The Titanic International Society is an American 501(c)(3) non-profit organization dedicated to preserving the history of the Titanic and the events surrounding its sinking on April 15, 1912, when more than 1,500 people died.[1][2] The society holds biennial conventions and occasional special events, such as memorial ceremonies at sites associated with the Titanic and a tribute to Titanic writer Walter Lord in his Baltimore hometown. It is one of several organizations worldwide dedicated to the memory of the Titanic.[3]

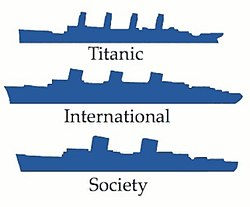

The logo profiles the Titanic, SS Normandie, and SS United States | |

| Founded | 1989 |

|---|---|

| Focus | Preservation of the history of the Titanic and other ocean liners |

| Location | |

President | Charles A. Haas |

Treasurer | Robert Bracken |

| Website | titanicinternationalsociety |

Formerly called | Titanic International |

The society publishes Voyage, an illustrated quarterly journal. In addition to stories about the Titanic and her passengers and crew, other ships related to the Titanic disaster are also covered, such as the SS Californian and the rescue ship RMS Carpathia. Although Titanic is the Society's primary focus, issues of Voyage have also featured other famous ocean liners. The Society's logo reflects these multiple interests, with silhouettes depicting the Titanic, the acclaimed French vessel SS Normandie, and SS United States, the world's fastest liner.

History

editFounding

editThe Titanic International Society began in 1989 to perpetuate the memory of Titanic. Initially called Titanic International, the newly-formed organization had 50 members in its first year.[4] Among its founding members were Robert M. DiSogra, Michael Findlay, and Charles A. Haas, all of whom later served as Society presidents. The group desired to promote greater knowledge of the circumstances surrounding the ill-fated White Star Liner's disastrous maiden voyage and the people who sailed aboard her.[1][5] Haas and another founding member, John P. Eaton, had co-authored Titanic: Triumph and Tragedy in 1986.[6][7] Titanic International's inaugural meeting took place on Saturday, April 15, 1989, at the Philadelphia Maritime Museum (now the Independence Seaport Museum), with Titanic survivor Louise Kink Pope as guest of honor.[8]

1990s

editIn 1991, Louise Pope again attended the Society's convention in Rochelle Park, New Jersey,[9] which included her visit to the old Pier 54 in Manhattan, where Carpathia had docked with the Titanic survivors. She also participated in that convention's "Dream of Freedom" ceremony at Ellis Island, where the Society presented the Ellis Island National Museum of Immigration with a plaque in memory of the immigrants traveling to America in Third Class on the Titanic, who died at sea when Titanic foundered.[10][11] The plaque remembered those, "...who never made it to safety and were lost at sea".[10]

Other Titanic survivors attending Society conventions were Edith Haisman, Eleanor Ileen Johnson, Millvina Dean, Michel Navratil, Marjorie Newell Robb, and Frank Philip Aks. Morro Castle survivors Agnes Prince Margolis, Ruth Prince Coleman, and Dolly McTigue, and Andrea Doria survivor Jerome Reinert were honored guests at the 1991 and 1992 conventions, respectively.[9][12]

Memorials to victims

editIn 1990–1991, the Society worked to identify six Titanic disaster victims buried in unmarked graves at Fairview Lawn Cemetery in Halifax, Nova Scotia, so that their headstones could be inscribed with their names.[13] In September 1991, more than 50 society members joined a cruise to Halifax aboard the Cunard Line's Queen Elizabeth 2. While there, Society members attended the unveiling of the newly inscribed gravestones, made possible by the society's research.[14] Titanic survivor Louise Pope joined Halifax Mayor Ronald Wallace at the Fairview Lawn Cemetery unveiling ceremonies (pictured).[13] The event was attended by hundreds of Halifax residents and televised by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. The QE2's Captain, Robin Woodall, also participated, expressing to the assemblage the Cunard Line's pride in Carpathia's vital role in rescuing the survivors.[13]

In cemeteries in the northeastern U.S., the Society has also provided headstones for the previously unmarked graves of Titanic second-class passenger Marshall Drew; U.S. Sea Post officer John Starr March; third-class passengers Oscar Palmquist and Catherine Buckley; and Robert J. Hopkins, an able seaman aboard Titanic.[15][16][17]

In 1993, the society presented a plaque to the Smithsonian Institution's National Postal Museum in Washington, D.C., in memory of the American and British postal service workers who died when Titanic sank. At a New Jersey cemetery where an American Titanic postal worker is buried, a headstone was added by the Society to commemorate his death in the line of duty aboard Titanic, which an existing grave marker omitted.[18][19] A "Salute to Walter Lord" was held in nearby Baltimore, Maryland, the hometown of the celebrated author. He was feted for his seminal work, A Night to Remember, the narrative of the Titanic disaster which inspired television and film adaptations and led to renewed interest in the ship's fate.[20] Also that year, Society founding members Haas and Eaton made dives to the Titanic's wrecksite.[5][7] The then 67-year old Eaton was said to be the oldest person at the time to do so.[2] Haas said later that seeing the sunken ocean liner's great size and the devastation at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean was "emotionally overwhelming".[21] Haas, then a New Jersey high school English and journalism teacher,[22] and Eaton wrote first-person accounts of their expedition experiences for Voyage.[23]

The Cunard Line's former Pier 54 site in Manhattan was revisited in 1997 for an 85th anniversary memorial service. By then, membership had grown to 900 individuals in 24 countries.[4] Producers of the Tony Award-winning musical, Titanic, consulted the Society's archives for accurate portrayal of the play's characters before the show's Broadway debut in 1997.[24] In early 1998, the trustees voted to amend the organization's name to "Titanic International Society". On July 28, 1999, the Society returned to Halifax's Fairview Lawn Cemetery and presented a ceremony "For the Children," remembering the 53 children under age 14 who perished in the disaster.[25]

Support for recovery efforts

editThe Society was an early supporter of the efforts by RMS Titanic Inc. to recover, conserve, and exhibit Titanic artifacts, by providing historical information to the company and publishing multiple articles in Voyage about its activities.[5] The Society believes it is important to retrieve artifacts from the disaster before they disintegrate completely and are gone forever, for future generations to see firsthand.[21] Some members served in an advisory capacity as consultants.[24][26][27] In 1990, the Society's first full year of operation, it published a featured article, "Recovery and Exploration: The 1987 Titanic expedition offers new insights into its operations, plans", describing the anticipated recovery and exhibition plans.[28] The Society defends the recovery of such artifacts as spoons, luggage, wine bottles, and a portion of Titanic's hull from the wreckage, despite criticism.[29][30] The Society's journal, Voyage featured the recovery with photos in the Winter 2003 issue.[31]

When George Tulloch, one of the founders of RMS Titanic Inc. died early in 2004, then-Titanic International Society president Michael Findlay lauded his work, saying, "He has done more to preserve the memory of Titanic than anyone else". Shortly before his death, Tulloch had written in Voyage of his hope that future generations would "... understand the reverence and dedication for this tragic story" motivating the salvagers.[32] By 2013, more than 25 million people had visited the Titanic exhibits in Orlando, Atlanta, Los Angeles, Las Vegas, and elsewhere, said Premier Exhibitions (the affiliate of RMS Titanic Inc.).[33]

The Society has occasionally been contacted to authenticate various Titanic-related items.[34] A dollar bill signed by the Titanic's barber, for example, was verified by Society co-founder Michael Findlay and displayed on television by his colleague Charles Haas.[35]

2000–present

editAt its 2003 convention in Newport, Rhode Island, the Society’s guest of honor was Lusitania survivor Barbara McDermott.[36] In 2004, the Society's journal, Voyage, featured a cover story on the life of William MacQuitty, who died in February of that year at age 98.[37] MacQuitty was the British producer of the 1958 film, A Night to Remember, which recreated the story of the sinking of the Titanic. As a six-year old, he had witnessed her launch in Belfast. The Voyage cover was headlined, "A gentleman to remember".[37]

At the 2008 convention, members toured sites connected to the White Star Line in New York City, the intended destination of Titanic.[7] In 2011, the Society journeyed to Ireland, where sites connected to the Titanic saga were on the itinerary, in a joint gathering with the Belfast Titanic Society marking the 100th anniversary of the Titanic's launch there in 1911. Included was a visit to the Thomas Andrews Memorial Hall, built in Comber to honor the memory of the Titanic's designer, a tour of the Harland and Wolff shipyard, a visit to the Ulster Folk and Transport Museum to view its Titanic exhibit, and a banquet at Belfast City Hall, attended by 300 guests.[38]

In April, 2012, members of the Society presented lectures to participants aboard two cruise ships sailing to the place in the Atlantic Ocean where Titanic sank a century before, 400 miles (640 km) off the coast of Newfoundland. Aboard the MV Balmoral, Society members were among the 1,309 passengers who sailed from Southampton on April 8, re-tracing Titanic's fateful route across the Atlantic. The Society's Winter 2012 Voyage magazine cover story, "The 2012 Titanic Memorial Cruises", gave extensive illustrated coverage to the centennial commemoration. Charles Haas described the poignant onboard memorial service held on April 15 over the place where Titanic sank. Addressing the Balmoral assemblage, retired Cunard Commodore Ron Warwick said:

"We come together in a spirit of remembrance to give thanks for the lives of the 1,503 men, women, and children lost to the freezing Atlantic 100 years ago tonight, when the Titanic met its end under these stars and on this very spot ... Darkness was on the face of the deep. We remember the families torn apart by this tragedy ..."[39]

At exactly 2:20 am, the moment when the great ship foundered, the Balmoral's whistle gave a sustained blast. As a White Star Line burgee flew from the ship's fantail, three wreaths of remembrance were lowered to the ocean's surface and the crowd sang Eternal Father, Strong to Save, with much emotion, Haas wrote.[39]

A highlight in 2013 was the recovery of a long-lost memorial plaque dedicated to the eight members of Titanic's orchestra, all of whom played to the very end as she sank and went down with the ship. Inscribed on the bronze plaque, commissioned in 1912 by the Musical Mutual Protective Union in New York City, is the legend: "A tribute to the bandsmen of the Titanic. When the order was ‘each man for himself,’ these heroes remained on board and played till the last". It lists bandleader Wallace Hartley and the names of the other seven musicians, surmounted by a figure in relief holding a laurel wreath over the ocean's waves, in tribute to their selfless heroism.[40] Found in a scrap yard, the recovered plaque was rededicated and put on public display at the Titanic The Experience exhibit in Orlando, Florida, on August 15, at a reception co-hosted by the Society and RMS Titanic. The plaque was subsequently acquired in 2016 by the American Federation of Musicians Local 802 in New York City, where it is now displayed in their headquarters lobby.[41]

Current leadership and activities

editThe Society is led by an eleven-member board of trustees, elected by the membership to three-year terms. From among their number, the trustees elect the Society's three officers – president, treasurer and corporate secretary – and appoint the Society's historian.[42] Officers’ responsibilities are enumerated in the Society's bylaws. Members occasionally make multimedia presentations about the Titanic to the public.[1] As of 2020[update], Charles Haas is president, and Robert Bracken is treasurer. Like many members, Bracken first became interested in the Titanic after reading Walter Lord's book, A Night to Remember. At the time, he was just in junior high school, reported NJTV.[43] Past-president and founding member Michael Findlay likewise became fascinated by the Titanic saga after doing a book report for school on A Night to Remember, as a 9-year old.[24] Haas told the Saturday Evening Post magazine in 2020 that the Society regularly surveys its members to encourage group affinity.[30]

Co-founder John P. ("Jack") Eaton (1926–2021) was the Society's historian until his death on January 29, 2021. He was an authority on Titanic research, as detailed in the multiple printings of his co-authored book, Titanic: Triumph and Tragedy. Eaton made frequent appearances on television documentaries sharing his wealth of knowledge about the disaster and was an advisor for Titanic-related exhibitions and the National Geographic.[44][45]

One of the society's principal endeavors is publication of a quarterly journal, Voyage, containing illustrated articles pertaining to the Titanic, her sister ship RMS Olympic, and other famous vessels, and those who sailed them.[46] The controversial role of SS Californian and the rescue ship RMS Carpathia have been covered in depth. Although the Titanic is the Society's primary focus, Voyage has also covered other notable ocean liner disasters, such as those involving the Morro Castle, RMS Lusitania, and the SS City of Benares, which was torpedoed by a German submarine in World War II and sunk while evacuating children from Great Britain to Canada.[47][48][49] Past issues have featured other iconic ships as well, such as the Cunard liners Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth 2.[50]

Conventions are now held every two years, with guest speakers and authors sharing their expert knowledge on maritime subjects (in earlier years, the Society's gatherings were an annual event).[5] In 2007, several worldwide Titanic-interest groups came together in Halifax, Nova Scotia, for the 95th anniversary of the ship's sinking. The British Titanic Society took the lead in planning the event, which the Titanic International Society co-sponsored. Representatives from the Scandinavian Titanic Society, Swiss Titanic Society, German Titanic Society ("Der Deutsche Titanic-Verein"), and the Irish Titanic Historical Society attended.[51] The Society had joint conventions with the Belfast Titanic Society in 2011 and the Titanic Society of Atlantic Canada in 2018.[52][53] Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Society's 2020 convention, planned for Boston, Massachusetts, was rescheduled tentatively for June 2022.[54]

The Society participates in the Coast Guard's annual observance of the disaster, placing a commemorative wreath over the vessel's watery grave in the Atlantic Ocean.[55] On April 15, 2010, the traditional wreath laying in the Atlantic Ocean was preceded by a special memorial service at Fairview Lawn Cemetery in Halifax.[56]

In the media

editThe society and its individual members are frequently consulted by the news media regarding aspects of the Titanic disaster, especially when the ill-fated liner is in the news, with various trustees responding to queries.[57] On the eve of the December, 1997, release of the film Titanic, Charles Haas was asked about predictions that it would flop, accurately predicting that the film would be a box office hit.[4]

On the 75th anniversary of Titanic's sinking in 1987, Haas explained the public's ongoing fascination with the disaster: "We admire the great display of courage and heroism — latent qualities in people not often seen in this hurry-up world".[58] In a 2020 interview with the Saturday Evening Post magazine, Haas said that the almost three hours it took for the Titanic to sink allowed time for the tragic drama to unfold, "where we see human behavior at its best and its worst".[30] Both Haas and John Eaton appeared in the acclaimed television documentary, Titanic: The Complete Story, produced by A&E Television Networks in 1994 and Haas narrated the Discovery Channel program Titanic: Untold Stories, which featured footage taken during his second dive to the wreck in 1996.[1][4][7]

In 2007, the identity of "The Unknown Child" buried in Fairview Lawn Cemetery was finally established by DNA evidence to be Sidney Leslie Goodwin, after having been thought by researchers to be another toddler. The Society had been following the ongoing research closely, having previously published an article, "The Identity of Titanic's Unknown Child", in its Fall 2002 Voyage journal.[59] Haas was asked by USA Today for comment on the new finding. He said, "Science is a fluid thing, it's not set in concrete".[60]

When the last living Titanic survivor, Millvina Dean, died in 2009, Haas called her a "remarkable, sparkling lady". Speaking for the Society, he told the Chicago Tribune, "She knew her place in history and was always willing to share her story with others".[61] The BBC also interviewed him about the death of Dean, whom he had met several times. He told the British audience: "She had a marvelous approach to life. It is almost as if God gave her the gift and she really took advantage of it".[62]

Another book by Eaton and Haas, Titanic: Destination Disaster: The legends and the reality,[63] was subsequently cited by Stephen Brown, et al., in the academic publication, Journal of Consumer Research. In their journal article, "Titanic: Consuming the Myths and Meanings of an Ambiguous Brand", the authors examined the public's fascination with all aspects of the Titanic story and its marketing, while separating fact from fiction. They referred to the book's factual recounting of the ship's construction and launching at the Harland and Wolff shipyards.[33]

In November 2020, two Society trustees appeared on the History Channel's program Titanic: Lost Evidence, one of the History's Mysteries episodes on U.S. television. Also that month, some Society members appeared on the PBS television program, Abandoning the Titanic, part of the Secrets of the Dead series.[64] The show discussed a disputed theory that the Canadian Pacific steamship Mount Temple, and not the Californian, was the “mystery ship” observed in the distance from the decks of the sinking Titanic and that the Californian's captain, Stanley Lord, was wrongly made the scapegoat for failing to reach Titanic before she went down.[64] Although the show was co-produced by Senan Molony, who is a Society member, the controversial claim is not one the Society has endorsed. In other endeavors by individual Society members, three are leading a team designing Titanic: Honor and Glory, a virtual reality game with highly realistic graphics set aboard Titanic.

The Society was approached by the news media when Australian tycoon Clive Palmer announced plans to build and sail a replica, dubbed Titanic II. Haas doubted the likelihood of commercial success such a reincarnation of the original Titanic would have, telling the New York Times, "As good as the Titanic was in her day, it would be a practical and financial disaster", due to the relative lack of onboard activities and amenities today's traveling public expects, such as theaters, casinos, and waterslides.[57] Commenting on the project's appropriateness, Scientific American quoted him as saying, "It's a matter of sensitivity, respect and thoughtfulness ... We commemorate tragedies and those lost in them, not duplicate them".[65]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d Krengel, Sharon (February 17, 2000). "Organization keeps memory of Titanic alive". Asbury Park Press. p. 9. Retrieved October 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Titanic International Society — Researching the liners of the world". Titanic International Society. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ^ Carey, Lynn (January 4, 1998). "Some Titanic tidbits to satisfy new enthusiasts". Charlotte Observer. p. 4F. Retrieved October 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d Makin, Robert (December 18, 1997). "'Titanic' timing may not be right". Courier-News. p. 1. Retrieved October 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d Yoo, Aileen S. (January 7, 1996). "A Titanic Interest". Asbury Park Press. p. A4. Retrieved October 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Titanic: Triumph and Tragedy. WorldCat. OCLC 1166502179.

- ^ a b c d Ash, Lorraine (January 6, 2008). "Teacher's Deep Subject". Daily Record. p. 1. continued: "Titanic". Daily Record. 6 January 2008. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Philadelphia 'launches' TI". Voyage (1). Titanic International: 28. July 1989.

- ^ a b Imhoff, Ernest F. (July 8, 1991). "Shipwreck buffs court disaster". Evening Sun. p. D1. Retrieved October 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Figdore, Sherry (April 18, 1992). "Titanic survivor on hand for show about the disaster". Asbury Park Press. p. C9. Retrieved October 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Dream of Freedom". Voyage (9). Titanic International: 6. Autumn 1991.

- ^ "A special weekend in New York". Voyage (12). Titanic International: 178. Summer 1992.

- ^ a b c "Fairview Lawn Cemetery ceremonies". Voyage (10). Titanic International: 54–57. Winter 1992.

- ^ Hustak, Alan (September 22, 1991). "Six victims of Titanic identified – 80 years later". Montreal Gazette. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Marsh, Shawn (May 15, 2016). "Heroic Titanic seaman to get grave stone decades after death". Associated Press. Retrieved October 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Finally resting in peace". Kearny, NJ: The Observer online. May 17, 2016. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- ^ "The Untold Story of Robert Hopkins". Voyage (97). Titanic International: 20. Autumn 2016.

- ^ "Tribute planned for New Jersey Titanic victim". Herald News. April 12, 1993. Retrieved March 7, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "In memory of the Titanic postal workers". Voyage (16). Titanic International: 158. Autumn 1993.

- ^ "About Us". Titanic International Society. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- ^ a b Colimore, Edward (December 9, 1994). "Before time runs out, Titanic devotees urge rescue of relics". Philadelphia Inquirer. p. B11. Retrieved October 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Harley, Bobbi (August 30, 1989). "Randolph teacher wins county recognition". Daily Record. Morristown, NJ. p. 3. Retrieved October 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Haas, Charles A.; Eaton, John P. (Winter 1993). "Diving the Titanic". Voyage. Titanic International.

- ^ a b c Longo, Rosalie (March 20, 1997). "Titanic Buffs Hope Musical Will Float". Herald-News. p. B7. Retrieved October 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "For the Children". Voyage (31). Titanic International Society: 124. Winter 2000.

- ^ Berry, Coleen Dee (December 20, 1995). "For sale: Coal from the Titanic". Central New Jersey Home News & Tribune. p. A4. Retrieved October 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Coal". Asbury Park Press. December 17, 1995. p. A10. Retrieved October 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Recovery and Exploration: The 1987 Titanic expedition offers new insights into its operations, plans". Voyage (5). Titanic International: 14. July 1990.

- ^ Colimore, Edward (December 11, 1994). "Titanic International works to recover objects from sunken liner". Ottawa Citizen. p. C10. Retrieved October 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Cameron, Emlyn (November–December 2020). "Titanic Fanatics". Saturday Evening Post. 292 (6): 51.

- ^ "The five-year anniversary of recovering the 'Big Piece'". Voyage (46). Titanic International Society. Winter 2003.

- ^ "G. Tulloch, Titanic Salvager, Dies". Hartford Courant. February 3, 2004. p. B6. Retrieved October 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Brown, Stephen; McDonagh, Pierre; Schultz II, Clifford J. (December 2013). "Titanic: Consuming the Myths and Meanings of an Ambiguous Brand". Journal of Consumer Research. 40 (4). Oxford University Press: 595–614. doi:10.1086/671474. JSTOR 10.1086/671474.

- ^ Nowell, Paul (May 3, 1998). "Furniture firm taps Titanic to stay afloat". Associated Press. Retrieved October 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Moore, Waveney Ann (April 5, 1996). "Movie's popularity elevating value of dollar". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved October 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Lusitania survivor attends Newport Convention". Voyage (43). Titanic International Society: 93, 97. Spring 2003.

- ^ a b "A gentleman to remember". Voyage (48). Titanic International Society. Summer 2004.

- ^ Wilson, Bill (Autumn 2011). "Journey to Titanic's home". Voyage (77). Titanic International Society: 3–6.

- ^ a b Haas, Charles A. (Winter 2012). "A voyage of remembrance". Voyage (82). Titanic International Society: 56–57.

- ^ "A Tribute to the Bandsmen of the Titanic". Voyage (84). Titanic International Society. Summer 2013.

- ^ "Titanic plaque to be dedicated on Dec. 2". Allegro. 116 (10). American Federation of Musicians Local 802. October 2016. Retrieved December 25, 2020.

- ^ "Trustees". Titanic International Society. 14 February 2019. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- ^ Yang, Young Soo. "An enduring fascination with Titanic and its people". NJTV News. NJTV. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ "Jack Eaton (1926-2021)". The Highlands Current. Cold Spring, New York. January 30, 2021. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ "John Paul Eaton May 27, 1926 – January 29, 2021". Titanic International Society. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ^ "White Star's Wonder Ship". Voyage (76). Titanic International Society. Summer 2011.

- ^ "Mystery of the Morro Castle". Voyage (2). Titanic International: 41. October 1989.

- ^ "Lusitania: a view from the stern". Voyage (41). Titanic International Society. Fall 2002.

- ^ "City of Benares — the children's evacuee ship". Voyage (112). Titanic International Society. Summer 2020.

- ^ "QE2 Sails to a New Life". Voyage (66). Titanic International Society. Winter 2008.

- ^ "World's Titanic societies come together to mark liner's 95th anniversary". Voyage (60). Titanic International Society: 149–161. Summer 2007.

- ^ "Journey to Titanic's Home". Voyage (77). Titanic International Society. Autumn 2011.

- ^ "Titanic Society of Atlantic Canada: November 25, 2018 General Meeting". Maritime Museum of the Atlantic. 30 October 2018. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ^ "Titanic International Society 2020 Convention". Titanic International Society. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ^ "Coast Guard commemorates Titanic Centennial in Boston". Coast Guard News. April 10, 2012. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ "RMS TITANIC Memorial Ceremony to be held in Halifax, Nova Scotia April 15". Coast Guard News. April 8, 2010. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ a b Mohn, Tanya (April 7, 2012). "Crossing the Ocean, 1912 vs. 2012". New York Times. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- ^ "Courage and heroism born out of tragedy in the Atlantic". Courier-Post. April 8, 1987. p. 55. Retrieved October 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Identification of Titanic's Unknown Child". Voyage (41). Titanic International Society. Fall 2002.

- ^ "Canadians identify child aboard Titanic". USA Today. July 31, 2007. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ Rourke, Mary (June 1, 2009). "Last living survivor of sinking of the Titanic". Chicago Tribune. p. 18. Retrieved October 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Last Titanic survivor dies at 97". BBC. June 1, 2009. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- ^ Titanic: Destination Disaster: The legends and the reality (2nd ed., 2011). WorldCat. 15 November 2011. ISBN 9780857330253. OCLC 751718514.

- ^ a b "Abandoning the Titanic". Secrets of the Dead. PBS. 6 October 2020. Retrieved November 4, 2020.

- ^ Gainey, Caitlin (August 30, 2019). "Titanic: The Reboot". Scientific American. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

External links

edit- Official website

- British Titanic Society

- Deutscher Titanic-Verein (German Titanic Society, in German)