John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry

John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry[nb 1] was an effort by abolitionist John Brown, from October 16 to 18, 1859, to initiate a slave revolt in Southern states by taking over the United States arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (since 1863, West Virginia). It has been called the dress rehearsal for, or tragic prelude to, the American Civil War.[3]: 5

| John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the prelude to the American Civil War | |||||||

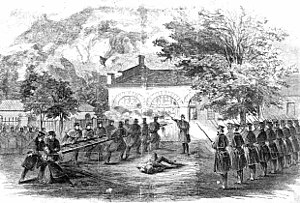

Harper's Weekly illustration of U.S. Marines attacking John Brown's "Fort" | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Abolitionist militias | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| United States Marines | Abolitionist militias | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

U.S. Marines:

|

| ||||||

Civilians:

| |||||||

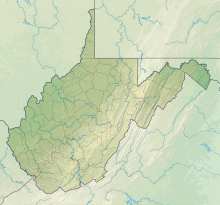

Location within West Virginia | |||||||

- Northwest Ordinance

- Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions

- End of Atlantic slave trade

- Missouri Compromise

- Tariff of 1828

- Nat Turner's Rebellion

- Nullification crisis

- End of slavery in British colonies

- Texas Revolution

- United States v. Crandall

- Gag rule

- Commonwealth v. Aves

- Murder of Elijah Lovejoy

- Burning of Pennsylvania Hall

- American Slavery As It Is

- United States v. The Amistad

- Prigg v. Pennsylvania

- Texas annexation

- Mexican–American War

- Wilmot Proviso

- Nashville Convention

- Compromise of 1850

- Uncle Tom's Cabin

- Recapture of Anthony Burns

- Kansas–Nebraska Act

- Ostend Manifesto

- Bleeding Kansas

- Caning of Charles Sumner

- Dred Scott v. Sandford

- The Impending Crisis of the South

- Panic of 1857

- Lincoln–Douglas debates

- Oberlin–Wellington Rescue

- John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry

- Virginia v. John Brown

- 1860 presidential election

- Crittenden Compromise

- Secession of Southern states

- Peace Conference of 1861

- Corwin Amendment

- Battle of Fort Sumter

Brown's party of 22[1] was defeated by a company of U.S. Marines, led by First Lieutenant Israel Greene.[4] Ten of the raiders were killed during the raid, seven were tried and executed afterwards, and five escaped. Several of those present at the raid would later be involved in the Civil War: Colonel Robert E. Lee was in overall command of the operation to retake the arsenal. Stonewall Jackson and Jeb Stuart were among the troops guarding the arrested Brown,[3] and John Wilkes Booth was a spectator at Brown's execution. John Brown had originally asked Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass, both of whom he had met in his transformative years as an abolitionist in Springfield, Massachusetts, to join him in his raid, but Tubman was prevented by illness and Douglass declined, as he believed Brown's plan was suicidal.[5][6]

The raid was extensively covered in the press nationwide—it was the first such national crisis to be publicized using the new electrical telegraph. Reporters were on the first train leaving for Harpers Ferry after news of the raid was received, at 4 p.m. on Monday, October 17.[7] It carried Maryland militia, and parked on the Maryland side of the Harpers Ferry bridge, just 3 miles (4.8 km) east of the town (at the hamlet of Sandy Hook, Maryland). As there were few official messages to send or receive, the telegraph carried on the next train, connected to the cut telegraph wires, was "given up to reporters", who "are in force strong as military".[8]: 17 By Tuesday morning the telegraph line had been repaired,[8]: 21 and there were reporters from The New York Times "and other distant papers".[8]: 23

Brown's raid caused much excitement and anxiety throughout the United States,[9] with the South seeing it as a threat to slavery and thus their way of life, and some in the North perceiving it as a bold abolitionist action. At first it was generally viewed as madness, the work of a fanatic.[10] It was Brown's words and letters after the raid and at his trial – Virginia v. John Brown – aided by the writings of supporters, including Henry David Thoreau, that turned him into a hero and icon for the Union.

Etymology

editThe label "raid" was not used at the time. A month after the attack, a Baltimore newspaper listed 26 terms used, including "insurrection", "rebellion", "treason", and "crusade". "Raid" was not among them.[3]: 4

Brown's preparation

editJohn Brown rented the Kennedy Farmhouse, with a small cabin nearby, 4 miles (6.4 km) north of Harpers Ferry, in Washington County, Maryland,[11] and took up residence under the name Isaac Smith. Brown came with a small group of men minimally trained for military action. His group eventually included 21 men besides himself (16 white men, five black men). Northern abolitionist groups sent 198 breech-loading .52-caliber Sharps carbines ("Beecher's Bibles"). He ordered from a blacksmith in Connecticut 950 pikes, for use by blacks untrained in the use of firearms, as few were.[12]: 19–20 He told curious neighbors that they were tools for mining, which aroused no suspicion as for years the possibility of local mining for metals had been explored.[13]: 17 Brown "frequently took home with him parcels of earth, which he pretended to analyse in search of minerals. Often his neighbors would visit him when he was making his chemical experiments and so well did he act his part that he was looked upon as one of profound learning and calculated to be a most useful man to the neighborhood."[14]

The pikes were never used; a few blacks in the engine house carried one, but none used it. After the action was over and most of the principals dead or imprisoned, they were sold at high prices as souvenirs. Harriet Tubman had one,[15] and Abby Hopper Gibbons another;[16] the Marines returning to base each had one.[17] When all had been taken or sold, an enterprising mechanic started making and selling new ones.[18] "It is estimated that enough of these have been sold as genuine to supply a large army."[19] Virginian Fire-Eater Edmund Ruffin had them sent to the governors of every slave state, with a label that said "Sample of the favors designed for us by our Northern Brethren". He also carried one around in Washington D.C., showing it to every one he could, "so as to create fear and terror of slave insurrection".[20]

The United States Armory was a large complex of buildings that manufactured small arms for the U.S. Army (1801–1861), with an Arsenal (weapons storehouse) that was thought to contain at the time 100,000 muskets and rifles.[21] However Brown, who had his own stock of weapons, did not seek to capture those of the Arsenal.[22]: 55–56

Brown attempted to attract more black recruits, and felt the lack of a black leader's involvement. He had tried recruiting Frederick Douglass as a liaison officer to the slaves in a meeting held (for safety) in an abandoned quarry at Chambersburg, Pennsylvania.[23] It was at this meeting that ex-slave "Emperor" Shields Green, rather than return home with Douglass (in whose house Green was living), decided to join with John Brown on his attack on the United States Armory, Green stating to Douglass "I believe I will go with the old man." Douglass declined, indicating to Brown that he believed the raid was a suicide mission. The plan was "an attack on the federal government" that "would array the whole country against us. ...You will never get out alive", he warned.[24]

According to Osborne Anderson, "the Old Captain told us, we stood nine chances to one to be killed; but, said the Captain at the same time[,] 'there are moments when men can do more dead than alive.'"[25][26]

The Kennedy Farmhouse served as "barracks, arsenal, supply depot, mess hall, debate club, and home". It was very crowded, and life there was tedious. Brown was worried about arousing neighbors' suspicions. As a result, the raiders had to stay indoors during the daytime, without much to do but study (Brown recommended Plutarch's Lives),[27] drill, argue politics, discuss religion, and play cards and checkers. Brown's daughter-in-law Martha served as cook and housekeeper. His daughter Annie served as lookout. She remarked later that these were the most important months of her life.[28] Brown wanted women at the farm, to prevent suspicions of a large all-male group. The raiders went outside at night to drill and get fresh air. Thunderstorms were welcome since they concealed noise from Brown's neighbors.[29]

Brown did not plan to execute a quick raid and immediately escape to the mountains. Rather, he intended to arm rebellious slaves with the aim of striking terror in the slaveholders in Virginia. Believing that on the first night of action, 200 to 500 slaves would join his line, Brown ridiculed the militia and the regular army that might oppose him. He planned to send agents to nearby plantations, rallying the slaves, and to hold Harpers Ferry for a short time, with the expectation that as many volunteers, white and black, would join him as would form against him. He would then move rapidly southward, sending out armed bands along the way that would free more slaves, obtain food, horses, and hostages, and destroy slaveholders' morale. Brown intended to follow the Appalachian Mountains south into Tennessee and even Alabama, the heart of the South, making forays into the plains on either side.[30]

Advance knowledge of the raid

editBrown paid Hugh Forbes $100 per month (equivalent to $3,270 in 2023),[31] to a total of $600, to be his drillmaster. Forbes was an English mercenary who served Giuseppe Garibaldi in Italy. Forbes' Manual for the Patriotic Volunteer was found in Brown's papers after the raid. Brown and Forbes argued over strategy and money. Forbes wanted more money so that his family in Europe could join him.[32] Forbes sent threatening letters to Brown's backers in an attempt to get money. Failing in this effort, Forbes traveled to Washington, DC, and met with U.S. Senators William H. Seward and Henry Wilson. He denounced Brown to Seward as a "vicious man" who needed to be restrained, but did not disclose any plans for the raid. Forbes partially exposed the plan to Senator Wilson and others. Wilson wrote to Samuel Gridley Howe, a Brown backer, advising him to get Brown's backers to retrieve the weapons intended for use in Kansas. Brown's backers told him that the weapons should not be used "for other purposes, as rumor says they may be".[33]: 248 In response to warnings, Brown had to return to Kansas to shore up support and discredit Forbes. Some historians believe that this trip cost Brown valuable time and momentum.[34]

Another important figure that helped to pay for the raid was Mary Ellen Pleasant. She donated $30,000 (equivalent to $1.1 million in 2023), saying it was the "most important and significant act of her life".[35]

Estimates are that at least eighty people knew about Brown's planned raid in advance, although Brown did not reveal his total plan to anyone. Many others had reasons to believe that Brown was contemplating a move against the South. One of those who knew was David J. Gue of Springdale, Iowa, where Brown had spent time. Gue was a Quaker who believed that Brown and his men would be killed. Gue decided to warn the government "to protect Brown from the consequences of his own rashness". He sent an anonymous letter to Secretary of War John B. Floyd:

Cincinnati, Aug. 20, 1859. SIR: I have lately received information of a movement of so great importance that I feel it to be my duty to impart it to you without delay.

I have discovered the existence of a secret association, having for its object the liberation of the slaves of the South, by a general insurrection. The leader of the movement is "Old John Brown", late of Kansas. He has been in Canada during the winter, drilling the negroes there, and they are only waiting his word to start for the South to assist the slaves. They have one of their leading men (a white man) in an armory in Maryland; where it is situated I am not enabled to learn.

As soon as everything is ready, those of their number who are in the Northern States and Canada are to come in small companies to their rendezvous, which is in the mountains of Virginia. They will pass down through Pennsylvania and Maryland, and enter Virginia at Harper's Ferry. Brown left the North about three or four weeks ago, and will arm the negroes and strike a blow in a few weeks, so that whatever is done must be done at once. They have a large quantity of arms at their rendezvous, and are probably distributing them already. I am not fully in their confidence. This is all the information I can give you.

I dare not sign my name to this, but trust that you will not disregard this warning on that account.[36]

He was hoping that Floyd would send soldiers to Harpers Ferry. He hoped that the extra security would motivate Brown to call off his plans.[33]: 284–285

Even though President Buchanan offered a $250 reward for Brown, Floyd did not connect the John Brown of Gue's letter to the John Brown of Pottawatomie, Kansas, fame. He knew that Maryland did not have an armory (Harpers Ferry is in Virginia, today West Virginia, just across the Potomac River from Maryland.) Floyd concluded that the letter writer was a crackpot, and disregarded it. He later said that "a scheme of such wickedness and outrage could not be entertained by any citizen of the United States".[33]: 285

Brown's second in command John Henry Kagi wrote to a friend on October 15, the day before the attack, that they had heard there was a search warrant for the Kennedy farmhouse, and therefore they had to start eight days sooner than planned.[37]

Timeline of the raid

editSunday, October 16

editOn Sunday night, October 16, 1859, at about 11 PM, Brown left three of his men behind as a rear-guard, in charge of the cache of weapons: his son Owen Brown, Barclay Coppock, and Francis Jackson Meriam. He led the rest across the bridge and into the town of Harpers Ferry, Virginia. Brown detached a party under John Cook, Jr., to capture Colonel Lewis Washington, great-grandnephew of George Washington, at his nearby Beall-Air estate, free his slaves, and seize two relics of George Washington: a sword Lewis Washington said had been presented to George Washington by Frederick the Great, and two pistols given by Marquis de Lafayette, which Brown considered talismans.[38] The party carried out its mission and returned via the Allstadt House, where they took more hostages and freed more slaves.[39]

Brown's men needed to capture the Armory and then escape before word could be sent to Washington. The raid was going well for Brown's men. They cut the telegraph line twice, to prevent communication in either direction: first on the Maryland side of the bridge; slightly later on the far side of the station, preventing communication with Virginia.

Some of Brown's men were posted so as to control both the Potomac and the Shenandoah bridges. Others went into the town; it was the middle of the night and a single watchman was the only person at the Armory. He was unarmed and forced to turn over his keys when some of Brown's men appeared and threatened him.

Brown had been sure that he would get major support from slaves ready to rebel; his followers said to a man that he had told them that. But Brown had no way to inform these slaves; they did not arrive, and Brown waited too long for them. The South, starting with Governor Wise, whose speech after Harpers Ferry was reprinted widely, proclaimed that this showed the truth of their old allegation, that their slaves were happy and did not want freedom. Osborne Anderson, the only raider to leave a memoir, and the only black survivor, put the lie to this:

The Sunday evening of the outbreak, when we visited the plantations and acquainted the slaves with our purpose to effect their liberation, the greatest enthusiasm was manifested by them—joy and hilarity beamed from every countenance. One old mother, white-haired from age, and borne down with the labors of many years in bonds, when told of the work in hand, replied: "God bless you! God bless you! " She then kissed the party at her house, and requested all to kneel, which we did, and she offered prayer to God for His blessing on the enterprise, and our success. At the slaves' quarters, there was apparently a general jubilee, and they stepped forward manfully, without impressing or coaxing.[40]: 39

Monday, October 17

editA free black man was the first fatality to result from the raid: Heyward Shepherd, a baggage handler at the Harpers Ferry train station, who had ventured out onto the bridge to look for a watchman who had been driven off by Brown's raiders.[41][42] He was shot from behind when he by chance encountered the raiders, refused to freeze, and headed back to the station.[43] That a black man was the first casualty of an insurrection whose purpose was to aid blacks, and that he disobeyed the raiders, made him a hero of the "Lost Cause" pro-Confederacy movement; a monument enshrining this perspective on Shepherd's death was installed in 1931.[44] But in fact, Shepherd was only making "an effort to see what was going on".[45]

The shot and a cry of distress were heard by physician John Starry, who lived across the street from the bridge and walked over to see what was happening. After he saw it was Shepherd and that he could not be saved, Brown let him leave. Instead of going home he started the alarm, having the bell on the Lutheran church rung, sending a messenger to summon help from Charles Town, and then going there himself, after having notified such local men as could be contacted quickly.[46]: Testimony 23–25

The Baltimore & Ohio train

editAbout 1:15 AM the eastbound Baltimore & Ohio express train from Wheeling—one per day in each direction[47]—was to pass through towards Baltimore. The night watchman ran to warn of trouble ahead; the engineer stopped and then backed up the train.[48] Two train crew members who stepped down to reconnoiter were shot at.[49]: 316 Brown boarded the train and talked with passengers for over an hour, not concealing his identity. (Because of his abolitionist work in Kansas, Brown was a "notorious" celebrity;[50][51] he was well known to any newspaper reader.) Brown then told the train crew they could continue. According to the conductor's telegram they had been detained for five hours,[8]: 5 but according to other sources the conductor did not think it prudent to proceed until sunrise, when it could more easily be verified that no damage had been done to the tracks or bridge, and that no one would shoot at them.[49]: 317 [52][53][54] The passengers were cold on the stopped train, with the engine shut down; normally the temperature would have been around 5 °C (41 °F),[55] but it was "unusually cold".[56]: 8 Brown's men had blankets over their shoulders and arms;[56]: 12 John Cook reported later having been "chilled through".[57]: 12 The passengers were allowed to get off and they "went into the hotel and remained there, in great alarm, for four or five hours".[58]: 175

Several times, Brown later called this incident his "one mistake": "not detaining the train on Sunday night or else permitting it to go on unmolested".[59][60] Brown scholar Louis DeCaro Jr. called it a "ruinous blunder".[22]: 34

The train departed at dawn, Brown himself, on foot, escorting the train across the bridge.[22]: 34 At about 7 AM it arrived at the first station with a working telegraph,[61] Monocacy, near Frederick, Maryland, about 23 miles (37 km) east of Harpers Ferry. The conductor sent a telegram to W. P. Smith, Master of Transportation at B&O headquarters in Baltimore. Smith's reply to the conductor rejected his report as "exaggerated", but by 10:30 AM he had received confirmation from Martinsburg, Virginia, the next station west of Harpers Ferry. No westbound trains were arriving and three eastbound trains were backed up on the Virginia side of the bridge;[58]: 181 because of the cut telegraph line the message had to take a long, roundabout route via the other end of the line in Wheeling, and from there back east via Pittsburgh, causing delay.[8]: 7, 15 At that point Smith informed the railroad president, John W. Garrett, who sent telegrams to Major General George H. Steuart of the First Light Division, Maryland Volunteers, Virginia Governor Henry A. Wise, U.S. Secretary of War John B. Floyd, and U.S. President James Buchanan.[8]: 5–9

Armory employees taken hostage

editAt about this time Armory employees began arriving for work; they were taken as hostages by Brown's party. Reports differ on how many there were, but there were many more than would fit in the small engine house. Brown divided them into two groups, keeping only the ten most important in the engine house;[56]: 17–18 the others were held in a different Armory building. According to the report of Robert E. Lee,[62] the hostages included:

- Colonel L. W. Washington, of Jefferson County, Virginia

- Mr. J. H. Allstadt, of Jefferson County, Virginia

- Mr. Israel Russell, Justice of the Peace, Harpers Ferry

- Mr. John Donahue, clerk of Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

- Mr. Terence Byrne, of Maryland

- Mr. George D. Shope, of Frederick, Maryland

- Mr. Benjamin Mills, master armorer [weaponmaker], Harpers Ferry Arsenal

- Mr. A. M. Ball, master machinist, Harpers Ferry Arsenal

- Mr. John E.P. Daingerfield or Dangerfield, paymaster's clerk, Acting Paymaster, Harpers Ferry Arsenal, not to be confused with Dangerfield Newby. Brown told him that by noon he would have 1,500 armed men with him.[63]: 266

- Mr. J. Burd, armorer, Harpers Ferry Arsenal

All save the last were held in the engine house.[64]: 446 According to a newspaper report, there were "not less than sixty"; another report says "upwards of seventy".[56]: 13 they were detained in "a large building further down the yard".[65] The number of rebels sometimes was inflated because some observers, who had to remain at a distance, thought that the hostages were part of Brown's party.[56]: 15

Armed citizens arrive

editAs it became known that citizens had been taken hostage by an armed group, men of Harpers Ferry found themselves without arms other than fowling-pieces, which were useless at a distance.

Military companies from neighboring towns began to arrive late Monday morning.[66] Among them was Captain John Avis, who would soon be Brown's jailor, who arrived with a company of militia from Charles Town.[67]

Also according to the report of Lee, who does not mention Avis, the following volunteer militia groups arrived between 11 AM and his arrival in the evening:

- Jefferson Guards and volunteers from Charles Town, under Captain J. W. Rowen

- Hamtramck Guards, Jefferson County, Captain V. M. Butler

- Shepherdstown troop, Captain Jacob Rienahart

- Captain Ephraim G. Alburtis's company, by train from Martinsburg. Most of the militia members were employees of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad shops there. They freed all the hostages except those in the engine house.[65][68]: 33 [69]

- Captain B. B. Washington's company from Winchester

- Three companies from Fredericktown, Maryland, under Colonel Shriver

- Companies from Baltimore, under General Charles C. Edgerton, second light brigade

Expecting that thousands of slaves would join him,[70][8]: 19 Brown stayed too long in Harpers Ferry.[49]: 311 Harpers Ferry is on a narrow peninsula, almost an island;[71]: xix it is sometimes called "the Island of Virginia".[13]: 7, 35, 55 By noon hopes of escape were gone, as his men had lost control of both bridges leading out of town, which because of the terrain were the only practical escape routes.[49]: 319 The other bridge, of which not even the pillars remain (the visible pillars are from a later bridge), went east over the Shenandoah River from Harpers Ferry.

The militia companies, under the direction of Colonels R. W. Baylor and John T. Gibson, forced the insurgents to abandon their positions and, since escape was impossible, fortify themselves in "a sturdy stone building",[4]: 565 the most defensible in the Armory,[72] the fire engine house, which would be known later as John Brown's Fort. (There were two fire engines;[73] which Greene described as old-fashioned and heavy, plus a hose cart.[4]: 565 [7]) They blocked the few windows, used the engines and hose cart to block the heavy doors, and reinforced the doors with rope, making small holes on the walls and through them trading sporadic gunfire with the surrounding militia. Between 2 and 3 there was "a great deal of firing".[40]: 345

During the day four townspeople were killed, including the mayor, who managed the Harpers Ferry station and was a former county sheriff. Eight militiamen were wounded. But the militia, besides the poor quality of their weapons, were disorderly and unreliable.[12]: 22 "Most of them [militiamen] got roaring drunk."[74] "A substantial proportion of the militia (along with many of the townspeople) had become a disorganized, drunken, and cowering mob by the time that Colonel Robert E. Lee and the U.S. Marines captured Brown on Tuesday, October 18." The Charleston Mercury called it a "broad and pathetic farce". According to several reports, Governor Wise was outraged at the poor performance of the local militia.[12]: 21

At one point Brown sent out his son Watson and Aaron Dwight Stevens with a white flag, but Watson was mortally wounded by a shot from a town man, expiring after more than 24 hours of agony, and Stevens was shot and taken prisoner. The raid was clearly failing. One of Brown's men, William H. Leeman, panicked and made an attempt to flee by swimming across the Potomac River, but he was shot and killed while doing so. During the intermittent shooting, another son of Brown, Oliver, was also hit; he died, next to his father, after a brief period.[75] Brown's third participating son, Owen, escaped (with great difficulty) via Pennsylvania to the relative safety of his brother John Jr.'s house in Ashtabula County in northeast Ohio,[76] but he was not part of the Harpers Ferry action; he was guarding the weapons at their base, the Kennedy Farm, just across the river in Maryland.

Buchanan calls out the Marines

editLate in the afternoon President Buchanan called out a detachment of U.S. Marines from the Washington Navy Yard, the only federal troops in the immediate area: 81 privates, 11 sergeants, 13 corporals, and 1 bugler, armed with seven howitzers.[77] The Marines left for Harper's Ferry on the regular 3:30 train, arriving about 10 PM.[4]: 564 [72] Israel Greene was in charge.

To command them Buchanan ordered Brevet Colonel[71]: xv Robert E. Lee, conveniently on leave at his home, just across the Potomac in Arlington, Virginia, to "repair" to Harpers Ferry,[71][78] where he arrived about 10 PM, on a special train.[4]: 564 [79] Lee had no uniform readily available, and wore civilian clothes.[4]: 567 [80]

Tuesday, October 18

editThe Marines break through the engine house door

editAt 6:30 AM Lee began the attack on the engine house.[4]: 565 He first offered the role of attacking it to the local militia units, but both commanders declined. Lee then sent Lt. J. E. B. Stuart, serving as a volunteer aide-de-camp, under a white flag of truce to offer John Brown and his men the option of surrendering. Colonel Lee informed Lt. Israel Greene that if Brown did not surrender, he was to direct the Marines to attack the engine house. Stuart walked towards the front of the engine house where he told Brown that his men would be spared if they surrendered. Brown refused and as Stuart walked away, he made a pre-arranged signal—waving his hat—to Lt. Greene and his men standing nearby.[4]: 565

Greene's men then tried to break in using sledgehammers, but their efforts were unsuccessful. He found a ladder nearby, and he and about twelve Marines used it as a battering ram to break down the sturdy doors. Greene was the first through the door and with the assistance of Lewis Washington, identified and singled out John Brown. Greene later recounted what events occurred next:

Quicker than thought I brought my saber down with all my strength upon [Brown's] head. He was moving as the blow fell, and I suppose I did not strike him where I intended, for he received a deep saber cut in the back of the neck. He fell senseless on his side, then rolled over on his back. He had in his hand a short Sharpe's cavalry carbine. I think he had just fired as I reached Colonel Washington, for the Marine who followed me into the aperture made by the ladder received a bullet in the abdomen, from which he died in a few minutes. The shot might have been fired by someone else in the insurgent party, but I think it was from Brown. Instinctively as Brown fell I gave him a saber thrust in the left breast. The sword I carried was a light uniform weapon, and, either not having a point or striking something hard in Brown's accouterments, did not penetrate. The blade bent double.[4]: 566

Two of the raiders were killed, and the rest taken prisoner. Brown was wounded before and after his surrender.[22]: 38–39 The hostages were freed and the assault was over. It lasted three minutes.[4]: 567

According to one marine, the raiders presented a sad appearance:

Some were wounded and others dead or dying. They were greeted with execrations, and only the precautions that had been taken, saved them from the exasperated crowd, many of whom had relatives killed or wounded by the desperate gang of cut-throats. Nearly every man carried a gun, and the cry of "Shoot them! Shoot them!" rang on every side. Only the steadiness of the trained marines, under the command of that great soldier Robert E. Lee, then an unknown colonel of the United States Army, prevented the butchery of the entire gang of outlaws.[64]: 442

Colonel Lee and Jeb Stuart searched the surrounding country for fugitives who had participated in the attack. Few of Brown's associates escaped, and among the five who did, some were sheltered by abolitionists in the North, including William Still.[81][82]

Interviews

editAll the bodies were taken out and laid on the ground in front. "A detail of [Greene's] men" carried Brown and Edwin Coppock, the only other white survivor of the attack on the engine house, to the adjacent office of the paymaster,[4]: 568 where they lay on the floor for over a day. Until they went with the group to the Charles Town jail on Wednesday, there is no record of the location of the two surviving captured black raiders, Shields Green and John Anthony Copeland, who were also the only two survivors of the engine house with no injuries. Green attempted unsuccessfully to disguise himself as one of the enslaved of Colonel Washington being liberated.

From this point forward, Brown would endlessly be interrogated by soldiers, politicians, lawyers, reporters, citizens, and preachers.[22]: 42 He welcomed the attention.

The first to interview him was Virginia congressman Alexander Boteler, who rode over from his home in nearby Shepherdstown, West Virginia, and was present when Brown was carried out of the engine house, and told a Catholic priest to leave.[83][22]: 49 Five people, in addition to several reporters, came almost immediately to Harpers Ferry specifically to interview Brown. He was interviewed at length as he lay there over 24 hours; he had been without food and sleep for over 48 hours.[84] ("Brown carried no provisions on the expedition, as if God would rain down manna from the skies as He had done for the Israelites in the wilderness."[85]) The first interviewers after Boteler were Virginia Governor Wise, his attorney Andrew Hunter, who was also the leading attorney in Jefferson County, and Robert Ould, United States Attorney for the District of Columbia, sent by President Buchanan.[86] Governor Wise having left—he set up a base in a Harpers Ferry hotel—Brown was then interviewed by Senator James M. Mason, from Winchester, Virginia, and Representatives Charles J. Faulkner, from Martinsville, Virginia, and Copperhead Clement Vallandigham, from Ohio.[58]: 197 (Brown lived for years in Ohio, and both Watson and Owen Brown were born there.) Vallandingham was on his way from Washington to Ohio via the B&O Railroad, which of course would take him through Harpers Ferry. In Baltimore he was informed about the raid.[87]

Up until this point, most public opinion in the North and West had seen Brown as a fanatic, a crazy man, attacking Virginia with only 22 men, of whom 10 were killed immediately, and 7 others would soon be hanged, as well as 5 deaths and 9 injuries among the Marines and local population. With the newspaper reports of these interviews, followed by Brown's widely reported words at his trial, the public perception of Brown changed suddenly and dramatically. According to Henry David Thoreau, "I know of nothing so miraculous in our history. Years were not required for a revolution of public opinion; days, nay hours, produced marked changes."[88]

Governor Wise, though firmly in favor of Brown's execution, called him "the gamest man I ever saw".[89][58]: 198 Boteler also spoke well of him.[83] Representative Vallandingham, described later by Thoreau as an enemy of Brown,[90] made the following comment after reaching Ohio:

It is in vain to underrate either the man or the conspiracy. Captain John Brown is as brave and resolute a man as ever headed an insurrection, and in a good cause, and with a sufficient force, would have been a consummate partisan commander. He has coolness, daring, persistency, the stoic faith and patience, and a firmness of will and purpose unconquerable. He is tall, wiry, muscular, but with little flesh—with a cold, gray eye, gray hair, beard and mustache, compressed lips and sharp, aquiline nose; of cast-iron face and frame, and with powers of endurance equal to anything needed to be done or suffered in any cause. Though engaged in a wicked, mad and fanatical enterprise, he is the farthest possible remove from the ordinary ruffian, fanatic, or madman; but his powers are rather executory than inventive, and he never had the depth or breadth of mind to originate and contrive himself the plan of insurrection which he undertook to carry out. The conspiracy was, unquestionably, far more extended than yet appears, numbering among the conspirators many more than the handful of followers who assailed Harpers Ferry, and having in the North and West, if not also the South, as its counselors and abettors, men of intelligence, position and wealth. Certainly it was one of the best planned and best executed conspiracies that ever failed.[91][58]: 204

Like Mason (see below), Vallandingham thought Brown could not possibly have thought of and planned the raid by himself.

Interview by Governor Wise

editVirginia Governor Wise, with a force of ninety men,[58]: 183 who were disappointed that the action was already over,[58]: 194 arrived from Richmond about midday Tuesday.[92]: 176 n. 24 [93] "Learning how quickly the Marines had crushed the raid, Wise 'boiled over', and said he would rather have lost both legs and both arms from his shoulders and hips than such a disgrace should have been cast upon it [Virginia, since Brown held off all the local militia]. That fourteen white men and five negroes should have captured the government works and all Harper's Ferry, and have found It possible to retain them for [even] one hour, while Col. Lee, with twelve marines, settled the matter in ten minutes."[94][58]: 194

Wise interviewed Brown while he, along with Stevens, was lying on the floor of the paymaster's office at the Arsenal, where they would remain until, over thirty hours later, they were moved to the Jefferson County jail.[58]: 205 Brown, despite his wounds, was "courteous and afable".[58]: 204 Andrew Hunter took notes,[95]: 167 [58]: 194 but there is no transcript of this interview. One exchange was as follows:

Wise. Mr. Brown, the silver of your hair is reddened by the blood of crime, and you should eschew these hard words and think upon eternity. You are suffering from wounds, perhaps fatal; and should you escape death from these causes, you must submit to a trial which may involve death. Your confessions justify the presumption that you will be found guilty; and even now you are committing a felony under the laws of Virginia, by uttering sentiments like these. It is better you should turn your attention to your eternal future than be dealing in denunciations which can only injure you.

Brown. Governor, I have from all appearances not more than fifteen or twenty years the start of you in the journey to that eternity of which you kindly warn me; and whether my time here shall be fifteen months, or fifteen days, or fifteen hours, I am equally prepared to go. There is an eternity behind and an eternity before; and this little speck in the centre, however long, is but comparatively a minute. The difference between your tenure and mine is trifling, and I therefore tell you to be prepared. I am prepared. You all have a heavy responsibility, and it behooves you to prepare more than it does me.[96]: 571

The paymaster's clerk at the Arsenal, Captain J.E.P. Dangerfield (not to be confused with Dangerfield Newby), was taken hostage when he arrived for work. He was present at this interview, and remarked that: "Governor Wise was astonished at the answers he received from Brown."[96]: 559 Back in Richmond, on Saturday, October 22, in a speech widely reported in the newspapers, Wise himself stated:

They are themselves mistaken who take him to be a madman. He is a bundle of the best nerves I ever saw, cut and thrust, bleeding and in bonds. He is a man of clear head, of courage, fortitude and simple ingenuousness. He is cool, collected and indomitable, and it is but just to him to say, that he was humane to his prisoners, as attested to me by Col. Washington and Mr. Mills; and he inspired me with great trust in his integrity, as a man of truth. He is a fanatic, vain and garrulous, but firm, and truthful, and intelligent.[97][98][99]

Wise also reported the opinion of Lewis Washington, in a passage called "well known" in 1874: "Colonel Washington says that he, Brown, was the coolest and firmest man he ever saw in defying danger and death. With one son dead by his side, and another shot through, he felt the pulse of his dying son with one hand and held his rifle with the other, and commanded his men with the utmost composure, encouraging them to be firm, and to sell their lives as dearly as they could."[99][98]

Wise left for his hotel in Harpers Ferry about dinnertime Tuesday.

Interview by Senator Mason and two Representatives

editVirginia Senator James M. Mason lived in nearby Winchester, and would later chair the Select Senate committee investigating the raid.[76]: 343 He also came immediately to Harpers Ferry to interview Brown. Congressmen Clement Vallandigham of Ohio, who called Brown "sincere, earnest, practical",[100] Charles J. Faulkner of Virginia, Robert E. Lee,[46]: 46 and "several other distinguished gentlemen" were also present. The audience averaged 10 to 12. Lee said that he would exclude all visitors from the room if the wounded men were annoyed or pained by them, but Brown said he was by no means annoyed; on the contrary, he was glad to be able to make himself and his motives "clearly understood".[101]

I claim to be here in carrying out a measure I believe perfectly justifiable, and not to act the part of an incendiary or ruffian, but to aid those suffering great wrong. I wish to say furthermore, that you had better—all you people at the South—prepare yourselves for a settlement of that question that must come up for settlement sooner than you are prepared for it. The sooner you are prepared the better. You may dispose of me very easily. I am nearly disposed of now; but this question is still to be settled—this negro question I mean; the end of that is not yet.[101]

A reporter-stenographer of the New York Herald produced a "verbatim" transcript of the interview, although it started before he arrived, shortly after 2 PM. Published in full or part in many newspapers, it is the most complete public statement we have of Brown about the raid.[101]

Wednesday, October 19

editLee and the Marines, except for Greene, left Harper's Ferry for Washington on the 1:15 AM train, the only express east. He finished his report and sent it to the War Department that day.

He made a synopsis of the events that took place at Harpers Ferry. According to Lee's report: "the plan [raiding the Harpers Ferry Arsenal] was the attempt of a fanatic or madman." Lee also believed that the blacks in the raid were forced by Brown. "The blacks, whom he [John Brown] forced from their homes in this neighborhood, as far as I could learn, gave him no voluntary assistance." Lee attributed John Brown's "temporary success" to the panic and confusion and to "magnifying" the number of participants involved in the raid. Lee said that he was sending the Marines back to the Navy Yard. [62]

"Governor Wise is still [Wednesday] here busily engaged in a personal investigation of the whole affair, and seems to be using every means for bringing to retribution all the participators in it."[102]

A holograph copy of Brown's Provisional Constitution, held by the Yale University Library, bears the handwritten annotation: "Handed to Gov. Wise by John Brown on Wed Oct 19/59 before he was removed from the U.S. grounds at Harpers Ferry & while he lay wounded on his cot."[103]

On Wednesday evening the prisoners were moved by train from Harpers Ferry to Charles Town, where they were placed in the Jefferson County jail, "a very pretty jail, ...like a handsome private residence", the press reported.[104] Governor Wise and Andrew Hunter, his attorney, accompanied them.[58]: 205 The Jefferson County jail was "a meek-looking edifice, [which] must have been a respectable private residence".[105] Brown wrote his family: "I am supplied with almost everything I could desire to make me comfortable".[106] According to the New York Tribune's reporter on the scene:

Brown is as comfortably situated as any man can be in jail. He has a pleasant room, which is shared by Stephens [sic], whose recovery remains doubtful. He has opportunities of occupying himself by writing and reading. His jailor, Avis, was of the party who assisted in capturing him. Brown says Avis is one of the bravest men he ever saw, and that his treatment is precisely what be should expect from so brave a fellow. He is permitted to receive such visitors as he desires to see. He says that he welcomes every one, and that he is preaching, even in jail, with great effect, upon the enormities of Slavery, and with arguments that everybody fails to answer. His friends say, with regret, that in many of his recent conversations, he has given stronger reason for a belief that he is insane than ever before. Brown's wounds, excepting one cut on the back of the head, have all now healed.[105]

Trial and execution

editBrown was hastily processed by the legal system. He was charged by a grand jury with treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia, murder, and inciting a slave insurrection. A jury found him guilty of all charges; he was sentenced to death on November 2, and after a legally required delay of 30 days he was hanged on December 2. The execution was witnessed by actor John Wilkes Booth, who later assassinated President Abraham Lincoln. At the hanging and en route to it, authorities prevented spectators from getting close enough to Brown to hear a final speech. He wrote his last words on a scrap of paper given to his jailer Capt. John Avis, whose treatment Brown spoke well of in his letters:

I John Brown am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty, land: will never be purged away; but with Blood. I had as I now think: vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed; it might be done.[3]: 256

Four other raiders were executed on December 16 and two more on March 16, 1860.

In his last speech, at his sentencing, he said to the court:

[H]ad I so interfered in behalf of the rich, the powerful, the intelligent, the so-called great, or in behalf of any of their friends, either father, mother, brother, sister, wife, or children, or any of that class, and suffered and sacrificed what I have in this interference, it would have been all right; and every man in this court would have deemed it an act worthy of reward rather than punishment.[3]: 212

Southerners had a mixed attitude towards their slaves. Many Southern whites lived in constant fear of another slave insurrection; paradoxically, Southern whites also claimed that slaves were content in bondage, blaming slave unrest on Northern abolitionists. After the raid Southerners initially lived in fear of slave uprisings and invasion by armed abolitionists. The South's reaction entered the second phase at around the time of Brown's execution. Southerners were relieved that no slaves had volunteered to help Brown, as they were incorrectly told by Governor Wise and others see (John Brown's raiders), and felt vindicated in their claims that slaves were content. After Northerners had expressed admiration for Brown's motives, with some treating him as a martyr, Southern opinion evolved into what James M. McPherson called "unreasoning fury".[107]

The first Northern reaction among antislavery advocates to Brown's raid was one of baffled reproach. Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, "committed to the methods of nonviolent moral suasion", called the raid "misguided, wild, and apparently insane".[108][109] But through the trial and his execution, Brown was transformed into a martyr. Henry David Thoreau, in A Plea for Captain John Brown, said, "I think that for once the Sharps' rifles and the revolvers were employed in a righteous cause. The tools were in the hands of one who could use them," and said of Brown, "He has a spark of divinity in him."[110] To the South, Brown was a murderer who wanted to deprive them of their property (slaves). The North "has sanctioned and applauded theft, murder, and treason", said De Bow's Review.[49]: 340 [111] According to the Richmond Enquirer, the South's reaction was "horror and indignation".[112] But this was not the entire story. Kent Blaser writes that "there was surprisingly little fear or panic over race insurrection in North Carolina.... Much was made of the refusal of slaves to join in the insurrection".[113]

The Republican Party, faced with charges that their opposition to slavery inspired Brown's raid, distanced themselves from Brown by instead suggesting that it was instead precedented by Democrats' support for filibusters such as William Walker and Narciso López, arguing that their attempts to overthrow foreign governments and their receipt of support from Democratic politicians had inspired Brown to attempt a similar action.[114]

Consequences of Brown's raid

editJohn Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry was the last major event that led to the Civil War (see sidebar, above). According to the Richmond Enquirer, "The Harper's Ferry invasion has advanced the cause of Disunion, more than any other event that has happened since the formation of the Government; it has rallied to that standard men who formerly looked upon it with horror; it has revived, with ten fold [sic] strength the desire of a Southern Confederacy."[112]

His well-publicized raid, a complete failure in the short term, contributed to Lincoln's election in 1860, and Jefferson Davis "cited the attack as grounds for Southerners to leave the Union, 'even if it rushes us into a sea of blood.'"[3]: 5 Seven Southern states seceded to form the Confederacy. The Civil War followed, and four more states seceded; Brown had seemed to be calling for war in his last message before his execution: "the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away, but with Blood."[115]

However, David S. Reynolds wrote, "The raid on Harpers Ferry helped dislodge slavery, but not in the way Brown had foreseen. It did not ignite slave uprisings throughout the South. Instead, it had an immense impact because of the way Brown behaved during and after it, and the way it was perceived by key figures on both sides of the slavery divide. The raid did not cause the storm. John Brown and the reaction to him did".[49]: 309

Brown's raid, trial, and execution energized both the abolitionists in the North and the supporters of slavery in the South, and it brought a flurry of political organizing. Public meetings in support of Brown, sometimes also raising money for his family, were held across the North.[116] "These meetings gave the era's most illustrious thinkers and activists an opportunity to renew their assault on slavery".[117]: 26 It reinforced Southern sentiment for secession.

Casualties

editJohn Brown's raiders

editCounting John Brown, there were 22 raiders, 15 white and 7 black. 10 were killed during the raid, 7 were tried and executed afterwards, and 5 escaped. In addition, Brown was assisted by at least two local enslaved people; one was killed and the other died in jail.

Other casualties, civilian and military

edit- Killed

- Heyward Shepherd, a free African-American B&O baggage master. He was buried in the African-American cemetery on Rt. 11 in Winchester, Virginia. In 1932 no one could find his grave.[118]: 11

- Private Luke Quinn, U.S. Marines, was killed during the storming of the engine house. He was buried in Harpers Ferry Catholic Cemetery on Rte. 340.

- Thomas Boerly, townsperson. According to Richard Hinton, "Mr. Burleigh" was killed by Shields Green.[119]: 305

- George W. Turner, townsperson.

- Fontaine Beckham, Harpers Ferry mayor, B&O stationmaster, former sheriff. Mayor Beckham's Will Book called for the liberation of Isaac Gilbert, Gilbert's wife, and their three children upon his death. When Edwin Coppock killed Beckham the enslaved family was thus freed.[33]: 296

- A man enslaved by Colonel Washington was killed.

- A man enslaved by hostage John Allstad was killed. Both slaves voluntarily joined Brown's raiders. One was killed trying to escape across the Potomac River; the other was wounded and later died in the Charles Town jail.

- Wounded but survived

- Private Matthew Ruppert, U. S. Marines, was shot in the face during the storming of the engine house.

- Edward McCabe, Harpers Ferry laborer.

- Samuel C. Young, Charles Town militia. As he was "permanently disabled by a wound received in defence of Southern institutions" (slavery), a pamphlet was published to raise money for him.[57]

- Martinsburg, Virginia, militia:

- George Murphy

- George Richardson

- G. N. Hammond

- Evan Dorsey

- Nelson Hooper

- George Woollett[3]: 292

Legacy

editMany of John Brown's homes are today small museums. John Brown is featured in an extremely large mural (11'6" tall and 31' long)[120] painted in the Kansas State Capitol in Topeka, Kansas. In "Tragic Prelude", by Kansan John Steuart Curry, the larger-than-life figure of John Brown dominates a scene of war, death, and destruction. Wildfires and a tornado are backdrops to his zeal and fervor. The only major street anywhere named for John Brown is in Port-au-Prince, Haiti (where there is also an Avenue Charles Sumner). In Harpers Ferry today, the engine house, known today as John Brown's Fort, sits in a park, open to walk through, where there is an interpretive display summarizing the events.

Another monument is the cenotaph to three black participants, in Oberlin, Ohio.

Bell from Harper's Ferry Armory

editThe John Brown Bell, taken by the Marborough unit of Massachusetts Volunteer Militia to Marlborough, Massachusetts, has been called the "second-most important bell in American history".[121]

Harpers Ferry National Historical Park

editJust as in the town of Harpers Ferry, John Brown and the raid are downplayed at the Harpers Ferry National Historical Park. Harpers Ferry and some surrounding areas were designated as a National Monument in 1944. Congress later designated it as the Harpers Ferry National Historical Park in 1963.

Grave site

editJohn Brown is buried on his farm near Lake Placid, New York. It is maintained as the New York John Brown Farm State Historic Site. His son Watson is also buried there, and the bones of his son Oliver and nine other raiders are buried in a single coffin.

Conflicting interpretations

editThis section is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (September 2020) |

From 1859 until the assassination of President Lincoln in 1865, Brown was the most famous American. He was the symbol of the nation's polarization: in the North he was a hero, and the day of his execution a day of mourning for many; flags were flown at half staff in some cities. To white Southerners, he was an outlaw, a traitor, promoting slave insurrection.

Doubt has been raised as to whether Brown believed his implausible, undermanned attack could succeed, or whether he knew it was doomed yet wanted the publicity it would generate for the abolitionist cause. Certainly he "fail[ed] to take the steps necessary"[3]: 239 to make it succeed: he never called on nearby slaves to join the uprising, for example.[3]: 236 According to Garrison, "His raid into Virginia looks utterly lacking in common sense—a desperate self-sacrifice for the purpose of giving an earthquake shock to the slave system, and thus hastening the day for a universal catastrophe."[3]: 234 Brown's Provisional Constitution, of which he had stacks of copies printed, "was not just a governing document. It was a scare tactic".[3]: 238

As Brown wrote in 1851: "The trial for life of one bold and to some extent successful man, for defending his rights in good earnest, would arouse more sympathy throughout the nation than the accumulated wrongs and suffering of more than three millions of our submissive colored population."[3]: 240 According to his son Salmon, fifty years later: "He wanted to bring on the war. I have heard him talk of it many times."[3]: 238 Certainly Brown saw to it that his arrest, trial, and execution received as much publicity as possible. He "ask[ed] that the incendiary constitution he carried with him be read aloud".[3]: 240 "He seemed very fond of talking."[3]: 240 Authorities deliberately prevented spectators from being close enough to Brown to hear him speak during his short trip to the gallows, but he did give what became his famous final message to a jailer who had asked for his autograph.[3]: 256

See also

edit- Bleeding Kansas

- John Brown's body, about his funeral in North Elba

- John Brown's Body (song)

- John Brown's Fort

- John Brown's last speech

- John Brown's Provisional Constitution

- John Brown's raiders

- The Last Moments of John Brown (painting)

- List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States

- List of sources for John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry

- Origins of the American Civil War

- Virginia v. John Brown

- Mary Ellen Pleasant

Notes

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry". History.com. Archived from the original on April 1, 2015. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- ^ For example, "Col. Robert E. Lee's Report Concerning the Attack at Harper's Ferry, October 19, 1859"; Horace Greeley, The American Conflict: A History of the Great Rebellion in the United States of America, 1860–64. Volume: 1 (1866). p. 279; French Ensor Chadwick, Causes of the Civil War, 1859–1861 (1906) p. 74; Allan Nevins, The Emergence of Lincoln (1950) vol. 2 ch. 3; James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (1988), p. 201; Stephen W. Sears, Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam (2003) p. 116.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Horwitz, Tony (2011). Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid That Sparked the Civil War. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-0805091533.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Green[e], Israel (December 1885). "The Capture of John Brown". North American Review: 564–569. Archived from the original on January 23, 2021. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- ^ Taylor, Marian (2004). Harriet Tubman: Antislavery Activist. Chelsea House Publishers. pp. 68–69. ISBN 978-0-7910-8340-6.

- ^ Blight, David W. Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018, p. 302.

- ^ a b "The Late Rebellion". The Daily Exchange (Baltimore, Maryland). October 19, 1859. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 1, 2020. Retrieved December 28, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g Baltimore & Ohio Railroad (1860). Correspondence relating to the Insurrection at Harper's Ferry, 17th October, 1859. Annapolis: Senate of Maryland.

- ^ "Insurrection at Harper's Ferry". Anti-Slavery Reporter and Aborigines' Friend. Vol. 7, no. 12. December 1, 1859. pp. 271–272, at p. 272.

- ^ Griffin, Charles J. G. (Fall 2009). "John Brown's 'Madness'". Rhetoric and Public Affairs. 12 (3): 369–388. doi:10.1353/rap.0.0109. JSTOR 41940446. S2CID 144917657.

- ^ "The Kennedy Farmhouse" Archived August 22, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, John Brown website

- ^ a b c Simpson, Craig (Fall 1978). "John Brown and Governor Wise: A New Perspective on Harpers Ferry". Biography. 1 (4): 15–38. doi:10.1353/bio.2010.0765. JSTOR 23539029. S2CID 159682875.

- ^ a b Barry, Joseph (1869). The annals of Harper's Ferry, from the establishment of the national armory in 1794 to the present time, 1869. Hagerstown, Maryland: Hagerstown, Md., Dechert & co. printers.

- ^ "Highly Important Details". Charleston Daily Courier (Charleston, South Carolina). October 22, 1859. p. 1. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved November 14, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Venet, Wendy Hamand (1995). "'Cry Aloud and Spare Not': Northern Antislavery Women and John Brown's Raid". In Finkleman, Paul (ed.). His Soul Goes Marching On. Responses to John Brown and the Harpers Ferry Raid. Charlottesville, Virginia: University Press of Virginia. pp. 98–115, ar p. 99. ISBN 0813915368.

- ^ Gibbons, Abby Hopper; Emerson, Sarah Hopper Gibbons (1896). Life of Abby Hopper Gibbons. Told chiefly through her correspondence. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. p. 261.

- ^ "Movements of Marines". New-York Tribune. November 16, 1859. p. 6. Archived from the original on August 25, 2021. Retrieved April 2, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "News, &c". Oswego Daily Palladium (Oswego, New York). December 5, 1859. p. 6. Archived from the original on October 18, 2020. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- ^ "Old John Brown. The Story of the Famous Raid at Harpers Ferry. A foolhardy attempt. It Was the Result of Thirty Years of Planning—No One Believed It Would Succeed but Brown—What Influence It Had Upon the Civil War That So Soon Followed". Evening Star (Washington, D.C.). June 24, 1893. p. 7. Archived from the original on May 3, 2021. Retrieved May 3, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Brown's pikes pique interest". News Leader (Staunton, Virginia). June 15, 2009. p. 3. Archived from the original on August 25, 2021. Retrieved April 5, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Harpers Ferry Raid". pbs.org. Archived from the original on January 9, 2017. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f DeCaro Jr., Louis (2015). Freedom's Dawn. The Last Days of John Brown in Virginia. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781442236721.

- ^ Philips, G. M. (March 1, 1913). "A John Brown Story". The Outlook. p. 504.

- ^ James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (2003) p. 205

- ^ "Osborne P. Anderson". The Christian Recorder (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania). October 26, 1872. p. 4. Archived from the original on August 25, 2021. Retrieved August 25, 2021 – via accessiblearchives.com.

- ^ Pratte, Alf (October–December 1986). "'When my bees swarm..'". Negro History Bulletin. 49 (4): 13–16. JSTOR 44176900. Archived from the original on September 2, 2020. Retrieved September 14, 2021.

- ^ Sanborn, Franklin (July 1872). "John Brown and His Friends". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- ^ Laughlin-Schultz, Bonnie (2013). The Tie That Bound Us : The Women of John Brown's Family and the Legacy of Radical Abolitionism. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. p. 67. ISBN 9780801469442.

- ^ National Park Service History Series. John Brown's Raid (2009), pp. 22–30.

- ^ Allan Nevins, The Emergence of Lincoln: Prelude to Civil War, 1859–1861 (1950), vol. 4, pp. 72–73

- ^ "John Brown. A Reunion of His Surviving Associates. Recollections of the Battle of Black Jack—Bloody Scenes of Early Days in Kansas—Old Osawatomie's Last Visit—The Preliminaries to Harper's Ferry—Several Very Interesting Narratives". Topeka Daily Capital (Topeka, Kansas). October 24, 1882. p. 4. Archived from the original on August 25, 2021. Retrieved February 7, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ National Park Service History Series. John Brown's Raid (2009), p. 16

- ^ a b c d Oates, Stephen B. (1984). To Purge this Land with Blood: A Biography of John Brown (2nd ed.). Amherst, Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 0870234587. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

- ^ National Park Service. John Brown's Raid (2009), p. 16

- ^ Bennett, Lerone Jr. (May 1979). "A Historical Detective Story, Part II: Mystery of Mary Ellen Pleasant". Ebony. Vol. 34, no. 7. Johnson Publishing Company. pp. 71–72, 74, 76, 80, 82.

- ^ "The Warning to Secretary Floyd". National Era (Washington, D.C.). October 27, 1859. p. 172. Archived from the original on November 21, 2020. Retrieved November 14, 2020 – via accessiblearchives.com.

- ^ Richman, Irving B. (1897). John Brown among the Quakers, and other sketches. Des Moines, Iowa: Historical Department of Iowa. pp. 49–50.

- ^ Ted McGee (April 5, 1973), National Register of Historic Places Nomination: Beall-Air (PDF), National Park Service, archived from the original (PDF) on February 3, 2013

- ^ Frances D. Ruth (July 1984), National Register of Historic Places Nomination: Allstadt House and Ordinary (PDF), National Park Service, archived (PDF) from the original on June 4, 2011, retrieved March 16, 2009

- ^ a b Anderson, Osborne P. (1861). A voice from Harper's Ferry : a narrative of events at Harper's Ferry : with incidents prior and subsequent to its capture by Captain Brown and his men. Boston: The author.

- ^ Brands, H. W. (2020). The Zealot and the Emancipator: John Brown, Abraham Lincoln and the Struggle for American Freedom. New York: Doubleday. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-385-54400-9.

- ^ "John Brown's Raid". U.S. National Park Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved February 15, 2023.

- ^ Horton, James Oliver; Lois E. Horton (2006). Slavery and the Making of America. Oxford University Press USA. p. 162. ISBN 978-0195304510. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020. Retrieved November 26, 2015.

- ^ Shackel, Paul A. Memory in Black and White: Race, Commemoration, and the Post-Bellum Landscape. Walnut Creek, California: AltaMira Press, 2003, pp. 77-112.

- ^ Horwitz, Tony. Midnight Rising, p. 139.

- ^ a b United States Congress. Senate. Select Committee on the Harper's Ferry Invasion (June 15, 1860). "Testimony". In Mason, John Murray (ed.). Report on the Harper's Ferry Invasion. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- ^ "Change of time". Wheeling Daily Intelligencer (Wheeling, West Virginia). April 9, 1859. p. 3. Archived from the original on August 25, 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2020 – via newspaperarchive.com.

- ^ Oates, Stephen B. (Winter 1968). "John Brown's Bloody Pilgrimage". Southwest Review. 53 (1): 1–22, at p. 13. JSTOR 43467939.

- ^ a b c d e f Reynolds, David S. (2005). John Brown, Abolitionist. The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights. Vintage Books. ISBN 0375726152.

- ^ "Commander of the insurrectionists". Richmond Dispatch (Richmond, Virginia). October 20, 1859. p. 1. Archived from the original on August 29, 2020. Retrieved August 27, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "More on the Harpers Ferry Riot". The Athens Post (Athens, Tennessee). October 28, 1859. p. 1. Archived from the original on August 25, 2021. Retrieved September 14, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Fearful and exciting intelligence". New York Herald. October 18, 1859. p. 3. Archived from the original on August 29, 2020. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- ^ "The Insurrection at Harpers Ferry". Alexandria Gazette. October 19, 1859. p. 2. Archived from the original on August 29, 2020. Retrieved August 18, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Attempt to Establish Freedom. The attempt made". Anti-Slavery Bugle (Lisbon, Ohio). October 29, 1859. p. 1. Archived from the original on August 25, 2021. Retrieved November 25, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Harpers Ferry October Weather 2015 - AccuWeather Forecast for WV 25425". Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved August 26, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e A Citizen of Harpers Ferry (1859). Startling incidents & developments of Osowotomy Brown's insurrectory and treasonable movements at Harper's Ferry, Virginia, October 17th, 1859 : with a true and accurate account of the whole transaction. Baltimore. Archived from the original on July 10, 2021. Retrieved January 17, 2021 – via Adam Matthew (subscription required).

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Cook, John E. (November 11, 1859). Confession of John E. Cooke [sic], brother-in-law of Gov. A. P. Willard, of Indiana, and one of the participants in the Harper's Ferry invasion: published for the benefit of Samuel C. Young, a non-slaveholder, who is permanently disabled by a wound received in defence of Southern institutions. Charles Town, Virginia: D. Smith Eichelberger, publisher of the Independent Democrat. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Redpath, James (1860). The Public Life of Captain John Brown. Boston: Thayer and Eldridge.

- ^ "Further particulars of the attempted insurrection in Virginia". The Liberator. Boston, Massachusetts. October 28, 1859. p. 3. Archived from the original on August 25, 2021. Retrieved October 9, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Further from Harper's Ferry!". Wheeling Daily Intelligencer. October 20, 1869. p. 3. Archived from the original on August 29, 2020. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- ^ "The following dispatch has just been received from Frederick". Dawson's Fort Wayne Weekly Times (Fort Wayne, Indiana). October 15, 1859. p. 2. Archived from the original on August 29, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Lee, Robert E. (1902). "The John Brown Letters. Found in the Virginia State Library in 1901". Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. 10 (1). (Some reprints of this report, first published here, omit the appendices): 17–32, at pp. 18–25. JSTOR 4242480. Archived from the original on December 29, 2020. Retrieved November 28, 2020.

- ^ Daingerfield, John E.P. (June 1885). "John Brown at Harpers Ferry". The Century. pp. 265–267. Archived from the original on February 14, 2021. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- ^ a b Norris, J. E. (1890). History of the lower Shenandoah Valley counties of Frederick, Berkeley, Jefferson and Clarke, their early settlement and progress to the present time; geological features; a description of their historic and interesting localities; cities, towns and villages; portraits of some of the prominent men, and biographies of many of the representative citizens. Chicago: A. Warner & Co.

- ^ a b "Harpers Ferry Insurrection". National Era (Washington, D.C.). October 27, 1859 [October 18, 1859]. p. 4. Archived from the original on February 2, 2021. Retrieved December 1, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Monthly Record of Current Events. United States". Harper's. Vol. 20. December 1859. pp. 115–116.

- ^ Marquette, M. A. (March 23, 1916). "Story of John Brown's raid told by late M. A. Marquette". Portsmouth Daily Times (Portsmouth, Ohio). p. 10. Archived from the original on May 16, 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ De Witt, Robert M. (1859). The Life, Trial and Execution of Captain John Brown, Known as "Old Brown of Ossawatomie", with a full account of the attempted insurrection at Harper's Ferry, Virginia. Compiled from official and authentic sources. Inducting Cooke's Confession, and all the Incidents of the Execution. New York: Robert M. De Witt.

- ^ Strother, David H. (April 1965). Eby, Cecil D. (ed.). "The Last Hours of the John Brown Raid: The Narrative of David H. Strother". Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. 73 (2): 169–177 at p. 172 n. 11. JSTOR 4247105. Archived from the original on June 14, 2021. Retrieved May 19, 2021.

- ^ "Important from Harpers Ferry". Richmond Dispatch. October 21, 1859. Archived from the original on August 25, 2021. Retrieved September 13, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Korda, Michael (2014). Clouds of Glory : The Life and Legend of Robert E. Lee. An excerpt, "When Robert E. Lee Met John Brown and Saved the Union", was published in The Daily Beast. Harper. ISBN 978-0062116314.

- ^ a b "The insurrection at Harper's Ferry. —Antecedents of the originators. — Authentic details". Evening Star (Washington, D.C.). October 19, 1859. p. 2.

- ^ "Incidents of the second battle". Baltimore Sun. October 19, 1859. p. 1. Archived from the original on August 29, 2020. Retrieved August 26, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Where Abolitionist Leader Met His Waterloo". Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph. May 13, 1945. p. 47. Archived from the original on August 25, 2021. Retrieved February 22, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Greeley, Horace (1864). The American Conflict: A History: Part One. Kessinger. p. 292. ISBN 978-1417908288. Archived from the original on August 25, 2021. Retrieved October 23, 2020.

- ^ a b Keeler, Ralph (March 1874). "Owen Brown's Escape From Harper's Ferry". Atlantic Monthly. pp. 342–365. Archived from the original on August 25, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ "Effect of the News in Washington". Charleston Daily Courier (Charleston, South Carolina). October 22, 1859. p. 1. Archived from the original on August 25, 2021. Retrieved November 6, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Emory M. Thomas, Robert E. Lee: A Biography (1995) p. 180

- ^ Lee, Robert E. (1904). Recollections and letters of General Robert E. Lee. Robert E. Lee the author (1843–1914) is a son of Robert E. Lee the general (1807–1870). New York: Doubleday, Page. p. 22.

- ^ Korda, Michael (May 15, 2014). "When Robert e. Lee Met John Brown and Saved the Union". The Daily Beast.

- ^ "Owen Brown's Escape From Harper's Ferry". www.wvculture.org. Archived from the original on March 30, 2018. Retrieved June 28, 2021.

- ^ Simmons, William J., and Henry McNeal Turner. Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising. G. M. Rowell & Company, 1887. p. 160

- ^ a b Gath (May 2, 1883). "Reminiscences of Old John Brown, of Harper's Ferry. Striking Characteristics of the Man—The Object and the Possibilities of His Raid Into Virginia". The Cincinnati Enquirer. p. 1.

- ^ McGlone, Robert E. (1995). "John Brown, Henry Wise, and the Politics of Insanity". In Finkelman, Paul (ed.). His Soul Goes Marching On. Responses to John Brown and the Harpers Ferry Raid. Charlottesville, Virginia: University Press of Virginia. pp. 213–252, at p. 235. ISBN 0813915368.

- ^ Wyatt-Brown, Bertram (1995). "'A Volcano Beneath a Mountain of Snow': John Brown and the problem of Interpretation". In Finkelman, Paul (ed.). His Soul Goes Marching On. Responses to John Brown and the Harpers Ferry Raid. Charlottesville, Virginia: University Press of Virginia. pp. 10–38, at p. 25. ISBN 0813915368.

- ^ Lubet, Steven (June 1, 2013). "Execution in Virginia, 1859: The Trials of Green and Copeland". North Carolina Law Review. 91 (5): 1785–1815. Archived from the original on April 30, 2019. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- ^ Galbreath, C. B. "Vallandingham and John Brown". Ohio History Journal: 266–271. Archived from the original on June 2, 2021. Retrieved November 19, 2020.

- ^ DeCaro Jr., Louis A. (2002). "Fire from the Midst of You": A Religious Life of John Brown'. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 081471921X.

- ^ "A Long Conversation with Brown". The National Era (Washington, D.C.). October 27, 1859. p. 3. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved October 27, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Thoreau, Henry D. (November 5, 1859). "Captain John Brown of Ossawatomie". New York Herald. p. 4. Archived from the original on August 25, 2021. Retrieved February 3, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Letter to the editor of the Cincinnati Enquirer". Daily Empire (Dayton, Ohio). October 25, 1859. p. 1. Archived from the original on August 25, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Strother, D. H. (April 1965). Ely, Cecil D. (ed.). "The Last Hours of the John Brown Raid: The Narrative of David H. Strother". Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. 73 (2): 169–177. JSTOR 4247105. Archived from the original on June 14, 2021. Retrieved May 19, 2021.

- ^ "Effect of the news in Washington". The Daily Exchange (Baltimore, Maryland). October 19, 1859. p. 1. Archived from the original on August 29, 2020. Retrieved August 18, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Strother, David (October 21, 1859). "Military orders from Governor Wise". New York Herald. Signed "Our Special Correspondent". p. 1, column 3. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved September 12, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Hunter, Andrew (1897). "John Brown's Raid". Southern History Association. 1 (3): 165–195.

- ^ a b Sanborn, Franklin B; Brown, John (1885). The Life and Letters of John Brown, Liberator of Kansas, and Martyr of Virginia. Boston: Roberts Brothers.

- ^ "Gov. Wise's Return from Harper's Ferry—His Speech in Richmond". New York Daily Herald. October 25, 1859. p. 4. Archived from the original on October 30, 2020. Retrieved October 27, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Speech of Governor Wise at Richmond". New York Daily Herald. October 26, 1859. p. 1. Archived from the original on October 30, 2020. Retrieved October 27, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Gov Wise's Speech at Richmond on the Subject of the Harper's Ferry Rebellion". Alexandria Gazette (Alexandria, Virginia). October 27, 1859. p. 2. Archived from the original on August 25, 2021. Retrieved October 27, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Vallandingham, Clement (November 11, 1859). "Letter to unidentified recipient". The Liberator. Boston, Massachusetts. p. 1. Archived from the original on April 13, 2021. Retrieved May 11, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c [Strother, David (October 21, 1859). "The Harper's Ferry Outbreak. Verbatim Report of the Questioning of Old Brown by Senator Mason, Congressman Vallandigham, and Others. He Refuses to Disclose the Names of his Abettors, but Confesses to Interviews with Joshua R. Giddings, and Endorses Gerrit Smith's Letter. He Declares that he Received his Wounds After Surrendering. His Statement to the Herald Reporter. The Slavery Question Must Come up for Settlement Sooner than the Southern People Calculate on. The Property of Slaveholders to have been Confiscated. Military Orders from Gov. Wise. He is Mortified at the Disgrace Brought on the State—Brown's Magazine. Letter from Gerrit Smith to Capt. Brown. The Abolitionist and Black Republican Press on the Outbreak, &c., &c., A&c". New York Daily Herald. Signed "Our Special Reporter". p. 1. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved September 12, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Latest by telegraph. Our special despatches". Daily Exchange (Baltimore, Maryland). October 20, 1859 [October 19, 1859]. p. 1. Archived from the original on August 25, 2021. Retrieved March 19, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Skeleton of a provisional constitution and ordinances of the people of the U.S., and related letter to his family. Chatham, Ontario: WorldCat. 1858. OCLC 702150296. Archived from the original on August 25, 2021. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- ^ "Affairs at Charlestown. Journey of the Richmond Troops to Charlestown—The Meeting in the Town—New Developments in the Rescue of the Murderers—The People of Charlestown". Richmond Dispatch (Richmond, Virginia). November 23, 1859. p. 1. Archived from the original on July 21, 2021. Retrieved February 26, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Brown in jail". New-York Tribune. November 5, 1859. p. 5. Archived from the original on August 25, 2021. Retrieved November 15, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Brown, John (November 8, 1859), Letter to his wife and children, archived from the original on December 9, 2020, retrieved December 9, 2020

- ^ James M. McPherson. Battle Cry of Freedom. New York: Oxford University Press (1988), pp. 207–208.

- ^ Mitchell, Betty L., "Massachusetts Reacts To John Brown's Raid", Civil War History, Vol. 19, No. 1, March 1973, pp. 65-79 (quotations at p. 66).

- ^ Soon after, Garrison changed his view, expressing a preference for slaves "breaking the head of the tyrant with their chains". Mitchell, Betty L., "Massachusetts Reacts To John Brown's Raid", p. 75.

- ^ Norton Anthology of American Literature, Volume B. p. 2057.

- ^ James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (2003), p. 210

- ^ a b "The Harper's Ferry Invasion as Party Capital". Richmond Enquirer (Richmond, Virginia). October 25, 1859. p. 1.

- ^ Blaser, Kent, "North Carolina and John Brown's Raid", Civil War History, Vol. 24, No. 3, September 1978, pp. 197-212 (quotations on pp. 199, 200).

- ^ Burge, Daniel J. (Summer 2023). "John Brown, Filibuster: Republicans, Harpers Ferry, and the Use of Violence, 1855–1860". Journal of the Early Republic. 43 (2): 245–268. doi:10.1353/jer.2023.a897985. ISSN 1553-0620. Retrieved June 30, 2024 – via Project MUSE.

- ^ "The Hanging". PBS.