 February 1956 | |

| Preceded by | Constituency created |

| Succeeded by | R.G. Senanayake |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Junius Richard Jayewardene 17 September 1906 Colombo, British Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) |

| Died | 1 November 1996 (aged 90) Colombo, Sri Lanka |

| Political party | United National Party |

| Spouse | |

| Children | Ravi Jayewardene (Son) |

| Parents |

|

| Residence | Braemar |

| Alma mater | |

| Profession | Advocate |

| Signature | |

A controversial figure in the history of Sri Lanka, while the open economic system he introduced in 1978 brought the country out of the economic turmoil Sri Lanka was facing as the result of the preceding closed economic policies,[2] Jayawardene's actions, including his response to the Black July riots of 1983, have been accused of contributing to the beginnings of the Sri Lankan Civil War.[3]

Early life and marriage

editChildhood

editBorn in Colombo to the prominent Jayewardene family with a strong association with the legal profession, Jayewardene was the eldest of twelve children, of Hon. Justice Eugene Wilfred Jayewardene KC, a prominent lawyer and Agnes Helen Don Philip Wijewardena daughter of Muhandiram Tudugalage Don Philip Wijewardena a wealthy timber merchant. He was known as Dickie within his family. His younger brothers included Hector Wilfred Jayewardene, QC and Rolly Jayewardene, FRCP. His uncles were the Colonel Theodore Jayewardene, Justice Valentine Jayewardene and the Press Baron D. R. Wijewardena. Raised by an English nanny,[4] he received his primary education at Bishop's College, Colombo.

Education and early career

editJayewardene gained admission to Royal College, Colombo for his secondary education. There he excelled in sports, played for the college cricket team, debuting in the Royal-Thomian series in 1925; captained the rugby team in 1924 at the annual "Royal-Trinity Encounter" (which later became known as the Bradby Shield Encounter); he was the vice captain of the football team in 1924; and was a member of the boxing team winning sports colours. He was a Senior Cadet; Captain, Debating Team; Editor, College Magazine; first Secretary in Royal College Social Services League in 1921 and he became the head prefect in 1925. In later life, he served as president, Board of Control for Cricket in Sri Lanka; President, Sinhalese Sports Club; and Secretary, Royal College Union.[5][6]

Following the family tradition, Jayewardene entered the University College, Colombo in 1926 pursuing the Advocate's course, reading English, Latin, Logic and Economics for two years, after which he entered Ceylon Law College in 1928. He formed the College Union based on that of the Oxford Union with assistance of S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike who had recently returned to Ceylon. At the Ceylon Law College he won the Hector Jayewardene Gold Medal and the Walter Pereira Prize in 1929. During this time he worked as his father's Private Secretary, while latter served as a Puisne Justice of Supreme Court of Ceylon and in July 1929, he joined three others in forming a dining club they called The Honorable Society of Pushcannons, which was later renamed as the Priya Sangamaya. In 1931, he passed his advocates exams, starting his legal practice in the unofficial bar.

Marriage

editOn 28 February 1935, Jayewardene married the heiress Elina Bandara Rupasinghe, only daughter of Nancy Margaret Suriyabandara and Gilbert Leonard Rupasinghe, a notary public turned successful businessmen. Their only child Ravindra "Ravi" Vimal Jayewardene was born the year after.[7] Having originally settled at Jayewardene's parents house, Vaijantha, the Jayewardenes moved to their own house Braemar in 1938, where they remained the rest of their lives, when not holidaying at their holiday home in Mirissa.[8][9]

Early political career

editJayewardene was attracted to national politics in his student years and developed strong nationalist views. He converted from Anglicanism to Buddhism and adopted the national dress as his formal attire.[10][5][11][12]

Jayewardene did not practice law for long. In 1943 he gave up his full time legal practice to become an activist in the Ceylon National Congress (CNC), which provided the organizational platform for Ceylon's nationalist movement (the island was officially renamed Sri Lanka in 1972).[13] He became its Joint Secretary with Dudley Senanayake in 1939 and in 1940 he was elected to the Colombo Municipal Council from the New Bazaar Ward.

State Council

editHe was elected to the colonial legislature, the State Council in 1943 by winning the Kelaniya by-election following the resignation of incumbent D. B. Jayatilaka. His victory is credited to his use of an anti-Christian campaign against his opponent the nationalist E. W. Perera.[14] During World War II, Jayewardene, along with other nationalists, contacted the Japanese and discussed a rebellion to drive the British from the island. In 1944, Jayewardene moved a motion in the State Council that Sinhala alone should replace English as the official language.[15]

First finance minister of Ceylon

editAfter joining the United National Party on its formation in 1946 as a founder member, he was reelected from the Kelaniya electorate in the 1st parliamentary election and was appointed by D. S. Senanayake as the Minister of Finance in the island's first Cabinet in 1947. Initiating post-independence reforms, he was instrumental in the establishment of the Central Bank of Ceylon under the guidance of the American economist John Exter. In 1951 Jayewardene was a member of the committee to select a National Anthem for Sri Lanka headed by Sir Edwin Wijeyeratne. The following year he was elected as the President of the Board of Control for Cricket in Ceylon. He played a major role in re-admitting[16] Japan to the world community at the San Francisco Conference. Jayewardene struggled to balance the budget, faced with mounting government expenditures, particularly for rice subsidies. He was re-elected in 1952 parliamentary election and remained as finance minister.

Minister of agriculture and food

editHis 1953 proposal to cut the subsidies on which many poor people depended on for survival provoked fierce opposition and the 1953 Hartal campaign, and had to be called off. Following the resignation of Prime Minister Dudley Senanayake after the 1953 Hartal, the new Prime Minister Sir John Kotelawala appointed Jayewardene as minister of agriculture and food and leader of the house.

Defeat and opposition

editPrime Minister Sir John Kotelawala called for early elections in 1956 with confidence that the United National Party would win the election. The 1956 parliamentary election saw the United National Party suffering a crushing defeat at the hands of the socialist and nationalist coalition led by the Sri Lanka Freedom Party headed by S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike. Jayewardene himself lost his parliamentary seat in Kelaniya to R. G. Senanayake, who had contested both his own constituency Dambadeniya and Jayewardene's constituency of Kelaniya with the objective of defeating the latter after he had forced Senanayake out of the party.

Having lost his seat in parliament, Jayewardene pushed the party to accommodate nationalism and endorse the Sinhala Only Act, which was bitterly opposed by the island's minorities. When Bandaranaike came to an agreement with S.J.V. Chelvanayagam in 1957, to solve the outstanding problems of the minorities, Jayawardene led a "March on Kandy" against it, but was stopped at Imbulgoda S. D. Bandaranayake.[14] The U.N.P.'s official organ the Siyarata subsequently ran several anti-Tamil articles, including a poem, containing an exhortation to kill Tamils in almost every line.[17] Throughout the 1960s Jayewardene clashed over this issue with party leader Dudley Senanayake. Jayewardene felt the UNP should be willing to play the ethnic card, even if it meant losing the support of ethnic minorities.

Minister of finance

editJayewardene became the vice-president and chief organizer of the United National Party, which achieved a narrow win in the March 1960 parliamentary election, forming a government under Dudley Senanayake. Jayewardene having been elected to parliament once again from the Kelaniya electorate was appointed once again as minister of finance. The government lasted only three months and lost the July 1960 parliamentary election to the a new coalition led by Bandaranayake's widow. Jayewardene remained in parliament in the opposition having been elected from the Colombo South electorate.[18]

Minister of state

editThe United National Party won the next election in 1965 and formed a national government with the Sri Lanka Freedom Socialist Party led by C. P. de Silva. Jayewardene was reelected from the Colombo South electorate uncontested and was appointed Chief Government Whip. Senanayake appointed Jayewardene to his cabinet as Minister of State and Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of Defence and External Affairs thereby becoming the de facto deputy prime minister. No government had given serious thought to the development of the tourism industry as an economically viable venture until the United National Party came to power in 1965 and the subject came under the purview of J. R. Jayewardene. Jayewardene saw tourism as a great industry capable of earning foreign exchange, providing avenues of mass employment, and creating a workforce which commanded high employment potential globally. He was determined to place this industry on a solid foundation, providing it a 'conceptional base and institutional support.' This was necessary to bring dynamism and cohesiveness into an industry, shunned by leaders in the past, ignored by investors who were inhibited by the lack of incentive to invest in projects which were uncertain of a satisfactory return. Jayewardene considered it essential for the government to give that assurance and with this objective in view he tabled the Ceylon Tourist Board Act No 10 of 1966 followed by Ceylon Hotels Corporation Act No 14 of 1966. At present the tourism industry in Sri Lanka is major foreign exchange earner with tourist resorts in almost all cities and an annual turnover of over 500,000 tourists are enjoying the tropical climes and beaches.[19][20]

Leader of the opposition

editIn the general election of 1970 the UNP suffered a major defeat, when the SLFP and its newly formed coalition of leftist parties won almost 2/3 of the parliamentary seats. Once again elected to parliament J. R. Jayewardene took over as opposition leader and de facto leader of the UNP due to the ill health of Dudley Senanayake. After Senanayake's death in 1973, Jayewardene succeeded him as UNP leader. He gave the SLFP government his fullest support during the 1971 JVP Insurrection (even though his son was arrested by the police without charges) and in 1972 when the new constitution was enacted proclaiming Ceylon a republic. However he opposed the government in many moves, which he saw as short sighted and damaging for the country's economy in the long run. These included the adaptation of the closed economy and nationalization of many private business and lands. In 1976 he resigned from his seat in parliament in protest, when the government used its large majority in parliament to extend the duration of the government by two more years at the end of its six-year term without holding a general election or a referendum requesting public approval.

Prime minister

editTapping into growing anger with the SLFP government, Jayewardene led the UNP to a crushing victory in the 1977 election. The UNP won a staggering five-sixths of the seats in parliament—a total that was magnified by the first-past-the-post system, and one of the most lopsided victories ever recorded for a democratic election. Having been elected to parliament from the Colombo West Electoral District, Jayewardene became Prime Minister and formed a new government.

Presidency

editShortly thereafter, he amended the constitution of 1972 to make the presidency an executive post. The provisions of the amendment automatically made the incumbent prime minister—himself—president, and he was sworn in as president on 4 February 1978. He passed a new constitution on 31 August 1978 which came into operation on 7 September of the same year, which granted the president sweeping—and according to some critics, almost dictatorial—powers. He moved the legislative capital from Colombo to Sri Jayawardanapura Kotte. He had likely SLFP presidential nominee Sirimavo Bandaranaike stripped of her civic rights and barred from running for office for six years, based her decision in 1976 to extend the term of parliament. This ensured that the SLFP would be unable to field a strong candidate against him in the 1982 election, leaving his path to victory clear. This election was held under the 3rd amendment to the constitution which empowered the president to hold a Presidential Election anytime after the expiration of four years of his first term. He held a referendum to cancel the 1983 parliamentary elections, and allow the 1977 parliament to continue until 1989. He also passed a constitutional amendment barring from Parliament any MP who supported separatism; this effectively eliminated the main opposition party, the Tamil United Liberation Front.

Economy

editThere was a complete turnaround in economic policy under him as the previous policies had led to economic stagnation. He opened the heavily state-controlled economy to market forces, which many credit with subsequent economic growth. He opened up the economy and introduced more liberal economic policies emphasizing private sector led development. Policies were changed to create an environment conducive to foreign and local investment, with the objective of promoting export led growth shifting from previous policies of import substitution. To facilitate export oriented enterprises and to administer Export Processing Zones the Greater Colombo Economic Commission was established. Food subsidies were curtailed and targeted through a Food Stamps Scheme extended to the poor. The system of rice rationing was abolished. The Floor Price Scheme and the Fertilizer Subsidy Scheme were withdrawn. New welfare schemes, such as free school books and the Mahapola Scholarship Programme, were introduced. The rural credit programme expanded with the introduction of the New Comprehensive Rural Credit Scheme and several other medium and long-term credit schemes aimed at small farmers and the self-employed.[21]

He also launched large scale infrastructure development projects. He launched an extensive housing development program to meet housing shortages in urban and rural areas. The Accelerated Mahaweli Programme built new reservoirs and large hydropower projects such as the Kotmale, Victoria, Randenigala, Rantembe and Ulhitiya. Several Trans Basin Canals were also built to divert water to the Dry Zone.[21]

Conservation

editHis administration launched several wildlife conservation initiatives. This included stopping commercial logging in rain forests such as Sinharaja Forest Reserve which was designated a World Biosphere Reserve in 1978 and a World Heritage Site in 1988.

Tamil militancy and civil war

editJayewardene moved to crack down on the growing activity of Tamil militant groups active since the mid-1970s. He passed the Prevention of Terrorism Act in 1979, giving police sweeping powers to arrest and detain. This only escalated the ethnic tensions. Jayewardene claimed he needed overwhelming power to deal with the militants. After the 1977 riots, the government made one concession to the Tamils; it lifted the policy of standardization for university admission that had driven many Tamil youths into militancy. The concession was regarded by the militants as too little and too late, and violent attacks continued, culminating in the ambush of Four Four Bravo which led to the Black July riots. Black July riots transformed the militancy into a civil war, with the swelling of ranks of the militant groups. By 1987, the LTTE had emerged as the dominant of the Tamil militant groups and had a free hand over the Jaffna Peninsula, limiting government activities in that region. Jayewardene's administration responded with a massive military operation codenamed Operation Liberation to eliminate the LTTE leadership. Jayewardene had to halt the offensive after pressure from India pushed for a negotiated solution to the conflict after executing Operation Poomalai. Jayewardene and Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi finally concluded the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord, which provided for devolution of powers to Tamil dominated regions, an Indian peacekeeping force in the north, and the demobilization of the LTTE.

The LTTE rejected the accord, as it fell short of even an autonomous state. The provincial councils suggested by India did not have powers to control revenue, policing, or government-sponsored Sinhala settlements in Tamil provinces. Sinhala nationalists were outraged by both the devolution and the presence of foreign troops on Sri Lankan soil. An attempt was made on Jayewardene's life in 1987 as a result of his signing of the accord. Young, deprived Sinhalese soon rose in a revolt, organized by the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) which was eventually put down by the government by 1989.

Foreign policy

editIn contrast with his predecessor, Sirimavo Bandaranaike, Jayewardena's foreign policy was aligned with American policies (earning him the nickname 'Yankie Dickie') much to the chagrin of India. Before Jayewardena's ascendency into the presidency, Sri Lanka had doors widely open to neighboring India. Jayewardena's tenure in the office restricted the doors to India a number of times; once an American company tender was granted over an Indian company tender.

Jayewardene hosted Queen Elizabeth II in a visit to Sri Lanka in October 1981.

In 1984, Jayewardene made an official State visit the United States; first Sri Lankan President to do so, upon the invitation of then US President Ronald Reagan.

Post-presidency

editJayewardene left office and retired from politics in 1989 after the conclusion of his second term as president at the age of 82;[22] after his successor Ranasinghe Premadasa was formally inaugurated on 2 January 1989. He did not re-enter politics during his retirement even after the assassination of Premadasa in 1993.

Death

editJayewardene died of colon cancer, on 1 November 1996, aged 90, at a hospital in Colombo.[23] He was survived by his wife, Elina, and his son, Ravi.[24]

Legacy

editOn the economic front, Jayewardene's legacy is decisively a positive one.[21] His economic policies are often credited with saving the Sri Lankan economy from ruin.[2] For thirty years after independence, Sri Lanka had struggled in vain with slow growth and high unemployment. By opening up the country for extensive foreign investments, lifting price controls and promoting private enterprise (which had taken a heavy hit because of the policies of the preceding administration), Jayewardene ensured that the island maintained healthy growth despite the civil war. William K. Steven of The New York Times observes, "President Jayawardene's economic policies were credited with transforming the economy from one of scarcity to one of abundance."[2][25]

On the ethnic question, Jayewardene's legacy is bitterly divisive. When he took office, ethnic tensions were present in the country but were not overtly volatile. But relations between the two ethnicities heavily deteriorated during his administration and his response to these tensions and the signs of conflict has been heavily criticized.[3][4] President Jayewardene saw these differences between the Sinhalese and Tamils as being ''an unbridgeable gap''.[25] Jayewardene said in an interview with the Daily Telegraph, 11 July 1983, "Really, if I starve the Tamils out, the Sinhala people will be happy"[26][27][28][29] in reference to the widespread anti-Tamil sentiments among the Sinhalese at that time.[25]

Highly respected in Japan for his call for peace and reconciliation with post-war Japan at the Peace Conference in San Francisco in 1951, a statue of Jayewardene was erected at the Kamakura Temple in the Kanagawa Prefecture in Japan in his honor.[30]

J.R. Jayewardene Centre

editIn 1988, the J.R. Jayewardene Centre was established by the J.R. Jayewardene Centre Act No. 77 of 1988 by Parliament at the childhood home of J. R. Jayewardene Dharmapala Mawatha, Colombo. It serves as archive for J.R. Jayewardene's personal library and papers as well as papers, records from the Presidential Secretariat and gifts he received in his tenure as president.

Further reading

edit- De Silva, K. M., & Wriggins, W. H. (1988), J.R. Jayewardene of Sri Lanka: a political biography, University of Hawaii Press ISBN 0-8248-1183-6

- Jayewardene, J. R. (1988), My quest for peace: a collection of speeches on international affairs, OCLC 20515117

- Dissanayaka, T. D. S. A. (1977), J.R. Jayewardene of Sri Lanka: the inside story of how the Prime Minister led the UNP to victory in 1977, Swastika Press OCLC 4497112

- S. Venkatnarayan (30 April 1984). "We can look after ourselves: Sri Lankan President Jayewardene". India Today.

- S.H. Venkatramani; Prabhu Chawla (15 December 1985). "India cannot support violence whatever the cause may be: J.R. Jayewardene". India Today.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "J.R. Jayewardene". BRITANNICA-Online. 28 October 2023.

- ^ a b c Stevens, William K.; Times, Special To the New York (20 October 1982). "ELECTION IN SRI LANKA CAPITALISM VERSUS SOCIALISM". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ a b "Obituary : J. R. Jayawardene". The Independent. 18 September 2011. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ a b Crossette, Barbara (2 November 1996). "J. R. Jayewardene of Sri Lanka Dies at 90; Modernized Nation He Led for 11 Years". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ a b Remembering the most dominant Lankan political figure

- ^ JR's 10th death anniversary today

- ^ Tribute: My father had many facets, not many faces. Daily News (Sri Lanka), Retrieved on 3 April 2018.

- ^ "India may train Sri Lankan troops". Archived from the original on 26 July 2010. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Humble son of a humble President

- ^ de Silva, K. M.; William Howard Wriggins (1988). J.R. Jayewardene of Sri Lanka. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press. p. 133. ISBN 0-8248-1183-6.

- ^ "JRJ's 102nd birth anniversary on Sept. 17"

- ^ De Silva, K. M.; Wriggins, William Howard (1988). J.R. Jayewardene of Sri Lanka: 1906-1956. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824811839. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ "J.R. Jayewardene | president of Sri Lanka". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ^ a b "JRJ: Farsighted statesman?". Archived from the original on 29 September 2019.

- ^ "Mr.J.R.Jayawardene on 'Sinhala Only and Tamil Also' in the Ceylon State Council".

- ^ "Sri Lanka's Role in Japanese Peace Treaty 1952: In Retrospect". 27 April 2015.

- ^ "State of Emergency" (PDF).

- ^ 1960-61 Ferguson's Ceylon Directory. Ferguson's Directory. 1961. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ "DIED JUNIUS RICHARD JAYEWARDENE". Asia Week. 15 November 1996. Archived from the original on 10 May 2009.

- ^ "Political forces - The constitution remains controversial". The Economist. 16 August 2006.

- ^ a b c "President Junius R. Jayawardena (1978-1988)". www.globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ Election heat and ‘Yahapalana’ antics

- ^ "Junius Jayewardene Dies". The Washington Post. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ Crossette, Barbara (2 November 1996). "J. R. Jayewardene of Sri Lanka Dies at 90; Modernized Nation He Led for 11 Years". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ a b c Stevens, William K. (22 April 1984). "RECENT FIGHTING IN SRI LANKA DIMS HOPES FOR ETHNIC PEACE". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ Fernando, Jude Lal (2014). "The Politics of Represenatations of Mass Atrocity in Sri Lanka and Human Rights Discourse: Challenge to Justice and Recovery". In Admirand, Peter (ed.). Loss and Hope: Global, Interreligious and Interdisciplinary Perspectives. London, U.K.: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-4725-2907-7.

- ^ Berlatsky, Noah, ed. (2014). Genocide & Persecution: Sri Lanka. Farmington Hills, U.S.: Greenhaven Press. p. 126. ISBN 9780737770162.

- ^ Short, Damien (2016). Redefining Genocide: Settler Colonialism, Social Death and Ecocide. London, U.K.: Zed Books. ISBN 9781783601707.

- ^ Sriskanda Rajah, A. R. (2017). Government and Politics in Sri Lanka: Biopolitics and Security. London, U.K.: Routledge. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-315-26571-1.

- ^ A visionary strategist

External links

edit- The JAYEWARDENE Ancestry

- The WIJEWARDENA Ancestry

- The Statesman Misunderstood

- Humble son of a humble President

- Website of the Parliament of Sri Lanka

- Official Website of United National Party (UNP)

- J.R. Jayewardene Centre

- 95th Birth Anniversary

- Remembering the most dominant Lankan political figure. by Padma Edirisinghe

- J.R. Jayewardene by Ananda Kannangara

- President JRJ and the Export Processing Zone By K. Godage

- Methek Kathawa Divaina Archived 15 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Methek Kathawa Divaina Archived 15 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine