A javelin is a light spear designed primarily to be thrown, historically as a ranged weapon. Today, the javelin is predominantly used for sporting purposes such as the javelin throw. The javelin is nearly always thrown by hand, unlike the sling, bow, and crossbow, which launch projectiles with the aid of a hand-held mechanism. However, devices do exist to assist the javelin thrower in achieving greater distances, such as spear-throwers or the amentum.

A warrior or soldier armed primarily with one or more javelins is a javelineer.

The word javelin comes from Middle English and it derives from Old French javelin, a diminutive of javelot, which meant spear. The word javelot probably originated from one of the Celtic languages.

Prehistory

editThere is archaeological evidence that javelins and throwing sticks were already in use by the last phase of the Lower Paleolithic. Seven spear-like objects were found in a coal mine in the city of Schöningen, Germany. Stratigraphic dating indicates that the weapons are about 400,000 years old.[1] The excavated items were made of spruce (Picea) trunk and were between 1.83 and 2.25 metres (6.0 and 7.4 ft) long. They were manufactured with the maximum thickness and weight situated at the front end of the wooden shaft. The frontal centre of gravity suggests that these weapons were used as javelins. A fossilized horse shoulder blade with a projectile wound, dated to 500,000 years ago, was revealed in a gravel quarry in the village of Boxgrove, England. Studies suggested that the wound was probably caused by a javelin.[2][3][4]

Classical age

editAncient Egypt

editIn History of Ancient Egypt: Volume 1 (1882), George Rawlinson depicts the javelin as an offensive weapon used by the Ancient Egyptian military. It was lighter in weight than that used by other nations. He describes the Ancient Egyptian javelin's features:

It consisted of a long thin shaft, sometimes merely pointed, but generally armed with a head, which was either leaf-shaped, or like the head of a spear, or else four-sided, and attached to the shaft by projections at the angles.[5]

A strap or tasseled head was situated at the lower end of the javelin: it allowed the javelin thrower to recover his javelin after throwing it.[5]

Egyptian military trained from a young age in special military schools.[6] Focusing on gymnastics to gain strength, hardiness, and endurance in childhood, they learned to throw the javelin – along with practicing archery and the battle-axe – when they grew older, before entering a specific regiment.[7]

Javelins were carried by Egyptian light infantry, as a main weapon, and as an alternative to a bow or spear, generally along with a shield. They also carried a curved sword, club, or hatchet as a sidearm.[8] An important part in battles is often assigned to javelin-men, "whose weapons seem to inflict death at every blow".[9]

Multiple javelins were also sometimes carried by Egyptian war-chariots, in a quiver and/or bow case.[10]

Beyond its military purpose, the javelin was likely also a hunting instrument, for food and sport.[11]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2009) |

Ancient Greece

editThe peltasts, usually serving as skirmishers, were armed with several javelins, often with throwing straps to increase stand-off power. The peltasts hurled their javelins at the enemy's heavier troops, the hoplite phalanx, in order to break their lines so that their own army's hoplites could destroy the weakened enemy formation. In the battle of Lechaeum, the Athenian general Iphicrates took advantage of the fact that a Spartan hoplite phalanx operating near Corinth was moving in the open field without the protection of any missile-throwing troops. He decided to ambush it with his force of peltasts. By launching repeated hit-and-run attacks against the Spartan formation, Iphicrates and his men were able to wear the Spartans down, eventually routing them and killing just under half. This marked the first recorded occasion in ancient Greek military history in which a force entirely made up of peltasts had defeated a force of hoplites.

The thureophoroi and thorakitai, who gradually replaced the peltasts, carried javelins in addition to a long thrusting spear and a short sword.

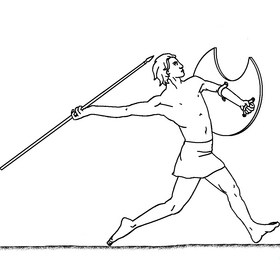

Javelins were often used as an effective hunting weapon, the strap adding enough power to take down large game. Javelins were also used in the Ancient Olympics and other Panhellenic games. They were hurled in a certain direction and whoever hurled it the farthest, as long as it hit tip-first, won that game.

Ancient Rome

editRepublic and early empire

editIn 387 BC, the Gauls invaded Italy, inflicted a crushing defeat on the Roman Republican army, and sacked Rome. After this defeat, the Romans undertook a comprehensive reform of their army and changed the basic tactical formation from the Greek-style phalanx armed with the hasta spear and the clipeus round shield to a more flexible three-line formation. The hastati stood in the first line, the principes in the second line and the triarii in the third line. While the triarii were still armed with hastae, the hastati and the principes were rearmed with short swords and heavy javelins. Each soldier from the hastati and principes lines carried two javelins. This heavy javelin, known as a pilum (plural pila), was about two metres long overall, consisting of an iron shank, about 7 mm in diameter and 60 cm long, with pyramidal head, secured to a wooden shaft. The iron shank was either socketed or, more usually, widened to a flat tang. A pilum usually weighed between 0.9 and 2.3 kilograms (2.0 and 5.1 lb),[citation needed] with the versions produced during the empire being somewhat lighter. Pictorial evidence suggests that some versions of the weapon were weighted with a lead ball at the base of the shank in order to increase penetrative power, but no archaeological specimens have been found.[12] Recent experiments have shown pila to have a range of about 30 metres (98.4 ft), although the effective range is only 15 and 20 metres (49.2 and 65.6 ft). Pila were sometimes referred to as "javelins", but the archaic term for the javelin was "verutum".

From the third century BC, the Roman legion added a skirmisher type of soldier to its tactical formation. The velites were light infantry armed with short swords (the gladius or pugio), small round shields, and several small javelins. These javelins were called "veruta" (singular verutum). The velites typically drew near the enemy, hurled javelins against their formation, and then retreated behind the legion's heavier infantry. The velites were considered highly effective in turning back war elephants, on account of discharging a hail of javelins at some range and not presenting a "block" that could be trampled on or otherwise smashed – unlike the close-order infantry behind them. At the Battle of Zama in 202 BC, the javelin-throwing velites proved their worth and were no doubt critical in helping to herd Hannibal's war elephants through the formation to be slaughtered. The velites would slowly have been either disbanded or re-equipped as more-heavily armed legionaries from the time when Gaius Marius and other Roman generals reorganised the army in the late second and early first centuries BC. Their role would most likely have been taken by irregular auxiliary troops as the republic expanded overseas. The verutum was a cheaper missile weapon than the pilum. The verutum was a short-range weapon, with a simply made head of soft iron.

Legionaries of the late republic and early empire often carried two pila, with one sometimes being lighter than the other. Standard tactics called for a Roman soldier to throw his pilum (both if there was time) at the enemy just before charging to engage with his gladius. Some pila had small hand-guards, to protect the wielder if he intended to use it as a melee weapon, but it does not appear that this was common.

Late Empire

editIn the late Roman Empire, the Roman infantry came to use a differently-shaped javelin from the earlier pilum. This javelin was lighter and had a greater range. Called a plumbata, it resembled a thick stocky arrow, fletched with leather vanes to provide stability and rotation in flight (which increased accuracy). To overcome its comparatively small mass, the plumbata was fitted with an oval-shaped lead weight socketed around the shaft just forward of the center of balance, giving the weapon its name. Even so, plumbatae were much lighter than pila, and would not have had the armour penetration or shield transfixing capabilities of their earlier counterparts.

Two or three plumbatae were typically clipped to a small wooden bracket on the inside of the large oval or round shields used at the time. Massed troops would unclip and hurl plumbatae as the enemy neared, hopefully stalling their movement and morale by making them clump together and huddle under their shields. With the enemy deprived of rapid movement and their visibility impaired by their own raised shields, the Roman troops were then better placed to exploit the tactical situation. It is unlikely plumbatae were viewed by the Romans as the killing blow, but more as a means of stalling the enemy at ranges greater than previously provided by the heavier and shorter ranged pilum.

Gaul

editThe Gallic cavalry used to hurl several javelin volleys to soften the enemy before a frontal attack. The Gallic cavalry used their javelins in a tactic similar to that of horse archers' Parthian shot. The Gauls knew how to turn on horseback to throw javelins backwards while appearing to retreat.

Iberia

editThe Hispanic cavalry was a light cavalry armed with falcatas and several light javelins. The Cantabri tribes invented a military tactic to maximize the advantages of the combination between horse and javelin. In this tactic the horsemen rode around in circles, toward and away from the enemy, continually hurling javelins. The tactic was usually employed against heavy infantry. The constant movement of the horsemen gave them an advantage against slow infantry and made them hard to target. The maneuver was designed to harass and taunt the enemy forces, disrupting close formations. This was commonly used against enemy infantry, especially the heavily armed and slow moving legions of the Romans. This tactic came to be known as the Cantabrian circle. In the late Republic various auxiliary cavalry completely replaced the Italian cavalry contingents and the Hispanic auxiliary cavalry was considered the best.

Numidia

editThe Numidians were indigenous tribes of northwest Africa. The Numidian cavalry was a light cavalry usually operating as skirmishers. The Numidian horseman was armed with a small shield and several javelins. The Numidians had a reputation as swift horsemen, cunning soldiers and excellent javelin throwers. It is said that Jugurtha, the Numidian king "...took part in the national pursuits of riding, javelin throwing and competed with other young men in running." [Sallust The Jugurthine War: 6]. The Numidian Cavalry served as mercenaries in the Carthaginian Army and played a key role in assisting both Hannibal and Scipio during the Second Punic War.

Middle ages

editNorse

editThere is some literary and archeological evidence that the Norse were familiar with and used the javelin for hunting and warfare, but they commonly used a spear designed for both throwing and thrusting. The Old Norse word for javelin was frakka.[13]

Anglo-Saxons

editThe Anglo-Saxon term for javelin was france.[14] In Anglo-Saxon warfare, soldiers usually formed a shield wall and used heavy weapons like Danish axes, swords and spears. Javelins, including barbed angons, were used as an offensive weapon from behind the shield wall or by warriors who left the protective formation and attacked the enemy as skirmishers.[15] Designed to be difficult to remove from either flesh or wood, the Angon javelin used by Anglo-Saxon warriors was an effective means of disabling an opponent or his shield, thus having the potential to disrupt opposing shield-walls.[16]

Iberia

editThe Almogavars were a class of Aragonese infantrymen armed with a short sword, a shield and two heavy javelins, known as azcona.[17] The equipment resembled that of a Roman legionary and the use of the heavy javelins was much the same.

The Jinetes were Arabic light horsemen armed with several javelins, a sword, and a shield. They were proficient at skirmishing and rapid maneuver, and played an important role in Arabic mounted warfare throughout the Reconquista until the sixteenth century. These units were widespread among the Italian infantrymen of the fifteenth century.[18]

Wales

editThe Welsh, particularly those of North Wales, used the javelin as one of their main weapons. During the Norman and later English invasions, the primary Welsh tactic was to rain javelins on the tired, hungry, and heavily armoured English troops and then retreat into the mountains or woods before the English troops could pursue and attack them. This tactic was very successful, since it demoralized and damaged the English armies while the Welsh ranks suffered little.

Ireland

editThe kern of Ireland used javelins as their main weapon as they accompanied the more heavily armoured galloglass.

Chinese

editVarious kingdoms and dynasties in China have used javelins, such as the iron-headed javelin of the Qing dynasty.[19]

Qi Jiguang's anti-pirate army included javelin throwers with shields.[20]

Modern age

editAfrica

editMany African kingdoms have used the javelin as their main weapon since ancient times. Typical African warfare was based on ritualized stand-off encounters involving throwing javelins without advancing for close combat. In the flag of Eswatini there is a shield and two javelins, which symbolize the protection from the country's enemies.

Zulu

editThe Zulu warriors used a long version of the assegai javelin as their primary weapon. The Zulu legendary leader Shaka initiated military reforms in which a short stabbing spear, with a long, swordlike spearhead named iklwa, had become the Zulu warrior's main weapon and was used as a mêlée weapon. The assegai was not discarded, but was used for an initial missile assault. With the larger shields, introduced by Shaka to the Zulu army, the short spears used as stabbing swords and the opening phase of javelin attack; the Zulu regiments were quite similar to the Roman legion with its Scutum, Gladius and Pilum tactical combination.

Mythology

editNorse mythology

editIn Norse mythology, Odin, the chief god, carried a javelin or spear called Gungnir. It was created by a group of dwarves known as the Sons of Ivaldi who also fashioned the ship of Freyr called Skidbladnir and the golden hair of Sif.[21] It had the property of always finding its mark ("the spear never stopped in its thrust").[22] During the final conflict of Ragnarok between the gods and giants, Odin will use Gungnir to attack the wolf Fenrir before being devoured by him.[23]

During the war (and subsequent alliance) between the Aesir and Vanir at the dawn of time, Odin hurled a javelin over the enemy host[24] which, according to custom, was thought to bring good fortune or victory to the thrower.[25] Odin also wounded himself with a spear while hanging from Yggdrasil, the World Tree, in his ritual quest for knowledge[26] but in neither case is the weapon referred to specifically as Gungnir.

When the god Baldr began to have prophetic dreams of his own death, his mother Frigg extracted an oath from all things in nature not to harm him. However, she neglected the mistletoe, thinking it was too young to make, let alone respect, such a solemn vow. When Loki learned of this weakness, he had a javelin or dart made from one of its branches and tricked Hod, the blind god, into hurling it at Baldr and causing his death.[27]

Lusitanian mythology

editThe god Runesocesius is identified as a "god of the javelin". [citation needed]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Schmitt, U.; Singh, A. P.; Thieme, H.; Friedrich, P.; Hoffmann, P. (2005). "Electron microscopic characterization of cell wall degradation of the 400,000-year-old wooden Schöningen spears". Holz Als Roh- und Werkstoff. 63 (2): 118–122. doi:10.1007/s00107-004-0542-6. S2CID 10774765.

- ^ Punctured Horse Shoulder Blade | The Smithsonian Institution's Human Origins Program

- ^ The Prehistoric Society – Past No. 26

- ^ World's Oldest Spears

- ^ a b Rawlinson, George (1882). History of Ancient Egypt. S. E. Cassino. pp. 474–475.

- ^ "Ancient Egyptian History for Kids: Army and Soldiers". www.ducksters.com. Retrieved 2024-02-22.

- ^ Gosse, A. Bothwell (1915). The Civilization of the Ancient Egyptians. T.C. & E.C. Jack. p. 24.

- ^ Rawlinson, George (1882). History of Ancient Egypt. S. E. Cassino. p. 462.

- ^ Rawlinson, George (1882). History of Ancient Egypt. S. E. Cassino. p. 476.

- ^ Rawlinson, George (1882). History of Ancient Egypt. S. E. Cassino. p. 469.

- ^ "The Guide to the World of Ancient Egyptians". EgyptianDiamond.com. 7 February 2017.

- ^ Connolly, 1998, p. 233.

- ^ Tacitus, Cornelius and J.B. Rives (1999). Germania. Oxford, Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-815050-4.

- ^ Tacitus 1999, p. 40

- ^ Underwood, Richard (1999). Anglo-Saxon Weapons and Warfare. Tempus Publishing. ISBN 0-7524-1910-2.

- ^ The Thegns of Mercia: Weapons

- ^ Echevarría, José María Moreno (1975). Los Almogávares. Rotativa (in Spanish). ISBN 978-8401440663.

- ^ Romanoni, Fabio (January 2020). "Gli obblighi militari nel marchesato di Monferrato ai tempi di Teodoro II". Bollettino Storico- Bibliografico Subalpino.

- ^ "A Chinese javelin head".

- ^ Joseph R. Svinth; Thomas A. Green; Stanley Henning (11 June 2010). Martial Arts of the World: An Encyclopedia of History and Innovation [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 115. ISBN 978-1598842449.

- ^ Faulkes, Anthony, trans. (1995). Edda. pp. 96–97. Everyman's Library. ISBN 0-460-87616-3.

- ^ Faulkes (1995), p. 97.

- ^ Faulkes (1995), p. 54.

- ^ Larrington, Carolyne, trans. (1999). Poetic Edda. p. 7. Oxford World's Classics. ISBN 0-19-283946-2.

- ^ Underwood (1999), p. 26.

- ^ Larrington (1999), p. 34.

- ^ Faulkes (1995), pp. 48–49.

Further reading

edit- Anglim, Simon et al., (2003), Fighting Techniques of the Ancient World (3000 B.C. to 500 A.D.): Equipment, Combat Skills, and Tactics, Thomas Dunne Books.

- Bennett, Matthew et al., (2005), Fighting Techniques of the Medieval World: Equipment, Combat Skills and Tactics, Thomas Dunne Books.

- Connolly, Peter, (2006), Greece and Rome at War, Greenhill Books, 2nd edition.

- Jorgensen, rister et al., (2006), Fighting Techniques of the Early Modern World: Equipment, Combat Skills, and Tactics, Thomas Dunne Books.

- Saunders, J. J., (1972), A History of Medieval Islam, Routledge.

- Warry, John Gibson, (1995), Warfare in the Classical World: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of Weapons, Warriors and Warfare in the Ancient Civilisations of Greece and Rome, University of Oklahoma Press.

- Rawlinson, G., (1882), History of Ancient Egypt, E. Cassino.

- Bothwell Gosse, A. (1915), The Civilization of the Ancient Egyptians, T.C. & E.C. Jack.