John Anthony Burgess Wilson, FRSL (/ˈbɜːrdʒəs/;[2] 25 February 1917 – 22 November 1993) who published under the name Anthony Burgess, was an English writer and composer.

Anthony Burgess | |

|---|---|

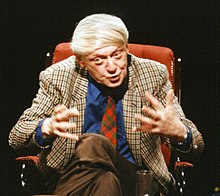

Burgess appearing on British television discussion programme After Dark "What is Sex For?" in 1988. | |

| Born | John Burgess Wilson 25 February 1917 Harpurhey, Manchester, England |

| Died | 22 November 1993 (aged 76) St John's Wood, London, England |

| Resting place | Monaco Cemetery |

| Pen name | Anthony Burgess, John Burgess Wilson, Joseph Kell[1] |

| Occupation |

|

| Alma mater | Victoria University of Manchester (BA English Literature) |

| Period | 1956–1993 |

| Notable works | The Malayan Trilogy (1956–59), A Clockwork Orange (1962) |

| Notable awards | Commandeur des Arts et des Lettres, distinction of France Monégasque, Commandeur de Merite Culturel (Monaco), Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, honorary degrees from St Andrews, Birmingham and Manchester universities |

| Spouse | |

| Children | Paolo Andrea (1964–2002) |

| Signature | |

| |

Although Burgess was primarily a comic writer, his dystopian satire A Clockwork Orange remains his best-known novel.[3] In 1971, it was adapted into a controversial film by Stanley Kubrick, which Burgess said was chiefly responsible for the popularity of the book. Burgess produced numerous other novels, including the Enderby quartet, and Earthly Powers. He wrote librettos and screenplays, including the 1977 television mini-series Jesus of Nazareth. He worked as a literary critic for several publications, including The Observer and The Guardian, and wrote studies of classic writers, notably James Joyce. A versatile linguist, Burgess lectured in phonetics, and translated Cyrano de Bergerac, Oedipus Rex, and the opera Carmen, among others. Burgess was nominated and shortlisted for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1973.[4][5]

Burgess also composed over 250 musical works; he considered himself as much a composer as an author, although he achieved considerably more success in writing.[6]

Biography

editEarly life

editIn 1917, Burgess was born at 91 Carisbrook Street in Harpurhey, a suburb of Manchester, England, to Catholic parents, Joseph and Elizabeth Wilson.[7] He described his background as lower middle class; growing up during the Great Depression, his parents, who were shopkeepers, were fairly well off, as the demand for their tobacco and alcohol wares remained constant. He was known in childhood as Jack, Little Jack, and Johnny Eagle.[8] At his confirmation, the name Anthony was added and he became John Anthony Burgess Wilson. He began using the pen name Anthony Burgess upon the publication of his 1956 novel Time for a Tiger.[7]

His mother Elizabeth (née Burgess) died at the age of 30 at home on 19 November 1918, during the 1918 flu pandemic. The causes listed on her death certificate were influenza, acute pneumonia, and cardiac failure. His sister Muriel had died four days earlier on 15 November from influenza, broncho-pneumonia, and cardiac failure, aged eight.[9] Burgess believed he was resented by his father, Joseph Wilson, for having survived, when his mother and sister did not.[10]

After the death of his mother, Burgess was raised by his maternal aunt, Ann Bromley, in Crumpsall with her two daughters. During this time, Burgess's father worked as a bookkeeper for a beef market by day, and in the evening played piano at a public house in Miles Platting.[8] After his father married the landlady of this pub, Margaret Dwyer, in 1922, Burgess was raised by his father and stepmother.[11] By 1924 the couple had established a tobacconist and off-licence business with four properties.[12] Burgess was briefly employed at the tobacconist shop as a child.[13] On 18 April 1938, Joseph Wilson died from cardiac failure, pleurisy, and influenza at the age of 55, leaving no inheritance despite his apparent business success.[14] Burgess's stepmother died of a heart attack in 1940.[15]

Burgess has said of his largely solitary childhood "I was either distractedly persecuted or ignored. I was one despised. ... Ragged boys in gangs would pounce on the well-dressed like myself."[16] Burgess attended St. Edmund's Elementary School, before moving on to Bishop Bilsborrow Memorial Elementary School, both Catholic schools, in Moss Side.[17] He later reflected "When I went to school I was able to read. At the Manchester elementary school I attended, most of the children could not read, so I was ... a little apart, rather different from the rest."[18] Good grades resulted in a place at Xaverian College (1928–37).[7]

Music

editBurgess was indifferent to music until he heard on his home-built radio "a quite incredible flute solo", which he characterised as "sinuous, exotic, erotic", and became spellbound.[19] Eight minutes later the announcer told him he had been listening to Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune by Claude Debussy. He referred to this as a "psychedelic moment ... a recognition of verbally inexpressible spiritual realities".[19] When Burgess announced to his family that he wanted to be a composer, they objected as "there was no money in it".[19] Music was not taught at his school, but at the age of about 14 he taught himself to play the piano.[20]

University

editBurgess had originally hoped to study music at university, but the music department at the Victoria University of Manchester turned down his application because of poor grades in physics.[21] Instead, he studied English language and literature there between 1937 and 1940, graduating with a Bachelor of Arts. His thesis concerned Marlowe's Doctor Faustus, and he graduated with an upper second-class honours, which he found disappointing.[22] When grading one of Burgess's term papers, the historian A. J. P. Taylor wrote: "Bright ideas insufficient to conceal lack of knowledge."[23]

Marriage

editBurgess met Llewela "Lynne" Isherwood Jones at the university where she was studying economics, politics and modern history, graduating in 1942 with an upper second-class.[24] Burgess and Jones were married on 22 January 1942.[7] She was the daughter of secondary school headmaster Edward Jones (1886–1963) and Florence (née Jones; 1867–1956), and reportedly claimed to be a distant relative of Christopher Isherwood, although the Lewis and Biswell biographies dispute this.[25] According to Burgess's own account, it was not from his wife that the alleged connection to Christopher Isherwood originated: "Her father was an English Jones, her mother a Welsh one. [...] Of Christopher Isherwood [...] neither the Jones father or daughter had heard. She was unliterary ..."[26] Biswell identifies Burgess as the origin of the alleged relationship with Christopher Isherwood—"if the rumour of an Isherwood affiliation signifies anything, it is that Burgess wanted people to believe that he was connected by marriage to another famous writer"—and notes that "Llewela was not, as Burgess claims in his autobiography, a 'cousin' of the writer Christopher Isherwood"; referring to a pedigree owned by the family, Biswell observes that "Llewela's father was descended from a female Isherwood" ... "which means going back four generations ... before encountering any Isherwoods", making any connection "at best" "tenuous and distant". He also establishes that per official records, "Llewela's family name was Jones, not (as Burgess liked to suggest) 'Isherwood Jones' or 'Isherwood-Jones'."[27]

Military service

editBurgess spent six weeks in 1940 as a British Army recruit in Eskbank before becoming a Nursing Orderly Class 3 in the Royal Army Medical Corps. During his service, he was unpopular and was involved in incidents such as knocking off a corporal's cap and polishing the floor of a corridor to make people slip.[28] In 1941, Burgess was pursued by the Royal Military Police for desertion after overstaying his leave from Morpeth military base with his future bride Lynne. The following year he asked to be transferred to the Army Educational Corps and, despite his loathing of authority, he was promoted to sergeant.[29] During the blackout, his pregnant wife Lynne was raped and assaulted by four American deserters; perhaps as a result, she lost the child.[7][30] Burgess, stationed at the time in Gibraltar, was denied leave to see her.[31]

At his stationing in Gibraltar, which he later wrote about in A Vision of Battlements, he worked as a training college lecturer in speech and drama, teaching alongside Ann McGlinn in German, French and Spanish.[citation needed] McGlinn's communist ideology would have a major influence on his later novel A Clockwork Orange. Burgess played a key role in "The British Way and Purpose" programme, designed to introduce members of the forces to the peacetime socialism of the post-war years in Britain.[32] He was an instructor for the Central Advisory Council for Forces Education of the Ministry of Education.[7] Burgess's flair for languages was noticed by army intelligence, and he took part in debriefings of Dutch expatriates and Free French who found refuge in Gibraltar during the war. In the neighbouring Spanish town of La Línea de la Concepción, he was arrested for insulting General Franco but released from custody shortly after the incident.[33]

Early teaching career

editBurgess left the army in 1946 with the rank of sergeant-major. For the next four years he was a lecturer in speech and drama at the Mid-West School of Education near Wolverhampton and at the Bamber Bridge Emergency Teacher Training College near Preston.[7] Burgess taught in the extramural department of Birmingham University (1946–50).[34]

In late 1950, he began working as a secondary school teacher at Banbury Grammar School (now Banbury School) teaching English literature. In addition to his teaching duties, he supervised sports and ran the school's drama society. He organised a number of amateur theatrical events in his spare time. These involved local people and students and included productions of T. S. Eliot's Sweeney Agonistes.[35] Reports from his former students and colleagues indicate that he cared deeply about teaching.[36]

With financial assistance provided by Lynne's father, the couple was able to put a down payment on a cottage in the village of Adderbury, close to Banbury. He named the cottage "Little Gidding" after one of Eliot's Four Quartets. Burgess cut his journalistic teeth in Adderbury, writing several articles for the local newspaper, the Banbury Guardian.[37][better source needed]

Malaya

editIn 1954, Burgess joined the British Colonial Service as a teacher and education officer in Malaya, initially stationed at Kuala Kangsar in Perak. Here he taught at the Malay College (now Malay College Kuala Kangsar – MCKK), modelled on English public school lines. In addition to his teaching duties, he was a housemaster in charge of students of the preparatory school, who were housed at a Victorian mansion known as "King's Pavilion".[38][39] A variety of the music he wrote there was influenced by the country, notably Sinfoni Melayu for orchestra and brass band, which included cries of Merdeka (independence) from the audience. No score, however, is extant.[40]

Burgess and his wife had occupied a noisy apartment where privacy was minimal, and this caused resentment. Following a dispute with the Malay College's principal about this, Burgess was reposted to the Malay Teachers' Training College at Kota Bharu, Kelantan.[41] Burgess attained fluency in Malay, spoken and written, achieving distinction in the examinations in the language set by the Colonial Office. He was rewarded with a salary increase for his proficiency in the language.

He devoted some of his free time in Malaya to creative writing "as a sort of gentlemanly hobby, because I knew there wasn't any money in it," and published his first novels: Time for a Tiger, The Enemy in the Blanket and Beds in the East.[42] These became known as The Malayan Trilogy and were later published in one volume as The Long Day Wanes.

Brunei

editAfter a brief period of leave in Britain during 1958, Burgess took up a further Eastern post, this time at the Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien College in Bandar Seri Begawan, Brunei. Brunei had been a British protectorate since 1888, and was not to achieve independence until 1984. In the sultanate, Burgess sketched the novel that, when it was published in 1961, was to be entitled Devil of a State and, although it dealt with Brunei, to avoid libel the action had to be transposed to an imaginary East African territory similar to Zanzibar, named Dunia. In his autobiography Little Wilson and Big God (1987), Burgess wrote:[43]

This novel was, is, about Brunei, which was renamed Naraka, Malay-Sanskrit for "hell". Little invention was needed to contrive a large cast of unbelievable characters and a number of interwoven plots. Though completed in 1958, the work was not published until 1961, for what it was worth it was made a choice of the book society. Heinemann, my publisher, was doubtful about publishing it: it might be libellous. I had to change the setting from Brunei to an East African one. Heinemann was right to be timorous. In early 1958, The Enemy in the Blanket appeared and at once provoked a libel suit.

About this time, Burgess collapsed in a Brunei classroom while teaching history and was diagnosed as having an inoperable brain tumour.[21] Burgess was given just a year to live, prompting him to write several novels to get money to provide for his widow.[21] He gave a different account, however, to Jeremy Isaacs in a Face to Face interview on the BBC The Late Show (21 March 1989). He said "Looking back now I see that I was driven out of the Colonial Service. I think possibly for political reasons that were disguised as clinical reasons".[44] He alluded to this in an interview with Don Swaim, explaining that his wife Lynne had said something "obscene" to the Duke of Edinburgh during an official visit, and the colonial authorities turned against him.[45][46] He had already earned their displeasure, he told Swaim, by writing articles in the newspaper in support of the revolutionary opposition party the Parti Rakyat Brunei, and for his friendship with its leader Dr. Azahari.[45][46] Burgess's biographers attribute the incident to the author's notorious mythomania. Geoffrey Grigson writes:[37]

He was, however, suffering from the effects of prolonged heavy drinking (and associated poor nutrition), of the often oppressive south-east Asian climate, of chronic constipation, and of overwork and professional disappointment. As he put it, the scions of the sultans and of the élite in Brunei "did not wish to be taught", because the free-flowing abundance of oil guaranteed their income and privileged status. He may also have wished for a pretext to abandon teaching and get going full-time as a writer, having made a late start.

Repatriate years

editBurgess was invalided home in 1959[47] and relieved of his position in Brunei. He spent some time in the neurological ward of a London hospital (see The Doctor is Sick) where he underwent cerebral tests that found no illness. On discharge, benefiting from a sum of money which Lynne Burgess had inherited from her father, together with their savings built up over six years in the East, he decided to become a full-time writer. The couple lived first in an apartment in Hove, near Brighton. They later moved to a semi-detached house called "Applegarth" in Etchingham, about four miles from Bateman's where Rudyard Kipling had lived in Burwash, and one mile from the Robertsbridge home of Malcolm Muggeridge.[48] Upon the death of Burgess's father-in-law, the couple used their inheritance to decamp to a terraced town house in Chiswick. This provided convenient access to the BBC Television Centre where he later became a frequent guest. During these years Burgess became a regular drinking partner of the novelist William S. Burroughs. Their meetings took place in London and Tangiers.[49]

A sea voyage the couple took with the Baltic Line from Tilbury to Leningrad in June 1961[50] resulted in the novel Honey for the Bears. He wrote in his autobiographical You've Had Your Time (1990), that in re-learning Russian at this time, he found inspiration for the Russian-based slang Nadsat that he created for A Clockwork Orange, going on to note, "I would resist to the limit any publisher's demand that a glossary be provided."[51][Notes 1]

Liana Macellari, an Italian translator twelve years younger than Burgess, came across his novels Inside Mr. Enderby and A Clockwork Orange, while writing about English fiction.[52] The two first met in 1963 over lunch in Chiswick and began an affair. In 1964, Liana gave birth to Burgess's son, Paolo Andrea. The affair was hidden from Burgess's alcoholic wife, whom he refused to leave for fear of offending his cousin (by Burgess's stepmother, Margaret Dwyer Wilson), George Dwyer, the Roman Catholic Bishop of Leeds.[52]

Lynne Burgess died from cirrhosis of the liver, on 20 March 1968.[7] Six months later, in September 1968, Burgess married Liana, acknowledging her four-year-old boy as his own, although the birth certificate listed Roy Halliday, Liana's former partner, as the father.[52] Paolo Andrea (also known as Andrew Burgess Wilson) died in London in 2002, aged 37.[53] Liana died in 2007.[52]

Tax exile

editBurgess was a Conservative (though, as he clarified in an interview with The Paris Review, his political views could be considered "a kind of anarchism" since his ideal of a "Catholic Jacobite imperial monarch" was not practicable) a (lapsed) Catholic and monarchist, harbouring a distaste for all republics.[54] He believed socialism for the most part was "ridiculous" but did "concede that socialised medicine is a priority in any civilised country today".[54] To avoid the 90% tax the family would have incurred because of their high income, they left Britain and toured Europe in a Bedford Dormobile motor-home. During their travels through France and across the Alps, Burgess wrote in the back of the van as Liana drove.

In this period, he wrote novels and produced film scripts for Lew Grade and Franco Zeffirelli.[52] His first place of residence after leaving England was Lija, Malta (1968–70). The negative reaction from a lecture that Burgess delivered to an audience of Catholic priests in Malta precipitated a move by the couple to Italy[52] after the Maltese government confiscated the property.[13] (He would go on to fictionalise these events in Earthly Powers a decade later.[13]) The Burgesses maintained a flat in Rome, a country house in Bracciano, and a property in Montalbuccio. On hearing rumours of a mafia plot to kidnap Paolo Andrea while the family was staying in Rome, Burgess decided to move to Monaco in 1975.[55] Burgess was also motivated to move to the tax haven of Monaco, as the country did not levy income tax, and widows were exempt from death duties, a form of taxation on their husband's estates.[56] The couple also had a villa in France, at Callian, Var, Provence.[57]

Burgess lived for a number of years in the United States, working as writer-in-residence at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1969, as a visiting professor at Princeton University with the creative writing program in 1970, and as a distinguished professor at the City College of New York in 1972. At City College he was a close colleague and friend of Joseph Heller. He went on to teach creative writing at Columbia University, lectured on the novel at the University of Iowa in 1975, and was and at the University at Buffalo in 1976. Eventually he settled in Monaco in 1976, where he was active in the local community, becoming a co-founder of the Princess Grace Irish Library, a centre for Irish cultural studies, in 1984.

In May 1988, Burgess made an extended appearance with, among others, Andrea Dworkin on the episode What Is Sex For? of the discussion programme After Dark. He spoke at one point about divorce:

Liking involves no discipline; love does ... A marriage, say that lasts twenty years or more, is a kind of civilisation, a kind of microcosm – it develops its own language, its own semiotics, its own slang, its own shorthand ... sex is part of it, part of the semiotics. To destroy, wantonly, such a relationship, is like destroying a whole civilisation.[58]

Although Burgess lived not far from Graham Greene, whose house was in Antibes, Greene became aggrieved shortly before his death by comments in newspaper articles by Burgess and broke off all contact.[37] Gore Vidal revealed in his 2006 memoir Point to Point Navigation that Greene disapproved of Burgess's appearance on various European television stations to discuss his (Burgess's) books.[37] Vidal recounts that Greene apparently regarded a willingness to appear on television as something that ought to be beneath a writer's dignity.[37] "He talks about his books," Vidal quotes an exasperated Greene as saying.[37] During this time, Burgess spent much time at his chalet 2 km (1.2 mi) outside Lugano, Switzerland.

Death

editAlthough Burgess wrote that he expected to "die somewhere in the Mediterranean lands, with an inaccurate obituary in the Nice-Matin, unmourned, soon forgotten",[59] he returned to die in Twickenham, an outer suburb of London, where he owned a house. Burgess died on 22 November 1993 from lung cancer, at the Hospital of St John & St Elizabeth in London. His ashes were inurned at the Monaco Cemetery.

The epitaph on Burgess's marble memorial stone, reads: "Abba Abba", which means "Father, father" in Aramaic, Arabic, Hebrew, and other Semitic languages and is pronounced by Christ during his agony in Gethsemane (Mark 14:36) as he prays God to spare him. It is also the title of Burgess's 22nd novel, concerning the death of John Keats. Eulogies at his memorial service at St Paul's, Covent Garden, London, in 1994 were delivered by the journalist Auberon Waugh and the novelist William Boyd.[citation needed] The Times obituary heralded the author as "a great moralist".[60] His estate was worth US$3 million and included a large European property portfolio of houses and apartments.[52]

Writing

editNovels

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2017) |

His Malayan trilogy The Long Day Wanes was Burgess's first published fiction. Its three books are Time for a Tiger, The Enemy in the Blanket and Beds in the East. Devil of a State is a follow-on to the trilogy, set in a fictionalised version of Brunei. It was Burgess's ambition to become "the true fictional expert on Malaya".[citation needed] In these works, Burgess was working in the tradition established by Kipling for British India, and Conrad and Maugham for Southeast Asia. Burgess operated more in the mode of Orwell, who had a good command of Urdu and Burmese (necessary for Orwell's work as a police officer) and Kipling, who spoke Hindi (having learnt it as a child). Like many of his fellow English expatriates in Asia, Burgess had excellent spoken and written command of his operative language(s), both as a novelist and as a speaker, including Malay.

Burgess's repatriate years (c. 1960–1969) produced Enderby and The Right to an Answer, which touches on the theme of death and dying, and One Hand Clapping, a satire on the vacuity of popular culture. The Worm and the Ring (1961) had to be withdrawn from circulation under the threat of libel action from one of Burgess's former colleagues, a school secretary.[61]

His dystopian novel, A Clockwork Orange, was published in 1962. It was inspired initially by an incident during the London Blitz of World War II in which his wife Lynne was robbed, assaulted, and violated by deserters from the US Army in London during the blackout. The event may have contributed to her subsequent miscarriage. The book was an examination of free will and morality. The young anti-hero, Alex, captured after a short career of violence and mayhem, undergoes a course of aversion therapy treatment to curb his violent tendencies. This results in making him defenceless against other people and unable to enjoy some of his favourite music that, besides violence, had been an intense pleasure for him. In the non-fiction book Flame into Being (1985), Burgess described A Clockwork Orange as "a jeu d'esprit knocked off for money in three weeks. It became known as the raw material for a film which seemed to glorify sex and violence". He added, "the film made it easy for readers of the book to misunderstand what it was about, and the misunderstanding will pursue me till I die". In a 1980 BBC interview, Burgess distanced himself from the novel and cinematic adaptations. Near the time of publication, the final chapter was cut from the American edition of the book.[citation needed]

Burgess had written A Clockwork Orange with 21 chapters, meaning to match the age of majority. "21 is the symbol of human maturity, or used to be, since at 21 you got to vote and assumed adult responsibility", Burgess wrote in a foreword for a 1986 edition. Needing money and thinking that the publisher was "being charitable in accepting the work at all," Burgess accepted the deal and allowed A Clockwork Orange to be published in the US with the twenty-first chapter omitted. Stanley Kubrick's film adaptation of A Clockwork Orange was based on the American edition, and thus helped to perpetuate the loss of the last chapter. In 2021, The International Anthony Burgess Foundation premiered a webpage cataloguing various stage productions of "A Clockwork Orange" from around the world.[62]

In Martin Seymour-Smith's Novels and Novelists: A Guide to the World of Fiction, Burgess related that he would often prepare a synopsis with a name-list before beginning a project. Seymour-Smith wrote:[63]

Burgess believes overplanning is fatal to creativity and regards his unconscious mind and the act of writing itself as indispensable guides. He does not produce a draft of a whole novel but prefers to get one page finished before he goes on to the next, which involves a good deal of revision and correction.

Nothing Like the Sun is a fictional recreation of Shakespeare's love-life and an examination of the supposedly partly syphilitic sources of the bard's imaginative vision. The novel, which drew on Edgar I. Fripp's 1938 biography Shakespeare, Man and Artist, won critical acclaim and placed Burgess among the first rank novelists of his generation. M/F (1971) was listed by the writer himself as one of the works of which he was most proud. Beard's Roman Women was revealing on a personal level, dealing with the death of his first wife, his bereavement, and the affair that led to his second marriage. In Napoleon Symphony, Burgess brought Bonaparte to life by shaping the novel's structure to Beethoven's Eroica symphony. The novel contains a portrait of an Arab and Muslim society under occupation by a Christian western power (Egypt by Catholic France). In the 1980s, religious themes began to feature heavily (The Kingdom of the Wicked, Man of Nazareth, Earthly Powers). Though Burgess lapsed from Catholicism early in his youth, the influence of the Catholic "training" and worldview remained strong in his work all his life. This is notable in the discussion of free will in A Clockwork Orange, and in the apocalyptic vision of devastating changes in the Catholic Church – due to what can be understood as Satanic influence – in Earthly Powers (1980).

Burgess kept working through his final illness and was writing on his deathbed. The late novel Any Old Iron is a generational saga of two families, one Russian-Welsh, the other Jewish, encompassing the sinking of the Titanic, World War I, the Russian Revolution, the Spanish Civil War, World War II, the early years of the State of Israel, and the rediscovery of Excalibur. A Dead Man in Deptford, about Christopher Marlowe, is a companion novel to Nothing Like the Sun. The verse novel Byrne was published posthumously.

Burgess announced in a 1972 interview that he was writing a novel about the Black Prince which incorporated John Dos Passos's narrative techniques, although he never finished writing it.[54] After Burgess's death, English writer Adam Roberts completed the novel, and it was published in 2018 under the title The Black Prince.[64] In 2019, a previously unpublished analysis of A Clockwork Orange was discovered titled, "The Clockwork Condition".[65] It is structured as Burgess's philosophical musings on the novel that won him so much acclaim.

Critical studies

editBurgess started his career as a critic. His English Literature, A Survey for Students was aimed at newcomers to the subject. He followed this with The Novel To-day (Longmans, 1963) and The Novel Now: A Student's Guide to Contemporary Fiction (New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1967). He wrote the Joyce studies Here Comes Everybody: An Introduction to James Joyce for the Ordinary Reader (also published as Re Joyce) and Joysprick: An Introduction to the Language of James Joyce. Also published was A Shorter "Finnegans Wake", Burgess's abridgement. His 1970 Encyclopædia Britannica entry on the novel (under "Novel, the"[66]) is regarded[by whom?] as a classic of the genre. Burgess wrote full-length critical studies of William Shakespeare, Ernest Hemingway and D. H. Lawrence, as well as Ninety-nine Novels: The Best in English since 1939.[67]

Screenwriting

editBurgess wrote the screenplays for Moses the Lawgiver (Gianfranco De Bosio 1974), Jesus of Nazareth (Franco Zeffirelli 1977), and A.D. (Stuart Cooper, 1985). Burgess was co-writer of the script for the TV series Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson (1980). The film treatments he produced include Amundsen, Attila, The Black Prince, Cyrus the Great, Dawn Chorus, The Dirty Tricks of Bertoldo, Eternal Life, Onassis, Puma, Samson and Delilah, Schreber, The Sexual Habits of the English Middle Class, Shah, That Man Freud and Uncle Ludwig. Burgess devised a Stone Age language for La Guerre du Feu (Quest for Fire; Jean-Jacques Annaud, 1981).

Burgess wrote many unpublished scripts, including Will! or The Bawdy Bard about Shakespeare, based on the novel Nothing Like The Sun. Encouraged by the success of Tremor of Intent (a parody of James Bond adventures), Burgess wrote a screenplay for The Spy Who Loved Me featuring characters from and a similar tone to the novel.[68] It had Bond fighting the criminal organisation CHAOS in Singapore to try to stop an assassination of Queen Elizabeth II using surgically implanted bombs at Sydney Opera House. It was described as "an outrageous medley of sadism, hypnosis, acupuncture, and international terrorism".[69] His screenplay was rejected, although the huge submarine silo seen in the finished film was reportedly Burgess's inspiration.[70]

Playwright

editAnthony Burgess's involvement with theatre started while attending university in Manchester, where directed plays and wrote theatre reviews. In Oxfordshire he was an active member of the Adderbury Drama Group, where he directed multiple plays, including Juno and the Paycock by Sean O'Casey, A Phoenix Too Frequent by Christopher Fry, The Giaconda Smile by Aldous Huxley and The Adding Machine by Elmer Rice.[71]

He wrote his first play in 1951, called The Eve of Saint Venus. There are no records of the play being performed, and in 1964 he turned the text into a novella. Throughout his life he wrote multiple adaptations and translations for theatre. His most famous work A Clockwork Orange, he adapted for the stage under the title A Clockwork Orange: A Play With Music. According to The International Anthony Burgess Foundation it had the following performances; an expanded edition of this play, with a facsimile of the handwritten score, appeared in 1999; A Clockwork Orange 2004, adapted from Burgess's novel by the director Ron Daniels and published by Arrow Books, was produced at the Barbican Theatre in London in 1990, with music by The Edge from U2.[71]

His other famous translations include the English version of Cyrano de Bergerac by Edmond Rostand. Recently two of his until now unpublished translations were published by Salamander Street, and imprint of Wordville, which the Foundation called a 'significant literary discovery'.[72] One is Miser! Miser! A translation of Molière's The Miser. Although the original French play is written in prose, Burgess remakes it in a mixture of verse and prose, in the style of his famous adaptation of Cyrano de Bergerac.[73] The other Chatsky subtitled 'The Importance of Being Stupid' based on Woe from Wit by Alexander Griboyedov. In Chatsky, Burgess remakes a classic Russian play in the spirit of Oscar Wilde.[73]

Music

editAn accomplished musician, Burgess composed regularly throughout his life, and once said: "I wish people would think of me as a musician who writes novels, instead of a novelist who writes music on the side."[74] He wrote more than 250 compositions in a variety of forms, including symphonies, concertos, chamber music, piano music, and works for the theatre.[6] His early introduction to music is lightly disguised as fiction in his novel The Pianoplayers (1986). Many of his unpublished compositions are listed in This Man and Music (1982).[6]

Orchestral and chamber

editHe began composing seriously while in the army during the war, and then while working as a teacher in Malaya, but could not earn a living from it. His early symphony, Sinfoni Melayu (now lost), was an attempt "to combine the musical elements of the country [Malaya] into a synthetic language which called on native drums and xylophones".[75] A second symphony has also been lost. But his Symphony No 3 in C was commissioned by the University of Iowa Symphony Orchestra in 1974, resulting in the first public performance of an orchestral work by Burgess – a momentous occasion for the composer which spurred him on to renew his composing activities with other large scale works, including a violin concerto for Yehudi Menuhin which remained unperformed due to the violinist's death.[76] More recently, the Symphony was broadcast on BBC Radio 3 as part of the Manchester International Festival in July 2017.[77]

Burgess also wrote a good deal of chamber music. He wrote for the recorder as his son played the instrument. Several works for recorder and piano, including the Sonata No. 1, Sonatina and Tre Pezzetti, have been recorded by John Turner with pianist Harvey Davies.[78] His collected guitar quartets have also been recorded by the Mēla Guitar Quartet.[79] A recently recovered work is a string quartet from 1980, influenced by Dmitri Shostakovich, which unexpectedly turned up in the archive of the International Anthony Burgess Foundation.[80] For piano, Burgess composed a set of 24 Preludes and Fugues, The Bad-Tempered Electronic Keyboard (1985), which has been recorded by Stephane Ginsburgh.[81]

Musicals and opera

editBurgess composed the operetta Blooms of Dublin in 1982, adapting the libretto from James Joyce's Ulysses. It is a very free interpretation of Joyce's text, with changes and interpolations by Burgess himself, all set to original music that blends opera with Gilbert and Sullivan and music hall styles. The musical was televised by the BBC, to mixed reviews.[82] He wrote the libretto for the 1973 Broadway musical Cyrano (music by Michael J. Lewis), using his own adaptation of the original Rostand play as his basis.[83] Burgess also produced a translation of Meilhac and Halévy's libretto to Bizet's Carmen, which was performed by the English National Opera in 1986, and wrote a new libretto for Weber's last opera Oberon (1826), reprinted alongside the original in Oberon Old and New. It was performed by the Glasgow-based Scottish Opera in 1985, but hasn't been revived since.[84]

Music and literature

editNearly all the writings, fiction and non-fiction, reflect his musical experiences. Biographical elements concerning musicians, particularly failed composers, occur everywhere. His early novel A Vision of Battlements (1965) concerns Richard Ennis, a composer of symphonies and concertos who is serving in the British army in Gibraltar. His last, Byrne (1995), a novel set in verse form, is about a minor modern composer who enjoys greater success in bed than he does in the concert hall. Fictional works mentioned in the novels often parallel Burgess's own real compositions, and provide a commentary on them, such as the cantata St Celia's Day, described in the 1976 novel Beard's Roman Women, which surfaced two years after the novel was published as a real Burgess work.

But the musical influences go far beyond the biographical. There are experiments combining musical forms and literature.[85] Tremor of Intent (1966), the James Bond spoof thriller, is set in sonata form. Mozart and the Wolf Gang (1991) mirrors the sound and rhythm of Mozartian composition, among other things attempting a fictional representation of Symphony No. 40.[86] Napoleon Symphony: A Novel in Four Movements (1974) is a literary interpretation of Beethoven's Eroica, while Beethoven's Symphony No. 9 features prominently in A Clockwork Orange (and in Stanley Kubrick's film version of the novel).

His use of language often highlights sound over meaning – in the made-up, Russian-influenced language "Nadsat" used by the narrator of A Clockwork Orange, in the wordless film script Quest for Fire (1981), where he invents a tribal language that prehistoric man might have spoken, and in the non-fiction work on the sound of language, A Mouthful of Air (1992).[87]

Musical enthusiasms

editOn the BBC's Desert Island Discs radio programme in 1966,[88] Burgess chose as his favourite music Purcell's "Rejoice in the Lord alway"; Bach's Goldberg Variations No. 13; Elgar's Symphony No. 1 in A-flat major; Wagner's "Walter's Trial Song" from Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg; Debussy's "Fêtes" from Nocturnes; Lambert's The Rio Grande; Walton's Symphony No. 1 in B-flat minor; and Vaughan Williams' On Wenlock Edge. A collection of essays on music by Burgess was published in 2024.[89]

Linguistics

edit"Burgess's linguistic training", wrote Raymond Chapman and Tom McArthur in The Oxford Companion to the English Language: "... is shown in dialogue enriched by distinctive pronunciations and the niceties of register".[90] During his years in Malaya, and after he had mastered Jawi, the Arabic script adapted for Malay, Burgess taught himself the Persian language, after which he produced a translation of Eliot's The Waste Land into Persian (unpublished). He worked on an anthology of the best of English literature translated into Malay, which failed to achieve publication. Burgess's published translations include two versions of Cyrano de Bergerac,[91] Oedipus the King[92] and Carmen.

Burgess's interest in language was reflected in the invented, Anglo-Russian teen slang of A Clockwork Orange (Nadsat), and in the movie Quest for Fire (1981), for which he invented a prehistoric language (Ulam) for the characters. His interest is reflected in his characters. In The Doctor is Sick, Dr Edwin Spindrift is a lecturer in linguistics who escapes from a hospital ward which is peopled, as the critic Saul Maloff put it in a review, with "brain cases who happily exemplify varieties of English speech". Burgess, who had lectured on phonetics at the University of Birmingham in the late 1940s, investigates the field of linguistics in Language Made Plain and A Mouthful of Air.

The depth of Burgess's multilingual proficiency came under discussion in Roger Lewis's 2002 biography. Lewis claimed that during production in Malaysia of the BBC documentary A Kind of Failure (1982), Burgess's supposedly fluent Malay was not understood by waitresses at a restaurant where they were filming. It was claimed that the documentary's director deliberately kept these moments intact in the film to expose Burgess's linguistic pretensions. A letter from David Wallace that appeared in the magazine of the London Independent on Sunday newspaper on 25 November 2002 shed light on the affair. Wallace's letter read, in part:

... the tale was inaccurate. It tells of Burgess, the great linguist, "bellowing Malay at a succession of Malayan waitresses" but "unable to make himself understood". The source of this tale was a 20-year-old BBC documentary ... [The suggestion was] that the director left the scene in, in order to poke fun at the great author. Not so, and I can be sure, as I was that director ... The story as seen on television made it clear that Burgess knew that these waitresses were not Malay. It was a Chinese restaurant and Burgess's point was that the ethnic Chinese had little time for the government-enforced national language, Bahasa Malaysia [Malay]. Burgess may well have had an accent, but he did speak the language; it was the girls in question who did not.

Lewis may not have been fully aware of the fact that a quarter of Malaysia's population is made up of Hokkien- and Cantonese-speaking Chinese. However, Malay had been installed as the National Language with the passing of the Language Act of 1967. By 1982 all national primary and secondary schools in Malaysia would have been teaching with Bahasa Melayu as a base language (see Harold Crouch, Government and Society in Malaysia, Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1996).

Archive

editThe largest archive of Anthony Burgess's belongings is housed at the International Anthony Burgess Foundation in Manchester, UK. The holdings include: handwritten journals and diaries; over 8000 books from Burgess's personal library; manuscripts of novels, journalism and musical compositions; professional and private photographs dating from between 1918 and 1993; an extensive archive of sound recordings; Burgess's music collection; furniture; musical instruments including two of Burgess's pianos; and correspondence that includes letters from Angela Carter, Graham Greene, Thomas Pynchon and other notable writers and publishers.[93] The International Anthony Burgess Foundation was established by Burgess's widow, Liana, in 2003.

Beginning in 1995, Burgess's widow sold a large archive of his papers at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin with several additions made in subsequent years.[94] Comprising over 136 boxes, the archive includes typed and handwritten manuscripts, sheet music, correspondence, clippings, contracts and legal documents, appointment books, magazines, photographs, and personal effects.

A substantial amount of unpublished and unproduced music compositions is included in the collection, along with a small number of audio recordings of Burgess's interviews and performances of his work.[95] Over 90 books from Burgess's library can also be found in the Ransom Center's holdings.[96] In 2014, the Ransom Center added the archive of Burgess's long-time agent Gabriele Pantucci, which also includes substantial manuscripts, sheet music, correspondence, and contracts.[97] Burgess's archive at the Ransom Center is supplemented by significant archives of artists Burgess admired including James Joyce, Graham Greene and D. H. Lawrence.

A small collection of papers, musical manuscripts and other items was deposited with the University of Angers in 1998. Its present whereabouts are unclear.[98][99]

Honours

edit- Burgess garnered the Commandeur des Arts et des Lettres distinction of France and became a Monégasque Commandeur de Merite Culturel (Monaco).

- He was a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature.

- In 1991 he was awarded the title of Companion of Literature by the Royal Society of Literature.[100]

- He took honorary degrees from St Andrews, Birmingham and Manchester universities.

- Earthly Powers was shortlisted for, but failed to win, the 1980 English Booker Prize for fiction (the prize went to William Golding for Rites of Passage).

Commemoration

edit- The International Anthony Burgess Foundation operates a performance space and café-bar at 3 Cambridge Street, Manchester.[101]

- The University of Manchester unveiled a plaque in October 2012 that reads: "The University of Manchester commemorates Anthony Burgess, 1917–1993, Writer and Composer, Graduate, BA English 1940". It was the first monument to Burgess in the United Kingdom.[102]

- The annual Observer/Anthony Burgess Prize for Arts Journalism is named in his honour.[103]

Selected works

editNovels

editNotes

edit- ^ A British edition of A Clockwork Orange (Penguin 1972; ISBN 0-14-003219-3) and at least one American edition did have a glossary. A note added: "For help with the Russian, I am indebted to the kindness of my colleague Nora Montesinos and a number of correspondents."

References

edit- ^ David 1973, p. 181

- ^ "anthony-burgess – Definition, pictures, pronunciation and usage notes". Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary. Archived from the original on 1 August 2019. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- ^ See the essay "A Prophetic and Violent Masterpiece" by Theodore Dalrymple in "Not With a Bang but a Whimper" (2008), pp. 135–149.

- ^ "Nomination Archive – Anthony Burgess". NobelPrize.org. March 2024. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ Kaj Schueler (2 January 2024). "Whites nobelpris – lugnet före stormen". Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ a b c "Composer". The International Anthony Burgess Foundation. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ratcliffe, Michael (2004). "Wilson, John Burgess [Anthony Burgess] (1917–1993)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/51526. Retrieved 20 June 2011. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b Lewis 2002, p. 67.

- ^ Lewis 2002, p. 62.

- ^ Lewis 2002, p. 64.

- ^ Lewis 2002, p. 68.

- ^ Lewis 2002, p. 70.

- ^ a b c Summerfield, Nicholas (December 2018). "Freedom and Anthony Burgess". The London Magazine. December/January 2019: 64–69.

- ^ Lewis 2002, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Lewis 2002, p. 107.

- ^ Lewis 2002, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Lewis 2002, p. 57.

- ^ Lewis 2002, p. 66

- ^ a b c Burgess 1982, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Burgess 1982, p. 19.

- ^ a b c "Anthony Burgess, 1917–1993, Biographical Sketch". Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas, Austin. 8 June 2004. Archived from the original on 30 August 2005.

- ^ Lewis 2002, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Lewis 2002, p. 95.

- ^ Lewis 2002, pp. 109–110.

- ^ Mitang, Herbert (26 November 1993). "Anthony Burgess, 76, Dies; Man of Letters and Music". The New York Times (obituary). Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ^ Little Wilson and Big God, Anthony Burgess, Vintage, 2002, p. 205.

- ^ The Real Life of Anthony Burgess, Andrew Biswell, Pan Macmillan, 2006, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Lewis 2002, p. 113.

- ^ Lewis 2002, p. 117.

- ^ Williams, Nigel (10 November 2002). "Not like clockwork". The Guardian. London, UK.

- ^ Lewis 2002, pp. 107, 128.

- ^ Colin Burrow (9 February 2006). "Not Quite Nasty". London Review of Books. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ Biswell 2006.

- ^ Anthony Burgess profile, britannica.com. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ^ Lewis 2002, p. 168.

- ^ Anthony Burgess; Earl G. Ingersoll; Mary C. Ingersoll (2008). Conversations with Anthony Burgess. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. xv. ISBN 978-1-60473-096-8.

- ^ a b c d e f Tiger: The Life and Opinions of Anthony Burgess, geoffreygrigson.wordpress.com; accessed 26 November 2014.

- ^ "SAKMONGKOL AK47: The Life and Times of Dato Mokhtar bin Dato Sir Mahmud". Sakmongkol.blogspot.com. 15 June 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ MCOBA – Pesentation(sic) by Old Boys at the 100 Years Prep School Centenary Celebration – 2013 Archived 26 November 2014 at archive.today, mcoba.org. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ^ Phillips, Paul (5 May 2004). "1954–59". The International Anthony Burgess Foundation. Archived from the original on 12 April 2010.

- ^ Lewis 2002, pp. 223–224.

- ^ Aggeler, Geoffrey (Editor) (1986) Critical Essays on Anthony Burgess. G K Hall. p. 1; ISBN 0-8161-8757-6.

- ^ Burgess, Anthony (2012), Little Wilson and Big God, Anthony Burgess, Random House, p. 431.

- ^ Conversations with Anthony Burgess (2008) Ingersoll & Ingersoll ed. p. 180.

- ^ a b Conversations with Anthony Burgess (2008), Ingersoll & Ingersoll, pp. 151–152.

- ^ a b "1985 interview with Anthony Burgess (audio)". Wiredforbooks.org. 19 September 1985. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Lewis 2002, p. 243.

- ^ Lewis 2002, p. 280.

- ^ Lewis 2002, p. 325.

- ^ Biswell 2006, p. 237.

- ^ Craik, Roger (January 2003). "'Bog or God' in A Clockwork Orange". ANQ: A Quarterly Journal of Short Articles, Notes and Reviews. 16 (4): 51–54. doi:10.1080/08957690309598481. S2CID 162676494.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Obituary: Liana Burgess". The Daily Telegraph. 5 December 2007. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- ^ Biswell 2006, p. 4.

- ^ a b c John Cullinan (2 December 1972). "Anthony Burgess, The Art of Fiction No. 48". The Paris Review (interview). No. 56. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ Asprey, Matthew (July–August 2009). "Peripatetic Burgess" (PDF). End of the World Newsletter (3): 4–7. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ^ Biswell 2006, p. 356.

- ^ Lewis 2002, p. 12.

- ^ Quoted in Anthony McCarthy (2016), Ethical Sex, Fidelity Press (ISBN 0-929891-17-1, 9780929891170)

- ^ Fitzgerald, Laurence (9 September 2015). "Anthony Burgess – Manchester's Neglected Hero?". I Love Manchester. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ^ "Anthony Burgess", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- ^ Lewis 2002, p. 9.

- ^ "A Clockwork Orange On Stage". 14 September 2023.

- ^ Rogers, Stephen D (2011). A Dictionary of Made-Up Languages. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4405-2817-0. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ Roberts, Adam; Anthony Burgess (2018). The Black Prince (New ed.). Unbound. ISBN 978-1-78352-647-5.

- ^ Picheta, Rob (25 April 2019). "Lost 'A Clockwork Orange' sequel discovered in author's archives". CNN Style.

- ^ Anthony Burgess, novel at the Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ The Neglected Books Page, neglectedbooks.com; accessed 26 November 2014.

- ^ Rubin, Steven Jay (1981). The James Bond films: a behind the scenes history. Westport, Conn.: Arlington House. ISBN 978-0-87000-523-7.

- ^ Field, Matthew (2015). Some kind of hero : 007 : the remarkable story of the James Bond films. Ajay Chowdhury. Stroud, Gloucestershire. ISBN 978-0-7509-6421-0. OCLC 930556527.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Barnes, Alan (2003). Kiss Kiss Bang! Bang! The Unofficial James Bond 007 Film Companion. Batsford. ISBN 978-0-7134-8645-2.

- ^ a b The International Anthony Burgess Foundation. "Playwright". The International Anthony Burgess Foundation. Retrieved 27 February 2024.

- ^ Alberge, Dalya (11 June 2022). "Anthony Burgess translation of Molière's The Miser comes to light for first time". The Guardian.

- ^ a b "Chatsky & Miser, Miser! Two Plays by Anthony Burgess". Salamander Street. Retrieved 27 February 2024.

- ^ Walter Clemons, "Anthony Burgess: Pushing On", The New York Times Book Review, 29 November 1970, p. 2.

- ^ Contemporary Composers, ed. Brian Morton and Pamela Collins, Chicago and London: St. James Press, 1992 – ISBN 1-55862-085-0

- ^ Concannon, Raymond (24 March 2022). "Concerto awaiting world premiere". violinist.com.

- ^ "Manchester International Festival: Symphony in C", International Burgess Foundation.

- ^ "The Man And His Music". The International Anthony Burgess Foundation. 30 September 2013. Archived from the original on 30 March 2023.

- ^ Anthony Burgess: Complete Guitar Quartets, Naxos 8.574423 (2023).

- ^ Alberge, Dalya (19 November 2023). "Newly discovered string quartet by Clockwork Orange author Anthony Burgess to have premiere". The Observer. Archived from the original on 19 November 2023.

- ^ Grand Piano CD GP 773 (2018).

- ^ The Listener, 7 January, 1982, p. 18.

- ^ Ken Mandelbaum. Not Since Carrie: Forty Years of Broadway Musical Flops (1991), pages 191–92.

- ^ Roger Lewis. Anthony Burgess. Thomas Dunne Books, 2004. ISBN 0-312-32251-8

- ^ Shockley, Alan (2017). Music in the Words: Musical Form and Counterpoint in the Twentieth-Century Novel. Routledge. OCLC 1001968147. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ Burgess, Anthony (Winter 1992). "Mozart and the Wolf Gang". The Wilson Quarterly. 16 (1): 113. JSTOR 40258243. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ "BOOK REVIEW / Whistles while you work and other wizard prangs: 'A Mouthful of Air' – Anthony Burgess: Hutchinson, 16.99". The Independent. 31 October 1992.

- ^ "Anthony Burgess". Desert Island Discs. BBC. 28 November 1966. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- ^ The Devil Prefers Mozart: On Music and Musicians, 1962–1993, ed. Paul Phillips. Carcanet Press, 2024.

- ^ McArthur, Tom, ed. (1992). The Oxford companion to the English language. Oxford University Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-19-214183-5. LCCN 92224249. OCLC 1150933959.

- ^ Rostand, Edmond; Anthony Burgess (1991). Cyrano de Bergerac, translated and adapted by Anthony Burgess (New ed.). Nick Hern Books. ISBN 978-1-85459-117-3.

- ^ Sophocles (1972). Oedipus the King. Translated by Anthony Burgess. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-0667-2.

- ^ "About the collections". Archived from the original on 22 June 2019. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- ^ "Anthony Burgess". Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- ^ "Anthony Burgess: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center". norman.hrc.utexas.edu. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ "University of Texas Libraries / HRC". catalog.lib.utexas.edu. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ^ "Gabriele Pantucci Collection of Anthony Burgess A Preliminary Inventory of His Collection at the Harry Ransom Center". norman.hrc.utexas.edu. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ Archive list of items

- ^ The Anthony Burgess Center (archived)

- ^ "Companions of Literature". Royal Society of Literature. 2 September 2023.

- ^ "International Anthony Burgess Foundation Manchester". www.theskinny.co.uk.

- ^ "Your Manchester Online". November 2012. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ "The Observer/Anthony Burgess Prize for Arts Journalism | The Guardian". www.theguardian.com. Retrieved 26 July 2024.

Bibliography

edit- Biswell, Andrew (2006), The Real Life of Anthony Burgess, Picador, ISBN 978-0-330-48171-7

- Burgess, Anthony (1982), This Man And Music, McGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-008964-8

- David, Beverley (July 1973), "Anthony Burgess: A Checklist (1956–1971)", Twentieth Century Literature, 19 (3): 181–88, JSTOR 440916

- Lewis, Roger (2002), Anthony Burgess, Faber and Faber, ISBN 978-0-571-20492-2

Further reading

editSelected studies

edit- Geoffrey Aggeler, Anthony Burgess: The Artist as Novelist (Alabama, 1979, ISBN 978-0-8173-7106-7).

- Boytinck, Paul. Anthony Burgess: An Annotated Bibliography and Reference Guide. New York, London: Garland Publishing, 1985. xxvi, 349 pp. Includes introduction, chronology and index, ISBN 978-0-8240-9135-4.

- Anthony Burgess, "The Clockwork Condition". The New Yorker. June 4 & 11, 2012. pp. 69–76.

- Samuel Coale, Anthony Burgess (New York, 1981, ISBN 978-0-8044-2124-9).

- A. A. Devitis, Anthony Burgess (New York, 1972).

- Carol M. Dix, Anthony Burgess (British Council, 1971. Northcote House Publishers, ISBN 978-0-582-01218-9).

- Martine Ghosh-Schellhorn, Anthony Burgess: A Study in Character (Peter Lang AG, 1986, ISBN 978-3-8204-5163-4).

- Richard Mathews, The Clockwork Universe of Anthony Burgess (Borgo Press, 1990, ISBN 978-0-89370-227-4).

- Paul Phillips, The Music of Anthony Burgess (1999).

- Paul Phillips, "Anthony Burgess", New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd ed. (2001).

- Paul Phillips, A Clockwork Counterpoint: The Music and Literature of Anthony Burgess (Manchester University Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0-7190-7204-8).

- John J. Stinson, Anthony Burgess Revisited (Boston, 1991, ISBN 978-0-8057-7000-1).

Collections

edit- Burgess, Anthony (2020). Jonathan Mann (ed.). Collected Poems. Carcanet Press. ISBN 978-1-80017-013-1.

- The largest collection of Burgess's papers and belongings, including literary and musical papers, is archived at the International Anthony Burgess Foundation (IABF) in Manchester.

- Another large archival collection of Burgessiana is held at the Harry Ransom Center of the University of Texas at Austin: Aggeler, Geoff; Birkett, Michael; Bottrall, Ronald; Burroughs, William S.; Caroline, Princess of Monaco; Greene, Graham; Joannon, Pierre; Jong, Erica; Kollek, Teddy. "Anthony Burgess: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center". norman.hrc.utexas.edu. Retrieved 14 May 2019.; "Gabriele Pantucci Collection of Anthony Burgess A Preliminary Inventory of His Collection at the Harry Ransom Center". norman.hrc.utexas.edu. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- The Anthony Burgess Center of the University of Angers, with which Burgess's widow Liana was connected, also has some papers.

- "Anthony Burgess fonds". McMaster University Library. The William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

External links

edit- The International Anthony Burgess Foundation

- The Anthony Burgess Papers at the Harry Ransom Center

- The Gabriele Pantucci Collection of Anthony Burgess at the Harry Ransom Center

- The Anthony Burgess Center at the University of Angers

- BBC TV interview

- Burgess reads from A Clockwork Orange

- Anthony Burgess at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database