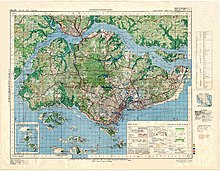

Syonan (Japanese: 昭南, Hepburn: Shōnan, Kunrei-shiki: Syônan), officially Syonan Island (Japanese: 昭南島, Hepburn: Shōnan-tō, Kunrei-shiki: Syônan-tô), was the name for Singapore when it was occupied and ruled by the Empire of Japan, following the fall and surrender of British military forces on 15 February 1942 during World War II.[5][6]

Syonan Island 昭南島 Shōnantō | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1942–1945 | |||||||||||

Anthem:

(English: "His Imperial Majesty's Reign")[1][2] | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

The Empire of Japan at its peak in 1942:

Territory (1870–1895) Acquisitions (1895–1930) Acquisitions (1930–1942) | |||||||||||

| Status | Military occupation | ||||||||||

| Official language and national language | Japanese | ||||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||||

| Religion | State Shinto (de facto)[nb 1] Buddhism Christianity Islam Taoism Hinduism Sikhism (de jure) | ||||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||||

• 1942–1945 | Shōwa | ||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||

• 1942–1944 | Hideki Tojo | ||||||||||

• 1944–1945 | Kuniaki Koiso | ||||||||||

| Historical era | World War II | ||||||||||

• Pacific War begins | 8 December 1941a | ||||||||||

15 February 1942 | |||||||||||

| Nov 1944 – May 1945 | |||||||||||

| 15 August 1945 | |||||||||||

| 4–12 September 1945 | |||||||||||

• Singapore becomes a Crown colony | 1 April 1946 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Japanese-issued dollar | ||||||||||

| Time zone | UTC+9 (TST) | ||||||||||

| Date format | |||||||||||

| Drives on | left | ||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | JP | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | Singapore | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Syonan or Shonan | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japanese name | |||||||

| Kanji | 昭南 | ||||||

| Hiragana | しょうなん | ||||||

| Katakana | ショウナン | ||||||

| Kyūjitai | 昭南 | ||||||

| |||||||

Japanese military forces occupied it after defeating the combined British, Indian, Australian, Malayan and the Straits Settlements garrison in the Battle of Singapore. The occupation was to become a major turning point in the histories of several nations, including those of Japan, Britain, and Singapore. Singapore was renamed Syonan-to, meaning "Light of the South Island" and was also included as part of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere (Japanese: 大東亜共栄圏, Hepburn: Dai Tōa Kyōeiken).[7][8]

Singapore was officially returned to British colonial rule on 12 September 1945, following the formal signing of the surrender at the Municipal Building, currently known as City Hall. After the return of the British, there was growing political sentiments amongst the local populace in tandem with the rise of anti-colonial and nationalist fervor, as many felt that the British were no longer competent with the administration and defence of the crown colony and its inhabitants.[9]

Shortly after the war, the Straits Settlements was dissolved and Singapore became a separate crown colony in 1946. It would go on to achieve self-governance in 1959 and join with Malaya to form Malaysia in 1963, before becoming a sovereign city-state a few years later in 1965. The day of the surrender of the British to the Japanese in 1942 continues to be commemorated in Singapore with Total Defence Day, which is marked annually on 15 February.

Events leading to the occupation

editSingapore was hit by the first Japanese bombs on 8 December 1941. The Japanese forces initially focused on invading Malaya (present-day Peninsular Malaysia), which they captured within 55 days. They captured Johor Bahru by 31 January 1942, with the British forces retreating to Singapore and blowing up the Johor-Singapore Causeway, which linked Singapore to the mainland. Singapore was the foremost British military base and economic port in South–East Asia and had been of great importance to British interwar defence strategy. Singapore was considered so important that Prime Minister Winston Churchill ordered the British Lieutenant-General, Arthur Percival, to fight to the last man. Percival commanded 85,000 Allied troops at Singapore, although many units were under-strength and most units lacked experience. The British outnumbered the Japanese but much of the water for the island was drawn from reservoirs on the mainland.

The Battle of Singapore lasted from 8 to 15 February 1942. On 8 February, the Japanese crossed the Johore Strait by boat and attacked Singapore from the north-west, at the weakest point in the defences. Percival had expected a crossing in the north-east, especially following a Japanese feint at Pulau Ubin the day before, and failed to reinforce the defenders in time. Communication and leadership failures beset the Allies and there were few defensive positions or reserves near the beachhead. The Japanese advance continued and the Allies began to run out of supplies, particularly after the Battle of Bukit Timah from 10 to 12 February and the Battle of Pasir Panjang on 13 February. During the Alexandra Hospital massacre on 14 February, Japanese soldiers killed more than 200 hospital staff and patients. By 15 February, about a million civilians in the city were crammed into the remaining area held by Allied forces, 1 percent of the island. Japanese aircraft continuously bombed the civilian water supply which was expected to fail within days. The Japanese were also almost at the end of their supplies and Yamashita wanted to avoid costly house-to-house fighting.

Japanese General Tomoyuki Yamashita demanded unconditional surrender and on the afternoon of 15 February, Percival capitulated. About 80,000 British, Indian, Australian and local troops became prisoners of war, joining the 50,000 taken in Malaya; many died of neglect, abuse or forced labour. Three days after the British surrender, the Japanese began the Sook Ching purge, killing thousands of civilians. The Japanese held Singapore until the end of the war. Churchill called it the worst disaster in British military history.

Life during the occupation

editTime of mass-terror

editThe main army which took Malaya, the 25th Army, was redeployed to other fronts such as the Philippines and New Guinea shortly after the fall of Singapore. The Kempeitai (the Japanese military police), which was the dominant occupation unit in Singapore, committed numerous atrocities towards the common people. They introduced the system of "Sook Ching", meaning "purging through purification" in Chinese, to get rid of those, especially ethnic Chinese, deemed to be hostile to the Empire of Japan (anti-Japanese elements in the local population). The Sook Ching massacres claimed the lives of between 25,000 and 55,000 ethnic Chinese in Singapore as well as in neighboring Malaya. These victims, mainly males between the ages of 18 and 50, were rounded up and taken to deserted spots and remote locations around the island, such as Changi Beach, Punggol Point, and Siglap, and killed systematically using machine guns and rifles.

Moreover, the Kempeitai established an island-wide network of local informants to help them identify those they suspected as anti-Japanese. These informers were well-paid by the Kempeitai and had no fear of being arrested for their loyalty was not in question to the occupation forces. These informers worked at Kempeitai screening centres where the Japanese attempted to single out anti-Japanese elements for execution. Japanese soldiers and Kempeitai officers patrolled the streets often and all commoners had to bow to them with respect when they passed by. Those who failed to do so would be slapped, punched, beaten and some people would even be taken away to imprisonment or even face execution.

Other changes to life in Singapore

editTo discourage Western influence, which Japan sought to eliminate from the very start of their invasion, the Japanese set up schools and education institutions and pressured the local people to learn their language (Japanese). Textbooks and language guidebooks were printed in Japanese and radios and movies were broadcast and screened in Japanese. Every morning, school-children had to stand facing the direction of Japan (in the case of Singapore, looking northeast) and sing the Japanese national anthem ("Kimigayo"). Japanese propaganda banners and posters also went up all around Singapore, as did many Japanese Rising Sun flags raised and hung across many major buildings.

Scarcity of basic needs

editBasic resources, ranging from food to medication, were scarce during the occupation. The prices of basic necessities increased drastically over the three and a half years due to hyperinflation. For example, the price of rice increased from $5 per 100 catties (about 60 kg or 130 lb) to $5,000 by the end of the occupation between August and September 1945. The Japanese issued ration cards, also known as "Peace Living Certificates",[10] which were very precious to the people at that time, to limit the amount of resources distributed to the civilian population. Adults could purchase 5 kg (11 lb) of rice per month and children received 2 kg (4.4 lb) accordingly. The amount of rice for adults was reduced by 25% as the war progressed, as much of the scarce rice supplies were sent to feed the Japanese military.[11]

The Japanese issued "Banana Money" (so referred to due to the image of a banana tree printed on most of such notes of the currency) as their main currency during the occupation period since British Straits currency became rarer and was subsequently phased out when the Japanese took over in 1942. They instituted elements of a command economy in which there were restrictions on the demand and supply of resources, thus creating a popular black market from which the locals could obtain key scarce resources such as rice, meat, and medicine. The "Banana" currency started to suffer from high inflation and dropped drastically in value because the occupation authorities would simply print more whenever they needed it;[12] consequently on the black market, Straits currency was more widely used.

Food availability and quality decreased greatly. Sweet potatoes, tapiocas and yams became the staple food of most diets of many Singaporeans because they were considerably cheaper than rice and could also be grown fast and easily in backyard gardens. They were then turned into a variety of dishes, as both desserts and all three meals of the day. Such foods helped to fend starvation off, with limited success in terms of nutrients gained, and new ways of consuming sweet potatoes, tapiocas and yams with other products were regularly invented and created to help stave off the monotony. Both the British colonial and Japanese occupation authorities encouraged their local population to grow their own food even if they had the smallest amount of land. The encouragement and production were similar to what occurred with "Victory Gardens" in Western nations (predominantly in Europe) during World War II[13] as food supplies grew ever scarcer. Ipomoea aquatica, which grew relatively easily and flourished relatively well near water sources, became a popular food-crop just as it did the other vegetables.

Education

editAfter taking Singapore, the Japanese established the Shonan Japanese School (昭南日本学園, Shōnan Nihon Gakuen), to educate the Malays, Chinese, Indians, and Eurasians in the Japanese language. Faye Yuan Kleeman, the author of Under an Imperial Sun: Japanese Colonial Literature of Taiwan and the South wrote that it was the most successful of such schools in Southeast Asia.[14] During the occupation, the Japanese had also opened the Shonan First People's School.[15]

Allied attacks

editSingapore was the target of various operations masterminded by Allied forces to disrupt Japanese military activities. On 26 September 1943, an Allied commando unit known as Z Force led by Major Ivan Lyon infiltrated Singapore Harbour and sank or damaged seven Japanese ships comprising over 39,000 long tons (40,000 metric tons). Lyon led another operation, codenamed "Rimau", with the same objective almost a year later and sank three ships. Lyon and 13 of his men were killed fighting the Japanese during this operation. The other 10 men who participated in the operation were captured, charged with espionage in a kangaroo court and subsequently executed.

Lim Bo Seng of Force 136 led another operation, code-named Gustavus, he recruited and trained hundreds of secret agents through intensive military intelligence missions from China and India. He set up the Sino-British guerrilla task force Force 136 in 1942 with Captain John Davis of the Special Operations Executive (SOE). Operation Gustavus was aimed at establishing an espionage network in Malaya and Singapore to gather intelligence about Japanese activities, and thereby aid the British in Operation Zipper – the code name for their plan to take back Singapore from the Japanese. Force 136 was eventually disbanded after the war.

In August 1945, two XE class midget submarines of the Royal Navy took part in Operation Struggle, a plan to infiltrate Singapore Harbour and sabotage the Japanese cruisers Takao and Myōkō using limpet mines. They inflicted heavy damage on Takao, earning Lieutenant Ian Edward Fraser the Victoria Cross. From November 1944 to May 1945, Singapore was subjected to air raids by British and American long-range bomber units.

Naval facilities and docks in Singapore were also bombed on eleven occasions by American air units between November 1944 and May 1945. These attacks caused some damage to their targets but also killed a number of civilians. Most Singaporeans, however, welcomed the raids as they were seen as heralding Singapore's liberation from Japanese rule.

End of the occupation

editOn 6 August 1945, the United States detonated an atomic bomb over the Japanese city of Hiroshima. Sixteen hours later, US President Harry S. Truman called again for Japan's surrender and warned it to "expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth." On 8 August 1945, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan and the next day invaded the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo. Later that day, the United States dropped a second atomic bomb, this time on the Japanese city of Nagasaki. Following those events, Emperor Hirohito intervened and ordered the Supreme Council for the Direction of the War to accept the terms the Allies had set down in the Potsdam Declaration to end the war. After several more days of behind-the-scenes negotiations and a failed coup d'état, Emperor Hirohito gave a recorded radio address across the Empire on 15 August. In the radio address, he announced the surrender of Japan to the Allies.

The surrender ceremony was held on 2 September aboard the United States Navy battleship USS Missouri at which officials from the Japanese government signed the Japanese Instrument of Surrender, thereby ending the hostilities.

On 12 September 1945, a surrender instrument was signed at the Singapore Municipal Building. That was followed by a celebration at the Padang, which included a victory parade. Lord Louis Mountbatten, Supreme Allied Commander of South East Asia Command, came to Singapore to receive the formal surrender of the Japanese forces in the region from General Seishirō Itagaki on behalf of Field Marshal Hisaichi Terauchi. A British military administration, using surrendered Japanese troops as security forces, was formed to govern the island until March 1946.

After the Japanese surrendered, there was a state of instability (anomie) in Singapore, as the British had not yet arrived to take control. The Japanese occupiers had a considerably weakened hold over the populace. There were widespread incidents of looting and revenge killing. Much of the infrastructure had been wrecked, including the harbour facilities and the electricity, water supply and telephone services. It took four or five years for the economy to return to prewar levels. When British troops finally arrived, they were met with cheering and fanfare.

Banana money became worthless after the occupation ended.

Memorials

editTo keep alive the memory of the Japanese occupation and its lessons learned for future generations, the Singapore government erected several memorials with some at the former massacre sites:

Civilian War Memorial

editSpearheaded and managed by the Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce and Industry, the Civilian War Memorial is located in the War Memorial Park at Beach Road. Comprising four white concrete columns, this 61-meter-tall memorial commemorates the civilian dead of all races. It was built after thousands of remains were discovered all over Singapore during the urban redevelopment boom in the early 1960s. The memorial was officially unveiled by Singapore's first prime minister Lee Kuan Yew on the 25th anniversary of the start of the Japanese occupation in 1967.[16] It was constructed with part of the S$50 million 'blood debt' compensation paid by the Japanese government in October 1966.[16] Speaking at the unveiling ceremony, Lee said:

We meet to remember the men and women who were the hapless victims of one of the fires of history... If today we remember these lessons of the past, we strengthen our resolve and determination to make our future more secure then these men and women for whom we mourn would not have died in vain.[16]

On 15 February every year, memorial services (opened to the public) are held at the memorial.

Sook Ching Centre Monument

editThe site of this monument lies within the Hong Lim Complex in Chinatown. The inscription on the monument reads:

The site was one of the temporary registration centres of the Japanese Military Police, the Kempeitai, for screening 'anti-Japanese' Chinese.

On 18 February 1942, three days after the surrender of Singapore, the Kempeitai launched a month-long purge of 'anti-Japanese elements' in an operation named Sook Ching. All Chinese men between 18 and 50 years old, and in some cases women and children, were ordered to report to these temporary registration centers for interrogation and identification by the Kempeitai.

Those who passed the arbitrary screening were released with 'Examined' stamped on their faces, arms or clothes. Others, not so fortunate, were taken to outlying parts of Singapore and executed for alleged anti-Japanese activities. Tens of thousands were estimated to have lost their lives.

For those who were spared, the Sook Ching screening remains one of their worst memories of the Japanese Occupation.

— National Heritage Board.[17]

Changi Beach Massacre Monument

editThe site of this monument is located in Changi Beach Park (near Camp Site 2) in the eastern part of Singapore. The inscription reads:

66 male civilians were killed by Japanese Hojo Kempei (auxiliary military police) firing at the water's edge on this stretch of Changi Beach on 20 February 1942. They were among tens of thousands who lost their lives during the Japanese Sook Ching operation to purge suspected anti-Japanese civilians among Singapore's Chinese population between 18 February and 4 March 1942. Tanah Merah Besar Beach, a few hundred meters south (now part of Singapore Changi Airport runway) was one of the most heavily-used killing grounds where well over a thousand Chinese men and youths lost their lives.

— National Heritage Board.[18]

Punggol Beach Massacre Monument

editThe site of this monument is located off Punggol Road in northeastern Singapore. The inscription on the monument reads:

On 23 February 1942, some 300–400 Chinese civilians were killed along Punggol foreshore by Hojo Kempei (auxiliary military police) firing squad. They were among tens of thousands who lost their lives during the Japanese Sook Ching operation to purge suspected anti-Japanese civilians among Singapore's Chinese population between 18 February and 4 March 1942. The victims who perished along the foreshore were among 1,000 Chinese males rounded up following a house-to-house search of the Chinese community living along Upper Serangoon Road by Japanese soldiers.

— National Heritage Board.[19]

Popular culture

editThe Japanese occupation of Singapore has been depicted in media and popular culture, including films, television series and books:

Books

- The Singapore Grip (1978), a comic-dramatic novel by J.G. Farrell about British merchant families in Singapore and their complicated relationships with each other, other European expats, and other residents, including Chinese immigrants. The novel culminates in the invasion of the Malaysian peninsula and Singapore's occupation by the Japanese and includes several vivid battle scenes written from the point of view of a Japanese soldier in a tank battalion.

- Ovidia Yu's Su Lin series of mysteries, beginning with The Frangipani Tree Mystery (2017), start off in 1930s Singapore and continue into the period of Japanese occupation.

Film

- Leftenan Adnan (2000), a Malaysian film set in the Battle of Singapore

Television series

edit- Early episodes of Tenko, a BBC/ABC production.

- The Heroes (1988), an Australian-British co-production.

- Heroes II: The Return (1991), an Australian miniseries.

- The Last Rhythm (1996), a Chinese language series produced by the Television Corporation of Singapore (TCS).

- The Price of Peace (1997), produced by the TCS.

- A War Diary (2001), produced by MediaCorp.

- In Pursuit of Peace (2001), produced by MediaCorp.

- Changi (2001), produced by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- The Journey: Tumultuous Times (2014), produced by MediaCorp.

- The Forgotten Army - Azaadi Ke Liye (2020), produced by Kabir Khan Films Pvt. Ltd.

List of monuments and historical sites

editSee also

editNotes

edit- ^ Although the Empire of Japan officially had no state religion,[3][4] Shinto played an important part for the Japanese state: As Marius Jansen, states: "The Meiji government had from the first incorporated, and in a sense created, Shinto, and utilized its tales of the divine origin of the ruling house as the core of its ritual addressed to ancestors "of ages past." As the Japanese empire grew the affirmation of a divine mission for the Japanese race was emphasized more strongly. Shinto was imposed on colonial lands in Taiwan and Korea, and public funds were utilized to build and maintain new shrines there. Shinto priests were attached to army units as chaplains, and the cult of war dead, enshrined at the Yasukuni Jinja in Tokyo, took on ever greater proportions as their number grew."(Marius B. Jansen 2002, p. 669)

References

edit- ^ "Explore Japan National Flag and National Anthem". Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ^ "National Symbols". Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ^ Josephson, Jason Ānanda (2012). The Invention of Religion in Japan. University of Chicago Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0226412344.

- ^ Thomas, Jolyon Baraka (2014). Japan's Preoccupation with Religious Freedom (Ph.D.). Princeton University. p. 76.

- ^ Kratoska, Paul H. (1 January 1998). Food Supplies and the Japanese Occupation in South-East Asia. Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 978-1-349-26939-6.

- ^ Lim, Patricia Pui Huen; Wong, Diana (2000). War and Memory in Malaysia and Singapore. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 978-981-230-037-9.

- ^ Abshire, Jean (2011). The History of Singapore. ABC-CLIO. p. 104. ISBN 978-0313377433.

- ^ Giggidy, Kevin; Hack, Karl (2004). Did Singapore Have to Fall?: Churchill and the Impregnable Fortress. Routledge. p. 132. ISBN 0203404408.

- ^ "Singapore – Aftermath of War". countrystudies.us. U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

- ^ "Peace Living Certificate Issued During Japanese Occupation". National Archives of Singapore. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ^ "Japanese Occupation". AsiaOne. Archived from the original on 9 May 2006. Retrieved 1 May 2006.

- ^ "Currency 'Banana Notes' Issued During the Japanese Occupation". Roots.gov.sg. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ "Hungry years". AsiaOne. Archived from the original on 9 May 2006. Retrieved 1 May 2006.

- ^ Kleeman, Faye Yuan. Under an ImSun: Japanese Colonial Literature of Taiwan and the South. University of Hawaii Press, 2003. p. 43 Archived 25 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 978-0824825928. "The most successful was the Japanese school in Singapore. A month after the British surrendered (February 15, 1942), Japan renamed the island Syonan-to (literally "illuminating the south") and founded the famous Shonan Japanese School (Shōnan Nihon Gakuen 昭南日本学園)"

- ^ "A Brief History Archived 2 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine." The Japanese School Singapore. Retrieved on 2 January 2014.

- ^ a b c Lee, "Remembering The Hapless Victims of The Fires of History", pp. 327–329.

- ^ Modder, Ralph (2004). "Sook Ching Registration Centre in Chinatown". The Singapore Chinese Massacre – 18 February to 4 March 1942. Singapore: Horizon Books. p. 72. ISBN 981-05-0388-1.

- ^ Modder, "Changi Beach Massacre", p. 69.

- ^ Modder, "Punggol Beach Massacre", p. 67.

Bibliography

edit- Marius B. Jansen (2002). The Making of Modern Japan. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03910-0.

External links

edit- Fall of Malaya and Singapore, a detailed history of the Battle of Singapore.

- Archive of The Syonan Times. The Syonan Times substituted The Straits Times from 1942 to 1945 under several mastheads.