The crucifixion of Jesus was the death of Jesus by being nailed to a cross.[note 1] It occurred in 1st-century Judaea, most likely in AD 30 or AD 33. It is described in the four canonical gospels, referred to in the New Testament epistles, and later attested to by other ancient sources. Scholars nearly universally accept the historicity of Jesus's crucifixion,[1] although there is no consensus on the details.[2][3][4]

| |

| Date | AD 30/33 |

|---|---|

| Location | Jerusalem, Judaea, Roman Empire |

| Type | Execution by crucifixion |

| Cause | Condemnation before Pilate's court |

| Participants | Roman army (executioners) |

| Outcome |

|

| Deaths | Jesus |

According to the canonical gospels, Jesus was arrested and tried by the Sanhedrin, and then sentenced by Pontus Pilate, after a crowd of Judeans chose for Jesus to be executed rather than Barabbas. [5], to be scourged, and finally crucified by the Romans.[6][7][8] The Gospel of John portrays his death as a sacrifice for sin.

Jesus was stripped of his clothing and offered vinegar mixed with myrrh or gall (likely posca)[9] to drink after saying "I am thirsty". At Golgotha, he was then hung between two convicted thieves and, according to the Gospel of Mark, was crucified at the 3rd hour (9 a.m.), and died by the 9th hour of the day (at around 3:00 p.m.). During this time, the soldiers affixed a sign to the top of the cross stating "Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews" which, according to the Gospel of John (John 19:20), was written in three languages (Hebrew, Latin, and Greek). They then divided his garments among themselves and cast lots for his seamless robe, according to the Gospel of John. The Gospel of John also states that, after Jesus's death, one soldier (named in extra-Biblical tradition as Longinus) pierced his side with a spear to be certain that he had died, then blood and water gushed from the wound. The Bible describes seven statements that Jesus made while he was on the cross, as well as several supernatural events that occurred.

Collectively referred to as the Passion, Jesus's suffering and redemptive death by crucifixion are the central aspects of Christian theology concerning the doctrines of salvation and atonement.

New Testament narratives

editPaul is the earliest surviving source (outside of the Gospels) to document Jesus's crucifixion.[10] Scholars have used Paul's chronology as evidence for the date of the crucifixion.[11] However, the earliest detailed accounts of the death of Jesus are contained in the four canonical gospels.[12] In the synoptic gospels, Jesus predicts his death in three separate places.[13] All four Gospels conclude with an extended narrative of Jesus's arrest, initial trial at the Sanhedrin and final trial at Pilate's court, where Jesus is flogged, condemned to death, is led to the place of crucifixion initially carrying his cross before Roman soldiers induce Simon of Cyrene to carry it, and then Jesus is crucified, entombed, and resurrected from the dead. In each Gospel these five events in the life of Jesus are treated with more intense detail than any other portion of that Gospel's narrative. Scholars note that the reader receives an almost hour-by-hour account of what is happening.[14]: p.91

After arriving at Golgotha, Jesus was offered wine mixed with myrrh or gall to drink. Both the Gospel of Mark and the Gospel of Matthew record that he refused this. He was then crucified and hanged between two convicts. According to some translations of the original Greek, the convicts may have been bandits or Jewish rebels.[15] According to the Gospel of Mark, he endured the torment of crucifixion from the third hour (between approximately 9 a.m. and noon),[16] until his death at the ninth hour, corresponding to about 3 p.m.[17] The soldiers affixed a sign above his head stating "Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews" which, according to the Gospel of John, was in three languages (Hebrew, Latin, and Greek), and then divided his garments and cast lots for his seamless robe. According to the Gospel of John, the Roman soldiers did not break Jesus's legs, as they did to the two crucified convicts (breaking the legs hastened the onset of death), as Jesus was dead already. Each gospel has its own account of Jesus's last words, seven statements altogether.[18] In the Synoptic Gospels, various supernatural events accompany the crucifixion, including darkness, an earthquake, the tearing of the sanctuary's veil and the resurrection of saints (in the Gospel of Matthew).[19] Following Jesus's death, his body was removed from the cross by Joseph of Arimathea and buried in a rock-hewn tomb, with Nicodemus assisting.

The three Synoptic gospels also describe Simon of Cyrene bearing the cross,[20] a crowd of people mocking Jesus[21] along with the other two crucified men,[22] darkness from the 6th to the 9th hour,[23] and the temple veil being torn from top to bottom.[24] The Synoptic Gospels also mention several witnesses, including a centurion,[25] and several women who watched from a distance,[26] two of whom were present during the burial.[27]

The Gospel of Luke is the only gospel to omit the detail of the sour wine mix that was offered to Jesus on a reed,[28] while only Mark and John describe Joseph actually taking the body down off the cross.[29]

There are several details that are only mentioned in a single gospel account. For instance, only the Gospel of Matthew mentions an earthquake, resurrected saints who went to the city and that Roman soldiers were assigned to guard the tomb,[30] while Mark is the only one to state the time of the crucifixion (the third hour, or 9 a.m. – although it was probably as late as noon)[31] and the centurion's report of Jesus's death.[32] The Gospel of Luke's unique contributions to the narrative include Jesus's words to the women who were mourning, one criminal's rebuke of the other, the reaction of the multitudes who left "beating their breasts", and the women preparing spices and ointments before resting on the Sabbath.[33] John is also the only one to refer to the request that the legs be broken and the soldier's subsequent piercing of Jesus's side (as fulfillment of Old Testament prophecy), as well as that Nicodemus assisted Joseph with burial.[34]

According to the First Epistle to the Corinthians (1 Corinthians 15:4), Jesus was raised from the dead ("on the third day" counting the day of crucifixion as the first) and according to the canonical gospels, appeared to his disciples on different occasions before ascending to heaven.[35] The account given in Acts of the Apostles says that Jesus remained with the apostles for 40 days, whereas the account in the Gospel of Luke makes no clear distinction between the events of Easter Sunday and the Ascension.[36][37] Most biblical scholars agree that the author of Luke also wrote the Acts of the Apostles as a follow-up volume to the Gospel of Luke account, and the two works must be considered as a whole.[38]

In Mark, Jesus is crucified along with two rebels, and the sun goes dark or is obscured for three hours.[39] Jesus calls out to God, then gives a shout and dies.[39] The curtain of the Temple is torn in two.[39] Matthew follows Mark, but mentions an earthquake and the resurrection of saints.[40] Luke also follows Mark, although he describes the rebels as common criminals, one of whom defends Jesus, who in turn promises that he (Jesus) and the criminal will be together in paradise.[41] Luke portrays Jesus as impassive in the face of his crucifixion.[42] John includes several of the same elements as those found in Mark, though they are treated differently.[43]

Textual comparison

editThe comparison below is based on the New International Version.

| Matthew | Mark | Luke | John | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Way of the Cross | Matthew 27:32–33

|

Mark 15:21–22

|

Luke 23:26–32

|

John 19:17

|

| Crucifixion | Matthew 27:34–36

|

Mark 15:23–25

|

Luke 23:33–34

|

John 19:18, 23–24

|

| Mocking | Matthew 27:37–44

|

Mark 15:26–32

|

Luke 23:35–43

|

John 19:19–22, 25–27

|

| Death | Matthew 27:45–56

|

Mark 15:33–41

|

Luke 23:44–49

|

John 19:28–37

|

Other accounts and references

editMara Bar-Serapion

editAn early non-Christian reference to the crucifixion of Jesus is likely to be Mara Bar-Serapion's letter to his son, written some time after AD 73 but before the 3rd century AD.[47][48][49] The letter includes no Christian themes and the author is presumed to be neither Jewish nor Christian.[47][48][50] The letter refers to the retributions that followed the unjust treatment of three wise men: Socrates, Pythagoras, and "the wise king" of the Jews.[47][49] Some scholars see little doubt that the reference to the execution of the "king of the Jews" is about the crucifixion of Jesus, while others place less value in the letter, given the ambiguity in the reference.[50][51]

Josephus

editIn the Antiquities of the Jews (written about AD 93) Jewish historian Josephus stated (Ant 18.3) that Jesus was crucified by Pilate, writing that:[52]

Now there was about this time Jesus, a wise man, ... He drew over to him both many of the Jews and many of the Gentiles ... And when Pilate, at the suggestion of the principal men amongst us, had condemned him to the cross ...

Most modern scholars agree that while this Josephus passage (called the Testimonium Flavianum) includes some later interpolations, it originally consisted of an authentic nucleus with a reference to the execution of Jesus by Pilate.[6][7] James Dunn states that there is "broad consensus" among scholars regarding the nature of an authentic reference to the crucifixion of Jesus in the Testimonium.[53]

Tacitus

editEarly in the second century another reference to the crucifixion of Jesus was made by Tacitus, generally considered one of the greatest Roman historians.[54][55] Writing in The Annals (c. AD 116), Tacitus described the persecution of Christians by Nero and stated (Annals 15.44) that Pilate ordered the execution of Jesus:[52][56]

Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians by the populace. Christus, from whom the name had its origin, suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus.

Scholars generally consider the Tacitus reference to the execution of Jesus by Pilate to be genuine, and of historical value as an independent Roman source.[54][57][58][59][60][61] Eddy and Boyd state that it is now "firmly established" that Tacitus provides a non-Christian confirmation of the crucifixion of Jesus.[62]

Talmud

editAnother possible reference to the crucifixion ("hanging", cf. Luke 23:39; Galatians 3:13) is found in the Babylonian Talmud:

On the eve of the Passover Yeshu was hanged. For forty days before the execution took place, a herald went forth and cried, "He is going forth to be stoned because he has practised sorcery and enticed Israel to apostasy. Anyone who can say anything in his favour, let him come forward and plead on his behalf." But since nothing was brought forward in his favour he was hanged on the eve of the Passover.

— Sanhedrin 43a, Babylonian Talmud (Soncino Edition)

Although the question of the equivalence of the identities of Yeshu and Jesus has at times been debated, many historians agree that the above 2nd-century passage is likely to be about Jesus, Peter Schäfer stating that there can be no doubt that this narrative of the execution in the Talmud refers to Jesus of Nazareth.[63] Robert Van Voorst states that the Sanhedrin 43a reference to Jesus can be confirmed not only from the reference itself, but from the context that surrounds it.[64] Sanhedrin 43a relates that Yeshu had been condemned to death by the royal government of Judaea – this lineage was stripped of all legal authority upon Herod the Great's ascension to the throne in 37 BC, meaning the execution had to have taken place close to 40 years before Jesus was even born.[65][66]

Islam

editMuslims maintain that Jesus was not crucified and that those who thought they had killed him had mistakenly killed Judas Iscariot, Simon of Cyrene, or someone else in his place.[67] They hold this belief based on various interpretations of Quran 4:157–158, which states: "they killed him not, nor crucified him, but so it was made to appear to them [or it appeared so unto them], ... Nay, Allah raised him up unto Himself".[67]

Gnosticism

editSome early Christian Gnostic sects, believing Jesus did not have a physical substance, denied that he was crucified.[68][69] In response, Ignatius of Antioch insisted that Jesus was truly born and was truly crucified and wrote that those who held that Jesus only seemed to suffer only seemed to be Christians.[70][71]

Historicity

editIn scholarship on the historical Jesus, the baptism of Jesus and his crucifixion are considered to be the two most certain historical facts about Jesus.[72][73][4][74][75][note 2] Various criteria are used to determine the historicity of the elements of the New Testamentical narratives, and help to establish the crucifixion of Jesus as a historical event.[74] The criterion of embarrassment argues that Christians would not have invented the painful death of their leader.[74] The criterion of multiple attestation is the confirmation by more than one source,[76] including multiple non-Christian sources,[note 3] and the criterion of coherence argues that it fits with other historical elements.[76]

Although scholars agree on the historicity of the crucifixion, they differ on the reason and context for it.[77] For example, both E. P. Sanders and Paula Fredriksen support the historicity of the crucifixion, but contend that Jesus did not foretell his own crucifixion and that his prediction of the crucifixion is a "church creation".[78]: 126 On the other hand, Michael Patrick Barber argues that the Historical Jesus predicted his violent death.[79] Tucker Ferda argues that the Historical Jesus did believe he might die.[80] Geza Vermes also views the crucifixion as a historical event, but provides his own explanation and background for it.[78] Bart Ehrman states that Jesus portrayed himself as the header of the future Kingdom and that a number of criteria- the criterion of multiple attestation and criterion of dissimilarity - establishes the crucifixion of Jesus as an enemy of state.[81]

Although almost all ancient sources relating to crucifixion are literary, in 1968, an archeological discovery just northeast of Jerusalem uncovered the body of a crucified man dated to the 1st century, which provided good confirmatory evidence that crucifixions occurred during the Roman period roughly according to the manner in which the crucifixion of Jesus is described in the gospels.[82] The crucified man was identified as Yehohanan ben Hagkol and probably died about AD 70, around the time of the Jewish revolt against Rome. The analyses at the Hadassah Medical School estimated that he died in his late 20s.[83][84] Another relevant archaeological find, which also dates to the 1st century AD, is an unidentified heel bone with a spike discovered in a Jerusalem gravesite, now held by the Israel Antiquities Authority and displayed in the Israel Museum.[85]

Details

editChronology

editThere is no consensus regarding the exact date of the crucifixion of Jesus, although it is generally agreed by biblical scholars that it was on a Friday on or near Passover (Nisan 14), during the governorship of Pontius Pilate (who ruled AD 26–36).[86] Various approaches have been used to estimate the year of the crucifixion, including the canonical Gospels, the chronology of the life of Paul, as well as different astronomical models. Scholars have provided estimates in the range AD 30–33,[87][88][89][11] with Rainer Riesner stating that "the fourteenth of Nisan (7 April) of the year 30 AD is, apparently in the opinion of the majority of contemporary scholars as well, far and away the most likely date of the crucifixion of Jesus."[90] Another preferred date among scholars is Friday, 3 April, AD 33.[91][92]

The consensus of scholarship is that the New Testament accounts represent a crucifixion occurring on a Friday, but a Thursday or Wednesday crucifixion have also been proposed.[93] Some scholars explain a Thursday crucifixion based on a "double sabbath" caused by an extra Passover sabbath falling on Thursday dusk to Friday afternoon, ahead of the normal weekly Sabbath.[94] Some have argued that Jesus was crucified on Wednesday, not Friday, on the grounds of the mention of "three days and three nights" in Matthew 12:40 before his resurrection, celebrated on Sunday. Others have countered by saying that this ignores the Jewish idiom by which a "day and night" may refer to any part of a 24-hour period, that the expression in Matthew is idiomatic, not a statement that Jesus was 72 hours in the tomb, and that the many references to a resurrection on the third day do not require three literal nights.[95]

In Mark 15:25 crucifixion takes place at the third hour (9 a.m.) and Jesus's death at the ninth hour (3 p.m.).[96] In John 19:14 Jesus is still before Pilate at the sixth hour.[97] Scholars have presented a number of arguments to deal with the issue, some suggesting a reconciliation, e.g., based on the use of Roman timekeeping in John, since Roman timekeeping began at midnight and this would mean being before Pilate at the 6th hour was 6 a.m., yet others have rejected the arguments.[97][98][99] Several scholars have argued that the modern precision of marking the time of day should not be read back into the gospel accounts, written at a time when no standardization of timepieces, or exact recording of hours and minutes was available, and time was often approximated to the closest three-hour period.[97][100][101]

Path

editThe three Synoptic Gospels refer to a man called Simon of Cyrene whom the Roman soldiers order to carry the cross after Jesus initially carries it but then collapses,[102] while the Gospel of John just says that Jesus "bears" his own cross.[103]

Luke's gospel also describes an interaction between Jesus and the women among the crowd of mourners following him, quoting Jesus as saying "Daughters of Jerusalem, do not weep for me, but weep for yourselves and for your children. For behold, the days are coming when they will say, 'Blessed are the barren and the wombs that never bore and the breasts that never nursed!' Then they will begin to say to the mountains, 'Fall on us,' and to the hills, 'Cover us.' For if they do these things when the wood is green, what will happen when it is dry?"[104]

The Gospel of Luke has Jesus address these women as "daughters of Jerusalem", thus distinguishing them from the women whom the same gospel describes as "the women who had followed him from Galilee" and who were present at his crucifixion.[105]

Traditionally, the path that Jesus took is called Via Dolorosa (Latin for "Way of Grief" or "Way of Suffering") and is a street in the Old City of Jerusalem. It is marked by nine of the fourteen Stations of the Cross. It passes the Ecce Homo Church and the last five stations are inside the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

There is no reference to a woman named Veronica in the Gospels,[106] but sources such as Acta Sanctorum describe her as a pious woman of Jerusalem who, moved with pity as Jesus carried his cross to Golgotha, gave him her veil that he might wipe his forehead.[107][108][109][110]

Location

editThe precise location of the crucifixion remains a matter of conjecture, but the biblical accounts indicate that it was outside the city walls of Jerusalem,[111] accessible to passers-by[112] and observable from some distance away.[113] Eusebius identified its location only as being north of Mount Zion,[114] which is consistent with the two most popularly suggested sites of modern times.

Calvary as an English name for the place is derived from the Latin word for skull (calvaria), which is used in the Vulgate translation of "place of a skull", the explanation given in all four Gospels of the Aramaic word Gûlgaltâ (transliterated into the Greek as Γολγοθᾶ (Golgotha)), which was the name of the place where Jesus was crucified.[115] The text does not indicate why it was so designated, but several theories have been put forward. One is that as a place of public execution, Calvary may have been strewn with the skulls of abandoned victims (which would be contrary to Jewish burial traditions, but not Roman). Another is that Calvary is named after a nearby cemetery (which is consistent with both of the proposed modern sites). A third is that the name was derived from the physical contour, which would be more consistent with the singular use of the word, i.e., the place of "a skull". While often referred to as "Mount Calvary", it was more likely a small hill or rocky knoll.[116]

The traditional site, inside what is now occupied by the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in the Christian Quarter of the Old City, has been attested since the 4th century. A second site (commonly referred to as Gordon's Calvary[117]), located further north of the Old City near a place popularly called the Garden Tomb, has been promoted since the 19th century.

People present

editThe Gospels describe various women at the crucifixion, some of whom are named. According to Mark, many women were present, among them Mary Magdalene, Mary, mother of James and Mary of Clopas,[118] commonly known as "the Three Marys". The Gospel of Matthew also mentions several women being present, among them Mary Magdalene, Mary, mother of James and the mother of Zebedee's children.[119] Although a group of women is mentioned in Luke, neither is named.[120] The Gospel of John speaks of women present, among them the mother of Jesus, Mary Magdalene and Mary of Clopas.[121]

Aside from these women, the three Synoptic Gospels speak of the presence of others: "the chief priests, with the scribes and elders",[122] two crucified criminals, to Jesus's right and left,[123] "the soldiers",[124] "the centurion and those who were with him, keeping watch over Jesus",[125] passers-by,[126] "bystanders",[127] "the crowds that had assembled for this spectacle",[128] and "his acquaintances".[120] The two criminals are described as λῃσταί (variously translated as robbers, rebels or thieves) and further discussed in the Gospel of Luke as the penitent thief and the impenitent thief.[129]

The Gospel of John mentions the soldiers[130] and "the disciple whom Jesus loved", who is with the women.[131]

The Gospels also tell of the arrival, after the death of Jesus, of Joseph of Arimathea (in the four Gospels)[132] and of Nicodemus (only in John).[133]

Method and manner

editWhereas most Christians believe the gibbet on which Jesus was executed was the traditional two-beamed cross, the Jehovah's Witnesses hold the view that a single upright stake was used. The Greek and Latin words used in the earliest Christian writings are ambiguous. The Koine Greek terms used in the New Testament are stauros (σταυρός) and xylon (ξύλον). The latter means wood (a live tree, timber or an object constructed of wood); in earlier forms of Greek, the former term meant an upright stake or pole, but in Koine Greek it was used also to mean a cross.[134] The Latin word crux was also applied to objects other than a cross.[135]

Early Christian writers who speak of the shape of the particular gibbet on which Jesus died invariably describe it as having a cross-beam. For instance, the Epistle of Barnabas, which was certainly earlier than 135,[136] and may have been of the 1st century AD,[137] the time when the gospel accounts of the death of Jesus were written, likened it to the letter T (the Greek letter tau, which had the numeric value of 300),[138] and to the position assumed by Moses in Exodus 17:11–12.[139] Justin Martyr (100–165) explicitly says the cross of Christ was of two-beam shape: "That lamb which was commanded to be wholly roasted was a symbol of the suffering of the cross which Christ would undergo. For the lamb, which is roasted, is roasted and dressed up in the form of the cross. For one spit is transfixed right through from the lower parts up to the head, and one across the back, to which are attached the legs of the lamb."[140] Irenaeus, who died around the end of the 2nd century, speaks of the cross as having "five extremities, two in length, two in breadth, and one in the middle, on which [last] the person rests who is fixed by the nails."[141]

The assumption of the use of a two-beamed cross does not determine the number of nails used in the crucifixion and some theories suggest three nails while others suggest four nails.[142] Throughout history, larger numbers of nails have been hypothesized, at times as high as 14 nails.[143] These variations are also present in the artistic depictions of the crucifixion.[144] In Western Christianity, before the Renaissance usually four nails would be depicted, with the feet side by side. After the Renaissance most depictions use three nails, with one foot placed on the other.[144] Nails are almost always depicted in art, although Romans sometimes just tied the victims to the cross.[144] The tradition also carries to Christian emblems, e.g. the Jesuits use three nails under the IHS monogram and a cross to symbolize the crucifixion.[145]

The placing of the nails in the hands, or the wrists is also uncertain. Some theories suggest that the Greek word cheir (χείρ) for hand includes the wrist and that the Romans were generally trained to place nails through Destot's space (between the capitate and lunate bones) without fracturing any bones.[146] Another theory suggests that the Greek word for hand also includes the forearm and that the nails were placed near the radius and ulna of the forearm.[147] Ropes may have also been used to fasten the hands in addition to the use of nails.[148]

Another issue of debate has been the use of a hypopodium as a standing platform to support the feet, given that the hands may not have been able to support the weight. In the 17th century Rasmus Bartholin considered a number of analytical scenarios of that topic.[143] In the 20th century, forensic pathologist Frederick Zugibe performed a number of crucifixion experiments by using ropes to hang human subjects at various angles and hand positions.[147] His experiments support an angled suspension, and a two-beamed cross, and perhaps some form of foot support, given that in an Aufbinden form of suspension from a straight stake (as used by the Nazis in the Dachau concentration camp during World War II), death comes rather quickly.[149]

Words of Jesus spoken from the cross

editThe Gospels describe various last words that Jesus said while on the cross,[150] as follows:

Mark / Matthew

edit- E′li, E′li, la′ma sa‧bach‧tha′ni? [151] (Aramaic for "My God, My God, why have you forsaken me?"). Aramaic linguist Steve Caruso said Jesus most likely spoke Galilean Aramaic,[152] which would render the pronunciation of these words: əlahí əlahí ləmáh šəvaqtáni.[153]

The only words of Jesus on the cross mentioned in the Mark and Matthew accounts, this is a quotation of Psalm 22. Since other verses of the same Psalm are cited in the crucifixion accounts, some commentators consider it a literary and theological creation. Geza Vermes noted the verse is cited in Aramaic rather than the usual Hebrew, and that by the time of Jesus, this phrase had become a proverbial saying in common usage.[154] Compared to the accounts in the other Gospels, which he describes as "theologically correct and reassuring", he considers this phrase "unexpected, disquieting and in consequence more probable".[155] He describes it as bearing "all the appearances of a genuine cry".[156] Raymond Brown likewise comments that he finds "no persuasive argument against attributing to the Jesus of Mark/Matt the literal sentiment of feeling forsaken expressed in the Psalm quote".[157]

Luke

edit- "Father, forgive them; for they do not know what they are doing."[158] [Some early manuscripts do not have this]

- "Truly I tell you, today you will be with me in Paradise."[159]

- "Father, into your hands I commend my spirit."[160]

The Gospel of Luke does not include the aforementioned exclamation of Jesus mentioned in the Matthew and Mark accounts.[161]

John

editThe words of Jesus on the cross, especially his last words, have been the subject of a wide range of Christian teachings and sermons, and a number of authors have written books specifically devoted to the last sayings of Christ.[165][166][167][168][169][170]

Reported extraordinary occurrences

editThe synoptics report various miraculous events during the crucifixion.[171][172] Mark mentions a period of darkness in the daytime during Jesus's crucifixion, and the Temple veil being torn in two when Jesus dies.[39] Luke follows Mark;[41] as does Matthew, additionally mentioning an earthquake and the resurrection of dead saints.[40] No mention of any of these appears in John.[173]

Darkness

editIn the synoptic narrative, while Jesus is hanging on the cross, the sky over Judaea (or the whole world) is "darkened for three hours," from the sixth to the ninth hour (noon to mid-afternoon). There is no reference to darkness in the Gospel of John account, in which the crucifixion does not take place until after noon.[174]

Some ancient Christian writers considered the possibility that pagan commentators may have mentioned this event and mistook it for a solar eclipse, pointing out that an eclipse could not occur during the Passover, which takes place during the full moon when the moon is opposite the sun rather than in front of it. Christian traveler and historian Sextus Julius Africanus and Christian theologian Origen refer to Greek historian Phlegon, who lived in the 2nd century AD, as having written "with regard to the eclipse in the time of Tiberius Caesar, in whose reign Jesus appears to have been crucified, and the great earthquakes which then took place".[175]

Sextus Julius Africanus further refers to the writings of historian Thallus: "This darkness Thallus, in the third book of his History, calls, as appears to me without reason, an eclipse of the sun. For the Hebrews celebrate the Passover on the 14th day according to the moon, and the passion of our Saviour falls on the day before the Passover; but an eclipse of the sun takes place only when the moon comes under the sun."[176] Christian apologist Tertullian believed the event was documented in the Roman archives.[177]

Colin Humphreys and Graeme Waddington of Oxford University considered the possibility that a lunar, rather than solar, eclipse might have taken place.[178][179] They concluded that such an eclipse was visible in Jerusalem on the date of April 3, AD 33, that its peak was at 5:15 pm Jerusalem time, but that it was visible after sundown (the beginning of the Sabbath and of Passover) for half an hour. Some of the oldest manuscripts of Luke say "the sun was eclipsed" (23:45) at the time of the crucifixion. The authors suggest that this may be due to a scribe changing the word "moon" to "sun" to explain the darkness, or else that the word "eclipsed" just meant darkened or hidden, as in a passage of the Sibylline Oracles. Historian David Henige dismisses this explanation[which?] as "indefensible".[180] More objectively, astronomer Bradley Schaefer later found that the lunar eclipse would not have been visible at moonrise due to the brightness of the sky, and the umbra (the part that would be red) would not have been visible before it disappeared a few minutes later.[181][182]

In an edition of the BBC Radio 4 programmed In Our Time entitled Eclipses, Frank Close, Emeritus Professor of Physics at the University of Oxford, stated that certain historical sources say that on the night of the Crucifixion "the moon had risen blood red," which indicates a lunar eclipse. He went on to confirm that as Passover takes place on the full moon calculating back shows that a lunar eclipse did in fact take place on the night of Passover on Friday, 3 April 33 AD which would have been visible in the area of modern Israel, ancient Judaea, just after sunset.[183]

Modern biblical scholarship treats the account in the synoptic gospels as a literary creation by the author of the Mark Gospel, amended in the Luke and Matthew accounts, intended to heighten the importance of what they saw as a theologically significant event, and not intended to be taken literally.[184] This image of darkness over the land would have been understood by ancient readers, a typical element in the description of the death of kings and other major figures by writers such as Philo, Dio Cassius, Virgil, Plutarch and Josephus.[185] Géza Vermes describes the darkness account as typical of "Jewish eschatological imagery of the day of the Lord", and says that those interpreting it as a datable eclipse are "barking up the wrong tree".[186]

Temple veil, earthquake and resurrection of dead saints

editThe synoptic gospels state that the veil of the temple was torn from top to bottom.

The Gospel of Matthew mentions an account of earthquakes, rocks splitting, and the opening of the graves of dead saints, and describes how these resurrected saints went into the holy city and appeared to many people.[187]

In the Mark and Matthew accounts, the centurion in charge comments on the events: "Truly this man was the Son of God!"[188] or "Truly this was the Son of God!".[189] The Gospel of Luke quotes him as saying, "Certainly this man was innocent!"[190][191]

The historian Sextus Julius Africanus in the early third century wrote, describing the day of the crucifixion, "A most terrible darkness fell over all the world, the rocks were torn apart by an earthquake, and many places both in Judaea and the rest of the world were thrown down. In the third book of his Histories, Thallos dismisses this darkness as a solar eclipse. ..."[192]

A widespread earthquake of magnitude at least 5.5 has been confirmed to have taken place in the region between AD 26 and 36. This earthquake was dated by counting varves (annual layers of sediment) between the disruptions in a core of sediment from En Gedi caused by it and by an earlier known quake in 31 BC.[193] The authors concluded that either this was the earthquake in Matthew and it occurred more or less as reported, or else Matthew "borrowed" this earthquake which actually occurred at another time or simply inserted an "allegorical fiction".

Medical aspects

editA number of theories to explain the circumstances of the death of Jesus on the cross have been proposed by physicians and Biblical scholars. In 2006, Matthew W. Maslen and Piers D. Mitchell reviewed over 40 publications on the subject with theories ranging from cardiac rupture to pulmonary embolism.[194]

In 1847, based on the reference in the Gospel of John (John 19:34) to blood and water coming out when Jesus's side was pierced with a spear, physician William Stroud proposed the ruptured heart theory of the cause of Christ's death which influenced a number of other people.[195][196]

The cardiovascular collapse theory is a prevalent modern explanation and suggests that Jesus died of profound shock. According to this theory, the scourging, the beatings, and the fixing to the cross left Jesus dehydrated, weak, and critically ill and this led to cardiovascular collapse.[197]

Writing in the Journal of the American Medical Association, physician William Edwards and his colleagues supported the combined cardiovascular collapse (via hypovolemic shock) and exhaustion asphyxia theories, assuming that the flow of water from the side of Jesus described in the Gospel of John[198] was pericardial fluid.[199]

In his book The Crucifixion of Jesus, physician and forensic pathologist Frederick Zugibe studied the likely circumstances of the death of Jesus in great detail.[200][201] Zugibe carried out a number of experiments over several years to test his theories while he was a medical examiner.[202] These studies included experiments in which volunteers with specific weights were hanging at specific angles and the amount of pull on each hand was measured, in cases where the feet were also secured or not. In these cases the amount of pull and the corresponding pain was found to be significant.[202]

Pierre Barbet, a French physician, and the chief surgeon at Saint Joseph's Hospital in Paris,[203] hypothesized that Jesus relaxed his muscles to obtain enough air to utter his last words, in the face of exhaustion asphyxia.[204] Some of Barbet's theories, such as the location of nails, are disputed by Zugibe.

Orthopedic surgeon Keith Maxwell not only analyzed the medical aspects of the crucifixion, but also looked back at how Jesus could have carried the cross all the way along Via Dolorosa.[205][206]

In 2003, historians F. P. Retief and L. Cilliers reviewed the history and pathology of crucifixion as performed by the Romans and suggested that the cause of death was often a combination of factors. They also state that Roman guards were prohibited from leaving the scene until death had occurred.[207]

Theological significance

editChristians believe that Jesus's death was instrumental in restoring humankind to relationship with God.[208][209] Christians believe that through Jesus's death and resurrection[210][211] people are reunited with God and receive new joy and power in this life as well as eternal life. Thus the crucifixion of Jesus along with his resurrection restores access to a vibrant experience of God's presence, love and grace as well as the confidence of eternal life.[212]

Christology

editThe accounts of the crucifixion and subsequent resurrection of Jesus provide a rich background for Christological analysis, from the canonical Gospels to the Pauline epistles.[213] Christians believe Jesus's suffering was foretold in the Old Testament, such as in Psalm 22, and Isaiah 53 prophecy of the suffering servant.[214]

In Johannine "agent Christology" the submission of Jesus to crucifixion is a sacrifice made as an agent of God or servant of God, for the sake of eventual victory.[215][216] This builds on the salvific theme of the Gospel of John which begins in John 1:29 with John the Baptist's proclamation: "The Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world".[217][218]

A central element in the Christology presented in the Acts of the Apostles is the affirmation of the belief that the death of Jesus by crucifixion happened "with the foreknowledge of God, according to a definite plan".[219] In this view, as in Acts 2:23, the cross is not viewed as a scandal, for the crucifixion of Jesus "at the hands of the lawless" is viewed as the fulfillment of the plan of God.[219][220]

Paul's Christology has a specific focus on the death and resurrection of Jesus. For Paul, the crucifixion of Jesus is directly related to his resurrection and the term "the cross of Christ" used in Galatians 6:12 may be viewed as his abbreviation of the message of the gospels.[221] For Paul, the crucifixion of Jesus was not an isolated event in history, but a cosmic event with significant eschatological consequences, as in 1 Corinthians 2:8.[221] In the Pauline view, Jesus, obedient to the point of death (Philippians 2:8) died "at the right time" (Romans 4:25) based on the plan of God.[221] For Paul the "power of the cross" is not separable from the resurrection of Jesus.[221] Furthermore, Paul highlighted the idea that Jesus on the cross defeated the spiritual forces of evil "Kosmokrator", literally 'the rulers of this world' (used in plural in Ephesians 6:12), thus highlighting the idea of victory of light over darkness, or good over evil, through Christ.[222]

Belief in the redemptive nature of Jesus's death predates the Pauline letters, to the earliest days of Christianity and the Church of Jerusalem.[223] The Nicene Creed's statement that "for our sake he was crucified" is a reflection of this core belief's formalization in the fourth century.[224]

John Calvin supported the "agent of God" Christology and argued that in his trial in Pilate's Court Jesus could have successfully argued for his innocence, but instead submitted to crucifixion in obedience to the Father.[225][226] This Christological theme continued into the 20th century, both in the Eastern and Western Christianity. In Eastern Christianity, Sergei Bulgakov argued, the crucifixion of Jesus was "pre-eternally" determined by the Father before the creation of the world, to redeem humanity from the disgrace caused by the fall of Adam.[227] In Western Christianity, Karl Rahner elaborated on the analogy that the blood of the Lamb of God (and the water from the side of Jesus) shed at the crucifixion had a cleansing nature, similar to baptismal water.[228]

Atonement

editJesus's death and resurrection underpin a variety of theological interpretations as to how salvation is granted to humanity. These interpretations vary widely in how much emphasis they place on the death and resurrection as compared to Jesus's words.[229] According to the substitutionary atonement view, Jesus's death is of central importance, and Jesus willingly sacrificed himself after his resurrection as an act of perfect obedience as a sacrifice of love which pleased God.[230] By contrast, the moral influence theory of atonement focuses much more on the moral content of Jesus's teaching, and sees Jesus's death as a martyrdom.[231] Since the Middle Ages there has been conflict between these two views within Western Christianity. Evangelical Protestants typically hold a substitutionary view and in particular hold to the theory of penal substitution. Liberal Protestants typically reject substitutionary atonement and hold to the moral influence theory of atonement. Both views are popular within the Roman Catholic Church, with the satisfaction doctrine incorporated into the idea of penance.[230]

In the Roman Catholic tradition this view of atonement is balanced by the duty of Roman Catholics to perform the Acts of Reparation to Jesus Christ[232] which in the encyclical Miserentissimus Redemptor of Pope Pius XI were defined as "some sort of compensation to be rendered for the injury" with respect to the sufferings of Jesus.[233] Pope John Paul II referred to these acts of reparation as the "unceasing effort to stand beside the endless crosses on which the Son of God continues to be crucified."[234]

Among Eastern Orthodox Christians, another common view is Christus Victor.[235] This holds that Jesus was sent by God to defeat death and Satan. Because of his perfection, voluntary death, and resurrection, Jesus defeated Satan and death, and arose victorious. Therefore, humanity was no longer bound in sin, but was free to rejoin God through the repentance of sin and faith in Jesus.[236]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints teaches that the crucifixion of Jesus was part of the atonement and a "redeeming ransom" both for the effect of the fall of Adam upon all humankind and "for the personal sins of all who repent, from Adam to the end of the world."[237]

Deicide

editThe Catholic Church denounces the idea of Jewish deicide, believing that all sinners are the authors and ministers of Jesus's crucifixion, and admonishes Christians that their own guilt is greater when they sin with knowledge of Jesus, than when others sin without it.[238][239]

Denial

editDocetism

editIn Christianity, Docetism is the doctrine that the phenomenon of Jesus, his historical and bodily existence, and above all the human form of Jesus, was mere semblance without any true reality.[240] Docetists denied that Jesus could have truly suffered and died, as his physical body was illusory, and instead saw the crucifixion as something that only appeared to happen.[241]

Nag Hammadi manuscripts

editAccording to the First Revelation of James in the Nag Hammadi library, Jesus appeared to James after apparently being crucified and stated that another person had been inflicted in his place:

"The master appeared to him. He stopped praying, embraced him, and kissed him, saying, “Rabbi, I’ve found you. I heard of the sufferings you endured, and I was greatly troubled. You know my compassion. Because of this I wished, as I reflected upon it, that I would never see these people again. They must be judged for what they have done, for what they have done is not right.” The master said, “James, do not be concerned for me or these people. I am the one who was within me. Never did I suffer at all, and I was not distressed. These people did not harm me. Rather, all this was inflicted upon a figure of the rulers, and it was fitting that this figure should be [destroyed] by them."[242]

Islam

editMost Islamic traditions categorically deny that Jesus physically died, either on a cross or another manner. This denial is asserted in the Quran, which states:

And [for] their saying, "Indeed, we have killed the Messiah, Jesus the son of Mary, the messenger of Allah." And they did not kill him, nor did they crucify him; but rather, it was made to appear to them so. And indeed, those who differ over it are in doubt about it. They have no knowledge of it except the following of assumption. And they did not kill him, for certain. (157) Rather, Allah raised him to Himself. And ever is Allah Exalted in Might and Wise. (158)

Islamic traditions teach that Jesus ascended to Heaven without being put on the cross, but that God transformed another person to appear exactly like him and to be then crucified instead of him. An ancient antecedent of this view is attested in an account by Irenaeus of the doctrine of the 2nd-century Alexandrian Gnostic Basilides, in which Irenaeus refutes what he believes to be a heresy denying the death.[244]

Gnosticism

editSome scriptures identified as Gnostic reject the atonement of Jesus's death by distinguishing the earthly body of Jesus and his divine and immaterial essence. According to the Second Treatise of the Great Seth, Yaldabaoth (the Creator of the material universe) and his Archons tried to kill Jesus by crucifixion, but only killed their own man (that is the body). While Jesus ascended from his body, Yaldabaoth and his followers thought Jesus to be dead.[245][246] In Apocalypse of Peter, Peter talks with the savior whom the "priests and people" believed to have killed.[247]

Manichaeism, which was influenced by Gnostic ideas, adhered to the idea that not Jesus, but somebody else was crucified instead.[248]: 41 Jesus suffering on the cross is depicted as the state of light particles (spirit) within matter instead.[249]

According to Bogomilism, the crucifixion was an attempt by Lucifer to destroy Jesus, while the earthly Jesus was regarded as a prophet, Jesus himself was an immaterial being that can not be killed. Accordingly, Lucifer failed and Jesus's sufferings on the cross were only an illusion.[250]

Others

editAccording to some Christian sects in Japan, Jesus Christ did not die on the cross at Golgotha. Instead his younger brother, Isukiri,[251] took his place on the cross, while Jesus fled across Siberia to Mutsu Province, in northern Japan. Once in Japan, he became a rice farmer, married, and raised a family with three daughters near what is now Shingō. While in Japan, it is asserted that he traveled, learned, and eventually died at the age of 106. His body was exposed on a hilltop for four years. According to the customs of the time, Jesus's bones were collected, bundled, and buried in a mound.[252][253] There is also a museum in Japan which claims to have evidence of these claims.[254]

In Yazidism, Jesus is thought of as a "figure of light" who could not be crucified. This interpretation could be either taken from the Quran or Gnostics.[255]

In art, symbolism and devotions

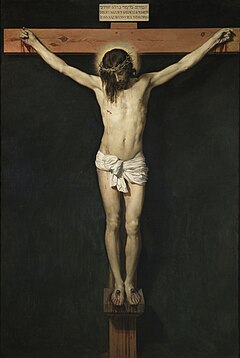

editSince the crucifixion of Jesus, the cross has become a key element of Christian symbolism, and the crucifixion scene has been a key element of Christian art, giving rise to specific artistic themes such as Christ Carrying the Cross, raising of the Cross, Stabat Mater, Descent from the Cross and Lamentation of Christ.

The symbolism of the cross which is today one of the most widely recognized Christian symbols was used from the earliest Christian times. Justin Martyr, who died in 165, describes it in a way that already implies its use as a symbol, although the crucifix appeared later.[256][257]

Devotions based on the process of crucifixion, and the sufferings of Jesus are followed by various Christians. The Stations of the Cross follows a number of stages based on the stages involved in the crucifixion of Jesus, while the Rosary of the Holy Wounds is used to meditate on the wounds of Jesus as part of the crucifixion.

Masters such as Giotto, Fra Angelico, Masaccio, Raphael, Botticelli, van Dyck, Titian, Caravaggio, El Greco, Zurbarán, Velázquez, Rubens and Rembrandt have all depicted the crucifixion scene in their works. The Crucifixion, seen from the Cross by Tissot presented a novel approach at the end of the 19th century, in which the crucifixion scene was portrayed from the perspective of Jesus.[258][259]

The presence of the Virgin Mary under the cross, mentioned in the Gospel of John,[260] has in itself been the subject of Marian art, and well known Catholic symbolism such as the Miraculous Medal and Pope John Paul II's Coat of Arms bearing a Marian Cross. And a number of Marian devotions also involve the presence of the Virgin Mary in Calvary, e.g., Pope John Paul II stated that "Mary was united to Jesus on the Cross".[261][262] Well known works of Christian art by masters such as Raphael (the Mond Crucifixion), and Caravaggio (The Entombment of Christ) depict the Virgin Mary as part of the crucifixion scene.

-

Crucifixion of Christ, Michelangelo, 1540

-

Print of Albrecht Dürer's Die Kreuzigung, printed at the end of the 16th century[263]

-

Calvary by Paolo Veronese, 16th century

-

From a 14th–15th century Welsh manuscript

-

Crucifix of Taguig Church, Philippines

-

Crucified Jesus at the Ytterselö church, Sweden, c. 1500

-

Crucifixion, Markazini, 1647

-

Descent from the Cross, Rubens, 1616–17

-

Descent from the Cross, Raphael, 1507

See also

edit- The penitent thief and impenitent thief, crucified alongside Jesus

- Descriptions in antiquity of the execution cross

- True Cross

- Shroud of Turin

- Sudarium of Oviedo

- Feast of the Cross

- Golgotha

- Life of Jesus in the New Testament

- Seven Sorrows of Mary

- Swoon hypothesis

- Depictions of Jesus

- Calvary

- Stations of the Cross

Notes

edit- ^ The instrument of crucifixion is generally taken to have been composed of an upright wooden beam to which was added a transverse wooden beam, thus forming a "cruciform" or T-shaped structure.

- ^ Historicity:

- Dunn (2003, p. 339) states that these "two facts in the life of Jesus command almost universal assent" and "rank so high on the 'almost impossible to doubt or deny' scale of historical facts" that they are often the starting points for the study of the historical Jesus.

- ^ Non-Christian sources:

- Crossan (1995, p. 145): "That he was crucified is as sure as anything historical can ever be, since both Josephus and Tacitus ... agree with the Christian accounts on at least that basic fact.

- Eddy & Boyd (2007, p. 127) state that it is now "firmly established" that there is non-Christian confirmation of the crucifixion of Jesus.

References

edit- ^ Eddy, Paul Rhodes and Gregory A. Boyd (2007). The Jesus Legend: A Case for the Historical Reliability of the Synoptic Jesus Tradition. Baker Academic. p. 172. ISBN 978-0801031144.

...if there is any fact of Jesus' life that has been established by a broad consensus, it is the fact of Jesus' crucifixion.

- ^ Christopher M. Tuckett in The Cambridge companion to Jesus edited by Markus N. A. Bockmuehl 2001 Cambridge Univ Press ISBN 978-0-521-79678-1 pp. 123–124

- ^ Funk, Robert W.; Jesus Seminar (1998). The acts of Jesus: the search for the authentic deeds of Jesus. San Francisco: Harper. ISBN 978-0060629786.

- ^ a b Blomberg (2009), p. 211–214.

- ^ International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. vol. К-Р, Р. 979.

- ^ a b The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament by Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum 2009 ISBN 978-0-8054-4365-3 pp. 104–108

- ^ a b Evans, Craig A. (2001). Jesus and His Contemporaries: Comparative Studies ISBN 0-391-04118-5 p. 316

- ^ Wansbrough, Henry (2004). Jesus and the Oral Gospel Tradition ISBN 0-567-04090-9 p. 185

- ^ Davis, C. Truman (November 4, 2015). "A Physician's View of the Crucifixion of Jesus Christ". The Christian Broadcasting Network. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- ^ Byrskog, Samuel (2011). "The Historicity of Jesus: How do we now that Jesus existed?". Handbook for the Study of the Historical Jesus (Volume 3). Brill. p. 2190. ISBN 978-9004163720.

- ^ a b Davies, W. D.; Sanders, E.P. (2008). "20. Jesus: From the Jewish Point of View". In Horbury, William; Davies, W.D.; Sturdy, John (eds.). The Cambridge History of Judaism. Volume 3: The Early Roman period. Cambridge Univiversity Press. p. 621. ISBN 9780521243773.

The approximate period of his death (c. CE 30, plus or minus one or two years) is confirmed by the requirements of the chronology of Paul.

- ^ Matthew 26:46–27:60; Mark 14:43–15:45; Luke 22:47–23:53; John 18:3–19:42

- ^ St Mark's Gospel and the Christian faith by Michael Keene (2002) ISBN 0-7487-6775-4 pp. 24–25

- ^ Powell, Mark A. Introducing the New Testament. Baker Academic, (2009). ISBN 978-0-8010-2868-7

- ^ Reza Aslan (2014). Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth. Random House. ISBN 0812981480.

- ^ Mark 15:25

- ^ Mark 15:34–37

- ^ Ehrman, Bart D. (2009). Jesus, Interrupted. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-117393-2

- ^ Matthew 26:51–53

- ^ Matthew 27:31–32; Mark 15:20–21; Luke 23:26

- ^ Matthew 27:39–43; Mark 15:29–32; Luke 23:35–37

- ^ Matthew 27:44; Mark 15:32; Luke 23:39

- ^ Matthew 27:45; Mark 15:33; Luke 23:44–45

- ^ Matthew 27:51; Mark 15:38; Luke 23:45

- ^ Matthew 27:54; Mark 15:39; Luke 23:47

- ^ Matthew 27:55–56; Mark 15:40–41; Luke 23:49

- ^ Matthew 27:61; Mark 15:47; Luke 23:54–55

- ^ Matthew 27:34; 27:47–49; Mark 15:23; 15:35–36; John 19:29–30

- ^ Mark 15:45; John 19:38

- ^ Matthew 27:51; 27:62–66

- ^ Ray, Steve. "When Was Jesus Crucified? How Long on the Cross? Do the Gospels Contradict Each Other?". Defenders of the Catholic Faith. Archived from the original on August 28, 2019. Retrieved August 10, 2019.

- ^ Mark 15:25; 15:44–45

- ^ Luke 23:27–32; 23:40–41; 23:48; 23:56

- ^ John 19:31–37; 19:39–40

- ^ John 19:30–31; Mark 16:1; Mark 16:6

- ^ Geza Vermes, The Resurrection (Penguin, 2008), p. 148.

- ^ E. P. Sanders, The Historical Figure of Jesus (Penguin, 1993), p. 276.

- ^ Donald Guthrie, New Testament Introduction (Intervarsity, 1990), pp. 125, 366.

- ^ a b c d Funk, Robert W. and the Jesus Seminar (1998). The Acts of Jesus: The Search for the Authentic Deeds of Jesus. HarperSanFrancisco. "Mark", pp. 51–161. ISBN 978-0060629786.

- ^ a b Funk, Robert W. and the Jesus Seminar (1998). The Acts of Jesus: The Search for the Authentic Deeds of Jesus. HarperSanFrancisco. "Matthew," pp. 129–270. ISBN 978-0060629786.

- ^ a b Funk, Robert W. and the Jesus Seminar (1998). The Acts of Jesus: The Search for the Authentic Deeds of Jesus. HarperSanFrancisco. "Luke", pp. 267–364. ISBN 978-0060629786.

- ^ Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-073817-4.

- ^ Funk, Robert W. and the Jesus Seminar (1998). The Acts of Jesus: The Search for the Authentic Deeds of Jesus. HarperSanFrancisco. "John", pp. 365–440. ISBN 978-0060629786.

- ^ a b In verse 19:17 and 19:18, only a third person plural verb is used ("they"), it is not clear whether this refers to the high priests (οἱ ἀρχιερεῖς) to whom Pilate delivered Jesus in 19:15–16, or to the soldiers (οὖν στρατιῶται) who crucified Jesus according to 19:23.

- ^ In some manuscripts of Luke, these words are omitted. Annotation Nieuwe Bijbelvertaling (2004).

- ^ a b Based on other Biblical verses, it is often concluded that this Mary was Jesus's own mother, and that James and Joses/Joseph were his brothers, see brothers of Jesus.

- ^ a b c Evidence of Greek Philosophical Concepts in the Writings of Ephrem the Syrian by Ute Possekel 1999 ISBN 90-429-0759-2 pp. 29–30

- ^ a b Studying the Historical Jesus: Evaluations of the State of Current Research edited by Bruce Chilton, Craig A. Evans 1998 ISBN 90-04-11142-5 pp. 455–457

- ^ a b The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament by Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum 2009 ISBN 978-0-8054-4365-3 p. 110

- ^ a b Jesus outside the New Testament: an introduction to the ancient evidence by Robert E. Van Voorst 2000 ISBN 0-8028-4368-9 pp. 53–55

- ^ Evans, Craig A. (2001). Jesus and His Contemporaries: Comparative Studies. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-391-04118-9.

- ^ a b Theissen 1998, pp. 81–83

- ^ Dunn, James (2003). Jesus remembered. ISBN 0-8028-3931-2. p. 141.

- ^ a b Van Voorst, Robert E (2000). Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 0-8028-4368-9. pp. 39–42.

- ^ Ferguson, Everett (2003). Backgrounds of Early Christianity. ISBN 0-8028-2221-5. p. 116.

- ^ Green, Joel B. (1997). The Gospel of Luke: new international commentary on the New Testament. Grand Rapids, Mich.: W. B. Eerdmans Pub. Co. p. 168. ISBN 0-8028-2315-7. Archived from the original on April 7, 2023. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- ^ Jesus as a Figure in History: How Modern Historians View the Man from Galilee by Mark Allan Powell, 1998, ISBN 0-664-25703-8. p. 33.

- ^ Jesus and His Contemporaries: Comparative Studies by Craig A. Evans. 2001. ISBN 0-391-04118-5. p. 42.

- ^ Ancient Rome by William E. Dunstan 2010 ISBN 0-7425-6833-4 p. 293

- ^ Tacitus' characterization of "Christian abominations" may have been based on the rumors in Rome that during the Eucharist rituals Christians ate the body and drank the blood of their God, interpreting the symbolic ritual as cannibalism by Christians. References: Ancient Rome by William E. Dunstan 2010 ISBN 0-7425-6833-4 p. 293 and An introduction to the New Testament and the origins of Christianity by Delbert Royce Burkett 2002 ISBN 0-521-00720-8 p. 485

- ^ Pontius Pilate in History and Interpretation by Helen K. Bond 2004 ISBN 0-521-61620-4 p. xi

- ^ Eddy & Boyd (2007), p. 127.

- ^ Jesus in the Talmud by Peter Schäfer (2009) ISBN 0-691-14318-8 pp. 141 and 9

- ^ Van Voorst, Robert E. (2000). Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. pp. 177–118. ISBN 0-8028-4368-9.

- ^ Gil Student (2000). "The Jesus Narrative In The Talmud". Talmud: The Real Truth About the Talmud. Archived from the original on January 30, 2020. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ L. Patterson, "Origin of the Name Panthera", JTS 19 (1917–18), pp. 79–80, cited in Meier, p. 107 n. 48

- ^ a b George W. Braswell Jr., What You Need to Know about Islam and Muslims Archived November 23, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, p. 127 (B & H Publishing Group, 2000). ISBN 978-0-8054-1829-3.

- ^ Dunderberg, Ismo; Tuckett, Christopher Mark; Syreeni, Kari (2002). Fair play: diversity and conflicts in early Christianity: essays in honour of Heikki Räisänen. Brill. p. 488. ISBN 90-04-12359-8. Archived from the original on April 7, 2023. Retrieved November 28, 2015.

- ^ Pagels, Elaine H. (2006). The Gnostic gospels. Phoenix. p. 192. ISBN 0-7538-2114-1.

- ^ Barclay, William (2001). Great Themes of the New Testament. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-664-22385-4.

- ^ "St. Ignatius of Antioch to the Smyrnaeans (Roberts-Donaldson translation)". www.earlychristianwritings.com. Archived from the original on March 23, 2016. Retrieved March 10, 2012.

- ^ Dunn (2003), p. 339.

- ^ Ehrman (2008), p. 136.

- ^ a b c Meier (2006), p. 126–128.

- ^ Verhoeven (2010), p. 39.

- ^ a b Meier (2006), p. 132–136.

- ^ Tuckett (2001), p. 136.

- ^ a b Nicholson, Ernest, ed. (2004). A Century of Theological and Religious Studies in Britain, 1902–2007. pp. 125–126. ISBN 0-19-726305-4. Archived from the original on November 23, 2022.

- ^ Barber, Michael (2020). "Did Jesus Anticipate Suffering a Violent Death?: The Implications of Memory Research and Dale C. Allison's Methodology". Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus (18:3): 191-219. doi:10.1163/17455197-01803002.

- ^ Ferda, Tucker (2024). Jesus and His Promised Second Coming: Jewish Eschatology and Christian Origins. Eerdmans. p. 47. ISBN 9780802879905.

- ^ Erhman, Bart (1999). Jesus:the apocalyptic prophet of the new millenium. Oxford University Press. p. 222. ISBN 9780195124743.

- ^ David Freedman (2000), Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible, ISBN 978-0-8028-2400-4, p. 299.

- ^ Zukeran, Pat. "Archaeology and the New Testament". Probe Ministries International. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved February 18, 2009.

- ^ "Crucifixion". AllAboutJesusChrist.org. Archived from the original on April 5, 2022. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ David, Ariel (October 12, 2020). "Are These Nails From Jesus' Crucifixion? New Evidence Emerges, but Experts Are Unconvinced". Haaretz. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ Lémonon, J.P. (1981). Pilate et le gouvernement de la Judée: textes et monuments, Études bibliques. Paris: Gabalda. pp. 29–32.

- ^ Paul L. Maier "The Date of the Nativity and Chronology of Jesus" in Chronos, kairos, Christos: nativity and chronological studies by Jerry Vardaman, Edwin M. Yamauchi 1989 ISBN 0-931464-50-1 pp. 113–129

- ^ The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament by Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum 2009 ISBN 978-0-8054-4365-3 p. 114

- ^ Jesus & the Rise of Early Christianity: A History of New Testament Times by Paul Barnett 2002 ISBN 0-8308-2699-8 pp. 19–21

- ^ Rainer Riesner, Paul's Early Period: Chronology, Mission Strategy, Theology (Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1998), p. 58.

- ^ Maier, P.L. (1968). "Sejanus, Pilate, and the Date of the Crucifixion". Church History. 37 (1): 3–13. doi:10.2307/3163182. JSTOR 3163182. S2CID 162410612.

- ^ Fotheringham, J.K. (1934). "The evidence of astronomy and technical chronology for the date of the crucifixion". Journal of Theological Studies. 35 (138): 146–162. doi:10.1093/jts/os-XXXV.138.146.

- ^ The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament by Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum 2009 ISBN 978-0-8054-4365-3 pp. 142–143

- ^ Cyclopaedia of Biblical, theological, and ecclesiastical literature: Volume 7 John McClintock, James Strong – 1894 "... he lay in the grave on the 15th (which was a 'high day' or double Sabbath, because the weekly Sabbath coincided ..."

- ^ "Blomberg "Wednesday crucifixion" – Google Search". www.google.ie. Archived from the original on April 6, 2022. Retrieved April 7, 2023.

- ^ The Gospel of Mark, Volume 2 by John R. Donahue, Daniel J. Harrington 2002 ISBN 0-8146-5965-9 p. 442

- ^ a b c Cox, Steven L.; Easley, Kendell H (2007). Harmony of the Gospels. p. 323. ISBN 0-8054-9444-8.

- ^ Death of the Messiah, Volume 2 by Raymond E. Brown 1999 ISBN 0-385-49449-1 pp. 959–960

- ^ Colin Humphreys, The Mystery of the Last Supper Cambridge University Press 2011 ISBN 978-0-521-73200-0, pp. 188–190

- ^ Niswonger, Richard L. (1992). New Testament History. pp. 173–174. ISBN 0-310-31201-9.

- ^ Köstenberger, Andreas J.; Kellum, L. Scott (2009). The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament. p. 538. ISBN 978-0-8054-4365-3.

- ^ Matthew 27:32, Mark 15:21, Luke 23:26

- ^ Jn. 19:17

- ^ Lk. 23:28–31

- ^ Luke 23:46 and 23:55

- ^ Lavinia Cohn-Sherbok, Who's who in Christianity, (Routledge 1998), p. 303.

- ^ Notes and Queries, Volume July 6 – December 1852, London, page 252

- ^ The Archaeological journal (UK), Volume 7, 1850 p. 413

- ^ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: St. Veronica". www.newadvent.org. Archived from the original on April 3, 2022. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ Alban Butler, 2000 Lives of the Saints ISBN 0-86012-256-5 p. 84

- ^ Jn. 19:20, Heb. 13:12

- ^ Mt. 27:39, Mk. 15:21,29–30

- ^ Mk. 15:40

- ^ Eusebius of Caesarea. Onomasticon (Concerning the Place Names in Sacred Scripture). Archived from the original on July 17, 2019. Retrieved April 10, 2008.

- ^ Matthew 27:33; Mark 15:22; Luke 23:33; John 19:17

- ^ Eucherius of Lyon. "Letter to the Presbyter Faustus". Archived from the original on June 13, 2008.

The three more frequented exit gates are one on the west, another on the east, and a third on the north. As you enter the city from the northern side, the first of the holy places due to the condition of the directions of the streets is to the church which is called the Martyrium, which was by Constantine with great reverence not long ago built up. Next, to the west one visits the connecting places Golgotha and the Anastasis; indeed the Anastasis is in the place of the resurrection, and Golgotha is in the middle between the Anastasis and the Martyrium, the place of the Lord's passion, in which still appears that rock which once endured the very cross on which the Lord was. These are separated places outside of Mount Sion, where the failing rise of the place extended itself to the north.

- ^ "General Charles Gordon's Letters Discussing His Discovery of "Cavalry" in Jerusalem". SMF Primary Source Documents. Shapell Manuscript Foundation.

- ^ Mark 15:40

- ^ Matthew 27:55–56

- ^ a b Luke 23:49

- ^ John 19:25

- ^ Matthew 27:41, Mark 15:31, Luke 23:35

- ^ Mark 15:27, Matthew 27:38

- ^ Luke 23:36

- ^ Matthew 27:54, Mark 15:39

- ^ Mark 15:29, Matthew 27:39

- ^ Mark 15:35, Matthew 27:45, Luke 23:35

- ^ Luke 23:48

- ^ Luke 23:39–43

- ^ John 19:23–24, 19:32–34

- ^ John 19:26–27

- ^ Mark 16:43–46, Matthew 27:57–50, Luke 23:50–53, John 19:38

- ^ John 19:39

- ^ Henry George Liddell; Robert Scott. "σταυρός". A Greek–English Lexicon. Archived from the original on March 7, 2008. Retrieved February 20, 2021 – via Tufts University.

- ^ Charlton T. Lewis; Charles Short. "A Latin Dictionary". Archived from the original on December 31, 2016. Retrieved January 15, 2019 – via Tufts University.

- ^ For a discussion of the date of the work, see Information on Epistle of Barnabas Archived March 16, 2010, at the Wayback Machine and Andrew C. Clark, "Apostleship: Evidence from the New Testament and Early Christian Literature," Evangelical Review of Theology, 1989, Vol. 13, p. 380

- ^ John Dominic Crossan, The Cross that Spoke (ISBN 978-0-06-254843-6), p. 121

- ^ Epistle of Barnabas, 9:7–8

- ^ "The Spirit saith to the heart of Moses, that he should make a type of the cross and of Him that was to suffer, that unless, saith He, they shall set their hope on Him, war shall be waged against them for ever. Moses therefore pileth arms one upon another in the midst of the encounter, and standing on higher ground than any he stretched out his hands, and so Israel was again victorious" (Epistle of Barnabas, 12:2–3).

- ^ "Philip Schaff: ANF01. The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus – Christian Classics Ethereal Library". www.ccel.org. Archived from the original on April 6, 2022. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ Irenaeus, Adversus Haereses, II, xxiv, 4 Archived April 20, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia by Geoffrey W. Bromiley 1988 ISBN 0-8028-3785-9 p. 826

- ^ a b Encyclopedia of Biblical Literature, Part 2 by John Kitto 2003 ISBN 0-7661-5980-9 p. 591

- ^ a b c Renaissance art: a topical dictionary by Irene Earls 1987 ISBN 0-313-24658-0 p. 64

- ^ The visual arts: a history by Hugh Honour, John Fleming 1995 ISBN 0-8109-3928-2 p. 526

- ^ The Crucifixion and Death of a Man Called Jesus by David A Ball 2010 ISBN 1-61507-128-8 pp. 82–84

- ^ a b The Chronological Life of Christ by Mark E. Moore 2007 ISBN 0-89900-955-7 pp. 639–643

- ^ Holman Concise Bible Dictionary Holman, 2011 ISBN 0-8054-9548-7 p. 148

- ^ Crucifixion and the Death Cry of Jesus Christ by Geoffrey L Phelan MD, 2009 [ISBN missing] pp. 106–111

- ^ Thomas W. Walker, Luke, (Westminster John Knox Press, 2013) p. 84.

- ^ Mt. 27:46, Mk. 15:34

- ^ Caruso, Steve (March 31, 2015). "What is Galilean Aramaic? | The Aramaic New Testament". Aramaicnt.org. Archived from the original on January 22, 2019. Retrieved January 15, 2019.

- ^ Caruso, Steve (March 31, 2015). "My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?". Archived from the original on April 7, 2023. Retrieved April 7, 2023.

- ^ Geza Vermes, The Passion (Penguin, 2005) p. 75.

- ^ Geza Vermes, The Passion (Penguin, 2005) p. 114.

- ^ Geza Vermes, The Passion (Penguin, 2005) p. 122.

- ^ Raymond Brown, The Death of the Messiah Volume II (Doubleday, 1994) p. 1051

- ^ Lk. 23:34

- ^ Lk. 23:43

- ^ Lk. 23:46

- ^ John Haralson Hayes, Biblical Exegesis: A Beginner's Handbook (Westminster John Knox Press, 1987) pp. 104–105. The author suggests this possibly was designed to play down the suffering of Jesus and replace a cry of desperation with one of hope and confidence, in keeping with the message of the Gospel in which Jesus dies confident that he would be vindicated as God's righteous prophet.

- ^ Jn. 19:25–27

- ^ Jn. 19:28

- ^ Jn. 19:30

- ^ David Anderson-Berry, 1871 The Seven Sayings of Christ on the Cross, Glasgow: Pickering & Inglis Publishers

- ^ Rev. John Edmunds, 1855 The seven sayings of Christ on the cross Thomas Hatchford Publishers, London, p. 26

- ^ Arthur Pink, 2005 The Seven Sayings of the Saviour on the Cross Baker Books ISBN 0-8010-6573-9

- ^ Simon Peter Long, 1966 The wounded Word: A brief meditation on the seven sayings of Christ on the cross Baker Books

- ^ John Ross Macduff, 1857 The Words of Jesus New York: Thomas Stanford Publishers, p. 76

- ^ Alexander Watson, 1847 The seven sayings on the Cross John Masters Publishers, London, p. 5. The difference between the accounts is cited by James Dunn as a reason to doubt their historicity. James G. D. Dunn, Jesus Remembered, (Eerdmans, 2003) pp. 779–781.

- ^ Scott's Monthly Magazine Archived November 23, 2022, at the Wayback Machine. J.J. Toon; 1868. The Miracles Coincident With The Crucifixion, by H.P.B. pp. 86–89.

- ^ Richard Watson. An Apology for the Bible: In a Series of Letters Addressed to Thomas Paine Archived November 23, 2022, at the Wayback Machine. Cambridge University Press; 2012. ISBN 978-1-107-60004-1. pp. 81–.

- ^ Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985. "John" pp. 302–310

- ^ Edwin Keith Broadhead Prophet, Son, Messiah: Narrative Form and Function in Mark (Continuum, 1994) p. 196.

- ^ Origen. "Contra Celsum (Against Celsus), Book 2, XXXIII". Archived from the original on January 9, 2019. Retrieved May 5, 2008.

- ^ Donaldson, Coxe (1888). The ante-Nicene fathers. Vol. 6. New York: The Christian Literature Publishing Co. p. 136. Archived from the original on April 7, 2023. Retrieved November 28, 2015.

- ^ "In the same hour, too, the light of day was withdrawn, when the sun at the very time was in his meridian blaze. Those who were not aware that this had been predicted about Christ, no doubt thought it an eclipse. You yourselves have the account of the world-portent still in your archives."Tertullian. "Apologeticum". Archived from the original on April 6, 2022. Retrieved May 5, 2008.

- ^ Colin J. Humphreys and W. G. Waddington, The Date of the Crucifixion Journal of the American Scientific Affiliation 37 (March 1985).

- ^ Colin Humphreys, The Mystery of the Last Supper Cambridge University Press 2011 ISBN 978-0-521-73200-0, p. 193

- ^ Henige, David P. (2005). Historical evidence and argument. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-21410-4.

- ^ Schaefer, B. E. (March 1990). Lunar visibility and the crucifixion. Royal Astronomical Society Quarterly Journal, 31(1), 53–67

- ^ Schaefer, B. E. (July 1991). Glare and celestial visibility. Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 103, 645–660.

- ^ "BBC Radio 4 – in Our Time, Eclipses". Archived from the original on April 6, 2022. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- ^ Burton L. Mack, A Myth of Innocence: Mark and Christian Origins (Fortress Press, 1988) p. 296; George Bradford Caird, The language and imagery of the Bible (Westminster Press, 1980), p. 186; Joseph Fitzmyer, The Gospel According to Luke, X–XXIV (Doubleday, 1985) p. 1513; William David Davies, Dale Allison, Matthew: Volume 3 (Continuum, 1997) p. 623.

- ^ David E. Garland, Reading Matthew: A Literary and Theological Commentary on the First Gospel (Smyth & Helwys Publishing, 1999) p. 264.

- ^ Géza Vermes, The Passion (Penguin, 2005) pp. 108–109.

- ^ Mt. 27:51–53

- ^ Mk. 15:39

- ^ Mt. 27:54

- ^ Lk. 23:47

- ^ New Revised Standard Version; New International Version renders "...this was a righteous man".

- ^ George Syncellus, Chronography, chapter 391 Archived April 11, 2021, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Jefferson Williams, Markus Schwab and Achim Brauer (July 2012). "An early first-century earthquake in the Dead Sea'". International Geology Review. 54 (10): 1219–1228. Bibcode:2012IGRv...54.1219W. doi:10.1080/00206814.2011.639996. S2CID 129604597.

- ^ Medical theories on the cause of death in Crucifixion J R Soc Med April 2006 vol. 99 no. 4 185–188. [1] Archived September 12, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ William Stroud, 1847, Treatise on the Physical Death of Jesus Christ London: Hamilton and Adams.

- ^ Seymour, William (2003). The Cross in Tradition, History and Art. ISBN 0-7661-4527-1.

- ^ The Physical Death Of Jesus Christ, Study by The Mayo Clinic Archived January 31, 2009, at the Wayback Machine citing studies by Bucklin R (The legal and medical aspects of the trial and death of Christ. Sci Law 1970; 10:14–26), Mikulicz-Radeeki FV (The chest wound in the crucified Christ. Med News 1966; 14:30–40), Davis CT (The Crucifixion of Jesus: The passion of Christ from a medical point of view. Ariz Med 1965; 22:183–187), and Barbet P (A Doctor at Calvary: The Passion of Out Lord Jesus Christ as Described by a Surgeon, Earl of Wicklow (trans) Garden City, NY, Doubleday Image Books 1953, pp. 12–18, 37–147, 159–175, 187–208).

- ^ 19:34

- ^ Edwards, William D.; Gabel, Wesley J.; Hosmer, Floyd E; On the Physical Death of Jesus, JAMA March 21, 1986, Vol 255, No. 11, pp. 1455–1463 [2] Archived January 26, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Frederick Zugibe, 2005, The Crucifixion of Jesus: A Forensic Inquiry Evans Publishing, ISBN 1-59077-070-6

- ^ JW Hewitt, The Use of Nails in the Crucifixion Harvard Theological Review, 1932

- ^ a b "EXPERIMENTAL STUDIES in CRUCIFIXION". www.crucifixion-shroud.com. Archived from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved January 20, 2009.

- ^ New Scientist October 12, 1978, p. 96

- ^ Barbet, Pierre. Doctor at Calvary, New York: Image Books, 1963.

- ^ "Keith Maxwell MD on the Crucifixion of Christ". Archived from the original on January 17, 2011.

- ^ "Jesus' Suffering and Crucifixion from a Medical Point of View". Southasianconnection.com. April 7, 2007. Archived from the original on June 8, 2019. Retrieved January 15, 2019.

- ^ Retief, FP; Cilliers, L. (December 2003). "The history and pathology of crucifixion". South African Medical Journal = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Geneeskunde. 93 (12): 938–841. PMID 14750495. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church. Urbi et Orbi Communications. 1994. ISBN 978-1-884660-01-6.

- ^ Schwarz, Hans (1996). True Faith in the True God: An Introduction to Luther's Life and Thought. Augsburg. ISBN 978-1-4514-0930-7.

- ^ Benedict XVI, Pope (1987). Principles of Catholic Theology: Building Stones for a Fundamental Theology. San Francisco: Ignatius Press. pp. 17–18.

- ^ Calvin, Jean (1921). Institutes of the Christian Religion. Presbyterian Board of Publication and Sabbath-School Work.

- ^ Kempis, Thomas a (September 6, 2005). The Inner Life. Penguin. ISBN 978-1-101-65142-1.

- ^ Who do you say that I am? Essays on Christology by Mark Allan Powell and David R. Bauer 1999 ISBN 0-664-25752-6 p. 106

- ^ Cross, Frank L.; Livingstone, Elizabeth A. (2005). "The Passion". The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ The Christology of the New Testament by Oscar Cullmann 1959 ISBN 0-664-24351-7 p. 79

- ^ The Johannine exegesis of God by Daniel Rathnakara Sadananda 2005 ISBN 3-11-018248-3 p. 281

- ^ Johannine Christology and the Early Church by T. E. Pollard 2005 ISBN 0-521-01868-4 p. 21

- ^ Studies in Early Christology by Martin Hengel 2004 ISBN 0-567-04280-4 p. 371

- ^ a b New Testament christology by Frank J. Matera 1999 ISBN 0-664-25694-5 p. 67

- ^ The speeches in Acts: their content, context, and concerns by Marion L. Soards 1994 ISBN 0-664-25221-4 p. 34

- ^ a b c d Christology by Hans Schwarz 1998 ISBN 0-8028-4463-4 pp. 132–134

- ^ "War Between Good and Evil – Light from the Cross". Archived from the original on October 28, 2022. Retrieved October 28, 2022.

- ^ Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity by Larry W. Hurtado (2005) ISBN 0-8028-3167-2 pp. 130–133

- ^ Christian Theology by J. Glyndwr Harris (2002) ISBN 1-902210-22-0 pp. 12–15

- ^ Calvin's Christology by Stephen Edmondson 2004 ISBN 0-521-54154-9 p. 91