The IERS Reference Meridian (IRM), also called the International Reference Meridian, is the prime meridian (0° longitude) maintained by the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS). It passes about 5.3 arcseconds east of George Biddell Airy's 1851 transit circle, and thus it differs slightly from the historical Greenwich Meridian. At the latitude of the Royal Observatory, Greenwich the difference is 102 metres (335 ft).[1][2][a]

It is the reference meridian of the Global Positioning System (GPS) operated by the United States Space Force, and of WGS 84 and its two formal versions, the ideal International Terrestrial Reference System (ITRS) and its realization, the International Terrestrial Reference Frame (ITRF).

Location

editThe most important reason for the 5.3 seconds of longitude offset between the IERS Reference Meridian and the Airy transit circle is that the observations with the transit circle were based on the local vertical, while the IERS Reference is a geodetic longitude, that is, the plane of the meridian contains the center of mass of the Earth.[1]

The International Hydrographic Organization adopted an early version of the IRM in 1983 for all nautical charts.[3] It was adopted for air navigation by the International Civil Aviation Organization on 3 March 1989.[4] Tectonic plates slowly move over the surface of Earth, so most countries have adopted for their maps an IRM version fixed relative to their own tectonic plate as it existed at the beginning of a specific year. Examples include the North American Datum 1983 (NAD83), the European Terrestrial Reference Frame 1989 (ETRF89), and the Geocentric Datum of Australia 1994 (GDA94). Versions fixed to a tectonic plate differ from the global version by at most a few centimetres.

The IERS system is not quite fixed to any point attached to the Earth. For example, all points on the European portion of the Eurasian plate, including the Royal Observatory, are moving northeast at about 2.5 cm per year relative to it. The IRM is the weighted average (in the least squares sense) of the reference meridians of the hundreds of ground stations contributing to the IERS network. The network includes GPS stations, satellite laser ranging (SLR) stations, lunar laser ranging (LLR) stations, and the highly accurate very long baseline interferometry (VLBI) stations.[5] All stations' coordinates are adjusted annually to remove net rotation relative to the major tectonic plates. If earth had only two hemispherical plates moving relative to each other around any axis which intersects their centres or their junction, then the longitudes (around any other rotation axis) of any two, diametrically opposite, stations must move in opposite directions by the same amount. The 180th meridian (the meridian at 180° both east and west of the Prime Meridian) is opposite the IERS Reference Meridian and forms a great circle with it dividing the earth into Western Hemisphere and Eastern Hemisphere.

Universal Time is notionally based on the prime meridian.[6] Because of changes in the rate of Earth's rotation, standard international time UTC can differ from the mean observed solar time at noon on the prime meridian by up to 0.9 of a second. Leap seconds are inserted from time to time, to keep UTC close to Earth's angular position relative to the Sun; see mean solar time.

List of places

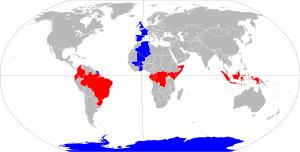

editStarting at the North Pole and heading south to the South Pole, the IERS Reference Meridian passes through eight countries and three oceans (Arctic Ocean, Atlantic Ocean and Southern Ocean):

See also

editReferences

editNotes

editCitations

edit- ^ a b Malys, Stephen; Seago, John H.; Palvis, Nikolaos K.; Seidelmann, P. Kenneth; Kaplan, George H. (1 August 2015). "Why the Greenwich meridian moved". Journal of Geodesy. 89 (12): 1263–1272. Bibcode:2015JGeod..89.1263M. doi:10.1007/s00190-015-0844-y.

- ^ IRM on grounds of Royal Observatory from Google Earth Accessed 30 March 2012

- ^ "A manual on the technical aspects of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea – 1982" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-09-10. Retrieved 2012-03-28. (4.89 MB) Section 2.4.4.

- ^ WGS 84 Implementation Manual Archived 2008-10-03 at the Wayback Machine page i, 1998

- ^ McCarthy, Dennis D.; Petit, Gérard, eds. (2004), "Conventional Terrestrial Reference System and Frame", IERS Conventions (2003) (Technical report), IERS Technical Note, 32, retrieved 2021-07-23

- ^ ITU Radiocommunication Assembly (2002). "Standard-frequency and time-signal emissions" (PDF). International Telecommunication Union. Retrieved 5 February 2022.